Recent posts have compared belief in a space future to belief in Flat Earth, and also compared living in space to hijinks like keeping a crewed airplane flying for over two months straight. Indeed, a number of insights might be gained by comparing the quest for flight to the space ambitions that followed.

Long before fuel-powered flight was demonstrated in 1903, human-powered flight had been a perennial dream of early inventors. It wasn’t until decades later that the much harder task of human-powered flight became possible—aided by modern lightweight materials. Yes, it can be done, but only if you’re a world-class athlete and content to travel at running speed a meter or two off the surface (remaining in ground-effect). Likewise, supersonic commercial flight is possible but not practical enough to remain an option. And it is possible to keep two people up in an airplane for 65 days.

Just because something can be demonstrated as a stunt does not mean it is destined to become normal practice. In particular—as I pointed out in an earlier post—occupation of a space station shares a lot in common with sustaining people in continuous airplane flight, which was once quite the enterprise. But after 1959, people stopped even trying. The exercise had crossed the line from meaningful to a silly waste of effort.

In the first half of the 20th Century, few (in techno-industrial cultures) would question the merits of attempting to keep people airborne as long as possible. It was exciting—proof of man’s greatness and progress into the novel. Given some degree of technological development since that time, we could presumably beat the 65 day record by a large margin, perhaps even demonstrating indefinite airborne capability—if sufficiently driven and provided adequate funds. But the proposal would likely—and fittingly— elicit shrugs and questions as to what the point would be. From my perspective, similar responses should accompany proposals for living in space. The question, then, is: when will we collectively become comparably dismissive of proposals for humans in space?

Becoming Bored

Other outsized feats of exploration peppered the past era: polar expeditions, conquest of un-climbed mountain peaks, diving into the depths: records, records, records. Part of the fuel is a quest for the superlative: to be unambiguously marked as “the best” in some narrow category. The psychology is fascinating. But it’s not just the fanaticism of expedition personnel; public engagement and enthusiasm also speaks to a shared sense of accomplishment for the human race (race to what?). Impressive stunts serve to reinforce and validate human supremacy. It’s almost as if modernity needs the psychological reassurance of novel conquests—even if pointless—to keep the doubts at bay.

Our culture seems to remain enamored of the “frontier” derring-do of humans in space, even if we have lost the zeal for treks across ice plains. And it’s not because ice treks have become part of daily life that a sizable fraction of humans now experience, routinely. We just lost interest in something that is really hard and seems to have no purpose, other than pushing limits for the first time. Can’t we imagine the same fate for space: of being bored by the stunts?

In fact, I used to poll students—all born well after 1972— as to how far humans have traveled from Earth’s surface in their lifetime. I would draw, to scale, the five choices on the chalkboard relative to a circle representing Earth:

- 0.1 Earth-radii (600 km; hugging the globe);

- 1 Earth radius;

- 6 Earth radii (geosynchronous);

- 60 Earth radii (moon; far end of chalkboard);

- Beyond the moon.

About two-thirds of students would distribute among the last two choices, even though the first answer is correct (only about 5% would pick this). Students bordered on anger—certainly shock—when they learned that we hadn’t even been as far as the moon since 1972, asking what the Space Shuttle was even good for (back when it was even still a thing), and imagining the Space Station to be beyond the moon, like it would naturally be in movies or TV shows.

To them, even traveling to the moon had become passe: already boring. Given that farther steps may forever remain out of reach, we may have reached “peak stunt” over 50 years ago! Sure, we may see repetition of humans on the moon, but will humans actually ever make it to Mars? While I have serious doubts, I wouldn’t rule it out. Even so, I would strongly expect it to be another short-lived stunt—this time more likely holding the “forever” title.

As mentioned in the 8 Billion Will Die post, Mary-Jane Rubenstein experienced a similar disconnect in her class (as she discussed at the end of this podcast episode): students had a harder time imagining realistic/demonstrated modes of human living than fantasy space scenarios. We’re really whacked!

