[An updated treatment of some of this material appears in Chapter 8 of the Energy and Human Ambitions on a Finite Planet (free) textbook.]

I’ve been maintaining “radio silence” for a while—mostly on account of an overflowing plate and several new new hats I wear. All the while, I have received a steady stream of e-mail thanking me for Do the Math, asking if I’m still alive, and if so: what do I make of the changing oil situation? Do I still think peak oil is a thing?

Let’s start with the big picture view.

I was wrong about everything. Oil is not a finite resource: never was and never will be. We will employ new technologies and innovate our way into essentially perpetual fossil energy. We’ve only scratched the surface in exploration: there are giant deposits (countless new Saudi-Arabia-scale fields) yet to be discovered). The shale oil tells us so—and it won’t stop there. Shale first, then slate, marble, granite: just squeeze the frack out of rocks and we’ll get oil. Meanwhile, whole new continents are being discovered, rich with resources. The most recent was hiding behind Australia. And naturally it doesn’t stop there. We have now discovered thousands of planets just a hop away, most of which are likely to contain fossil fuels of their own. So game over for the resource limits crowd, yeah?

Oh wait. I was wrong about everything in the preceding paragraph.

Wait—which is it?

Let’s not get confused, people. Earth is finite (and other planets are mostly in hostile environments and in any case rendered immaterial by unfathomable remoteness). The resources are finite. One-time consumables will peak in their use one way or another: they must do so—either by depletion or by voluntary reduction in use. Estimating timescales is the tricky part. But do I still believe in peak oil? As surely as I believe we landed on the Moon.

What about timescales: do I believe we are likely to see peak oil in the next decade or so? I do still think this is likely: a point of view based on more than stubbornness.

What’s Happening in Oil?

A good first step in anticipating the future is to understand the present and recent past. Why the dramatic price drop? In two words: shale oil. No big surprise. This is the story. The geopolitics add complexity to the tale, but essentially—as I understand it—OPEC is trying to run shale oil operations in the U.S. out of business.

Shale oil is more expensive to produce than conventional oil. Technology has its price, after all. The Saudis and friends have pledged to hold oil prices low for a good while in an attempt to destroy the market viability for U.S. shale companies to continue operation. I can’t say if this will work (the key question: how many years does it take to starve a company into liquidation of assets?). But that’s the not-so-secret word on the street.

So we need to understand something about the shale oil boom. Firstly: is it really responsible for the apparent glut? Secondly, can we expect it to last?

Recent Data

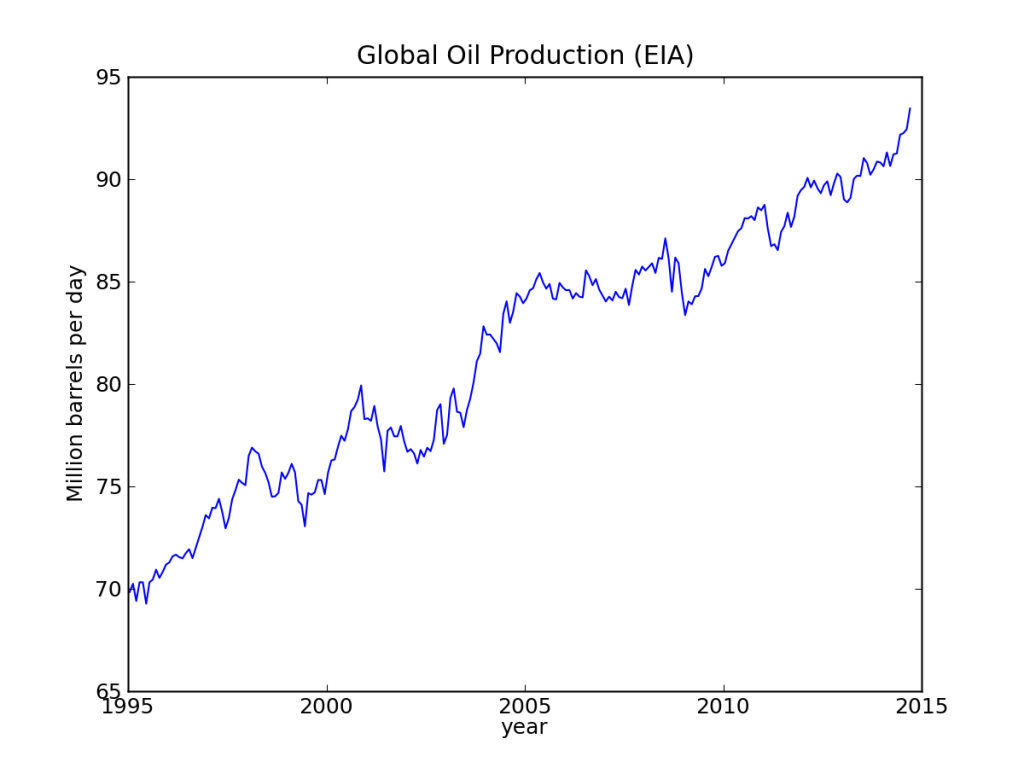

The U.S. Energy Information Agency maintains global data on oil production. Plotting the data for the world appears as follows.

At a glance, we see an inexorable climb in oil production. No evidence for a peak here. If we cover up the right-hand side, beyond 2009, we can justify a different narrative: production hit a plateau from 2005 to 2009. During this time, oil price crept gradually from $45/barrel toward $100/barrel and then spiked in 2008 at $140/barrel. This factor-of-two price hike had no effect on production, which strongly suggested a tapped-out world: pegged production.

