We are accustomed to a left–right political spectrum. But said spectrum is only a tiny corner of the whole space of possibilities, even though practically everyone you know is wedged into it. Similarly, we use the word “light” to implicitly mean the narrow range of radiant energy that’s visible to human eyes, despite its being only a thin sliver of the full electromagnetic spectrum. All modern political schools share and support the context of an aberrant, exploitative modernity, making them real “birds of a feather.”

One window into political leanings is to elucidate an honest assessment of what one cherishes the most. But be careful about taking at face-value what people say they care most about. Sometimes they might even fool themselves. Below is a list whose scope (number of beneficiaries) increases as one moves down, and which might imperfectly map onto political leanings.

- Self/Ego

- Power

- Corporations

- Market economy

- Small businesses

- Families

- Welfare of all people

That’s usually where it stops, in terms of scope. Some might also care for the environment, but only insofar as people have access to clean air, water, food, and don’t suffer health maladies from pollution. The first item on the list doesn’t map cleanly onto left–right (no shortage of self-centered leftists!), but belonged on a list of what people care most about. One form that self-prioritization can take is personal salvation in a religious context.

Megalomaniacs, dictators, oligarchs, and authoritarians populate the top of the scale. Fascists also lean toward that upper end, as do—I would say—many MAGA Republicans in the U.S. Traditional Republicans occupy more of the middle range, while Democrats tilt toward the lower end. Marxists might be said to be all the way down. Yet, the demarcations are not clean, allowing funky mixtures. The overwhelming majority of political parties, for instance, work to support a vibrant market economy.

Ralph Nader ran for president of the U.S. in 2000, far enough to the left of George W. Bush and Al Gore that he characterized the two as “Tweedledum and Tweedledee”—implying a nearly inseparable twinness to the two. From far enough away, that’s what it looks like. A radical leftist or rightist will see all establishment politicians as muddled enablers of a dysfunctional system.

Where do I fall on this spectrum—or am I even on it? I’m going to make you wait for a short bit.

We might also try assigning percentages, crudely, to the groups above. If the primary cherished unit is oneself, one out of 8 billion people is the “top” 0.00000001%. Numero uno! Corporations—the wealthy and powerful—might represent the top 1%. By the time we progress down the list to all people, we might say it’s 100%. End of story, right?

Not for me. Despite a dangerously swollen population and depleted wildlife, humans are only 3% of animal biomass, 0.01% of living mass, perhaps one ten-millionth of species, and well-less than 0.000000001% (one-billionth) of the living medium (atmosphere, soils, ocean) on the surface of Earth. It gets staggeringly smaller if considering the entire Earth (required for sufficient gravity to hold an atmosphere) or the sun (the energy source for life), and so on.

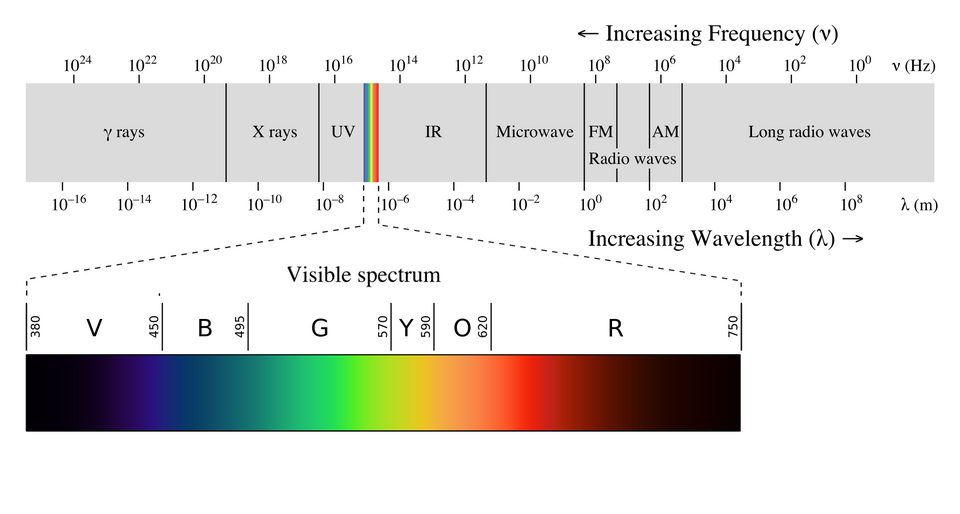

By these measures, the 100% human focus of even the hard-over Marxist puts them into ultra-elite status: into a tiny corner of the room. And that essentially guides where I landed. On this spectrum model—incomplete and flawed as it is—I might call Hitler and Marx Tweedledum and Tweedledee: both parts of the visible spectrum. Don’t get me wrong: it’s not that I cannot discern a difference between red and blue, or that I would have equal preference for spending time with either Marx or Hitler. But both were committed human supremacists, which I find to be ugly. Neither questioned the trajectory of modernity: they wanted more of it, but parceling out the loot differently—among humans, of course. Both sought to perfect the production of goods and services for the benefit of their differently-scoped constituents—through exploitation of “resources”—with no regard for the ecological toll insofar as humans (of Taker culture) get what they want in the short term. Workers of the world, unite?

Just imagine asking an isolated hunter-gatherer whether the societies envisioned by Marx or Hitler seemed more similar or more different. From that very different way of living, surely the two would be nearly indistinguishable. Both involve money, manufacturing, mechanization, copious energy, and all those elements wholly familiar to us and wholly alien to other (legitimate; time-tested) ways of living.

In this framing, I am so far left that the left doesn’t recognize me as “left.” It comes back to what one cherishes and thus favors. To the right fringe, the traditional conservative Republican seems soft and leftish, and even punitive toward the powerful by their support for any regulations at all (food safety, air quality). To the Republican, the Democrats’ focus on equity among all people can seem punitive toward businesses: the real pillars of a functioning modern society. Many traditionally-privileged white straight males feel discriminated against by the “woke” left. To a leftist cherishing all people above everything else, my focus on the more-than-human world comes off as punitive toward humans (of modernity): “unfair” restrictions and disfavor for the most privileged (and abusive) culture on the planet. Because I view our modern culture as a Human Reich, I can’t help but ask: how does one even approach prioritizing welfare for members of a culture complicit in ecocide? True fairness does not always work in our favor, as we rig things to go.

This is what I mean when I say that I can be so far left as to not seem “left” to a leftist. Because I don’t prioritize issues of equity among humans, I might be wrongly cast into the anti-DEI (diversity, equity, inclusion) camps of the right. But that would be completely inaccurate.

