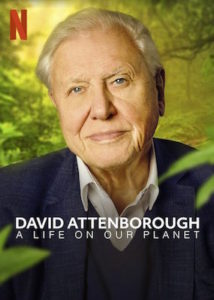

If you have not already watched A Life on Our Planet, serving as a witness statement from Sir David Attenborough, please find a way to do so. During his experience-rich lifetime, Attenborough has had a front row seat to the steady whittling down of nature. Any contemporary nature show will justifiably sound the climate change horn, as A Life on Our Planet does as well. But Sir David digs deeper, as few tend to do, and scoops up the essence of the matter.

I have now watched the show three times. The first instance resonated strongly with recent revelations and writings of my own, and I gladly watched it a second time with my wife. The third time, one hand hovered over the pause button while the other scribbled notes and captured key quotations. This post delivers said quotes and connects them to themes dear to my heart. Note: the quotes in the show are delivered verbally, so any formatting emphasis is my own.

The introduction elegantly frames the story as a tragic loss of wild places, in which we mindlessly eliminate biodiversity and unwittingly dismantle our own life-support machine on this spectacular marvel of a planet. Starting a clock when he was a boy of eleven years, in 1937, key figures are updated during the course of the show. Collected in one place, the figures are as follows:

| Year | Population | CO2 ppm | Wild Spaces |

| 1937 | 2.3 B | 280 | 66% |

| 1954 | 2.7 B | 310 | 64% |

| 1960 | 3.0 B | 315 | 62% |

| 1978 | 4.3 B | 335 | 55% |

| 1997 | 5.9 B | 360 | 46% |

| 2020 | 7.8 B | 415 | 35% |

The 1950s are portrayed as a time of boundless optimism. World War II was over; the middle class was growing and prospering; technologies, innovations, ideas, and conveniences flooded into peoples’ lives. What could humanity not accomplish?

It was toward the end of the 1960s that a sense of limits began to creep into consciousness. Wild spaces are finite and need protecting, it was realized. The iconic blue marble image of Earth from the Apollo 8 excursion around the moon emphasized our vulnerable isolation: a thin shell of life containing all of humanity, save three temporary tourists. To this, he says:

We are ultimately bound by, and reliant upon, the finite natural world about us.

Amen to that, brother. The first four chapters of my new textbook, Energy and Human Ambitions on a Finite Planet, try to make the same case, as do the first two posts of this blog and an early one on space. Shortly after the decade wrapped up, the groundbreaking Limits to Growth work emerged, planting a cautionary flag intoning that the good times can’t last forever. Therefore, some have appreciated what awaits for 50 years.

In the 1970s, we started noticing extinctions taking place right before our eyes. Attenborough makes the point that no one wanted animals to become extinct, but that lack of awareness and a focus on personal benefits obscured the unfolding tragedy. Having largely eliminated or isolated ourselves from predators, achieved control over diseases, and mastered food to order, nothing was left to restrict or stop us.

We would keep consuming the earth until we had used it up.

Whole habitats were starting to disappear. Cutting down forests was seen as a win–win: timber/lumber supplies, and land to use for human development. Sure, when we only think of ourselves in the short term (as markets are geared to do, incidentally), it is easy to see the logic. After detailing a number of crushing losses perpetrated by human expansion, the bombshell quote drops—as obvious as day following night:

We can’t cut down rain forests forever; and anything that we can’t do forever is—by definition—unsustainable.

Immediately on its heels:

If we do things that are unsustainable, the damage accumulates, ultimately to a point where the whole system collapses. No ecosystem—no matter how big—is secure: even one as vast as the ocean.

Such statements should be so self-evident that they do not need saying. Yet, picture humanity looking up, crumbs on all the faces, wearing blank stares; sensing that something important was just said, but not fully grasping it. Back to the donuts. My mental image is of adolescents having found an abandoned mine. They discover great pleasure knocking out the wooden support columns, enjoying their power to alter their environment, and perhaps burning the wood for light and toasty comfort. It’s fun until it isn’t. Those columns serve a vital function. Humans are present on this planet in the context of many functioning, overlapping ecosystems that provide the support structure for our lives. We’re not separate; better than; above it all. Appendix sections D.5 and D.6 in Energy and Human Ambitions on a Finite Planet explore this theme more fully. We’re smart enough and powerful enough to change our environment, but not wise enough not to. This is echoed by Attenborough’s statement:

Our blind assault on the planet has finally come to alter the very fundamentals of the living world.

