This is part of a series of posts representing ideas from the book, Ishmael, by Daniel Quinn. I view the ideas explored in Ishmael to be so important to the world that it seems everyone should have a chance to be exposed. I hope this treatment inspires you to read the original.

This post covers Chapter THREE, when Ishmael extracts the beginning of the Taker story from Alan. Chapter 3 is presented in eight numbered subsections, beginning on page 47 of the original printing and page 51 of the 25th anniversary printing. The sections below mirror this arrangement in the book. See the launch post for notes on conventions I have adopted for this series.

1. Zero Mythology!

Having provided a tape recorder, Ishmael goads Alan into capturing audio of his culture’s “folktales.” Alan again vehemently denies that any mythological aspect will attach to his account of the Taker story. He acknowledges that our understanding is incomplete, and subject to revision—but definitely not mythical.

Roll the tape…

2. Standard Cosmology

Alan recounts the standard (approximate; broad-brush) tale. The universe began in a Big Bang 14 billion years ago [I’m inserting today’s numbers and some other minor details]. About 4.6 billion years ago, the sun formed in our (much older) galaxy out of primordial gas and a pinch of dust from previous generations of stars. Earth and other planets soon coalesced out of this stardust around our sun. Once the heat of formation and bombardments tapered off, life pulled itself out of the soup about 4 billion years ago.

Microbes complexified to slimes, followed by the emergence of plants, fish, arthropods, amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals. Primates branched out, “and finally man appeared”—roughly 3 million years ago. And that’s it.

Ishmael challenged Alan’s belief that his story was not a myth. Alan swore it wasn’t, and after being told to listen to the tape again defended its status as uncontroversial for any middle-school science textbook. Yes, Ishmael, agreed: it is fully accepted by your culture, of course.

Alan insisted that it was “a factual account.” And this is important: Ishmael acknowledged that it was “full of facts,” but that “their arrangement [and emphasis] is purely mythical.” So, Alan peppered Ishmael with questions about whether evolution is a myth: no; that humans didn’t evolve: no. On playing the tape again, Alan picked up on the word “appeared,” and wondered if Ishmael was picking on the semantics of not using “evolved.” No: nothing as pedantic as that.

Ishmael observes that Mother Culture has been very successful in its ear-whispering campaign, stamping out any awareness of a mythological angle to our story.

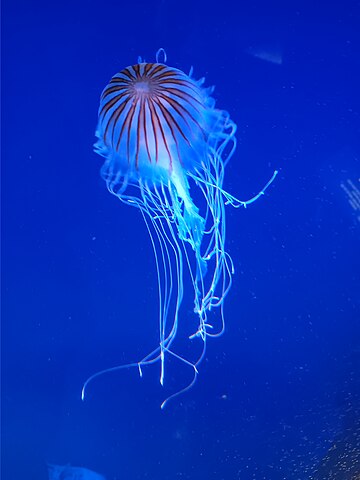

3. The Jellyfish Version

To help illustrate, Ishmael offers a parable: a similar explanation from a jellyfish 500 Myr ago—who also denies the presence of any mythological elements in its account. The jellyfish story runs much the same as Alan’s did, but ends at an earlier point, culminating in the triumphant arrival of jellyfish on Earth.

4. Mythology, Dammit!

Alan accuses Ishmael of being unfair—clearly making some sort of point, but not easily able to identify what it was. In any case, it unsettled him. Clearly the jellyfish was not acknowledging (or aware of) the fact that there was much more [and better!] to come. Alan maintains that in his case, it is correct: humans are the end of creation: the pinnacle, and the whole point of evolution: “nothing left to create.” This is the common attitude within modernity: often unspoken but sometimes quite explicit in religious teachings, where the entire universe is here for us.

Everyone in your culture knows that the world was not created for jellyfish or salmon or iguanas or gorillas. It was created for man.

Alan agrees, to which Ishmael again challenges such a belief as being anything other than myth. Did cosmology and evolution grind to a halt when humans arrived? If this were true, it would not be hard to find many lines of supporting evidence to be added to the facts scaffolding the story. So, if it is not a fact that humans are the endpoint, or purpose of it all, then what is it?