To be clear, I would not call myself anti-DEI. I totally buy the validity of the points, within the narrow context of human-only considerations in an anomalous time of profligate abundance (made possible by a multitude of shameful exploitations). Genuine, unjustifiable barriers exist to under-represented groups. I’m on board with identifying and dismantling these barriers—much as I am on board with improving access to healthy food in inner cities. It’s just not close to my top priority, as few humans or animals on the planet will have access to healthy food if ecological (more-than-human) priorities continue to be ignored—and cities won’t remain viable for very long anyway, so there’s no “getting them right.”

I’m more concerned with the course and speed of the Titanic (or why there even is a Titanic) than with the proper arrangement of deck chairs. Of course I would much prefer an orderly arrangement of deck chairs rather than a trip-hazard jumble: in the narrower fantasy that they also remain dry and well above sea level. As in Ishmael Chapter 12, my chief aim is not fairness and equity within the prison, but in dismantling the prison altogether—arguing that we oughtn’t be on the Titanic in the first place.

Being so far from the mainstream, how do I know that I’m far to the left of “left” and not far to the right of “right?” That’s pretty easy, because the left–right distribution can be crudely mapped onto preference for egalitarian arrangements vs. tolerance of hierarchy. My guiding principle is that humans evolved in small tight-knit groups of basically egalitarian people. These successful cultures tend to be very light on power structures and division of labor. In fact, many follow deliberate practices tuned to tamp down power concentration. In those cultures that recognize a leader, the leader does not exert power so much as make sacrifices for the team and offer valued opinions on appropriate actions.

The opposite of hierarchy is, in some sense, anarchy: lack of archy—where the “arch” root means “rule.” Anarchy has a bad rap for the legitimate reason that it’s a terrible, non-viable way to structure modernity. But I would say modernity is no way to structure ecologically-suitable living. Anarchy works exquisitely well in the community of life. It’s hard to exert power over people who can take care of themselves (including their own access to food).

It’s funny that the political left and right both argue endlessly and unproductively about rights (for corporations, humans, blastocysts), but I’m so far left that I see “rights” as fictional constructs of “the right” (which includes Marxists for me). Rights are not facts of the universe—thus the inevitable, unresolvable squabbling—but unfounded claims that we might wish to be true geared toward giving us things we want.

Part of the fantasy is that if we just adopt the correct political perspective, tune our laws, and dial in our systems, we’ll finally achieve the paradise we deserve—as the irrelevant, obsolete community of life cracks up and disintegrates. Ecological and biophysical considerations over appropriate timescales are typically wholly absent from such musings, instantly invalidating them as viable paths.

So, whether we’re talking about Karl Marx, Ayn Rand, Noam Chomsky, or Milton Friedman, they all look strikingly similar from my vantage in the hinterlands. All champion anthropocentric systems doomed to fail by ecological standards on biophysical grounds on the timescales that really count.

Views: 6520

Murray Bookchin developed a body of theory about "social ecology", which recognises the fundamental importance of organising society to live within planetary limits.

Brief overview here: https://theanarchistlibrary.org/library/murray-bookchin-what-is-social-ecology

The Kurdish leader Abdullah Ocalan has further developed Bookchin's ideas into "democratic confederalism", which places ecology & women's rights at the centre. The people of the Democratic Autonomous Administration of North & East Syria (DAANES, also known as Rojava) have put this into practice since 2010 and the Zapatistas in Chiapas, Mexico, follow similar methods, all rooted in direct democracy mediated through peoples' assemblies.

https://democraticmodernity.com/the-main-principles-of-democratic-confederalism/

I can't disagree with one word of this article. It 'rings true' – because it is the truth.

The terms 'left' and 'right' are obsolete. If they ever meant anything, it's now clear that they only serve to divide people into artificial, rival factions, existing *within* the ****show that is modernity. This division is beneficial to the rulers/oligarchs who accrue most of the wealth extracted from Nature by the working/consuming masses.

Most are oblivious to the fact that they owe their comfortable living to this rotten system. They wouldn't last too long without it, domesticated and de-skilled as they are, watching the adverts, believing the hype, buying the smartphones, EVs etc etc.

The elephant in the room, that the modern world is bound to fail, is still taboo among all politicians – as it must be. No one's getting votes by telling it how it is, regarding human supremacism etc etc. (Then again, voting only legitimises and prolongs the system.)

So scrub 'left'/'right'. Let's just have reality.

Thanks, this helps elucidate my own political intuition which I have struggled to describe. I've previously tried to explain to people that I'm not on the political spectrum, or that I'm politically post-tragic. Left of left because of non-strict hierarchies in Dunbar number tribes is an interesting take. – I've come to believe that this is simply our evolutionary ecological niche, and every empire-building exercise is some hubristic version of 'we know better', and despite hundreds of failures throughout the Holocene (and current failure in progress), we've yet to lose our hubris. The Latin term for wooden-headed dullards might have been a more accurate description of our species than 'homo sapiens'.

Back to politics, when there is no such a thing as a non-humanocentric ecologically sensible political movement, I find myself scratching my head when the argument seems to be that 'omnicide is okay as long as our political sports team is the one committing it', or, 'we're the business as usual good-guys because we're wearing this or that color shirt'.

The right solves problems in the easiest possible way, by denying they exist (endless fossil fuels, climate change is a hoax). The left offers useless platitudes and green-washed techno-hopium industrial products as if we can have our cake and eat it too, economically growing our way out of the problems cancerous economic growth is causing. Just don't pay attention to the top that was cut off of that mountain, or the diesel used in mining, or the mining tailings poisoning that river and lake, or that forest that was cut down to build a road to get to the mine, or the dependence on fossil fuel infrastructure and six continent supply chains, or the coal used in the high heat process to make that solar panel, or the styrofoam it's wrapped in that will last a million years, or the big truck running on diesel that delivered it to your house, or the toxic chemicals and rare earth minerals that will pollute the environment later when it breaks down, or the fact that we're the only species on the planet using exosomatic electricity (and only for a sliver of our species' existence on this planet, suggesting that we were previously fine without). These industrial products are 'green', just shut off your brain and listen and it will all make sense… – Delusions on a continuum.

It's only disconcerting to me how few seem to see through what ought to be obvious. Yet I find myself commonly ostracized for suggesting that featherless bipeds try to rub two brain cells together every once and awhile (or maybe it's my charming personality).

Try to remember that nature really is "red in tooth and claw". Much of the construct of human society is an effort to mitigate the associated misery. It should be no surprise that the result is always tragic in multiple ways.

I often walk on the country road that I live on and it always reminds me that every lovely plant or creature that I see is working as hard as it can to accumulate as much energy as possible regardless of the harm caused to those in it's environs. Humans are just better at damaging the biology around us but no less caring than the other creatures.

@Joseph Housman

Respectfully, not so! – if I may…

Just take the forest as an example. The upper canopy provides shade so the soil can retain moisture for the understory to flourish. The squirrel plants oak trees by burying acorns for later and then forgetting about some of its cashes. The beaver shares its home with other species in different compartments, and its dam creates a wetland that countless other species benefit from. I could go on.