Be assured that a production of this magnitude has obsessed over every word in the script. The final word choices reflect important awarenesses. “Blind” conveys unwitting. “Assault” conjures a powerful, armed attack. “Finally” communicates that the consequences are becoming apparent at last. “Fundamentals” tries to tune us in to the underlying immutable principles at play. “Living” focuses attention on the true prize of this world—that which distinguishes us from the various other beautiful yet apparently barren hunks of rock and gas hurtling around the vacuum of space.

Having completed his “witness statement,” attesting to the loss of more than half the wild world under his watch, Sir David transitions to describe what may transpire if we fail to develop awareness of our self-imposed peril. He begins with the series of quotes:

The security and stability of the Holocene—our Garden of Eden—will be lost.

We are facing nothing less than the collapse of the living world: the very thing that gave birth to our civilization; the thing we rely upon for every element of the lives we lead.

No one wants this to happen. None of us can afford for it to happen.

My less charitable translation: people don’t mean harm, they’re just being dumb about it. Bless their hearts.

And then the crux of his advice:

It is quite straightforward. It’s been staring us in the face all along [picture a baby orangutan’s face here]. To restore stability to our planet, we must restore its biodiversity: the very thing that we’ve removed. It’s the only way out of this crisis we’ve created. We must re-wild the world.

We will return to this theme in a bit, but in the interim, the presentation lost me for a while—holding up Japan as a model for stabilizing population. But the accompanying visuals were discordant: city-scapes, not natural spaces. Japan, like all developed nations today, depends heavily on profoundly unsustainable practices: from energy requirements to material inputs. How much does Japanese lifestyle depend on a global net of resource collection from previously wild spaces of the world. That’s not our template, folks.

One must endure the obligatory raft of techno-fix solutions that risk communicating: no need to change your expectations and demands; smart people will make it all work out. I suspect this is all in service of the show’s producers insisting that our psyches be soothed and not perturbed too drastically, lest the audience experience yucky feelings of blame or despair. But eventually he pulls out of this chicanery and returns to substantive messaging:

With all these things, there is one overriding principle: nature is our biggest ally and our greatest inspiration. We just have to do what nature has always done. It worked out the secret of life long ago. In this world, a species can only thrive when everything else around it thrives, too.

The word “just” is often a trigger for me—in this case making something that has eluded us for a few centuries seem like a snap. But I agree with the overall sentiment, which is rephrased by asking us to embrace the following reality:

If we take care of nature, nature will take care of us.

This is very similar to how I end the Epilogue in the textbook: Treat nature at least as well as we treat ourselves. He elaborates:

It’s time for our species to stop simply growing: to establish a life on this planet in balance with nature.

It should be a partnership, not an unwitting (note the word “simply,” as in simpletons) exploitation satisfying immediate desires.

Again echoing musings in Appendix sections D.5 and D.6 of the textbook, Attenborough points out that:

As hunter-gatherers, we lived a sustainable life, because that was the only option. All these years later, it is once again the only option. We need to rediscover how to be sustainable—to move from being apart from nature to becoming a part of nature, once again.

I keep harping on Appendix section D.5 in the textbook, because it is incredible how well aligned some of the thinking is. This section explores what ultimate success really means, concluding that the words success and sustainable are essentially interchangeable [see later post on ultimate success]. One will not exist without the other, in the long run.

We’re in the middle of a fireworks show, or a giant party, that looks nothing like “normal” times on this planet and has severely mangled our judgment. It’s a party financed by the one-time inheritance of the planet, unlocked and unleashed by the lubricating effect of fossil fuels. Fossil fuels give us the power to access more fossil fuels, mine deep deposits, and clear forests to make way for precious people and their needs. If we don’t begin to use our power to prepare a successful, sustainable path, the party will end in disgrace and regret—an all too familiar experience for many.

