This is part of a series of posts representing ideas from the book, Ishmael, by Daniel Quinn. I view the ideas explored in Ishmael to be so important to the world that it seems everyone should have a chance to be exposed. I hope this treatment inspires you to read the original.

This post covers Chapter TWO, when the lessons begin. Chapter 2 is presented in seven numbered subsections, beginning on page 31 of the original printing and page 33 of the 25th anniversary printing. The sections below mirror this arrangement in the book. See the launch post for notes on conventions I have adopted for this series.

1. Captive Germans

In his capacity as a scholar of captivity, Ishmael points out that it wasn’t only Jews, Gypsies, etc. who were captives of the Nazi regime in the 1930s. The entire German population was captive. Rather than terror being the operative mechanism, it was zeal, a sense of unity, and the prospect of power. It was a story that captivated people: a story of righting wrongs; of a rightful place as rulers of all humanity; of purifying humanity to the best specimens [which, as luck would have it, happened to be them!].

Plenty of Germans recognized the story immediately as “rank mythology,” but were swept by the tide of enthusiastic supporters all around them—unable to overcome the current. Anyone not bold enough to flee the country found their lives controlled by the story.

Ishmael claims that we, too, are captives of a story. Alan is knocked off balance, unaware of any such story in our culture. That’s because, Ishmael explains, the story is so pervasive in everything we do and in every interaction that it is never explicitly told in a single sitting. Bits and pieces bombard us constantly, becoming background noise that we no longer apprehend.

Alan still finds this difficult to believe, but Ishmael cautions that once aware, it will be impossible not to hear it coming in from all sides.

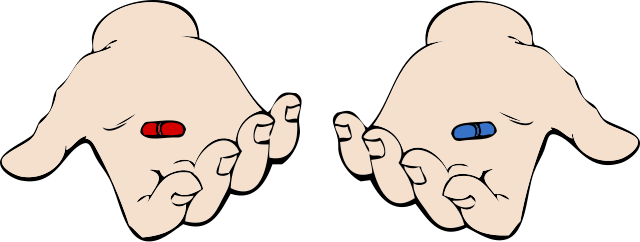

2. The Red Pill

Ishmael notes that a German unhappy with the dominant story of their culture [and possessing the means] could go somewhere else. We do not have this option. Anywhere in the world that we might go, we would still have to plug in to modernity in some way to “get fed.” Aside from scattered “savages” [and the homeless], people of this world are all enacting this story [i.e., are a part of a global market economy: use of money is a sure sign].

Ishmael pauses to warn Alan that this knowledge is irreversible. Its acquisition means nothing will be the same. The mythology of “Mother Culture” [modernity] will become ever-present. It will be harder to interact with and tolerate the people around you who drink in this tale without awareness. In their eyes, you’ll be an unrelatable weirdo: isolated and alone. [In Matrix language: are you ready to take the red pill?]

As this appears to describe Alan well enough already, he is unfazed by this warning.

3. Takers and Leavers

Likening the coming intellectual journey to travel abroad, Ishmael explains that he’s going to pack some luggage as Alan watches, thus providing some modicum of familiarity with the elements at hand. They may not make sense just now, but will become useful later.

First-up is some vocabulary. Ishmael asks Alan if the common phrase “take it or leave it” carries any loaded connotations for those who may take something vs. those who may leave it. If Ishmael were to call one group of people Takers and the other Leavers, does Alan perceive one as good and the other bad? Alan indicates that he does not.

Then, they will label people of our culture “Takers” and people of all other cultures “Leavers.” These roughly map onto what we tend to call “civilized” vs. “primitive,” but those terms carry value judgments, and Ishmael seeks a more neutral terminology.

4. A Mosaic

Ishmael states that we don’t really need a map for the journey: the route is of secondary importance. The aim is to build a mosaic of sorts, and the order of tile placement is not critical. Once enough of the pieces are in place, it will be easier to make out the picture. [Subdue the left-brain and allow the right to patiently build a holistic picture by parts.]

A preview of the picture is that we have been told fragments of the story (mythology) since birth, explaining “how things came to be this way.” Everyone knows this story, even if unaware. That, too, operates as a mosaic: it wasn’t ever told to you in one sitting, but was built in random fashion by every interaction, advertisement, movie, cartoon, school, newscast, and the like.

The mosaic to be built here will critically examine some of those pieces, and place modified versions into a new mosaic. The final picture will be quite different from what you make out now, and the exact route won’t matter tremendously. [Again, less about algorithmic logic and more about the ensemble: the symphony rather than the sequence of notes.]

5. More Vocabulary

First, “A story is a scenario interrelating man, the world, and the gods.” [The term “gods” here need not be taken literally, so don’t be put off just yet. See my opening comment on the matter.]