Though you might say: – "Well, yes, but they don't really do this on purpose." Then, how about a crowd of people? When they begin moving randomly in one direction and everybody somehow follows there. Is that on purpose? The way I see it, what we call common goal-seeking here is actually the property of any complex enough dynamical system; mechanical or living, no matter. It just happens to be that the apparent object of ecosystems' common goal is to survive TOGETHER. The fact that we are here proves this better than anything. But. Self-organization is also a matter of some minimum requisite variety, which you could say is species diversity for the living world, us included. When that minimum is breached, self-organization collapses, and with it the common goal-seeking behavior. We seem to be trying our hardest to so push the boundaries as to test where that limit is.

But there might be just a teeny-tiny problem with that method: this particular limit we may only see in the rear-view mirror. Each inadvertently collapsed ecosystem is a sad testament to this. Think the large and increasing patches of marine dead zones around coastal areas and some at open seas, where nothing breathing can live any more.

Well put. I also cringed at the resurrection of the "tooth and claw" trope, so am glad you raised a coherent objection. Teeth and claws do exist, and do get red with blood, but let's not have that narrow fact become the guiding principle for what living is all about.

The mistake is thinking of species as being isolated in a scary world, competing for its survival, and surviving only via defeat of similarly selfish competitors. No one would have made it this far in that brutal setting. Cooperation and mutualism—even if not cognitively established—emerges because it works. An example close to home is gut microbiome. When did we *decide* to establish that symbiosis, exactly? Obviously, we never did and only recently became aware of it, even. If, based on philosophical objections, we decided to eliminate our gut microbiomes (win) we would find ourselves in a sorry state (losers).

"Try to remember that nature really is 'red in tooth and claw'."

Howard Odum had a lot to say about that.

It's true that we all dissipate trophic energy in order to live. Feedlot cattle pens seem to be particularly "red in tooth and claw" to me.

But in low-energy biomes, cooperation seems to predominate, whereas high-energy biomes foster competition.

All modern humans have known have been high-energy situations, either by (as Catton would have said) "take over" or by "draw down".

We're about to enter unknown terrain, as fossil sunlight goes into permanent, irrevocable decline. Will we become more cooperative, like we did in the Great Depression, when people down on their luck tended to share more?

There's a book titled _The Arrogance of Humanism_ by David Ehrenfeld. Ehrenfeld's "humanism" includes "secular humanism," but it includes, as well, secular humanism's fundamentalist antagonists. It also encompasses science that is done with the implicit motive that humanity's needs are the measure of all things.

And I'm reminded of something the great physicist Richard Feynman said in one of his 1962 Messenger lectures at Cornell (videos available online). His overall topic was "The Character of Physical Law." At the end of the second lecture, which had been about the relationship of mathematics and physics, he finished by telling his lay audience how difficult it was to convey notions of the deepest beauty of nature (i.e. mathematical statements of fundamental laws) to people who had limited training in mathematics. It was like describing music to the deaf. He thought C.P. Snow's "two cultures" coincided with the division between those who had and those who had not studied enough mathematics to comprehend nature "on her own terms." Of the latter group he concluded, "Perhaps it is because they are limited in this way that some people are able to imagine that the center of the universe is man."

Thank you for this comment.

Tom,

I’ve been thinking about this left right spectrum as well and landed similarly to yourself – way outside it. (In theory at least)

If you create a ‘plot’ with sustainability for the y axis and radicalisation on the x axis we can place the left right spectrum on it. It would sit low on the y axis and fairly far along the x axis starting with the left wing, then progressing further to the right towards right wing and even more extreme – the Hitler zone. Leavers would sit very high, we could say at the very top of the y axis, but very close to the x origin – i.e. unradicalised and sustainable (proven). The plot would be very non linear with a fracture between the two groups as they are fundamentally different. It is also possible to estimate ranges for various economic and political systems. Where does capitalism fit, what about communism? This would show them as birds of a feather, not so different. It also demonstrates that the whole radicalised shit show is bundled low on the sustainability front. It is all a bit subjective but opens the overton window on the limited left right perspective.

Tom, was it you or someone else that said that today’s political spectrum may as well be curled around and made into a circle, because if you go far enough left or right the two become more similar than different? I don’t know if this is just compete nonsense, but it would certainly emphasise the idea that politics that is built upon a foundation of the “world belonging to us” condemns us to imprisonment within a very limited section of “mind space”, and that efforts to escape this space through movement on the spectrum are futile.

I don't think that was me. I mean, sometimes extremes agree on funky issues: libertarians and leftist hippies don't want drugs to be illegal, for instance. The left fringe can be anti-vax, just like MAGA Americans. Strange bedfellows. But extreme egalitarianism won't circle around to join up with authoritarian, which is one of the main left–right axis descriptors.

What you are describing is called "horseshoe theory" and it is nonsense.

The right care only about the self, the left consider the group. The two views are irreconcilable.

True. I guess the image of a circle is again another example of people trying to create a simple model for something that is complex and messy 🙂

By the intermediate value theorem, the the populous on the right of the 'mainstream' left, must be moved through there in order to reach the left of left that cares about the non-human world. In other words, "please still vote for your left of center party that stands a chance!"

So far left of left it all looks like late stage Modernity from where I am, just ‘weird scenes inside the gold mine’, all sides of human political spectrum enthusiastically encouraging economic growth which is devouring destroying all life on earth

All hail our gods, cheap gas and cheeseburgers! on the signpost up ahead: The Road…

A late but great scientist’s salvo fired into the self absorbed face of human supremacy is retired career federal conservation biologist Lyle Lewis’s book, Racing to Extinction: Why humanity will soon vanish.

I’m still fighting on automatic to protect and restore the few wild forest patches I can but at best hoping to lifeboat these few diminished ecosystems into a post collapse human free planet

Thanks Tom for all your work we lean on you heavily for strength

I find myself thinking about these issues at a basic level, even though I might "feel" something completely different. Though I'd consider myself in a similar position to you, surely all organisms (or almost all organisms) prioritise the self before anything else? Isn't that what evolution works on? If the self doesn't survive and reproduce, its genes don't get propagated to infuse the population. In a life or death situation, the one who prioritises the other person doesn't survive to pass on those apparently altruistic genes.

The left to right spectrum is all about human societies. I think I'm over human societies (though I can't help but have opinions about the aspects of them) but I sure as hell want to survive and be comfortable in this human society, whilst recognising the environmentally destructive nature of it.

While certainly there's some truth to the self-focus model, be aware that our culture has hammered this "survival of the fittest" competitive narrative into our heads—compatible as it is with a capitalist market system. If Life were all solo performances, never depending on others or expressing mutuality, then the selfish model might apply—if Life were scattered elements rather then a WEB. Tribal lifestyles stressed health of the group over the individual (the individual had no hope of health if the group was not in good shape), and had explicit practices to look after the health of the community of life they depended on. They knew they were supported by a web. So, don't swallow whole our mythological slant on evolution.