One can make a compelling argument that the slow price increase strained businesses in many sectors (tourism, auto manufacturers, airplane industry, etc.), and that the resulting lackluster growth popped the housing bubble—itself built on the fantasy of perpetual strong growth. When the 2008 recession hit full force, demand dropped and took the price plunging with it. Yet global production didn’t flag that much: again reinforcing the story that oil is a highly inelastic economic commodity—on account of there being no ready substitutes.

But then the plateau disappeared into the ensuing continuation of growth, making a once striking feature now difficult to discern.

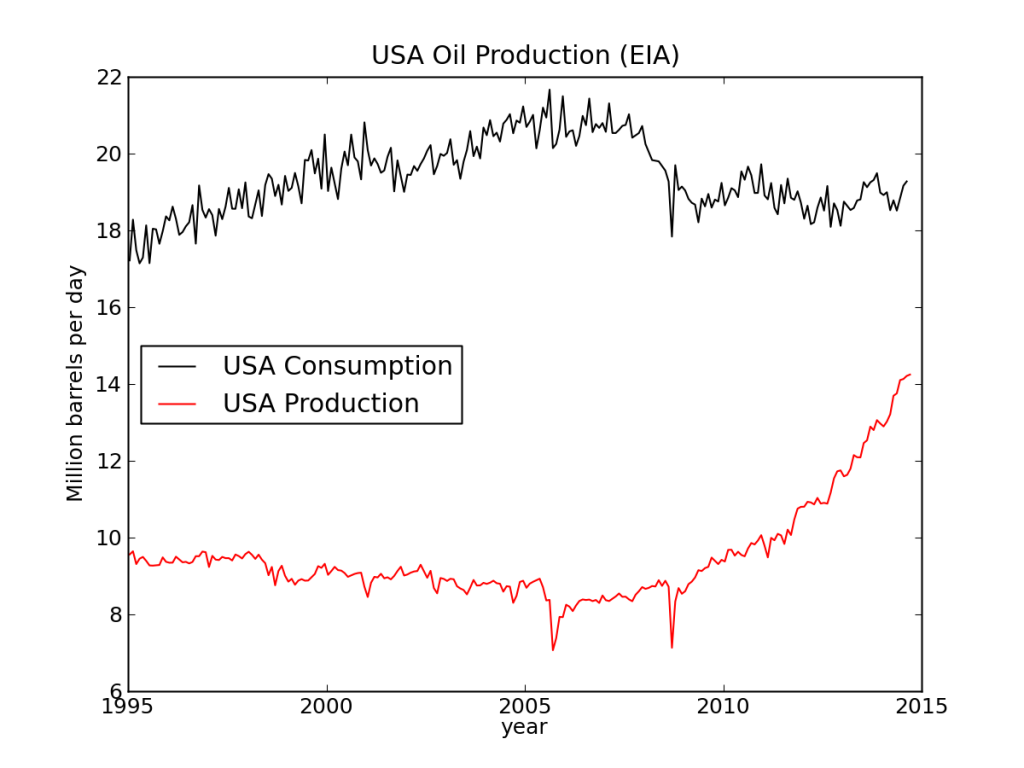

Let’s flip to the U.S. production to see what influence shale oil has had.

As the century odometer rolled over, we found ourselves in a slow year-by-year production decline, tucking below 9 million barrels per day (the scale of consumption in the U.S. is about 20 million bpd). Then came shale oil and what can I say: it’s a phenomenon. Around the time shale oil cranked up, consumption (black curve) was in a recession-induced decline, leading to heady predictions of energy independence in a few years’ time. Consumption has since leveled off, and we might even expect an uptick as a reaction to lower gasoline prices. Bring back the SUV! May it as that be, the red curve is climbing, and talk of energy independence for the U.S. is not to be dismissed out of hand.

That is—until OPEC has its say. The shale oil story proceeds on two fronts: the physical front and the artificial front. Physically, shale oil remains a finite resource, as any other. I have seen mixed messages about the longevity of these “plays,” probably the balance indicating that the premium spots have been exploited most rapidly, that individual drilling sites peak and collapse on few-year timescales, and that the rapid rise we have seen may represent more of a sprint than a marathon. So I would not be surprised if the juggernaut loses steam on the back of its own success, on a decade timescale. But then we have the artificial factors (highly nonlinear human meddling) that may force a downturn in shale production by economic means. Another “artificial” influence may assert itself on the environmental front, based on flammable drinking water and the like.

In any case, I am hesitant to embrace shale oil as the “new normal,” to be increasingly exploited throughout my lifetime. Certainly you can’t convince me that any of our finite resources will be with us for the long haul, but even on the timescale of 10–20 years, I think it’s unwise to extrapolate on the basis of the new kid in town (a transient, or even drifter!).

