Showing my age a bit, a young Chris Rock in a 1988 movie amusingly asks: “How much for one rib?” Given that the crafting of a single protein plays a central role in this post, and ribs are a source of protein, the association was too much for me to pass up in the title.

I’ve pointed out before that our most elaborate inventions absolutely pale in comparison to even the simplest form of Life. Our gizmos can’t self-replicate, heal wounds, feed themselves, stave off pathogens, or self-evolve. Even though both gadgets and Life appear to be based on atoms and the same fundamental interactions, the level of complexity in Life is far beyond our means to create. At best, we bootstrap and copy.

To make the point, we’ll embark on a well-funded thought experiment that is able to assemble the top talent from around the world in a team given one mission: generate the genetic coding that would carry out a specific novel function by way of synthesizing a novel protein specific to that task. We stipulate a novel function that hasn’t arisen in any lifeform, otherwise the open-book (Google-connected) nature of this test would instantly result in “cheating” off a billion-year heritage.

Let’s see how they do.

Major Caveat

The whole premise of this thought experiment suffers a major flaw, in that the world’s experts could not be tricked into pursuing such a mission. They know better, for all the reasons sketched below (and more). So, I want to be clear that this post isn’t at all “hey, look how dumb the experts are” as much as “we don’t possess the most rudimentary capability next to biological evolution.” The real experts are not in disagreement.

Basic Idea

Getting on with the fantasy, I should first provide a crude primer on the crucial role of proteins, to my limited knowledge. Proteins provide specialized structures, defense, communication, mobility, and facilitation of chemical reactions (catalysis). For the purposes of this post, I’ll focus on the last function, in which case we call the proteins enzymes. These magical beasts promote and accelerate reactions that would either proceed too slowly or not happen at all on energetic grounds without substantial assistance. Some enzymes break down certain molecules—like lactose, for instance. Other enzymes build molecules out of parts, which I select here as the main example for the post. Similar arguments would apply to all other functions as well.

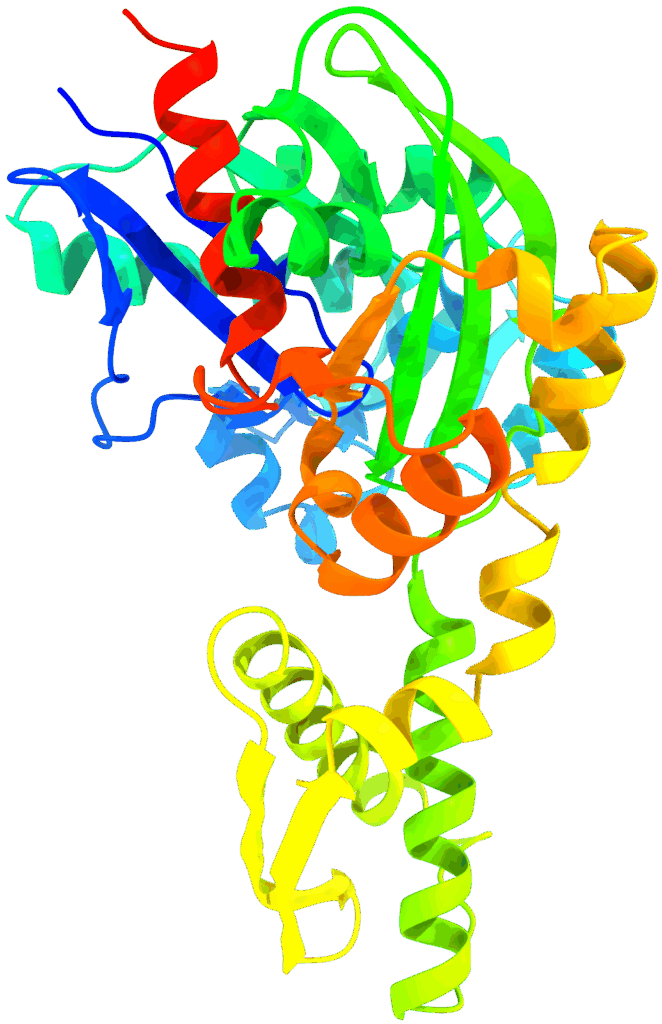

Proteins achieve their primary functions based on shape (how the long polypeptide chains fold and curl) and electrostatic affinities of their exposed surfaces. The building enzymes are configured to attract certain molecules like puzzle pieces fitting into customized pockets of the perfect shape and size. A new molecule is synthesized by the protein grabbing two (or more) different components out of the cytoplasm, holding them in the appropriate orientation relative to each other, and putting them next to each other so that they can attach.