I would just add that one of the advantages we human have developed is that we can look after eachother when we get sick and nurse people back to good health.

Without this ability we would all have perish.

Chimpanzees also do this.

https://www.frontiersin.org/news/2025/05/14/chimpanzees-medicinal-leaves-first-aid-frontiers-ecology-evolution

@Mike Roberts.

Thanks for that. Very interesting 👍

As you mentioned, the health of the group benefits the health of the individual. However you cut it, surely it's the individual that matters most to that individual, even if he/she may feel like they are altruistic.

Why is it mythological to accept that, for evolution to act, the individual must reproduce?

Hrmmm….

who is this I you keep referring too?

Aren't you just a bag of interacting chemicals with a bad case of neural flatulence?

a mindless, soulless, thing with no free will?

I am just trying to square your philosophy with your actions.

Because it seems like you are acting like you actually have a mind and free will and that other do as well. because other wise your actions make no sense.

Exactly: language develops as a cultural construct, loaded with implicit interpretation. Thus, to be understood, this bag of atoms must resort to language of "I" and "me" as if some separate mind/soul is in the driver's seat. It's irksome.

So, yes: mindless, soulless, and lacking free will sounds correct! Yet no less amazing and capable of cognition, decisions, action. Lack of mind is not at *all* the same as inert and incapable of coordinated action. How dismal and nihilistic and unimaginative and narrow to believe so!

When thoroughly biased by such fantasies as mind/soul/free-will, it is basically impossible to understand any other context for actions: a rookie mistake that is remarkably prevalent. Squaring isn't hard once free of those shackles. The squaring exercise is thus really up to the "believer," but also nearly impossible. Watch this space for a post coming soon called What is Life, but it closely parallels an earlier one called Decisions, Decisions. This attempts to guide the "squaring," but admittedly it's a heavy lift from inside the box.

There is a word, "decision," which has a dictionary definition something like, "a determination arrived at after consideration." But there is no consideration other than neurons firing in some sequence determined by the development of the brain. Of course, that development continues throughout a lifetime and can be altered by environment and even information. But when one knows that there is no free will, it's hard to think of it as a decision.

Who or what is "capable of cognition, decisions" then, if there is no 'you'?

Are animals capable of reason, or do you agree with Mike Roberts that "there is no consideration other than neurons firing in some sequence determined by the development of the brain"?

It seems to me that you are trying to have it both ways – i.e. you want to allow animals to have agency, while simultaneously describing them as "mindless" and "lacking free will".

It's ok to admit you made a mistake.

I know this line of thinking is uncomfortable/disagreeable to many. It's fine to use a label to describe a particular package/organism that indeed is its own unique set of exquisitely-arranged atoms. The problem is one of interpretation, wherein culturally we are unwittingly trained to believe the "I" refers to something grander; transcendent: some "owner" in charge of the stupid corporeal dreck.

For the middle paragraph: no need to make a distinction (forcing one is where the problem lies): reasoning/cognition happens by neurons—arranged not randomly but by genetic and environmental influence/feedback to operate adaptive;y/functionally. So yes, "my" (no actual non-corporeal owner) brain can neurologically process inputs, apply logic, and all the rest—which I don't want to dismiss: it's amazing. All animals with brains have similar capabilities, to various degrees. Living organisms without a single neuron also process stimuli and react in adaptive ways (shaped by feedback: those who can't don't survive). But we go way out on an unsupported limb to posit anything other than that every scrap of it traces to material interactions. One could label this a misfire of our hardware: arriving at spurious conclusions, which of course happens *all* the time.

So yes: both can be true (can have it both ways): Life has agency—able to react in complex ways to complex sets of stimuli in ways that on average confer adaptive benefit or it would not have survived—while still being the direct result of material arrangements and nothing else. There's nothing fundamentally wrong or impossible about that view. It's just extremely distasteful to our culture, and at odds with the convincing illusion. In fact, it's the simplest explanation, however unpalatable. Evidence abounds: tamper with the material arrangements and agency goes away pronto! Not a single piece of evidence to the contrary: that agency is somehow detached/independent (not simply emergent) from the material. So that part seems to be the domain of wishful thinking.

Robert Sapolsky also argues that we don't actually make choices. But we also deeply _perceive_ ourselves as choice-makers, and do so in a way that's also hard-wired into us. So, we're the most deluded of all species, but also the one with the most open developmental avenues and the most incentives to try them. Could one of those avenues reconcile our own maximum collective (Benthamite) happiness with actual sustainability? Maybe? (And isn't trans-leftism — a blend of the narrow and the wide perspectives, in your terms — the only possible way to find out?)

A question for whoever here wishes to answer it:

Is your belief in materialism determined by unconscious processes in your brain, or by reason and evidence? If you came to your belief by reason, then you have disproved your own argument.

Nice try at a "gotcha." Paradoxes are almost always the result of missing context or artificial distinctions. In this case, evidence–reason is a form of stimulus–response. Neurons process inputs (impressively complex, to be sure) and arrive at conclusions. It's precisely what brains were evolved to do—useful in a diversity of contexts. There's no fundamental problem or disconnect: brains are compelled to reach the conclusions they do based on their structure (wiring) and inputs—which include inputs from millions of years ago (in shaping brains) right up until the second before. It could not have been helped, but that does not mean the process did not heavily rely on cognition via neurons.

I'll add a bonus, triggered by your use of "unconscious" in the question. Maybe it's *awareness* of the cognitive process that makes it seem directed or controlled or whatever. That can be explained by the wiring of the prefrontal cortex: specifically constructed to connect to many parts of the brain to weigh the various (sometimes competing) processes as a cute trick to select outcomes. It's a layering: one part of neural hardware amplifying or inhibiting others in a way that (on average) confers adaptive benefit. It is in this part of the brain that the brain's awareness of its own operation arises. To me, the fact that a prefrontal cortex is wired into the reasoning process does not change the fundamentals: just adds delightful nuance, layers, complexity.

You say "That [the cognitive process seems directed] can be explained by the wiring of the prefrontal cortex", this being "one part of neural hardware". Such language ('wiring', 'hardware' etc) likening the brain to a computer is typical of the prevailing scientific view (which itself informs the wider culture of modernity).

Your thoughts (or 'cognitive processes') *are* directed by you. The arguments you put foward here are unlikely to 'confer adaptive benefit' – but why should they? The idea of exchanges like these is not to ensure our genetitic longevity but to establish truth.