Shale Share

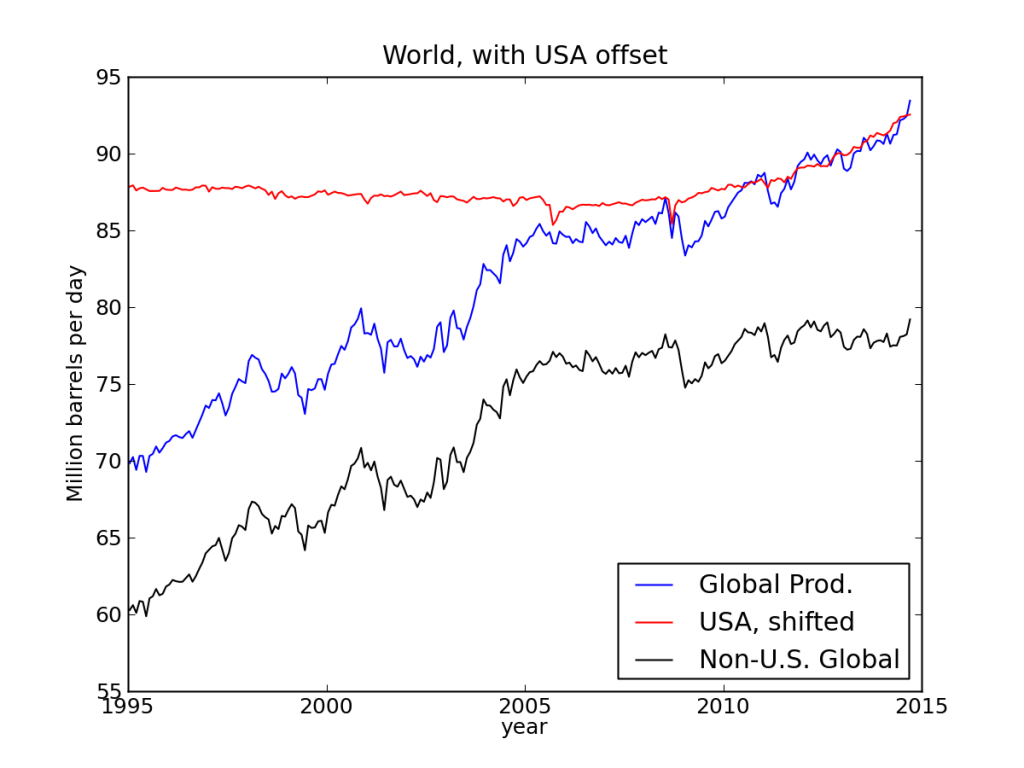

One final thing worth investigating: how much of the recent “post-plateau” growth in global oil production can be attributed to shale oil in the U.S.?

In the graph above, I have superimposed the U.S. production atop global production by adding an offset to the U.S. number so that the last few years overlap. Now the diminishing gap between the red and blue lines represents growth in the rest of the world. U.S. shale oil accounts for about 70% of the total growth since 2005. It is rather striking to behold. Global production had the characteristics of a freight train for the first ten years of this plot. Then in about 2005 it stopped abruptly (hello, plateau). The non-U.S. global production (black curve) has experienced only 20% as much growth from 2005–2015 as it did in the preceding ten-year stretch. That’s a substantial bend. Peel off the shale oil and we see that the global plateau is still very much with us—despite sustained high prices through the period.

For comparison, Saudi Arabia produced typically 9–10 million barrels per day in the 1995–2005 period, and is now edging toward 12 million bpd. While this is a commendable increase (not easy), it is not at the same scale as the U.S. increase, which now puts the U.S. back in the role of largest oil producer in the world—as it was for decades in the mid-20th Century (not a small factor in the famous prosperity of the U.S.).

Perspective

So it’s fair to say that the continued upward trend in global production post-2005 is due to the shale oil phenomenon.

What does this do to my thinking? Time. It’s added a decade or maybe two to the timescale for global peak oil. And time can be a great thing. With it, one may smartly prepare for a post-carbon world. We need time and the luxury of surplus energy to fashion a world less dependent on fossil fuels (the solution to the Energy Trap).

Some of this will happen as a matter of course. Electric cars are in a whole different place than they were ten years ago. I expect continued progress on this front—although falling short of a transformative revolution, I suspect.

But cutting against us is the sense that we have averted a crisis, so we can go back to business as usual. Investment and research into alternative energies will wane: just when we need them more than ever. Indeed, I myself do not feel the same degree of urgency that I did a few years ago, and have allowed the normal set of “distractions” to creep back in. In part, it’s just a reflection of where society at large is right now. It’s harder to draw an audience to discuss energy/resource scarcity when the headlines are in the opposite direction.

This leads to another issue on human psychology that I have been wanting to post for some time. Look for this next, when I get another break from my hat collection.

Views: 4116

Glad to see another post! More time to escape the Energy Trap is a great thing for society. Perhaps we’ll be able to get our collective…stuff together and make it out in one piece. Any chance of getting a post on Nickel Iron batteries soon?

The nickel-iron post is certainly overdue: I’ve had the cells almost a year now. But there are nuances and the jury is still out on a few aspects. So I’d best collect more data and know for sure what I want to say.

Thanks for these posts / site. I found it through the comparison of energy storage methods……..boiling down to batteries still being best. I second the request for anything on nickel iron batteries for power storage, I don’t understand why they aren’t widely adopted due to the purported far better longevity.

As for this post, peak oil, and particularly the recent cost reduction, you suggested running shale oil producers out of business. But what about …. slowing down PV adoption? Today, with incentives, the levelized cost of energy using PV for individuals with cash stored in near zero interest savings, is I believe in the 6 to 7 cents per kWh realm by my calcs.

If battery storage technology were free (it isn’t), then we could purchase electric cars for a lower price than gas cars, and, we could replace the batteries (again for free). We could install more than enough batteries at home to power the home, plus store power so that they can charge the car(s) by night. In that world, we wouldn’t need gasoline cars, and by extension, oil.

At some price point, things shift from where we really are, now, toward the scenario above. Lowering the cost of oil delays this…………it makes solar less attractive. And potentially it slows adoptions enough that during the period of the tax credit allowance, there aren’t so many people that adopted solar that we reach a tipping point where people begin installing solar to power home + car(s).