The Flight Craze

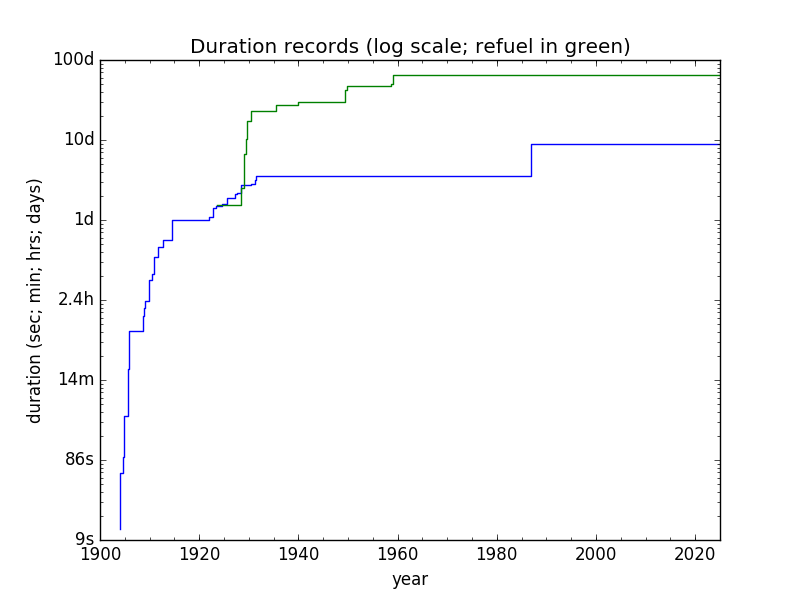

It is instructive to look at a plot of flight duration records to get a sense of the “craze” period and the bored stagnation that followed. The first is on a linear vertical scale, showing lines for both the no-refuel flights (blue) and refuel-on-the-go operations (green). Shortly after refueling practices began, the records left single-fuel metrics in the dust. In fact, no-refuel attempts essentially ceased (having become silly/pointless), until the 1986 event when Rutan and Yeager circumnavigated the globe in 9 days.

A logarithmic plot better reveals the early history and also displays a characteristic curve that applies to both lines. The appearance is of a reversed, upside-down exponential (1 − exp(−t) form): an initial flurry of record-breaking as low-hanging fruit is plucked, followed by stagnation as it gets ridiculously hard and increasingly pointless and eventually silly.

Consider the rapid pace of space superlatives racked up in the 12 years from Sputnik to Apollo. But it’s been over 55 years since the “most distant person” record was broken. [The distance record was in Apollo 13; April 15, 1970; 406,542 km from geocenter.] Even if we do return humans to the moon, we basically only tie the record. It would not be foolish to bet that the most distant human record for all time mimics the flight duration curve. If we ever do take the dramatic step of putting a (living) human on Mars, chances are quite high that it becomes the eternal record—for all sorts of reasons.

The burning question is: why does the airplane stunt strike us (collectively) as silly, while the very similar stunt of maintaining humans on the constantly-refueled space station does not? Especially in the context that the latter is more than 3,000 times more expensive to carry out, is the relative gain worth the expense? Will our space stunts one day also be viewed through the “silly” lens by more than a few heretical individuals?

The answer to these questions hinges on expectations for the future. To appraise intrinsic value in the here and now, we have to evaluate as if the space effort does not proceed. In other words, a primary argument for valuing humans in space today is predicated on a belief that these are crucial and necessary baby steps toward a continued/expanding space presence tomorrow. Take that away—because such an outcome is very far from guaranteed—and what meaning is left for the present-day dead-end stunts? Anything? Does it make sense on its own present merits and at such tremendous cost? Do we learn things that are still “useful” in the absence of a space future, and could not be gleaned (given similar investment) on the surface of the Earth, where the context is more applicable?

Of course—seeing that I value Life on Earth more than I do economic expansion—I would claim that the “advances” deriving from the space effort mainly advance a sixth mass extinction, and therefore have an overwhelmingly negative impact, ultimately. Maybe it’s unfair to claim that space has had zero positive impact. For several seconds in 1968, the image of Earth rising over the moon gave people pause by pointing out our isolation in inky space. But that lesson of treasuring Earth above all seems not to have lasted very long.

NASA’s Case

Presumably, few institutions have made a greater effort to nail down the case for human spaceflight than NASA. A representative resource providing various links to explore is their Why Go to Space page. Let’s look at some of the text pulled from this site.

Since the dawn of humanity, people have explored to learn about the world around them, find new resources, and improve their existence.