Iain McGilchrist again: "[If] you ask biologists explicitly, they will, with a few exceptions, cleave to the machine model; but when you listen to what they are saying, implicitly they abjure it. Yet despite this manifest dissonance at the core of biology today, the machine model is the one that is peddled to children, students, and the general public wishing to learn more about biology, the fascinating study of the nature of life. Any suggestion otherwise is pounced on as evidence of heresy and denounced."

From 'The Matter With Things', the follow up to 'The Master and His Emissary' (I confess to having read neither, but I'm going to read TMWT. It seems like it would clarify some of the points I'm trying to make).

"a prefrontal cortex is wired into the reasoning process"

But reasoning cannot be done by machines. It can *only* be done by living things. Therefore, there is some fundamental difference – over and above complexity – between 'life' and 'mechanism'. Only life can have experience/knowledge/awareness etc etc.

I.e., living things are categorically different to machines. They feel, they decide, they choose.

Which makes the ongoing commodification and destruction of the Natural world – the *feeling* world – all the more obscene.

The perpetual confusion—which admittedly is likely insurmountable given limited cognitive capacity and a deeply ingrained "sense" of being—is that machine comparisons to life are manifestly invalid because (paraphrasing): just look at the differences in capability! I mean come on! It's obvious right? No one would confuse a computer for a flesh-and-blood living being, so there *must* be a categorical difference and a fundamentally different operating principle, divorced from a purely material plane, right? I mean, I can't personally connect all the dots, so they are not connectable in theory, even.

I can easily forgive a person for not buying the material explanation on the grounds that it's too hard for any of us to connect all the dots in a tidy, fully-described story going all the way from electrons to love. I get it. It requires some letting go, which is also hard.

I can also wholly agree that any machine we contrive (in mere millennia of practice) is painfully, woefully, excruciatingly simplistic, dumb, and limited compared to what Life has cooked up over billions of years by applying feedback to material constructions. It's just that the vastness of the gulf does not constitute a legitimate categorical, ontological gap. Too huge to fit snugly in our brains? Sure, but why should that arrogant requirement be the criterion? Will we ever build artificial machines that rival what life can do? I seriously doubt it: we're not remotely so capable.

Yet, life is unambiguously made of matter, and does all its fabulous tricks with associated specialized, intricate hardware crafted out of real atoms obeying real physics, with zero evidence that anything is going on that must defy vanilla physics. Damage the hardware, and I guarantee the associated capabilities suffer. It's a very stubborn and inconvenient foil to the claims that materialism is not the way of things. It's actually a rather remarkable spectacle, once liberated from the requirement that we master the whole scheme in our meat-brains.

So the "confusion" (suffered by others, not you) is due to "limited cognitive capacity"? I see.

Your paraphrasing misses the mark – machine comparisons *are* invalid.

Maybe it is all material (I can't know everything there is to know, so feel unqualified to say definitively that it isn't).

Nevertheless, It's not a question of differences in the complexity of artificial machines vs Nature's 'machines'. One might reasonably say that the world's largest supercomputer is more complex than a blade of grass. Yet the computer is obviously not alive. But you extrapolate this to construct the 'straw man' that there "*must* be a categorical difference and a fundamentally different operating principle, divorced from a purely material plane". No, not necessarily at all.

It could well be all on the material plane – the point is, we are capable of thought, and of reasoned actions (same goes for all life). We feel, we choose, we live, we die.

Machines don't.

Fair points. Having lived most of my life under the influence of what I now take to be an illusion, I can say that I would not have been able to reconcile my current perspective from that foundation. The "confusion" I speak of is one of personal experience. Embracing cognitive limitations (my own) allows dropping the requirement that the complex emergence be fully understood.

First, I doubt the supercomputer is more complex than grass, or a microbe. It's scaled up to huge proportions, yes, but the architecture is basically transistors in a few dozen functional arrangements and then copy-paste. Transistors are incomparable to neurons, having only a few connections and digital states (analog is much richer). So, I still hold to incomparable complexity. A computer is not alive, because it did not emerge in an ecological, evolutionary context whereby its arrangement of atoms was guided by feedback on the basis of survival *within* an interactive community of life.

The 'straw man' was directly triggered by your "living things are categorically different to machines" statement: not my own creation. But maybe it's where I went with this, because categorically different to me implies not materialistic. If you're willing to accept that it might all actually be materialism, then I suppose we're in full agreement. Then what's left to account for the things Life can do that our paltry inventions do not is heaps and heaps of intractable complexity, cooked over eons *in* *feedback* (hugely important) to be viable as reproducing entities operating in a material space. Clever beyond description, yes. But more than complexity? A very tough sell, lacking evidence.

Excellent reply.

It is incredibly difficult for humans (or, I suppose, any species that has some form of self-awareness) to accept that we're just a bunch of atoms, following the same laws of nature as a lump of rock. Even if we accept it, it will not make any difference to how we act (oh, I suppose that acceptance may alter synapses in some way – I can only hope). It is this simple fact (we are atoms following laws of nature) that shows free will to be an illusion because free will would require some mystical non-physical force than can act on physical stuff.

But it still "seems" like we have free will, and most would actually insist on that illusion, despite the only evidence being the feeling.

Yes, excellent conversation this one. I enjoyed it too.

But in this context, how is 'free will' different from 'free agency'? Because living things must have oodles of the latter to survive and flourish. They are as free as a bird to chose what to eat, where to go, how to avoid a predator, how to hunt for prey, and on an on.

If they didn't they would not be here.

Maybe in distilled form (always risky): free will is "you" telling "your" brain what to execute; free agency is "your" brain telling "you" what to do. The first implies some override/intervention control over neurons. The latter is compatible with "deterministic" physics (quantum probabilities thrown in): physical processes playing out the only way they *can* given their (non-random; selected) arrangements. It's a matter of whether some entity is "in control" or if that's an illusion cooked up by hardware.

As to survival, that is indeed the key: "choices" (acts) are not random, but tuned by evolutionary feedback (via physiological structures) to be adaptive. "Wiring" (or equivalent biochemistry for simple forms) is shaped by selection forces to make decent calculations, on average, weighing many simultaneous inputs. By using computer-speak, I do not wish to imply comparable levels of sophistication: Life is many orders-of-magnitude more complex, nuanced, and analog compared to technological contrivances. So: it's "free" only up to a point. I seriously doubt it's free of the physics we already know. It's also not entirely free (whether to eat, move, evade, hunt, etc.) in that arbitrary/random acts are unlikely to result in viability. An invisible constraint operates to shape our actions, but the prefrontal cortex is fooled into thinking it calls the shots—because it *does* perform some arbitration over what the "wiring" produces. But that is also wiring!

Daniel Quinn's sinking ship parable might belong here…

https://www.ishmael.org/daniel-quinn/parables/sinking-ship/

Given that nearly all political parties are humans supremacist, one approach (which is the one I take) is harm reduction: Which of the parties is the least malignant among them? Which candidate is least likely to make our situation unnecessarily worse?