Because if we reach the place where people shift from purchasing solar for home electricity, to where they purchase larger solar for house plus car electricity, then the oil industry is stuck holding an enormous bunch of assets underground that we no longer need them to pump.

With grid tie, we can do the above now. But without grid tie and without Fed tax credits…………we need a new battery technology that gets the cost probably down to the $20/kWh realm.

So, what do you know about NiFe?

thanks again and have a great weekend…..

rt

ME

Ross, how do you imagine getting to the place where all US residences and cars can be run by solar? That scenario is wildly at odds with what Tom has said here in the past. And did you notice that he still thinks EVs will never be transformative?

I’m interested to hear what makes you think otherwise.

“The math” of the energy trap is very simple:

If the energy payback time (of wind, solar, …) is T and the growth rate is 1/T then the net energy produced is zero.

Not sure what is intended by payback time T, growth rate 1/T…………….or how one gets to zero energy produced, but…………….

IMO, the entire concept a of solar PV system having a “Number of years to pay back on investment” is bogus and misleading. The time to “pay back” for a solar power system is zero months. If you do the math on the Present Value for the savings in power bill payments, you will typically find that not only is the system entirely paid for upon installation, but typically you enjoy a large profit on the installation for the first several years.

The fact is (LBNL study and many others) that when you install a solar power system, the property value goes up by an amount equal to or greater than the cost of the system. Thus, you are not “investing” (today) in solar, you are transferring equity from a cash (liquid) instrument to a fixed asset, the solar system.

If you take out a loan, typically the loan payments are the same as the power bill payments. So you are net zero change for the term of the note, and then enjoy another 20 years or so of operational profits thereafter.

What this means is that from day one, all proceeds due to the system are profits. That means the 30% tax credit, and power bill reduction, and (for businesses) the accelerated depreciation tax incentives are all profits. Purchasing a $20k PV system often results in short term $6k (residential) to $10k (commercial) profits.

It takes 3 to 6 years to double one’s equity….. not pay back for an investment. I don’t understand why virtually everyone, including the solar sales people, all talk about time to pay back for the investment…… that idea is entirely wrong.

Welcome back!

I’m in full agreement with this article, more time is great but it doesn’t change the long term message. That said, while America may not become the crux of alternate energy research, the new oil reserve may help power the parts of the world that are. We are seeing a lot of alternate energy research out of Europe, Japan, and even China. My hope is that if the oil glut retards alternate research in the US, it will not stymy countries who still import most of their energy.

And since we are talking about new articles, I would still love a good article on Thorium Nuclear Power. You have given it just a brief overview by your own admission, and I would love to hear your take in a thorough article.

Very nice new post on something puzzling me, namely the recent drop in pump prices. If anything, it makes me more nervous when prices drop… I think it’s a long shot that we’ll make good use of any extra time which shale oil buys us, but who knows?

The other factor that should be mentioned is net energy.

Shale oil net energy is lower than that of conventional oil,

And some of the non-US portion of the plateau in later years has consisted of the replacement of depleted high-EROEI oil with lower-EROEI oil (deepwater, etc.).

So in real terms there has probably been little improvement, more of an illusion of it. The global economy has certainly not improved nearly as much as expected, which makes perfect sense when one considers those factors

It is worth to mention that oil’s value as a monopoly dictatorship for energy hungry countries is decreasing, as even more transport shifts to electricity. Electricity is more expensive but can be generated in much more ways (generally by coal). E.g. recently it was announced that in Japan there are more electric charging stations than gas stations now: http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2015-02-13/japan-has-more-car-chargers-than-gas-stations-carbon-climate

Hopefully some big shift will be if electricity will start to generate using Thorium reactors.

Had dinner with a friend in the petro industry a few nights ago. He views fracked shale oil as a “better” (from a market-reponsive POV) source of oil than the old way of doing it. When the price is right, you drill a well, you frack it, you get your quick return, and when the production declines at a good clip (as it does) you go drill the next well, as long as the price is right.

We apparently learned a lot about large-scale horizontal fracking and can now do it more efficiently than a few years ago (note that we’ve been fracking and horizontal drilling since forever, what we see now is that we’ve really good at it — stuff that was just being figured out decades ago when I was in gradual school is now ho-hum routine) and the world’s got plenty of shale deposits to (re-)explore. I’m not thrilled about this from a CO2 POV, but it’s not necessarily all bad even there — it’s not *that* cheap to drill this way, so once the Saudis lose a lot of money on their market-manipulation efforts, we’ll get a stable-ish high-ish price. What this does mean is that an economy-trashing price spike is not quite so likely as it once was. (I hope…)

Fracking is in no way good for the environment. Kevin Anderson at the Tyndall Center in England calls on the OECD nations to reduce their carbon emissions by up to 10% per year for the foreseeable future. We aren’t anywhere near this target. So increasing oil production from fracking does nothing to reduce our rate of consumption. Because of the economic paradigm of endless growth under which we live, the exponential rate at which we exploit all resources will lead to their swift decline. Oil fracking is a case in point. Tom has shown graphs of energy use that show just how much we would have to dig out of the ground just to stay even into the future. Obviously an impossibility given limits. The BAU crowd which includes just about all of us will continue on until collapse is assured. The rate of expansion of renewables is just too slow to be a possible replacement for all the energy we now use in the form of fossil fuels and besides the alternatives only produce electricity. We’re heading for a much lower energy throughput world and we should be planning for that, but we aren’t. Keep on driving, America!