Second, “To enact a story is to live so as to make the story a reality.” This is what, for instance, Germans were doing in World War II: trying to realize the vision, through actions. They were trying to turn mythology into truth.

Third, “A culture is people enacting a story.” Alan still does not know what this story could be, in the case of modernity.

For now, Ishmael reassures him, all you need to know is that two main stories have been enacted by humans on Earth. One story has been enacted by Leavers for millions of years, and is still [barely] being enacted today, in scattered places. The second story is only about 10,000 years old, enacted by the Takers, and is rapidly leading toward a catastrophic end.

6. Different Stories

The culture of modernity would say that Leavers represented a very long and boring Chapter 1, and that Chapter 2—beginning with the agricultural revolution—is the far more exciting Taker part of the same story, when it becomes epic. Yes, some Leavers are left in the world as dying relics, but their part in the story is really over.

This is a false framing according to Ishmael. It is not a matter of Chapter 1 and Chapter 2 of the same story, but two entirely different stories being enacted in parallel. Each has an entirely different premise, which changes everything.

7. Modern Mythology?

The bag is packed, and the journey starts tomorrow. Ishmael assigns Alan the task of coming up with the story of modernity: “how things came to be this way.” This story serves to calm our nerves over the destruction we witness, by providing a [false] context explaining its necessity in the larger, majestic scheme.

Ishmael reminds Alan of his impression of having been lied to, all these years. The story is the lie. Alan reiterates to Ishmael that he was completely unable to elucidate the lie before, and does not see much hope in trying again now. He doubts the existence of a single, unifying story behind modernity, and is especially irked at the suggestion of a shared mythology. Ishmael counters that a mythology never seems mythological to those who share it. It’s their best explanation for how things are.

Sensing the mismatch between the assignment and pupil capabilities, Ishmael scales down the task. Every story has a beginning, middle, and end. Alan is to work out the beginning: our culture’s creation myth. Again, Alan spits back that we have no such myth, most assuredly.

Next Time

In the next installment, Chapter 3 covers the teeth-pulling exercise of extracting the beginning of our culture’s mythology from Alan. No pain, no gain.

I thank Alex Leff for looking over a draft of this post and offering valuable comments and suggestions.

Views: 2415

"once aware, it will be impossible not to hear it coming in from all sides."

Well that hits the nail right on the head.

Thank you so much for doing this Tom!

I'll use this space to offer something of a footnote about the book's framing in terms of "gods." You'd think that a staunch materialist like myself would reject the notion of gods unequivocally. Yet, it works for me.

To understand, my post on A Religion of Life might help clarify, but in brief: the wisdom of "the gods" is the wisdom of evolution in a tangled ecological context. All those genetics and gene regulations interact in mind-bogglingly complex ways in response to changing conditions and relationships—also adapting through randomness. It's rather impressive, and far beyond us. I'm fine calling that marvelous encoded wisdom fashioned over deep time "the gods." Maybe even more then happy?

Spurred by this series, I've started reading the book, staying a chapter ahead. From my personal experience, references to the gods didn't cause me pause in any way.

Thus, reading the above comment, I'm confused as to why a footnote about the term of "gods" is required? Many people worldwide have a close relationship with God or gods. I don't know yet if the book will allow them as part of the modern mythology, but science certainly has done its best to discount the existence of gods.

So is the concern that if the new mythology is to replace a rationalist view of the world, let's clarify that, oh, no, of course this doesn't mean going back to believing in god(s).

I've always felt it was possible for science and God (or gods) to co-exist, then don't need to be mutually exclusive. Does that mean that I will therefore be or remain a human supremacist?

People on both ends of the spectrum can be miffed by "gods." Staunch monotheists might find it offensive and "retro" to say "gods" not "God," while staunch atheists might be allergic to any hint of spiritual, mythical basis in a story. Certainly in the academic world, one never hears reference to the gods, unless in a joking manner. I wanted to build a bit of a bridge in particular to those individuals who reject the notion of gods as "beneath" us, or childish, or primitive, or whatever. It can be a great shorthand for fabulous emergent complexity beyond our brains to comprehend.

Do you remember the old movie, "The Gods Must be Crazy"?

Seems quite apt.

Haven't seen it in ages, but I remember loving it.

I offer some corrections:

"Ishmael points out that it wasn’t only [immigrants] who were captives of the [MAGA] regime in the [2020s]. The entire [American] population was captive. Rather than terror being the operative mechanism, it was zeal, a sense of unity, and the prospect of power. It was a story that captivated people: a story of righting wrongs; of a rightful place as [the greatest nation ever on Earth]…"

There. I feel better now. Can't happen here, obviously.