[Replying to tmurphy's comment on 2025-05-15 at 13:04]

Well, I too have lived most of my life under the influence of what I now take to be an illusion. Namely that of 'progress' towards some 'higher state of humanity'. An idea so ingrained as to have become 'accepted wisdom', even thought it is very far from being wise (quite the opposite).

All we see and experience might be material, I can accept that. I merely say "I don't know". I cannot know.

"Opening the door to what is does not lead directly to what should be." A. Einstein – To open the door to what is and accept what is behind the door, regardless of preference, takes critical thinking and a certain amount of mental and emotional maturity that our modern culture is notoriously bad at inculcating.

Albert Bartlett distilled H. L. Mencken's philosophy to: "It is the nature of the human species to reject things that are true but unpleasant and to embrace things that are obviously untrue but comforting." Most people, I believe, come from the perspective that the world works the way they wish it to work and rationalize their beliefs accordingly, while the rarer actually rational person believes that the world works the way that it works, absent their preferences, and calibrates their thinking based on the best available evidence.

The fact that we took the name homo sapien for our species, 'wise man', is telling by itself. – Humans like to think that they're cool and special. A belief like 'consciousness is non-material and transcendental', in the absence of any compelling evidence to support such a claim, sounds more like a rationalized preference than a rational conclusion to my ears, and is thus easy to reject. Similar to the 'when we die we're not actually dead' tropes.

Whole-hearted agreement! Well put. Physicists (two of whom you quote) learned that we don't get to decide how the universe actually works. The best we can do is *try* to puzzle it out, ready for surprises and disappointment and bafflement—while the universe is indifferent to our reactions.

"I am not an atheist". A. Einstein.

How could anyone be so stupid as to believe 'non-rational' things?

Earlier in the history of human 'progress', figures such as Newton, Leibniz, Mendel, Maxwell, Schrödinger, Plank, Heisenberg etc all believed in God. Were they all stupid? Or astute observers of "the way that it works"?

It's no coincidence that modern culture, with its greed and its wanton destruction of Nature, is so materialistic. Indeed atheism could be the 'religion of modernity'. Via a wholly left-brained process, everything 'spiritual' has been labelled 'material' (the left brain being so keen on categorizing things). Thus, the wiser, right hemisphere has been occluded.

The sole 'bomb-proof' position (and the most humble) on metaphysical questions is agnosticism, but then the position of most contributors here (hardcore atheist/determinist) is an ideological one. Any take other than agnosticism presumes knowledge of ultimate reality – to which no one has access.

After reductionism is boiled down, all that remains is a nihilistic, amoral void. Now why would anyone *choose* such a depressing position? (Yes, it is a choice.) Not because "That's how it is". Rather, the hardcore athiest *thinks* "That's how it is" – big difference.

I often concede that I can only be agnostic, not atheist. That's after being a Christian for the first 19 years of my life. My position now, regardless of being either agnostic or atheist, is that whether there is a God has no impact on my life. I can't think of any rational explanation for why it would or should impact my life.

Just a caution that we cannot know what these same individuals would profess to believe today, given access to a greater accumulation of discovery in a culture more tolerant of non-religious views. For that matter, we can't know what they truly believed beyond the words they selected for public consumption by the culture of their day. Then again, as products of a place and time, these same individuals could not exist today: brewed in a different millieu (every being is a product of evolution and culture). Even if not stupid, we should not accept their public opinion as any evidence of truth.

Yes: it is fairest to say we don't know. My strong preference is to refrain from making up grandiose stories that make us feel better without a shred of evidence: keep it as simple and parsimonious as possible. Anything more is gratuitous embellishment. That doesn't make the simplest story *correct*, but at least it's trying to avoid pure fabrication where we can't justify claiming "more than" a complex material basis. If you were truly agnostic without preference, it seems unlikely you'd crusade against materialist supposition every time it shows up. It would be more like: intriguing possibility worthy of attention and we have no evidence to the contrary. That's definitely not the vibe.

"If you were truly agnostic"

So, I'm lying about being agnostic, am I, on my "crusade"? Lol.

I've already said, repeatedly, that the materialist position is a *possibility* (just that it's not the only one). I accept I'm in a minority here, and I get the distinct vibe – not for the first time – that you'd like me to shut up. Fair enough, it's your blog.

Replying to Mike Roberts on 2025-05-15 at 16:12: "But it still 'seems' like we have free will, and most would actually insist on that illusion, despite the only evidence being the feeling."

I wonder if you can follow up on that by saying more about this 'feeling' thing? Is this feeling merely a result of materialism/physicalism, like the pain of hotness, or more abstract, like the pain of regret, for example?

Why or how is the illusion of free will not in the same category as the inability to presume/imagine/assume that materialism is not a complete/sufficient explanation?

[Maybe more later, as I think more about Iain McGilchrist and James' comments]

In the sense that materialism means that everything we "feel" is the result of physical laws acting on the material of our brains, there is no difference. The laws of nature determine everything that happens and the current state of everything. Our bodies, including our brains, are made of real atoms which follow nature's rules. It cannot be otherwise, as far as I can tell. So the feeling of free will is the current state of the brain as determined by physical processes.

[edited for brevity]

I guess I didn't make myself clear. I do not argue with anything you write above. I agree that materialism seems to reach that conclusion.

I am questioning your (and Tom Murphy's) advocacy of materialism as the ultimate explanation. I do not think that consciousness, feelings, thoughts, are 'material' in their basic nature. I question whether or not they are even the result of purely material interactions.

While I do not deny the reality of atoms, electrons, charge, etc (loosely, materialism), I have basic doubts about the ability of materialism to explain consciousness, choice, free will, feelings, thoughts, life, as we know/experience it. [Having said that, I do not embrace 'God' as the answer. More importantly, I do not embrace 'emergence' as the answer either].

It seems to me that what modern physicists/biologists are doing when they invoke emergence as the solution for how neurons, synapses, chemistry, charge, atoms, electrons, etc, interact to produce consciousness, feelings, thoughts, etc, is pretty much a cop-out, very much like invoking 'God' is a cop-out. They might as well be saying, like in that cartoon in which the physicicst/advisor of the graduate student says to his protege: 'I think you need to flesh out this part here, where it says "and then a miracle happens", in response to the student's mathematics filled blackboard.

I think what I am trying to say is that consciousness, feelings, thoughts, free will (the experience of), are not explained by invoking the term 'emergence' [which is really all we have so far, when trying to explain consciousness, thoughts, free will].

First: Not insisting that materialism is absolute truth, as much as cautioning against fabricating new elements without even a shred of evidence (unlike knowing about atoms and their physical interactions).

Second: The universe does not care what I, you, or anyone thinks or believes, what we question, what we deny, etc. That's irrelevant.