You’re missing my point. For the frackers, the economics are not what we thought they were. We see rapid per-well production decline and think “bug”. For the guys financing these wells, it is a feature and allows for more predictable investments.

This has nothing to do with pollution, which is indeed a problem.

Actually – fraking is the best thing to happen to the environment since we stopped hunting sperm whales. Cheap natural gas is displacing coal in the united states – and it produce’s much more energy per unit of carbon dioxide. Plus no coal ash, mines etc. We’ve held stead on carbon dioxide concentrations, and now emit as much as we did in 1995. This is especially impressive when you realize our GDP went from $7.6 trillion to $16.7 trillion in the same time period.

“and talk of energy independence for the U.S. is not to be dismissed out of hand.”

I don’t understand the point of energy independence. Extracting fossil fuels from beneath your land doesn’t make your country energy independent, it makes it dependent upon imports of solar energy from hundreds of millions of years ago. William Catton (R.I.P. January 2015) pointed this out in his book Overshoot. I think it is a bunch of wasted talk, I mean, does our “advanced” society really understand what it is doing on a fundamental level?

Its an economic term, not a physical one.

Energy being one of the most critical commodities for trade, in general you want to be the ones supplying it, not the ones who have to buy it.

The fact that the US is current able to do that is a great boon for its economy, and gives it a lot more influence on global politics. Now how long it will last is the trillion dollar question.

I agree with cp, Extracting fossil fuels from beneath our land doesn’t make our country energy independent, it makes it dependent upon imports of solar energy from hundreds of millions of years ago. We need to explore other solutions which will truly make us independent.

Happy to see a new post! I completely agree.

Thanks for putting the shale boom in context. It’s added about 3.5 mbd. The world burns about 92 mbd.

Here is a quote from Chris Rhodes in a recent article of his titled, “Cheap Oil Does Not Mean Peak Oil is a Myth”:

“The decline in production rate from existing oil fields amounts to a loss of 3.5 million barrels a day, per year. To maintain overall supply (around 30 billion barrels per year), the equivalent of a new Saudi Arabia’s worth of production must be brought on-stream every 3 years or so.

This means that new production has to grow relentlessly, year on year, such that by 2030 (only 15 years time) we must install new production to the tune of around 5 Saudi Arabias.”

Shale oil has bought us some time but not much.

This study, which focuses on the energy expended to acquire oil more than the peak oil problem itself, might interest you:

http://www.thehillsgroup.org/

Energy in oil takes energy to acquire. Traditional EROEI calculations fail to take into account the heat loss that occurs when the energy acquired is put to work. The energy content of one gallon of oil may be 140,000 BTUs, but after heat loss only 99,400 BTU’s is available to do work for us. In 1900 the energy expended to acquire one gallon of oil was <1,000 BTUs, but it has followed a compound growth curve and is ~72,000 BTUs today. Projection of this growth curve into the future shows we reach 99,400 BTUs of energy expenditure necessary to acquire new deposits about 2030, effectively depriving us of any new oil production. The depletion of existing fields is estimated to be 5% so that won't last long either.

Up till recently we were able to expand total production at a sufficient rate to compensate for the progressively increasing energy loss in the acquisition process, but discoveries have been lagging what is necessary to keep the industrial age expanding. We may be producing more total oil, but not more net energy from oil after expending the increasing necessary energy to acquire it.

Total energy acquired in oil, after deducting heat loss, and after deducting acquisition cost is what drives creation of economic wealth (our income). The energy acquired is constant per unit acquired, the heat loss is constant at 30%, but the acquisition cost is compounding, taking us on a collision course to destroy the industrial age. Peak oil is nothing compared to the effect of the low hanging fruit principle which led us to acquire the most proximate, biggest, shallowest, purest , deposits first and leave the rest for later, only later is approaching at a compound growth rate.

Since we can't outrun this effect by increasing production fast enough (or at all), naturally the rest of the economy is under pressure to shrink. In a shrinking economy unemployed or underemployed people can not afford the high dollar price necessary to pay for the necessary and increasing expenditure of acquiring new oil deposits. So there is a Catch 22. The price necessary to fund acquisition and keep oil companies in business is too high to be paid by the end users of oil products. We are in a downward spiral that has much more to do with energy costs than to do with political manipulation of prices.

The current glut is because the oil acquired in the recent binge in tight oil and tar sands took too much energy to acquire and the price necessary to pay for it dampened demand.

One calculation in the Hill Group study shows that by 2020 the affordable price that can be born by end users of oil products will be below even the price to pay the costs of even the lowest cost producers.

The price may swing violently between too low to justify production and too high to be paid by consumers, but the end will be insufficient energy to fuel continuation of the industrial age. This is not some far off problem, but something we are experiencing now as we live out the last decade or two of an unprecedented bubble in energy consumption, wealth, and world population.

See what you think.

Without digging into the study you cite, I do catch over the figure of 72,000 BTU to produce a gallon, compared to < 1000 in days gone by. EROEI figures I have seen for oil indicate 100:1 in the golden days, dipping to 20:1 today, deepwater maybe closer to 10:1, and tar sands at 3:1. Failure to account for the "lower heating value" (30% effect) is not enough to throw any of these down to the approximately 1:1 level you imply. Still, it's a valid point that net energy is what matters, and that gross production numbers do not capture this fundamental quantity. The catch-22 you describe is a cousin to the Energy Trap idea I frequently worry about. Finally, a question that always pops into my mind when contemplating a higher-cost energy future: Where will the prosperity come from to afford this future? Prosperity in the past traces to physical resources in large part, and energy commodities as a non-trivial component of that. How will we conjure wealth absent stuff? I have heard innovation well spoken of, but that can't be the whole story.