Appendix section D.6 also explores relevant aspects of the evolutionary compatibility of lifestyles far from the sustainable-by-design hunter-gatherer state. Evolution wove an ecosystem web that is essentially founded on sustainability, as unsustainable means unsuccessful and therefore not capable of forming a lasting element of ecosystems. As soon as we began combining our best-in-class intelligence with new stocks of materials that had hitherto not been part of the ecosystem’s balanced equation, we lost the protection of evolution’s built-in near-guarantee of success [see later post on our evolutionary contract]. That’s fine as long as the stocks remain available and are all we need.

But neither are true. The exploited resources are being exhausted, and even aside from that are insufficient on their own to sustain us. We need living, thriving ecosystems for our own survival, yet we hack and burn, knocking out the supports that create a livable space. It’s starting to be less than fun. Let’s stop, yeah, before we cause the roof to come down on our heads.

The final thought in Attenborough’s show, delivered while wandering the ruins of Chernobyl, is:

We’ve come this far because we are the smartest creatures that have ever lived. But to continue, we require more than intelligence: we require wisdom.

This is very much in line with my assessment as well. At this juncture, we have a choice to use our intelligence to “engineer” wisdom: adding a software layer that may not be part of our innate hardware, on the whole. Our guts might say “more for me, please,” but perhaps our heads can intercede to prevent our impulses from getting the better of us.

On the whole, I was deeply impressed by the core messages of this program. It is well aligned with my own conclusions in most places, and dares to look beyond the superficially evident perils of climate change to the deeper foundations of the collision course we have set ourselves upon. Our outsized power as a species bestows on us a grave responsibility to prioritize nature above ourselves, which ironically is the best way to prioritize our own long term happiness on this marvel of a planet.

[See a related post on the core problem of human exceptionalism.]

Hits: 11610

Both you and Attenborough need to start talking about democratically supported policies for rapid population reduction. Everything else is noise.

No doubt this is the mother of all knobs to turn. It is hard for me to imagine a democracy, such as the one I'm in, voluntarily electing a population reduction path. Authoritarian regimes have more luck in this vein.

On the contrary, I recommend looking up Viravaidya's work in Thailand. His TED talks are a good start. I learned of him through Alan Weisman's book Countdown, a great resource.

Here are Family planning success stories https://overpopulation-project.com/family-planning-success-stories.

Population Media Center does great work: https://www.populationmedia.org.

The authoritarian parts of attempts in China and India probably made them less effective, not more.

Meanwhile, many democratic nations promote larger families.

Besides government, one could argue the single most important voice in all our environmental issues is the Pope's.

Agreed, as does everyone, and I recommend starting with learning about Mechai Viravaidya's work in Thailand, and then many other examples of lowering birth rates the opposite of the One Child Policy or eugenics. Voluntary, noncoercive, fun, creating prosperity, stability, and freedom.

Demographic transitions rarely just happen. Individuals and organizations can prompt them. We are not powerless, nor does enabling and facilitating smaller families reduce love, tradition, joy, or freedom.

Waiting for government means waiting forever. Acting to change ourselves can happen here, now, and will enable changing institutions faster and more effectively.

Attenborough said things, but he held back from acting and leading. Not to detract from what he said and he never said he was leading, but there are many things we can do to lead ourselves and others, which is what I'm working on.

It's not true that everyone agrees. I think you underestimate the degree of ecological ignorance and cognitive dissonance pervasive throughout this society. How often have you read commentary stating "Population doesn't matter,only consumption matters " Every country on the planet is absurdly overpopulated, but the average punter doesn't understand how dependent the whole population bubble of this civilisation is on the energy supplied by fossil fuels to keep industrial agriculture functioning. And the 'fixed' nitrogen supplied by the Haber-Bosch process essential to keeping that population bubble fed. The resultant eutrophication of lakes and rivers, nitrate pollution of aquifers,vast ocean dead zones, nitrous oxides increasing climate disruption are the price we pay, but most people don't understand Earth System science.

Wow David, I appreciate your message. Yes, most people seem unaware of our global predicament. Governments are run by corporations who are led by rich corporate sociopaths, who really don't care about anything other than themselves in the present.

I believe we are long beyond fixing the destructive direction the human race is going. I think it may be a matter of a handful of years before our consumptive ways come to an end. I hope I'm wrong, but fear I'm not.

That's a common view, but population growth is not to blame because the regions which are still growing are using very little resources compared to richer areas where population growth has ceased. And focusing on it can get in the way of making the changes needed.