Third: if thought, consciousness, free will, etc. did not emerge from material interactions, it takes a lot of explaining (fabrication) as to why sophisticated human capabilities are associated with sophisticated neural structures (comparative anatomy): what would be the point of it? Then, how can material (chemical) interactions with a tiny amount of substance (drug) be mind-altering or remove consciousness and free will entirely as in anesthesia? Some fancy dancing is required, there, and all purely speculative. It's FAR easier to say that consciousness emerges from material interactions, and that interference in those processes utterly disables consciousness.

Fourth: if one insists/demands/requires that an end-to-end explanation fits in our heads for how our experiences trace to material interactions with no gaps, that's *our* problem. If there's a short-cut or cop out here, I would say it's that "because we're not smart/advanced enough to trace the entire chain of events, we'll posit that it can't possibly be material in origin, based on no more evidence than preference or hunch." The insistence that we "explain" it all, in however shoddy or short-cut a way (by claiming not emergence; consciousness is not material, etc.) is problematic, in my view.

As for "miracle occurs," one could ascribe this to anything lacking a full account, and we do not have a full account of everything and never will. Saying our experience is God is in the miracle camp. Saying consciousness is not emergent is saying a miracle occurs. Saying it is emergent materialism could be labeled the same way, but I see a key difference. It requires no new fundamental interactions we have not already characterized. It requires no new actors other than the atoms, electrons, photons, etc. we already know. It's only saying that the complexity exceeds our capacity to track (presently). Really, doesn't it have to be the least "miraculous" of all the options? It's boring, vanilla physics requiring nothing new or unknown. I think it's why people reject it on the basis of taste. People would rather it be a miracle. I would say: not a miracle, but complexity we can only chip away at (as we do) possibly without resolution (before modernity crumbles).

Another great reply, Tom.

I shouldn't be, but I'm constantly amazed at how humans just ignore the knowledge we've amassed (even though it's incomplete) to believe in things which have no evidence. If only we could accept what is in front of our noses instead of imagining stuff – in all aspects of our lives.

Tom, when I read things like “The universe does not care what I, you, or anyone thinks or believes, what we question, what we deny, etc. That's irrelevant”, I have a kind of puzzled feeling. Maybe it’s because I am misinterpreting the sense in which it is meant, or perhaps I have a need to feel special that I am not acknowledging, or perhaps I am just an idiot that doesn’t get it all yet (highly likely!).

Say I am a person that thinks dogs are horrible and that it is ok to kick dogs. I kick very dog I see. The dogs I frequently encounter on my walks start avoiding me when they see me. Am I able to say that this is because the dogs (part of the universe) care about what I think, because my behaviour is linked to what I think? Or can I only say that what they care about is avoiding being kicked, and that what I think is irrelevant to it all. Am

I just playing a word game in my head here?

Can I at least say that my family (also part of the universe, albeit an incredibly small one), care about what I think?

I also seek clarification/help here because I see myself as part of the universe that cares about what other humans and animals think, but again, I could be deluding myself.

I'm glad you ask this, because it points out an important narrowness in the context I intended. That context is: the universe will "be how it be" no matter how we think it should be. We don't get to make up or decide reality when it comes to things like physics, cosmology, evolution, etc. Brains readily create models divorced from reality, and the universe shrugs, effectively. Basically, our thoughts don't dictate reality. Believing we're all in a simulated reality does not make it so. Believing in God or souls or primacy of consciousness does not alter how the universe actually works.

My first reaction to your useful dog scenario was: the dog responds to your actions rather than your thoughts. But of course actions are connected to thoughts. And in this context, I suppose that's why I care what people think. Some thoughts lead to bad actions and outcomes. For me, human supremacy is one of those destructive patterns of thought I'd like to see diminish.

Primarily, the statement is one advocating humility: were not the masters; we don't set the terms for the universe, but rather the opposite.

In Europe(Belgium), the spectrum has always been multi dimensional. We have

– right/nationalist

– left, libertarian

– socialist ( who have in that past realized the socialized healthcare and much of the social security present in Europe, but their ideas are now so mainstream (no one will argue against free healthcare now we have it) they find it hard to differentiate themselves

– communist ( fringe movement)

– green ( who have had nature on the agenda since decades, and perhaps others may now have to admit the greens have always been right, the greens are put away as unrealistic tree huggers. This carries within itself a contradiction (they are both right and unrealistic) that I find hard to understand.)

– catholic

….

So this view is, while valuable, very american.

Just as the visible spectrum contains more than red and blue, the left/right political spectrum can have other "colors" ordered (loosely) along an axis. That is: a left–right spectrum is not synonymous with "two party system."

Communism is more left then socialism, which is more left than liberalism, which is more left than libertarian, which is more left than nationalist, etc.

See: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Conventional_political_spectrum.svg

I agree that the greens might dabble outside the normal bounds, but as far as I know none are calling for dissolution of money, markets, agriculture, cities, governments. They just want a modicum more consideration for the "natural" world while maintaining familiar structures. This is what being so far left looks like: to a hunter-gatherer, for instance, a Green would be practically indistinguishable from a fascist. A shade better, no doubt.

Isn't this standpoint called primitivism?

I've been enjoying the materialists debate.

Just to wade in with a few of my own thoughts.

@tmurphy.

Can a "weather" analogy be used to describe your position?

That, if all the vast interconnected factors that create weather patterns could be turned into data and inputted into a "Deep Thought" size supercomputer, then accurately predicting the weather could be possible?

After all, it's just physical "laws" that are in play. Nothing random, but so complex, that we can't possibly see all the data inputs?

The same goes for us humans and our actions. We are products of long lines of inherited genes, plus cultural influences, plus environment. If all those inputs could be "mapped", then predicting someone's "next move" would be possible????🤔

Predictability is out the window: no chance. It's more than the practical matter that no machinery is capable of tracking all the inputs (by 20 orders-of-magnitude or some such) but that particle interactions have a probabilistic element (confined to select outcomes and exact probabilities in each instance, but still). The only "computer" powerful enough to reveal what happens even a nanosecond into the future is the universe itself, running in real-time.

Predictability and determinism are distinct concepts. A deterministic universe—and especially a quantum one—might be following rigid rules all the way down, but defies complete predictability. All the same, human behavior *tends* to be confined to a small subset of outcomes. Self-preservation is *usually* a good guide (not likely to jump off cliff or just stop drinking liquids), and one can toss out most random possibilities that come to mind (standing on head; speaking gibberish; eating a rock)…unless the person knows that their behaviors are being watched for predictability, in which case random acts become FAR more likely (predictably).

This is because Life is formed in feedback so that behaviors tend to promote survival and passage of behaviors in a reinforcing way. Randomness is honed into sensible behavior.

Oh I like this, thanks for the humor:

"…unless the person knows that their behaviors are being watched for predictability, in which case random acts become FAR more likely (predictably)."