> Where will the prosperity come from to afford this future?

Lower population?

> Prosperity in the past traces to physical resources in large part, and energy commodities as a non-trivial component of that. How will we conjure wealth absent stuff?

The sun is still sending us solar energy. A smaller population can mean more energy per person.

Your graphs are not really about oil, but all liquid fuels: they include biofuels (I guess mainly ethanol) and NGPL (and also maybe refinery “gain”), see http://www.eia.gov/oiaf/aeo/tablebrowser/#release=IEO2014&subject=5-IEO2014&table=39-IEO2014®ion=0-0&cases=Reference-2014_03_21 I think it’s a bit strange that while biofuels and NGPLs can’t be sold as oil they are often, as here, counted as oil. Moreover energy content of ethanol is about 70% of crude oil, so adding volumes together is misleading. The production of crude & condensate has increased since 2005 very slowly, much less than all liquids. Here various graphs are conveniently summarized http://peakoilbarrel.com/world-crude-oil-production-geographical-area/

Thanks for clarifying this. I knew 9 Mbpd for the U.S. around 2000 was too high, and this is likely why. I did not dig further. Nice graphs at the linked page. The non-North-America conventional is even more convincingly in plateau mode.

Tom, a few comments if I may

1) You’re plotting world total liquids. Since 2005 most of the gains in this measure have come from refinery gain, natural gas liquids and “other liquids”, which is things like biofuels. Refinery gain is just a volumetric gain, and not an increase in energy content. Natural gas liquids have about 70% of the energy content by volume of oil. If we weight these for energy, then the gains are far less impressive.

2) The platea in non-US production has only been maintained at great expense. The oil industry has been hurling huge, huge sums of money at exploration and development over the last 10-15 years, and has very little extra to show for it (see Steven Koptis’s talk for more on this: http://energypolicy.columbia.edu/events-calendar/global-oil-market-forecasting-main-approaches-key-drivers) . The large (15% or more) reductions in spend this year are going to have significant impacts in a few years. Frankly such a level of spend isn’t going to be sustainable much longer, so there’s a chance that underlying decline rates might increase. Shale growth is also likely going to plateau and perhaps decline later this year or maybe next year as the fall in rig count (which has been precipitous) kicks in. The current fall in price could potentially knock 3-4mbpd off global output, if sustained.

3) Shale is a fundamentally destabilising presence in the industry. Anything which can be ramped on/off quickly in response to price signals is likely to produce big oscillations in price, as a basic understanding of system mechanics shows (kinda like a malfunctioning PID control loop). Rapid price swings mean the industry has real difficulty planning future projects, and thus behaves conservatively, impacting future production. This cycle has happened numerous times in the oil industry, as far back as when the big gushers in the USA flooded the market, since the global economy is so fragile that another oil shock would really kick it in the balls. For the sake of market stability, shale output urgently needs regulating by a body like the Texas railroad comission, whose regulation of Texas production coincided with a period of very stable prices. The odds of this happening, however, are probably close to nil, in large part thanks to misguided faith in markets. There’s a very serious risk that the oil markets blow up in the next couple of years as a consequence.

In short I think there’s a genuine chance that your lack of worry might be perhaps unwarranted. We’ve kept things going by eating into huge amounts of capital and drilling all we can, which looks like it might be running its course. Interesting times ahead.

“Shale is a fundamentally destabilising presence in the industry. Anything which can be ramped on/off quickly in response to price signals is likely to produce big oscillations in price, as a basic understanding of system mechanics shows (kinda like a malfunctioning PID control loop).”

Why is shale a destabilizing force? It seems to me that anything which can be ramped on/off quickly would be a stabilizing force, not a destabilizing one, because it can be ramped off quickly in times of low prices, and ramped on again in times of high prices. As a result shale would decrease supply in times of low prices and thereby raise the price relative to what it would have been.

Why do you think shale is a destabilizing force?

-Tom S

Tom,

It’s a somewhat counterintuitive characteristic of systems with delays in feedback loops. If you increase how quickly you respond to a delayed feedback it can produce big swings, a bit like a malfunctioning paid control loop.

Donella meadows has a good example in a chapter in her book on thinking in systems, it’s about having to restock a car salesroom but is otherwise a similar principle. I think this section is viewable on Google books.

Anyway maybe fundamentally was a bit strong, but I’m very concerned that shales rapid on rapid off dynamics will decrease system stability.

I concur — it is a control theory problem, and I have seen this very thing in the design of a circuit to control the output of a switching power supply. Reducing the gain or blunting the initial response (with a capacitor parallel to the feedback resistor) makes the circuit stable again.

So, negative feedback then.

We had our first wakeup call in the 70s when the population was about half what it is today: the oil crisis, limits to growth, climate change, etc. We brought some time and doubled the population. If fracking buys us a decade, we will expand by yet another billion plus climate change will be that much worse. possibly more down side than up side.

Regards the drop in prices, demand may have something to do with that as much as supply.

BTW: heard from a friend that Dave Rutledge will be giving a talk at USC. Any chance of a podcast or vided?

Tony

First of all, welcome back! I missed your posts.

I think Saudi production is not so high. What was your source for these 12 million? I am not a specialist but follow oil news daily. “For comparison, Saudi Arabia produced typically 9–10 million barrels per day in the 1995–2005 period, and is now edging toward 12 million bpd.”

