Okay, we needed to go on a long two-post detour in order to better understand how manifestly-imperfect mental models trap many of us in a self-centered dualistic mindset, and how we might recognize the pattern and move past it. For some, it may be tempting to focus on the division between humans and animals as the crux of dualism, but the more fundamental divide as articulated by DayKart [my gesture of disrespect] is between mind and body (matter). As long as we hold minds to be transcendent phenomena apart from matter and proclaim without evidence that “mind” could not possibly derive entirely from vanilla physics and atoms, we risk elevating ourselves to holy status—justifying the savaging of mother Earth as a collection of commodified resources. Perhaps more importantly, there’s also a very good chance it’s just plain wrong.

To be clear, I am not claiming to have the right answer. No one can (or should) make such a claim. But I will make the case for what it seems the universe is trying to tell us. It’s not necessarily the most appealing framework (even for me), but what is that to the universe?

Relatedly, here’s what I think really gets the goat of those who cringe at the suggestion that mind is not apart from matter, and that it is in fact “just” an arrangement of matter: such a stance would seem to relegate us and all living beings to mere “machines,” echoing DayKart’s disregard for animals as unfeeling automata. As vile as the implications were in his case (vivisections), why “demote” not only animals but ourselves (gasp) to similar lowly status? It’s demeaning—if one derives meaning from a sense of supremacy, as many in our culture do. If we (and animals) were just machines, all sorts of atrocities would seem to become fair play, and we would wish to avoid this at all costs.

We need to pause and take a breath, here. The reaction spelled out above is burdened with hasty reflex and all sorts of mental-model baggage (and only makes any sense in a recalcitrant dualist framing). We’ll have to unpack all this, slowly. We’ll eventually get there—not all in this post—but for now I’ll just point out that it is abundantly clear to us (and is also true, I would say) that we and other living beings are far more amazing than any machine we might imagine when restricting the comparison to our technological gizmos.

We’ll revisit the central “machine” objection a few times in posts to come, but for this post it’s time to outline basic metaphysical options to help guide our discussion.

The Options

As the central split of dualism is between mind and matter, four basic options present themselves:

- Both exist, as different “substances” or on separate/parallel planes (whatever that means);

- Everything is mind: matter is a figment/product of imagination;

- Everything is matter: mind is generated by normal matter interacting via physics;

- Neither exist (leaving nothing to write about: poof!).

Unfortunately, the cultural prevalence of dualism is older than the languages in common use today, and is thus deeply integrated into language (itself a mental model). Dualism underwrites sentence structure (subject/object); first/third person (pervasive focus on “I,” “me,” etc.); objectification via noun emphasis; and animate/inanimate divides (reflected in pronouns). Words and their grammar are all crude and clunky representations—not the reality they attempt to capture. Language conventions stealthily assert and uphold categories and ontological gaps that are more imagined than real. Just as it is difficult to dismantle the master’s house using the master’s tools (but not at all impossible, despite pithy verbal assertions to the contrary), it is a difficult undertaking to argue against dualism using a language that is deeply dualist in construction. Yet “I” try.

The Choice

Let’s dig a bit deeper into the three serious choices enumerated above, in the order they appear.

Dualism

We can’t rule out anything by thinking about it, including the possibility that mind and matter are indeed fundamentally distinct. Maybe DayKart was correct in this core belief. This viewpoint is certainly pervasive in modern culture (roughly 80%), even among those who shun the term.

Yet, dualism still bugs enough people in its clumsy embrace of two separate—or even inseparably parallel (panpsychist)—phenomena: how would ontologically distinct “substances” interact? The ground on which dualism stands is also constantly eroded by experiments (often, unfortunately, involving animal abuse; DayKart would be proud) that relentlessly implicate matter—atoms, molecules, proteins, and neurons—in the phenomenon of mindful activity.

While not in itself a valid rationale for combating dualism (an example of working backwards from a position of affinity), the attitude does have a devastating impact on the living world, as stressed before. To highlight the departure of dualism from more ecologically-sound habits, ask: what would an animist (or unimist) do?

Abandoning dualism leads toward monism: only one “substance” is real. These come in two flavors: idealism and materialism.

Idealism

The notion that consciousness (mind) is the one true “substance” of reality, and that matter is generated notionally in minds is called idealism.

It is certainly understandable how this belief could emerge, since for each of us as “individuals,” the entire awareness of our experience filters through what we call the mind (involving brain/body/surroundings). The mind is “our” conscious window (mapped awareness) to the world, and can be (mis)taken to be the world—full of entertaining stuff projected onto it, much like a TV screen taken to be the reality it reconstructs in visual form—as my cats believed when images of birds or chipmunks painted the screen and their claws tried to snag tasty treats. Like any of these brain-tricks, no one can prove it wrong, any more than we can prove we’re not in an elaborate computer simulation or that invisible microscopic purple platypuses control the universe.

