Almost as if done deliberately to demonstrate mental incapacity, I recently found myself making a connection that was staring me in the face for years but that I never recognized. Surely, scads more sit waiting in plain view, yet will never be smoked by me as long as I live.

In this case, several overt clues tried waving it in my face, but I remained oblivious. I feel like my former best-buddy cat who was always mesmerized by water, never tiring of watching it slosh, splash, and splatter. My wife and I once took the cat(s) on a reluctant car trip passing along the coast of northern California. The road came right up on the beach, and I stopped with the idea that I would show the ocean to him, which would surely captivate his attention and blow his mind. We were so close that the ocean and waves dumping on the beach were almost all that could be seen out the window. I held him up to take in the sight, but in his squirming state—questioning what new cruelty I was subjecting him to on top of this already-heinous and interminable car ride—he somehow managed to completely fail in ever noticing the ocean. But it was right there in front of him! You can lead a cat to water…

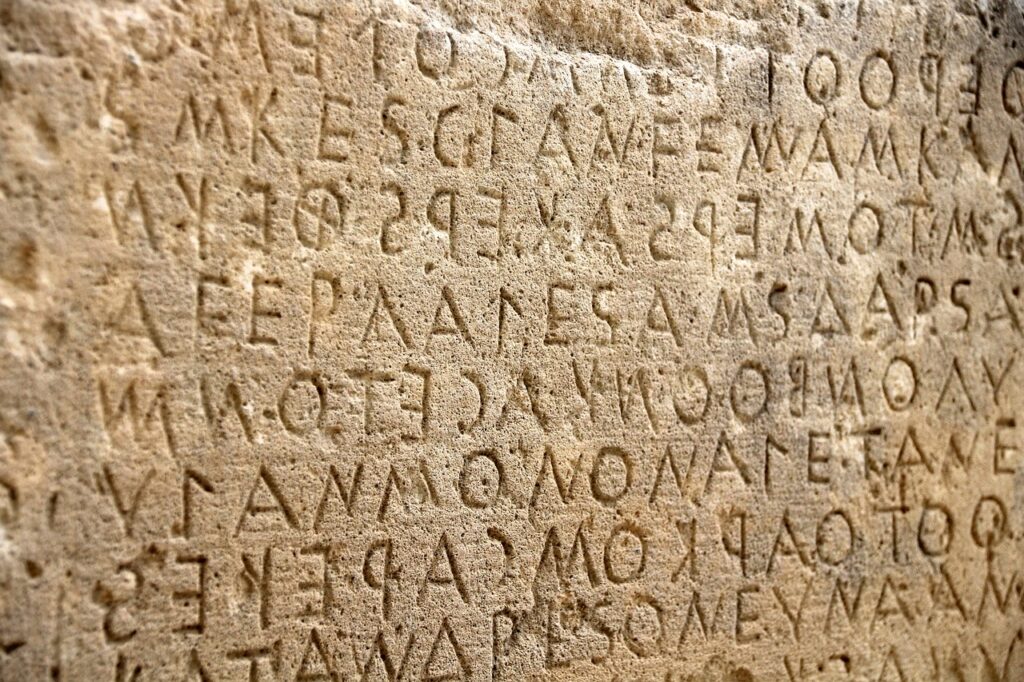

Oh—I should get to the point? A couple weeks back, the post on Spare Capacity mentioned the outsized detrimental impact written language has had. I know. Here I am still using it. But like my cat, I failed to notice what kept filling my field of vision.

Continue readingViews: 725