Check this article “Saudi Arabia increased production last year to an average 9.71 million barrels a day from 9.63 million barrels a day in 2013, according to the JODI data.”

http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2015-02-18/saudi-arabia-s-oil-exports-fell-in-2014-in-tough-year-

Tom,

Thanks for the excellent article. It’s useful to have an update on the peak oil scenario. It’s also useful to have a retrospective on what has actually occurred vs what had been predicted.

This kind of thing would be difficult Colin Campbell and ASPO to do. I’ve recently read through ASPO’s newsletters, Campbell’s papers, Aleklett’s publications, and so on. They got a few things right, and a bunch of things wrong. I suppose that’s the best that can be expected, because predicting future oil production is difficult. They got right when non-OPEC production would stop growing, and when prices would increase. They got wrong things like middle east production (which was supposed to have peaked and entered terminal decline more than 5 years ago), unconventional oil (they missed shale completely, and claimed that unconventional oil would make almost no difference), unconventional gas (they thought it would be minor), and non-OPEC conventional production after the peak (which was supposed to be declining at alarming rates by now). They got almost everything wrong when they strayed outside their area of expertise (Campbell and ASPO predicted the decline of global trade and various other effects on civilization which did not occur).

It has been difficult for them to admit this. They either maintain radio silence (Campbell and many others) or offer retrospective evaluations which omit their bad predictions and only mention the good ones. Unfortunately Campbell et al were extremely confident, staked their entire reputations on these predictions, referred to anyone who disputed their predictions as “flat earthers” or whatever else, and then ended up wrong about many things. Some other people (such as Michael Lynch and the IEA) have been more straightforward about their failures of prediction.

I just don’t know who to believe about future oil production. It doesn’t seem that anyone has a good handle on it.

-Tom S

Tom,

Michael Kumhoff (formerly of the IMF) put out an excellent working paper on some ‘possible oil futures’ the other year. It takes into account both the bits that Campbell and co missed, and also the rather spectacularly overly-optimistic predictions of groups like CERA and the eia. You can read it here: https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2012/wp12256.pdf

Some of the conclusions are eye-opening and should probably be cause for concern. Especially if you think (as I do) that standard economic production functions completely misunderstand energy (see here http://iopscience.iop.org/1367-2630/16/12/125008/article), oil in particular, and this really does blind them to how bad things might get under scarcity.

Sam

Thank you for these references. Especially enjoy Kummel

Tony

“spectacularly overly-optimistic predictions of groups like CERA and the eia”

Spectacularly over-optimistic? The EIA (at least) was a LOT closer than any peak oilers. Granted, they got prices very wrong, but they got production about right.

I just glanced through the EIA’s projections in their 2003 report. They predicted total all liquids in 2015 to be 93.9 MMbbl/day, and the actual figure was 92.1*. In comparison, ASPO’s prediction from Campbell’s “2008 Base Case” paper was 75 MMbbl/day for all liquids. Thus, it appears to me that the EIA was too high by about 1.95%, and ASPO and Campbell were too low by about 19%. This divergence between ASPO’s predictions and reality is growing wider every year (yet another “growing gap”) because all liquids have not begun declining yet.

ASPO’s predictions for gas were worse.

Granted, EIA was quite wrong about prices. However, their predictions of production were far better than peak oilers’ predictions.

Am I missing something here? What are you referring to when you say “spectacularly over-optimistic”?

-Tom S

* The figure from 93.9 MMbbl/day is taken from the EIA 2003 report, pp 38 (table 13), from the “high price” scenario for non-opec, plus the figure from pp 37 for opec. The actual figure was taken from EIA’s 2015 short term outlook, pp 2. ASPO’s projection of the same year (2015) for all liquids was gathered from the “2008 Base Case” which was reprinted in their newsletter.

Hi Tom,

“there are giant deposits (countless new Saudi-Arabia-scale fields) yet to be discovered)”

Do you have a source for this? Moreover, can they be extracted profitably?

Then there is the question of our environment. As we all know, California is turning into a desert as we speak, and the polar vortex has been coming on several years in a row now. Basically even if we found several new Saudi-Arabia, it would be suicide to burn it.

In addition, as several others have pointed out, fracked oil was never really profitable. It was enabled via debt in a completely unsustainable way. You have written before about unsustainability. Are you now saying that the world as it currently stands is sustainable?

Sorry if I’m a bit confused.

Sorry to confuse. You’ll note that the quip about several new Saudi Arabias worth of oil is in the same paragraph that says a new continent has been found hiding behind Australia. You can throw tat whole paragraph away as my attempt at humor.

Tom,

Please correct if I’ve misunderstood anything.. It’s my understanding that “Peak Oil” is the physical moment when half of the reserves have been spent. To use a metaphor, the half-way mark on the gas gauge. The accelerator pedal governs how fast the resource is used (useful metaphor) but CANNOT change how much fuel is in the tank.

New extraction technology may have jammed the accelerator forward, but no new oil is really being “discovered”.

Is it a requirement that “Peak Oil” and “Global Production Peak” occur at the same moment?

It makes sense to me to put this the other way around. The “peak” refers to the rate. That tends to happen around the halfway point, if the rate plot is symmetric. But one could imagine other scenarios where we reach peak production rate when we have more than or less than half left. While the amount in the ground may be more fundamental, the rate is more important to economies.

Glad to see a new post.

But at this point, you really need to come out with the book based on all this.

See, quite relevant today:

kimstanleyrobinson.info/w/index.php5?title=Fifty_Degrees_Below

[Edgardo:] “Economics is incorrigible. They call it the dismal science but actually it’s the happy religion.” (p.114).