In this sense, enzyme proteins act like a romantic matchmaking service: identifying compatible pieces who might otherwise never find each other (or if they did, might be too shy to talk to each other) and putting them together in a happy couple. Other enzymes, of course, trigger divorce.

DNA contains genes, and genes perform a similar trick to proteins, although in an unbelievably-elaborate multi-stage dance. Particular 3-letter chunks of …GATTACACCAGACTA… are matched to amino acids (via transfer RNA adapters), so that they build complex proteins by sitting amino acids in chairs right next to each other until they kiss. We’ve impressively reverse-engineered DNA/RNA to this point: we can appreciate how they build the proteins they do, and we can appreciate how a particular protein selects particular components and puts them together (all physics-based). Likewise, I can understand how a symphony works by watching the bowstrings and puffs while hearing the unique instrument contributions. Asking me to compose and play a symphony from scratch is an entirely different story. Bring ear plugs.

Ground Rules

Okay, so we’re going to ask our imaginary crack team of scientists to design a stretch of DNA (constrained to its four base pair “letters”) capable of assembling a novel enzymatic protein (constrained to a small set of amino acid building blocks) not yet encountered in any biological context. Maybe its job is to stick ammonia onto methane. But this is a poor example, because Life already figured this one out. To steer well clear of what Life has already conjured, let’s have it attach yellowcake (H8N2O7U2) onto dipotassium titanium hexafuoride (F6K2Ti). I don’t know: these may not be “stickable,” but the exact pairing is not crucial to define in this thought experiment: something could work that Life has not stumbled upon or needed yet. We just want two molecules that current protein libraries don’t assemble to prevent cheating off Life. That way, we can make the test “open book” without worry.

Actually, scratch that prescriptive approach. To be more Life-relevant, we start by defining a novel function the cell is to accomplish. Maybe the cell needs to import aluminum atoms through the cell wall, so we need to come up with a molecule (or set of molecules) that would accomplish that targeted task—and therefore require the protein(s) that could synthesize that molecule(s) out of available materials. This is probably already too complex as an example, requiring multiple interacting genes. But you get the point: we want a particular functional outcome at the cellular level that requires a particular molecule/structure that in turn requires a specialized protein (or set of them) that requires a stretch of DNA to carry out the protein synthesis. This is what Life does: establishes bridges across the multiple gaps between final function and construction of the various assemblies that execute the plan.

No Go

Life has done this trick millions of times. It’s old hat. How will our well-paid team do on just one example?

Well, the task would be hopeless to design based on knowledge/understanding/brain-work (which is why no experts would cooperate in real life). The first major hurdle is figuring out what novel structure would carry out the intended task. The next barrier is how to assemble that structure out of available compounds. Then one needs to define what relative orientation of the two components would stick in such a way as to accomplish the desired function. We still need to devise a new protein structure that would attach to some part of component A (in an appropriate place) and the same for component B. Next, it has to twist in the right way—possibly triggered by the successful acquisition of A and B—so-as to stick them together in a compatible way. Of course, this protein operates under the serious constraint of having to use a restricted menu of available amino acids as its building blocks.

It’s pretty awesome what Life achieves! And I’ve glossed over tons of intricate twists in the story. If reading about the process for the first time as part of a sci-fi novel, I wouldn’t believe it to be possible: outlandish fantasy.

Once down to amino acid configurations, figuring out the DNA sequence to assemble those amino acids is basically already in hand. But even this is a way of cheating: bootstrapping off an already wildly-complex mechanism for synthesizing proteins. If relying on basic first-principles understanding, just designing that one step would be a a hundred bridges too far.

That’s Just One

Consider that this unachievable task is just to build one protein. Billions of dollars couldn’t do it. All the king’s horses and all the king’s “men”…

Now, humans are based on 20,000–25,000 genes. The range of uncertainty alone tells us something, right? Even a “simple” amoeba has 13,000–15,000 genes.

If we can’t make a single gene to construct a novel protein that catalyzes a particular reaction to create a molecule that carries out a specific task, think how impossibly hard it would be to make thousands from scratch! Granted, each would not be as hard as the first, but new challenges would continually crop up all along the way.

And They Interact

Of course, the task of creating a viable living being from scratch is not as “simple” as churning through thousands of novel genes. The functions of the proteins interact with each other. The products of the proteins interact. The environment interacts. Other organisms interact. Just consider that two of your novel proteins might stick to each other unintentionally, incapacitating both.