What comes to mind is the HR statistics from global firms observed, that the 'agreeable' trait from the OCEAN 5 is far more prevalent in their staff in Asia. Apparently, expectations can shape even subconscious traits.

I understand that it is impossible to create a computer that could possibly come close to predicting outcomes because the cause and effect inputs are too vast.

But………. If all outcomes are governed by the laws of physics, then is there such a thing as "random" at all.

An act that appears to be random is actually predictable if all the inputs where quantifiable?

As far as we understand quantum mechanics, probabilistic outcomes are truly random and unpredictable. Many have sought "hidden variables"—relevant measures we are not clued into—but never with any success, experimentally. So, it's more than computational power limits, as real/relevant as that is, too. In principle, a computer of "infinite" potential could chase down all the probabilistic paths as well (with known "branching ratios," but it's again utterly impractical.

I'd call it "ordered randomness"—randomness within strict/known parameters and probabilities. Still unpredictable, except that it will do one of the available choices at some quantifiable probability.

Interesting stuff. I'll have to chew over that a bit.

So if randomness does exist, can thoughts be random?

Is a Eureka moment "preordained" or random?

I guess, it goes back to notions of "fate". Something humans have been grappling with for a long time.

You say……

"I'd call it "ordered randomness"—randomness within strict/known parameters and probabilities. Still unpredictable, except that it will do one of the available choices at some quantifiable probability."

Using a football analogy……

The rules of Association Football set the parameters of what is possible in an game, but no use in predicting the final score or how the game plays out????🤔

I am currently reading a book with the title The meaning of the twentieth century written by Kenneth Boulding with the subtitle The great transition.

After reading half the book I think you who read Do the math would find the book interesting even though it was published i 1964 in New York. There has been a reprint 1988 but is sold out. I found the book at the library at a Swedish university.

I was recommended the book by a professor and researcher in physics at one of the universities in Sweden who is very much against the growth.

The chapters of the book are as follows

– The great transition

– Science as the basis of the great transition

– The significance of social science

– The war trap

– Economic development: the difficult take off

– The population trap

– The entropy trap

– The role of ideology in the great transition

– A strategy for the transition

You can find some information about the book on a Swedish publisher's website

https://www.bokus.com/bok/9780819171023/the-meaning-of-the-20th-century/ where it says "As relevant today as when it was first published in 1965 by Harper and Row, this book looks at the 20th century as a critical era in the great transition from a civilized to a post-civilized society. The 20th century itself is seen as an ongoing evolutionary process. The author focuses on three "traps" which would prevent this transition from taking place: the "war trap", the "population trap", and the "entropy trap". And he outlines strategies for the 21st century for overcoming these traps."

@tmurphy

More on the 'free agency' discussion (I enjoyed the exchange immensely);

as I am reading into wo sources in particular to crack this a little more open:

one is Ashby's 1961 classic "Intro to Cybernetics" (the precursor of his Design for the [meat-]Brain); and the other is "How Life Works" by Ball, a (former?) editor of Nature), in which he challenges the exclusivity of the 'natural selection' trope and primacy of genes on traits and behaviors.

I think a key element in your insight into free agency is the notion of 'you' IF (and only if) that 'you' has capacity to wield the control of override on the hard wiring of the meat-brain. Where hard wiring encompasses, though not exclusively, the weight adjusting for the thresholds to fire across synapses. There are several aspect of this seat of control, which construct we could call the *self*, while associating it with some kind of meta-wiring.

The first is that for social animals, this construct of self is recursively constructed through social actions by individuals. Then, this *environment* can feed back epigenetically (thru methylation tags in the lifetime of the self, not through selective pressures) even on fixed behavior of the individual. The implications are profound. First, without 'others' there is no self; it discombobulates. Second, as the meta-mathematics of the Yoneda lemma shows, the internal constructs of any object, however complex, can be fully defined by its external relationships to other objects in any category we care to choose or formulate, with whatever rules or syntax for whatever objects, be they themselves some categories. Meaning, that even a discussion about this may be epistemically bound.

To illustrate, I would choose two non-human examples to escape the trap of human supremacy. Suppose the 'Brownian motion' of any individual (self) in a grazing herd of social animals appears haphazard to an external observer. Yet, we would also say they each follow individual urges, be they hormonal, digestive, social, energetic, etc. The herd on the whole, on the other hand, becomes a complex, self-organizing, goal-seeking object. Not only this combined behavior cannot be deduced from the individual sheep, blades of grass, drops of dew on the blades, etc., it cannot be divorced from any one of those either. Ashby's example, on other hand, is a group of mobile robots with photo-sensors that are programmed to be light-following. Their motion will be completely determined if they follow any number of light points flashing, however fiendishly they are programmed to do this. But when you furnish them with a light source, you endow them individually with the slightest 'free agency' of flashing lights on each other. You can make those flashes hard wired as a preprogrammed sequence, or responsive to the other robots' action. The result will be the same: chaotic non-deterministic movement, impossible to deduce from its constituent parts, its components.

I would imagine the similarly non-deterministic 'free agency' of the self as some such. Any complex whole can acquire self-organizing and goal-seeking behavior, be they an individual or a crowd of individuals. To an external 'observer' even fully knowing the constituent vectors of state-change of each part (movement being but one of them), the behavior of the whole will be elusive; non-deducible from its (material?) parts, though apparently self-serving. And its components are necessarily multi-body; in the case of an octopus its skin can think and so are its eight connected brains, it the case of humans the meat-brain is a ganglia of neurons but so are the neuronal ganglia of the heart, the gut and spinal chord connected to it.

I left the notion of 'material' here bracketed with a question mark, as matter itself can well be viewed as constructed from relationships; chaotically and non-deterministically defined but not fully deducible from the many fields it generates. These meaning the fields that somehow each generate it-*self* or in combination with others, while viewed by an external observer as self-organizing into the various form of *matter* we so far catalogued, from quarks, to meat-brain to nebulae and beyond. In other words, it is a chicken and egg for matter and form for me, in general; matter and substance may not take precedence over form and relationships but, then, nor is it the other way around. However, as for any complex enough systems, one may find the one or the other reasoning more plausible, different observers and situations permitting.

An attempt at a succinct summary: feedback in its many forms (including epigenetics) opens the path to a rich set of behaviors that tune themselves and become "selected" by their performance in response to the feedback condition (survival being the ultimate feedback condition for Life).

As for fields/relationships. 98% or more of the content in physics books is taken up describing the relationships (interactions) between the actors (particles) and very little space on the actors themselves. It's a rich set, providing ample room for all kinds of mind-boggling complexity.

And, indeed, the chicken–egg aspect is apt: trying to separate the two is where the mistake lies. That's our left (meat) brain doing what it likes to do.