Alan, through a grimace, admits “Incredibly enough, it’s a myth.”

5. The Big Spin

Noting that Alan’s story pulled focus from the universe as a whole to this one planet, Ishmael asks: why? The appearance of humans becomes the banner event, after which the rest of the cosmos is of little continuing interest. Earth itself is merely a machine-like substrate supporting humans. Ishmael asks Alan—having now admitted a mythological foundation to the story—to speak in terms of the intentions of the gods, in a figurative sense [see earlier footnote/comment about a materialist interpretation of “gods”].

Alan says that the gods created the universe, Sun, and Earth for humans “to have a hunk of dirt to stand on.” Under this premise, Ishmael notes, humans must be a species of particular importance in the cosmos. But the story thus far does not reveal what destiny the gods have in mind for humans.

6. The Premise

Every story is “the working out of a premise.” The Leaver premise is different than the Taker premise. The entire Taker history, from triumphs to tragedies, is the playing-out of this premise.

Ishmael has a hell of a time squeezing it out of Alan, but eventually:

The world was made for man […] then it belongs to us, and we can do what we damn well please with it.

Indeed, we speak of our planet, our environment, and even our wildlife. That’s what mythology looks like: not facts, but an interpretive wrapping. [To be clear, it is not shameful to have a mythology: that’s always been part of being human. It’s how a particular mythology interacts with the more-than-human world that ends up mattering.]

7. Why So Screwy?

Connecting this anthropocentric premise to the goal of discovering what our story says about how things came to be this way, Ishmael asks if the world would be in its present [dire] state if it had been made for jellyfish? No: so perhaps this premise conveniently allows us to blame the incompetent gods for creating the mess we’re in.

8. On to the Middle

Alan’s assignment: come up with the middle part of the story. Alan predicts it will mimic the style of a Nova show.

Next Time

In the next installment, Chapter 4 gets Alan’s account of Taker mythology about the middle part of our story. Now that humans are here, what happens?

I thank Alex Leff for looking over a draft of this post and offering valuable comments and suggestions.

Views: 2106

3.3 It's been about two decades, but I can *still* remember the jaw-drop, gut-punch sensation I felt when I first read "…but finally jellyfish appeared!" though I was definitely more excited than Alan to connect those particular dots. It was a comeuppance I hadn't realized I was anticipating. And then watching the arrogant human-supremacist dominoes begin to fall from there…. I really enjoy the flow of these particular mosaic pieces and, well, it was extra-satisfying to read this after coming across techno-optimist nonsense about the nobility of human space colonization in a place I wasn't expecting today.

A minor point from a subtly different corner of our Taker culture: What's a 'Nova' show?

I remember that it was also about here in the book that I began to realise Quinn was giving me a view of fundamental things that was radically and very consequentially new to me.

Nova is a PBS science show on TV in the U.S.: https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/

The extent of my religious upbringing (or lack thereof) when I was a child was a cartoon my beloved Dad had pinned to his bulletin board showing two fish in a fishbowl; one says to the other, "So if there's no God then who changes the water?"

So from an early age I was comfortable with the concept of being just another animal species that makes up mythology to explain things that are beyond our knowledge.

I did not construe the cartoon as, aren't fish stupid, they just can't conceive that we — their "gods" — change the water. Nor did I think it meant that there are some "higher being(s)" with human-like intent who are changing our water, so to speak*. Rather, to me it meant that we're just another animal species and, like the fish analogy (though maybe not — see https://www.ox.ac.uk/news/2016-06-07-fish-can-recognise-human-faces-new-research-shows and https://www.discovermagazine.com/planet-earth/wild-fish-can-recognize-individual-people-and-maybe-even-human-faces), that there are things beyond human comprehension.

Of course, I don't know if that was exactly what the cartoonist intended but that's what it always meant to me (and now I'm pushing 70).

* Or, perhaps, "We'll make great pets." (Porno for Pyros, "Pets", lyrics at https://janesaddiction.org/songs/porno-for-pyros/pets/) 🙂