I’m having trouble even finding verbiage that remotely captures how enormous this complexity becomes. Every gene serves some adaptive purpose that has been worked out by long trial in the full, unredacted context of all these interactions. The number of relevant interactions between ten thousand proteins and their products easily stretches into the millions. It would be impossible for us to anticipate all the goofy interactions that take place in a real system of this complexity if starting from a blank slate—many of which would cripple or kill the resulting organism, resulting in non-viability.

Basically, for every intended consequence (function, via proteins), we’ll find numerous unintended consequences. These cascade and self-amplify as complexity increases. Only patient trial and error—not brains—can sort it all out, step by step.

Regulating

As if not hard enough already, only 2% of DNA is dedicated to genes (protein-coding). The vast majority contributes to regulation of those genes. If the cell was constantly running full-throttle, churning out every protein in its library willy-nilly, it would be absolute pandemonium (and not a viable lifeform; the stomach wouldn’t know what to do with all those retinal cells!). It would be like every tool in a giant hardware store performing “work” on a car at the same time. Nothing good comes of that. Get those saws away from the vacuum hoses!

The cell needs to selectively turn on or off specific combinations of protein generation depending on what it’s trying to accomplish in that place and time. This is a sort of decision-tree programming. How does the cell know when to seek food? How does it know when to initiate mitosis? How does it know when to slow metabolism? I don’t know enough to fill out the thousands of questions a microbe must answer based on its varying circumstances—let alone the correct answers or how to program them (they’re geniuses, I tell you!). But all of this “knowledge” is written in DNA, mediated by various sensors and structures that the DNA knows how to build and maintain. The complexity is truly staggering, but that’s what billions of years of patient and open-ended experimentation gets you. Don’t foolishly try to fit it in your brain.

Thus, even if we were able to generate DNA sequences capable of coding tens of thousands of proteins, each with a specific functional duty that in some cases is a few steps removed (e.g., through the synthesized products of the proteins), and each interacting in compatible ways, the next step of regulating all this activity is itself immensely difficult and well beyond our capability.

Absolutely Hopeless

To summarize, the best talent in the world could not concoct a genetic sequence to make a single novel molecule in service of a particular functional goal. This is just one of over ten thousand genes needed for something like an amoeba. The genes and their protein products and the products of the protein products interact with each other and with the external world (including DNA/proteins/products in other organisms). All of this is regulated by genetic code that dwarfs the protein coding portions. And the result is a viable lifeform capable of self-replication, metabolism, food acquisition, evasion, repair, defense, and lots more, I’m sure—all in relation to many other organisms being their own irrepressibly-quirky selves.

Thus, I claim there’s no way that we could replicate even the barest of Life’s achievements. Our artificial gadgets and machines—no matter how sophisticated they appear to us and how proud we are to have invented them—are light years away from even the simplest living being. (They tend to employ just a few straightforward tricks, brute-force replicated millions of times.) Even working backwards surrounded by complete and functioning templates, we’re scrambling to understand the most basic aspects of Life.

Yet, we find that we do possess the asymmetric power to destroy life and permanently erase species from the planet. What took millions (and really billions) of years to hone is undone in decades. At least that’s something to make us proud.

What Doesn’t Follow

Clearly, I believe Life to be amazing and that it’s far, far, far beyond our capabilities to create anything even remotely as incredible. Keep that in mind when I say that I also believe living beings to be arrangements of atoms adapted to the universe, using the same physics everything else does, including our pathetic machines. To me, it’s all the more amazing that Life managed to solve this enormous list of difficult problems employing the same atoms and physics as everything else: just lying around and available for use.

I mean, we can at least catch glimpses of how atomic arrangements and electromagnetic interactions conspire to store information, build proteins, regulate protein activation, and use protein shapes to catalyze reactions—all without requiring new physics. We immediately get lost in complexity after that, though. All the same, we can appreciate the presence of the complexity, as the receipts are present in the form of DNA coding and the menagerie of resultant functional proteins. It’s just that interactions quickly overwhelm our cognitive capabilities, even when allowed to write stuff down [the subject of next week’s post].

The goal, here, is deep humility, a form of awe, and a sense of universal connectedness. As stupendously breathtaking as Life is, everything uses the same stuff and the same rules. We share a deep kinship with all matter, then. We are as dirt, and if that’s not grounding, I’m not sure what would be.

I thank Nigel Goldenfeld for taking a look at a draft and offering useful comments as an expert in biophysics.

Views: 2956

"You can study a butterfly in minute detail, but you cannot create a butterfly"

Japanese wisdom

As a bench chemist of half a century making a wide variety of chemicals for various projects I always felt humble when I look at the reactions enzymes catalyze.