Ah—resources and improvement (progress): feeding modernity’s growth imperative and the inevitable suffering such a twisted goal brings about. But this part was preceded by an appeal to mythology. Yes, the statement about exploration contains an element of truth, but only in the context of all kinds of limits. Do we explore what it’s like to sit on a bonfire? Lie naked on the ice for a day? Live in an airless underwater cave? Don’t be absurd. Even though these don’t cost money, we fail to explore them. Blanket platitudes leave out an awfully large amount of relevant context: they’re a poor and lazy substitute for critical thinking. Limits apply!

…and inspiring the world through discovery.

Inspiration is valid: I’m sure people were inspired by the flight duration tests as well. Entertainment and stunts are a form of inspiration, and that’s fair. Viewing human spaceflight as expensive entertainment makes a great deal of sense, and I myself have both enjoyed the spectacle and built part of my career on the activity. But what exactly would be the point of inspiring people—and a young generation—on false pretenses for something that will cease to be a part of the human experience?

Technologies and missions we develop for human spaceflight have thousands of applications on Earth, boosting the economy, creating new career paths, and advancing everyday technologies all around us.

All hail the mighty market! Yes: there’s money to be made (and ungodly amounts to spend). I’m not sure how one would make the case as to whether a human presence in space (setting aside satellites and other uncrewed tech) is a net accelerant or net drag on the economy—pretending for a moment that what’s good for the economy is good for Life (including humans). The companies that benefit are not self-supporting, but rely on federal spending based on tax revenue. The industry doesn’t appear to support itself (or would not need a federal penny). But yes: a big infusion of tax dollars into the economy will create jobs and advance technologies. Yay—if technology is your god, and extinction your goal.

Uninspired

I was not impressed by NASA’s public case. Notably absent from the page is talk of colonization, which is the unspoken driving force. I did find some mention in the Destinations menu item. Even here, two-thirds of the content concentrates on modest goals, and what remains falls short of discussing colonization. NASA does have a colonization page. Its content first acknowledges the sci-fi allure, then talks up the International Space Station, before listing the numerous daunting challenges to living in space. It’s not a full-throated embrace of colonization, despite what NASA Administrator Griffin said in 2003: “For me the single overarching goal of human space flight is the human settlement of the solar system, and eventually beyond. I can think of no lesser purpose sufficient to justify the difficulty of the enterprise…” Maybe since then they’ve cooled their jets? Without that unrealistic goal, their case for pushing the stunt show is considerably weakened. Maybe we’re approaching the boredom stage, which would be a huge relief for the collective good.

[Late addition 2025.11.05]: Even more important than direct damage from the wasted activity is the promulgation of a delusion that makes people believe and act as if Earth is disposable. Faith in a space future both excuses and encourages a destructive attitude that only digs our ecological hole deeper. For the worst among us, that may even be the entire point!

Views: 3273

Some hints of future impulses can be found in the inhabitants of Rapa Nui. With an equally epic ending.

I thought that was since debunked. Research says Diamond left out from his analysis the visitors, who kept taking away as plantation slaves a good chunk of the local male population from the island.

The old stories about Easter Island were probably wrong.

https://magazine.columbia.edu/article/what-really-happened-easter-island

Paul Cooper did a nice episode on this more nuanced perspective (relative to Diamond) of Easter Island history:

https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=7j08gxUcBgc

Thanks, Alex. I haven't had time to watch all two hours or so but the explanations of how the statues might have been "walked" to their locations and of how contact with civilisation had bad outcomes seemed very rational.

@Yevhenii

Don't you love these creative accidents? I do! Incidentally, it looks like Yevhenii just provided one of the best counterfactuals: rock farming on an ecologically limited footprint; ingenious, robust and it sustains a stable population.

What not to like about it? Imagine also a community that regularly reaffirms their commitment to each other by 'walking' with freshly tensed ropes between two large synchronous groups another rock statue to overlook the horizon. By standing them in a row and with slight modification to each, it is both a diary marking time and a symbol of the continuity of their ancestral tradition to be proud of.

That is, until a bunch of invasive human supremacists come in a spoil the party. This last bit they could so do without…

The healthy case for space is simply observation. I wonder what level we could settle upon in future? The telescope? A shared observatory, created as a shrine to the stars? Or are both simply unsustainable monuments of the civilised world.

Good point: no one can or ever will take away the awe of drinking in the night sky from our Earthly perch.