The average number of children per woman is now 2, i.e. the replacement level. The most that population control could achieve is to reduce this to zero, but that would only reduce the world population by 12% in 10 years. Yet 10 years is how long we have to cut our emissions by more than 50% if we are to stay within the 1.5C budget. Clearly, given the urgency of the situation, population control is not going to be the main tool. Unless, by population control you're talking about a cull of the wealthiest 10%, which really would cut emissions by half. Personally, I prefer the option of changing consumption patterns, and doing this at the systemic level.

Incidently Rob, Sir David is actually talking about population control – he's a patron of Population Matters. However, he didn't include it this documentary as the main driver of the destruction of the natural world he was documenting is the increased per capita consumption in rich countries.

"sustainable-by-design" sounds like a romanticization of hunter-gatherers. The transition from the Paleolithic to Mesolithic seems driven by having hunted out the big game population. H-G advents to Australia and the Americas are correlated with megafauna extinctions that seem hard to pin on climate change alone. The shift through increasing horticulture into agriculture was probably driven by the old ways not working as well (likely because of climate change) not because someone invented agriculture and thought it would be awesome.

I wonder about the definition of 'wild space', too. Hunter-gatherers can manage their environment too, often by burning. A lot of what might be called "wild" in the Americas would be more accurately called "formerly managed by Indians who got wiped out by diseases", possibly including the Amazon rainforest which strikes some researchers as an abandoned orchard.

Sir David has lived a charmed life and given his numerous excursions, he has thankfully and most fortuitously documented for our education and indeed our entertainment, many, if not all of life's richly diverse habitats.

To circumnavigate the globe even once would be a rewarding experience but to have done so on numerous occasions and as many perhaps to have even lost count of, one can only presume to know what that must feel like.

I would give anything to have traveled 1/1000 along the journey that he has been on and would note that I've traveled considerably less even than my wildest dreams would allow, constrained as I have been, when lacking the wherewithal to do so. My inclination however is to practice what I am told and attempt to follow most diligently an ethical path, how bold of me. Our world has many anomalies and contradictions abound, similarly there are hypocrites too, take your pick.

I agree that the main part of the film was compelling, but I was utterly disturbed by the lack of analysis of the drivers of development, apart from overpopulation. This is also reflected in shortcomings of the much shorter and optimistic second part of the film, which I considered misguided, and full of errors. I expand on that in my own review: https://gardenearth.blogspot.com/2020/10/a-life-on-our-planet-review.html

I think I am so accustomed to being let down by the messaging in shows of this sort—which can't seem to look past climate change and end in glorious expressions of hope—that this one stood out as special. Identifying root causes (consumption; separation from nature) and making the radical suggestion that we re-wild the planet puts it in a new class. It's not the documentary I would have made, but while most score a 1 or 2 on a scale of 10, A Life on Our Planet leaps well ahead of the pack and might even get a 5 or 6 in my book, which is noteworthy and deserves some praise.

I wonder if I could ask you to do "Do the Math" on Morocco please. I was very troubled by his segment on solutions especially renewables in Morocco. He says that Morocco now gets 40% of its energy "needs" from renewables – and we are left in no doubt that solar is playing a big role in that.

However I can't see anything like that in the stats – the BP statistical review has 2019 numbers that seem to show about 7% energy consumed in Morocco came from renewables . The IEA shows about 3% of energy in 2018 came from wind/solar/hydro – although oddly it has about 6% coming from Biofuels and Waste. I can see that as of 2020 Morocco has about 40% of installed renewable power "capacity" – about a third of which is solar operating at around 20% capacity factor.

So it seems to me that this is classic example of mixing up energy/power and capacity/generation with creative exaggeration of the role of solar to date. Don't get me wrong, solar in Morocco probably makes sense (unlike here in the UK) – but Attenborough (and his researchers) have a responsibility to get the facts straight – this is going out to an audience of millions.

They also ignore the bigger picture that the growth of total energy consumption in Morocco outstrips any incremental gain from renewables i.e. their consumption of fossil fuels is increasing – which is reflected on a global scale

I am no expert – just a Googler. Am I missing something ? Is this not another glaring example of Bright Green Lies ?