If we could design (or by accelerating the evolutionary process), novel enzymes to break the carbon-carbon bonds of polyethylene (polystyrene, PET) chains, it will be a great service to the future life. I have no doubt that it will happen after we leave the stage.

There is no doubt that, to our pathetically simple minds, life seems awesome. Yet that awesomeness feeling is just the interaction of atoms that make up our brains (at least for those who get that awesomeness feeling). I guess that the same can be said for the feeling of deep kinship to all those accumulations of atoms that we call life.

I absolutely love that a tawny owl 'fits' into its woodland habitat with the same degree of specificity as an enzyme fits its substrate. I love that 'echo' on different levels of the hierarchy of life.

A beautiful connection: yes! The web of Life is intricately jigsaw-puzzle molded onto itself in many dimensions at once (vs. paltry 2-D of actual jigsaw puzzle). Inseparable; all one incredible material expression (integrating rock and sun and water and air as well).

Thanks for that amazing bit of enrichment!

@tmurphy

What a lovely thought experiment, Thank you!

Prompted by your article, while (re)reading part of Ball's excellent book "How Life Works", I had this corollary thought: – To grasp (or even frame) a vastly complex system such that you and he describe, our linear, sequential/phonetic language might not be compatible to a pictorial/diagrammatic/hieroglyphic one. Let me explain what I mean with an example a noted orientalist once told me.

Inscriptions on a single paper fan can hold the content of the book "Art of War" by Sun-Tze, albeit in a condensed form. The one mentioned was carved exquisitely into an ivory fan. Sadly, my meat-brain was not equal to the task of really grasping the pictorial rules for the condensation. Still, if classical Chinese had this ability to enfold and condense information, it had to do it in a fairly lossless way. I imagine simple lists could not be amenable to such treatment, but complex contextual information could truly 'come alive' this way. Thus, both the coding and the interpretation was a refined form of ancient art.

Meanwhile, scholars were available to interpret the condensed form contextually also reading the inter-relations (e.g. pictograms related to each other in successively larger nested patches). This way, they were able to expand and replicate the original content of the entire book. To me the whole process is somehow evocative of the DNA/Histones-RNA-Polypeptide/Enzymes circle/cycle. Imagine unfolding the fan at the right place like the RNA polymerase does the DNA/Chromatin for 'Transcription' and then the scholar reading it not unlike a Rybosome does for the 'Translation'.

And for how this might also work in recursively smaller units, that much I understand that even a single pictogram can be built in a nested fashion and have nested meanings, albeit regulated by the accumulation of customs. Again, not unlike how RNA-s regulate the process of life, while themselves are smaller pieces of a common code.

This calls to mind the power of metaphorical thinking: grasping a multi-faceted idea all at once, in a flash of insight/recognition.

Can the asymmetrical nature of things being easier to destroy than create be ascribed to the universe's disposition towards entropy? All sorts of crazy things are happening in the universe at any moment, supernovas are going off, asteroids are colliding with planets, stars are being shredded by black holes, etc.

It seems that the structure and mechanisms of life being orders of magnitude beyond our capacity to understand causes all of our attempts at controlling or managing it to be defacto expressions of entropy. We think that we're being clever and creating order and control in our little world, but it is actually the opposite, and the human enterprise writ-large is a giant entropy pump. There's no iteration of turning the earth into an island and human amusement park that would work out differently in practice.

Now, while I am saddened by all of the extinctions currently happening, there is something simultaneously hopeful to me about the resilience of life and the patience of evolution. There have been mass-extinction events in the past, but life and evolution trucked on and ecological niches no longer occupied by one form of life became fertile ground for new evolutionary experiments and the emergence of new interesting things. The canvas can be washed, but the art never stops.

What new iterations of life will evolution come up with a few million years from now? I'll bet that there will be some really cool organisms and ecological arrangements that our meat-brains could never hope to imagine.

I tend to shy away from entropy arguments, as in order to apply the Second Law one must count microstates into which energy can "tuck," which often breaks down in macroscopic comparisons. But it would indeed apply to smashing a rock to powder: many more surface vibrational modes opened up.

Short of (and probably actually including) nuclear annihilation, I have little doubt that Life will find a way (make that millions of ways at once) to thrive. Among other disruptions, in the last short while we've mixed up ecological domains around the world by introducing "invasives" everywhere. It's like shaking the etch-a-sketch or removing all the cages at a zoo. It's going to take millions of years to recover from that shock. The Community of Life has seldom been as stressed as it is in this moment. Yet, Life will march along as only it can do.

Entropy would apply to every fossil fire that we've ever burned, would it not?