I agree–it's time to stop the silliness. But it's unfortunate that, as remarked in a classic Simpsons episode, "Now we may never know if ants can be trained to sort tiny screws in space!"

It’s been good fodder for movies—2001, Apollo 13, The Martian…

To combine your points about dumb flying stunts and dumb space stunts, imagine if somebody decided to break Oleg Kononenko’s shocking record of 1,111 (non consecutive) days in zero gravity, but instead of going to space they did it by spending about 3000 days flying parabolic routes on a ‘vomit comet’ small airplane. This too would actually cost hugely less money than somebody trying to beat the record in space, but would appear a far sillier stunt to most people.

While not taking issue with the absurdity of the astro-futurist enterprise, a couple of points come to mind. If space exploration is a waste of resources, ie. the money and energy could have been but to use more "efficiently" on earth, might that not be regarded as a positive, in that putting money and energy to use efficiently is the essence of our problem. Suppose that after abandoning hunter-gatherism societies had devoted all their surplus energy to space exploration – eg. ascending mountains, developing bird suits, shooting themselves out of cannons – might a 6th mass extinction have been averted?

More seriously (but in a similar vein), there is the question as to whether we (homo sapiens) have a future or not. If we do, then it could be reasonably argued that the various exploratory stunts are a distraction from what should be our primary focus – of trying to reduce our footprint on the planet, and perhaps even undoing some of the harm we've done. If we don't have a long-term/indefinite future, the argument seems to me less convincing. In that case, space exploration is a bit more like mountain or rock-climbing – things that are pursued (by a minority of individuals) not in the expectation that there will be ever steeper rock faces and higher summits – but simply as something done for the exhilaration of doing them, in the knowledge that they are dangerous, but that we are going to die (at some point) anyway.

The paragraph starting "Of course" touches on this a bit: the entire modernity enterprise is promoting a 6ME. But rather than diverting or distracting, space *adds* to the harm: the impact of a human in space is 2,000 times that of a global average citizen, the harm transpiring right here on Earth.

I don't perceive the space quest as a distraction from modernity, but an integral part of it: advancing the delusion that we are masters of all. Moreover, fueling a belief in a space future makes people less committed to doing right by Earth, if it's just the cradle we can leave full of baby poop.

Hmm…I know Second World War analogies are a bit done to death, but given your frequent citation of the "Human Reich", perhaps try this out. For Hitler, the conquest of the Soviet Union was as an integral part of the Nazi enterprise as the conquest of space is for many a techno-modernist. Admittedly, the Martian winters leave even the Russian ones seeming rather balmy, but the challenge was still daunting (no autobahns, railways the wrong gauge, logistics largely dependent on horses etc etc. More prudent National Socialists might well have argued that this was a step too far (at least in 1941): that the priorities should have been to knock Britain out of the war, secure their situation in North Africa (or abandon it), get the Japanese fully on board for a combined assault, not drag the US into the conflict, etc. (As well as a few other matters such as eschewing attacks on "Jewish science" and instead trying to keep the nuclear physicists under his control rather than driving them into exile). These (from the POV of Nazism's long-term success) might have been "reasonable" policies – and had they been followed the swastika might actually be flying over much of the world today. As for costs, it was clearly much cheaper to keep a German soldier stationed in France or Poland rather than in the suburbs of Moscow or the ruins of Stalingrad. The point is that Operation Barbarossa was unreasonable or even insane (in a less blatantly obvious but somewhat similar way to the various schemes for space colonisation) and that this that lead to the downfall of the Third Reich – and might not this same sort of insanity hasten the downfall of the "Human Reich". This is not to say that our rather puny efforts at space exploration need to be eulogised (any more than the Germans' initial triumphs in 1941). The more general point is that while we may be pretty confident that "modernity" is doomed, it is, at least as far as my own meat-brain is concerned, impossible to know what the way out of it looks like: in much the same way as that one can pretty confidently say that a ball released at the top of a steep rough slope will head towards the bottom, while not be able to specify which path it will take.