“The economists should be trying to invent an honest accounting system that doesn’t keep exteriorizing costs. When you exteriorize costs onto future generations you can make any damn thing profitable, but it isn’t really true. I warn you, this will be one of the hardest things we might try. Economics is incorrigible. They call it the dismal science but actually it’s the happy religion.”

“So we have to grow up. If we were to turn into just another imperial bully and idiot, the story of history would be ruined, its best hope dashed. We have to give up the bad, give back the good. FDR described what was needed from American very aptly, in a time just as dangerous as ours: he called for a course of ‘bold and persistent experimentation.’ That’s what I plan to do also. No more empire, no more head in the sand pretending things are okay while a few rich guys wreck everything. It’s time to join the effort to invent a global civilization that we can hand off to all the children and say, ‘This will work, keep it going, make it better.’ That’s permaculture, as some people call it, and really now we have no choice; it’s either permaculture or catastrophe. Let’s choose the good fight, and work so that each generation can hand to the next one the livelihood we are given by this beautiful world.”

A long crisis – as this which US is said have now exited, but not other places jet – shall teach us important facts and experiences. Energy shall not be wasted. Renewable sources are priorities. Also are understanding and implementing the efficiency in energy production and in utilization, from national regulation, to industrial practice to family habits.

Under the crisis is easier to be sensitive and responsive, at least for being money-wise. But Tom helped to perceive that the 40% drop on the gas-station bill we had seen for a while in Italy is the result of a game among oil competitors aimed to drive one of them off the business. This is not a lucky new abundance. Then, the lessons learned on efficiency and selection of the sources are not to be dismissed for becoming obsolete. Unlike Tom noticed, I feel very uneasy to return to old habits and to ample spending. The change of mentality is the most precious result of these years, as it is quite fragile. I hope that it will not wash away. Thank you Tom to point out this for us!

“In two words: shale oil. No big surprise.” Well, except to…everyone.

Yes, resources are not infinite on Earth. No one is claiming they are physically infinite – that is a straw man argument. Like most Malthusian points of view you assume that demand will increase and increase until the resource is completely gone! Then…disaster! It is like someone eating the last can of beans on the lifeboat. In the real world this is not how it ever works. Why? Prices. Prices are simply information signals that echo around the economy and get people to change their activity. Prices increase till demand is reduced or supply increased. Usually both. So in essence, the supply of hydrocarbons is essentially infinite, not physically, but economically. For example, if oil were to reach, say, $200 per barrel, what would happen? Well certainly alternatives like electric cars, and solar panels, etc., would work to shave demand down. People would drive a lot less. Nuclear, solar, coal gasification, biofuels…Bottom line there is a peak in operation here – a cost peak, not a supply peak. Beyond the peak cost supply will always meet demand. Looking just at the U.S. demand is flat. Has been for some time. But the economy keeps growing. How is that possible? Sure the economic downturn…but also cars get more mileage, lighting is more efficient, etc. Our demand is being reduced by technology. I don’t see that changing any time soon.

Lastly, most of the shale plays have been solely in the U.S. Do you have the slightest conception of how much hydrocarbons remain in shale in the rest of the world? No, it is not infinite, but the number is VERY large, and I would say with some confidence, that at say $150 a barrel we have hundreds of years of hydrocarbons remaining.

We have entered a new world where the costs of oil is constrained at both the top and the bottom. Low prices force shale oil out of the picture, high prices bring it back in. I’d say we are going to yo-yo between around $50 a barrel to $150 a barrel for the indefinite future.

Hi Geoman

I would say that if we do have hundreds of years worth of hydrocarbons and we burn even a small fraction of them, Homo sapiens will go extinct with very high probability. That’s the other side of the thermodynamic reality which is not accounted for in neo-classical economics. :+)

Yes, price signals; yes market forces. Cheap oil scarcity will drive prices very high. This will have a negative effect on many industries. How will we afford it? Where will the prosperity come from? Because the life we know (normal to us) owes much to cheap fossil fuels, it is simply not clear the machinery will chug along if energy prices are crippling. You can play the game for a while (you cite efficiency improvements) but this doesn’t even have a factor of two left, in most cases (real physical limits).

I do agree with the yo-yo idea. Swelling prices will cause recessionary tanks in demand and price. It will be hard to construct a single narrative for what’s driving the fluctuations. But the whisper in the corner—resource limits—will always have a good point.

Dear Geoman and Tom

It may be relevant to this discussion that almost no economist was able to anticipate the Great Contraction of 2008 (see for example Reiner Kummel’s paper cited by Sam Taylor above). This is a blow to economic theory vastly more serious than if physicists hadn’t discovered the Higgs or if Eddington hadn’t verified the General Theory of Relativity. Therefore, accepting without healthy skepticism any economic hypothesis or argument such as “price theory” is committing the logical falacy ex falso quodlibet.

We might be best rewarded to stick with what we know such as thermodynamics, ecology, systems engineering and psychology and of course the data and place economic arguments on a back burner.

One bit of data I want to throw out is that the US economy has grown at an average rate of less than 1.4% since 2005 while the cost of climate related events indexed to inflation has grown at an annual rate of 7% since 1980 (source http://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/billions/time-series). At these rates all growth will be consumed by wealth destruction by 2032. I submit that this is optimistic.

At any rate I don’t suppose that price theory will be able to predice the price or availability of fossil fuels going forward with anything like the accuracy we will require.

best

Tony

A while ago you asked your readers to participate in a poll and to try to get as many friends as possible to do it as well.

We are still waiting for the results, please create a post about that.