I remember a study that indicated that technological energy consumption would create habitability constraints within pretty short order, circa ~1,000 (earth) years. I think that I've heard you speak similarly, possibly in your physics text book, that waste heat + exponential growth would eventually hit hard thermodynamic limits (death by entropy). Of course, to get to that point, one would assume a substantial amount of energy consumption has already occurred at civilizational scale to build up the technological infrastructure, and therefore the accompanying environmental impacts from material extraction and dissipative pollution can be inferred, so ecological and other problems will crop up first. Probably such a planet already has substantial energy imbalance, like ours, having changed the chemistry of the atmosphere and the physics of climate forcing with dissipative waste. But in some ways there is more useful energy within the system, as far as super-storms are concerned, not exactly entropy. Yet, we have less burnable fossils (potential useful energy) than we used to. Bill Rees had an interesting paper on cities being thermodynamic dead-ends that speaks to this issue: https://www.docdroid.net/ZPtk0qA/why-large-cities-wont-survive-the-twenty-first-century-pdf

I would say at least that technological civilizations are highly dubious on thermodynamic grounds if nothing else, capable of lasting for only a short stint. Entropy seems to be part of the story, but energy imbalance is perhaps a more encompassing term since there are multiple dynamics at play. Though I defer to you in physics and am eager to hear more about microstates.

As for nuclear annihilation, I bet that tardigrades would still survive. And yes, it will take millions of years to recover, I think the average consensus is ~6 million years to wash away the pollution from the last 200 years of industrialism.

Many years ago I heard the metaphor (from memory); nature builds a molecule like building a church one brick at the time. Humans put a stick of dynamite under a pile of bricks and hope they will fall down in the form of a church. And sometimes they do!

Hi Alex et al

Given your mention of life, entropy and microstates, I thought you might be interested to read the three recent “biocosmology” papers of Cortes, Kauffman, Liddle and Smolin. There are links here:

https://biocosmology.earth/

https://arxiv.org/abs/2204.09378

https://arxiv.org/abs/2204.09379

https://arxiv.org/abs/2204.14115

There’s also a click-bait write-up:

https://www.discovermagazine.com/the-sciences/how-the-new-science-of-biocosmology-redefines-our-understanding-of-life

It could all be complete nonsense for all I know, but I found them interesting (the parts I managed to digest). They contain quite a few “flights-of-fancy” (the idea of a possible link between the emergence of life and dark energy around 4 billion years ago takes the cake!!!). Kauffman, in particular, is well known for putting a lot of highly speculative stuff out there. But I still reckon they’re worth a look 🙂

So for reference, the estimate that I have is about 30 zetajoules of human energy use since 1850, 83% of which occurred since 1950. While Chicxulub impact is estimated at ~300 ZJ of kinetic energy. So we're talking about 1/10th of Chicxulub kinetic energy, not de minimis, used in a variety of destructive ways over a geologic blip of time. Major system changes are implied.

Thanks for the analysis and paper link, Alex. Very interesting. Billions of people churning through fossil fuels is certainly a recipe for disaster.

Axel Kleidon is another physicist that appears do a decent job of analysing what is going on on Earth from the perspective of energy and entropy flows, including the impact of humanity on the Earth’s physics.

He has a book (“Thermodynamic Foundations of the Earth System”) plus two comprehensive reviews that might be of interest:

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1571064524001349

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1571064510001107

The biocosmology papers I mentioned are certainly highly speculative, but I wouldn’t place them in the quantum woo category. They contain a fair bit of heavy-duty scientific analysis (with a focus on entropic considerations). If nothing else, they really bring home just how amazingly complex, integrated and innovative life is. I found the “Theory of the Adjacent Possible” (TAP) stuff contained within them fascinating (lots of explosive hockey stick-shaped curves). It renewed my faith that life “will find a way”. I think they are worth the effort for interested readers, even if parts may grate.

So Einstein's famous equation was E=MC2, but he also said that "everything is energy". E=E should be the more famous equation because E=MC2 is easy to derive from E=E, closer to first principles.

If we're thinking in terms of everything as energy and energy flows, then how could a civilization using thousands of terawatts of energy in a 200 year period not result in thermodynamic disequilibration and planetary energy state change? That much energy throughout at that velocity… Think of that converted to kinetic energy and it's kind of like an asteroid impact. No wonder we kicked off a six mass extinction. https://www.google.com/amp/s/phys.org/news/2024-09-advanced-civilizations-overheat-planets-years.amp

I think this line of thinking is less far out than dark energy causing the emergence of life, which I doubt that I could make heads or tails of. Sounds a bit like quantum woo.