There is also one point on the flip-side of this. Before the advent of modern astronomy (including space-based), we had no idea of the density and courses of asteroids and comets. While I fully accept that our technological civilisation is a far greater threat (in probabilistic terms) to the biosphere than another Yucatan-style impact, we only know this because we have developed the necessary technology. Putting aside all the other space nonsense, the one just about conceivable bit that might be of benefit to the community of life would be the ability to deflect an approaching astronomical object. One could, I think, argue that even if there was a general return to pre-agriculturalism, maintaining a small technological core capable of monitoring and interception might be of value. One could also imagine that if we have a say a 100 year window of interception capability (before the collapse) and Chicxulub events occur every 100 million years or so, we might (with a 1 in a million chance!) be in just the right spot to have benefitted the global community. Again, I'm not really advocating this: I'm pretty sure that collapse will be global and that the prospect of maintaining any sort of space monitoring infrastructure is vanishingly small, all I'm trying to highlight is our fundamental ignorance in regards to the future.

@Philip

I believe the analogy with respect to our future is apt, but with a twist. Here it goes:

They say that the amount of excess heat we, i.e. modernity, have slowly and relentlessly released into the oceans since preindustrial times is already on par in magnitude with the Yucatan encounter released into Earth all at once.

So, even if we are in luck and can set up the kind of monitoring you wish for, we still wouldn't have avoided this first encounter; not a maybe but already certain.

The first airplane flight was in 1903, but will there still be airplane flights in 2103? – The whole enterprise of humans flying around all over the place seems silly given the inevitable absence of fossil fuels.

To add to silly space proposals, big AI proponents are now advocating for putting AI server farms in geosynchronous orbit as a means of offsetting their energy consumption.

To suggest that the reason for the ISS's existence is a "mere stunt" strikes me as excessive rhetoric. I understand that this is how an environmentalist might describe it (with very good reasons), but it remains a "literary license" that only reflects the author's perspective. Reasons behind the ISS's existence have nothing to do with media-impressive or socially approved feats. The scientific community sees it as a tool of purely practical, systemic and scientific value…period. It's not there to be a monument to humanity or a stunt that's just an angry perspective.

In fact, we don't know if society in 1958, when they saw the Cessna 172 fly by, thought>: "Oh what a hero, what a feat!" perhaps for people on the street it was just a good commercial for Cessna and Continental engines…I wouldn't rush to sociological conclusions about it. What I would venture to say (and I'm sorry for the Occam razor here) is that when they "let fall" the ISS it will probably be because the technical reasons that justified its maintenance are no longer there or because the economy has collapsed…but I highly doubt it will be due to a change in the average citizen's macro vision regarding ecology or a softening of the species' "conquering temperament".

I appreciate this pushback, and indeed I am completely speculating about cultural attitudes in 1958. In part, the rapid flurry of ever-increasing flight duration records signals to me that it was a "thing" and now is very much not.

As for the ISS, I was in the community. Scientists didn't want it. Even as a microgravity test environment, it was always pretty lousy: lots of vibration and a solar "slam" cycle every 90 minutes or so as the enormous panels came in and out of sunlight, also causing thermal cycles on board. The game was to try hard to concoct reasonable experiments because funding opportunities were available, but it was a stretch. The ISS was not driven by scientific demand, but some scientists were able to make lemonade from the lemons. The rhetoric was laid on thick about the scientific value (what else would we expect?), but the scientists I knew (within the NASA fold, to be clear) rolled their eyes as others scrambled to identify easily-funded applications.

Thanks Tom for the reply to my previous comment: as I said, I'm not heavily invested in the notion of space monitoring, even if it might have been (in a happier parallel universe) a good thing. I suppose my main somewhat nit-picking issue with the space topic is that there are two broad divergent outlooks on our predicament: one being that it is something that we as (99.9% of) the species have brought upon ourselves, the other that it is essentially the fault of the "Man" – read for that what you like: capitalists, oil companies, tech-bros, militarists, mad scientists and, yes, NASA and Space X, and that the rest of us are more like innocent victims than active participants in the destruction of the biosphere. Psychology being what it is, the latter outlook is generally more appealing.

Clearly there are vast differences in the amount of destruction that different individuals or different practices perpetrate, but fundamentally we are almost all part of the "modern" enterprise. While "space" is, on some pro rata measure of energy expenditure, perhaps outside of warfare, our most profligate activity, it is still a very small portion of the overall human project. Furthermore, the traditional criticisms of "space", at least from the "left" of the political spectrum, were not concerned with rolling back modernity, but rather that it was a diversion of resource from the human project (ie. modernity) on earth. I suppose it depends on what one sees as symptoms and what might be causes, and I see "space" as predominantly the former.