While I can respect the embrace of idealism as a laudable escape from dualism, I can’t personally resonate with a solipsistic worldview lacking actual matter. It seems like the most supremacist possible stance: only I matter; I define the universe; I think, therefore I am (DayKart’s mind-substance speaking for itself). It’s hard to get past the self-centered nature of idealism, and it also leaves me wondering how the universe (which, admittedly, my hangup says is real and not mentally-generated) got on before even stars formed—let alone “mindful” beasts. I can’t say for sure whether animists would embrace idealism, but something feels very off about it. Where is the humility or de-centering? Where is the dirt and the rock and the river as integral members of the community? Where is shared reality, if minds create their own private universes? All that said, I recognize that affinity—or lack thereof—is working backwards, and no basis in itself for determining how the universe works.

Back to more substantive beefs, I get hung up on this related aspect: if minds are all unique and private and un-sharable—each generating an illusory material “reality”—why do all physics experiments around the world agree on the same set of particles and interactions? Where did the idealistic freedom go to assert material realities as unique as the minds generating them? I mean, if we get to create “blue” or pain or any sensation in our own unique, private way, why the moratorium on doing so for matter? “What’s it like” to live in a universe constructed out of any constituents and rules that the mind wishes to generate? Can I have ice cream for dinner from now on? Can we also dictate material consequences? Are we each entitled to our own personal periodic table? Is any answer on a chemistry exam therefore absolutely correct? What fun!

Some might be tempted to attribute this convergence of observable physics to cultural forces, but I would suggest that such views operate in stark ignorance of physics, of how experiments work, and of how scientists strive to break paradigms and become famous. Also, an extraterrestrial culture pursuing physics would have no choice but to arrive at exact analogs to the electromagnetic field equations, quantum mechanics, and general relativity—without Maxwell, Heisenberg, or Einstein or any of our cultural history—because the same universe dictates the same reality to all of us. Again, I betray my strong sense that the universe (in its one way) exists apart from myself. Maybe I need ego-boosting pills?

Idealism strikes me as being captive to one’s own umwelt, taking literally the projection of a complex reality onto a manifestly stripped-down mental model. It’s putting the map over the territory. I have a question: why even bother conjuring bodies and brains, why do we all do it, and why does material complexity (i.e., brain architecture) accompany mental complexity across the Community of Life? I’m also stumped by this: do idealists ever stub a toe in the dark by mis-modeling where the bed is? Why would their mind conjure fake matter in such an inconvenient place, and how could it surprise itself so unpleasantly?

To a materialist (or dualist, for that matter), the real universe is not Minecraft. In fact, I wonder to what extent indoor kids raised on video game consoles and virtual realities and dinosaur-shaped chicken nuggets are inadvertently trained to develop idealist leanings (quite opposite an animist kid’s experience).

Again in the dubious manner of working backwards from a position of affinity, I also worry that treating mind as the basis for reality leads to a hierarchy of minds: both within humans and in the broader Community of Life. Indeed, those attracted to idealism tend to have sharp minds that they likely admire in themselves. How is idealism (or dualism) not at its base shameless self-flattery? Even if acknowledging minds in all living beings, the idealist likely does not assign comparable value to newts and humans (plants and microbes are right out!), or perhaps to all humans and themselves. I’ve got a bad feeling about where this could go…or has gone, actually (dualists are also guilty of mind-worship).

Materialist Monism

Materialism (sometimes physicalism) says that only matter is real—and all its interactions are described by physics. It may seem little wonder that I—as a physicist—find myself in this camp. Yet having worked for decades among physicists, I would venture that a healthy fraction (a majority?) are the usual products of our culture and are actually dualists like most people, even if self-identifying as materialists when asked. Yes, they’re committed to exploration in the domain of matter, but can still admire minds and human greatness (and their own, often enough). I was like most of my ilk: if you had asked me a few years ago what my metaphysical position was, I’d have no answer and link the word “metaphysics” to “supernatural” or “paranormal” and want nothing to do with it. I also harbored unexamined dualist assumptions when it came to matters like mind, determinism, and free will. I suspect many or most scientists do as well: philosophy seldom comes up, and is not explicitly a part of scientific training. Thus, despite reasonable assumptions, it is not at all a given that physicists will be materialist monists. That said, getting there is an easier step than for most, having gained a thorough grounding in material interactions.

If both dualism and idealism are evidentially problematic, materialism becomes my default home—even though some aspects of it are unsettling to me (yet, my affinities are irrelevant to the universe: that’s not the basis of my landing here). Settling on materialism isn’t to say that all of physics is locked down, or that new discoveries aren’t possible. But, importantly, neither need it be interpreted as a claim that we can ever draw the full map (although plenty of self-identified materialists have complete faith that we will, possibly pointing to hidden dualist/supremacist foundations). Relinquishing the demand for full understanding, the position becomes that no elements beyond matter and its governing physics need be involved, and the universe has—impressively—found a way to generate all that we experience using this basic set of matter and interactions.

I can’t stress the interaction aspect enough, though. Rather than imagining (in a characteristically-impoverished mental model) material constructions as inert lumps stuck together, think of every atom and molecule as waving advertisements/enticements to all passers-by, without rest. And arrangement matters a lot, so that molecules can be highly selective in their preferred clientele and how they behave in various contexts. The richness available is far beyond our imaginative capacity. Mental models just can’t do it justice. I’ll say more about the dominance of interaction in a few paragraphs, but it is worth heading off objections on the “inert” basis. The microscopic world of “inert” matter is anything but “dead.” It’s buzzing with unstoppable frenetic activity all the time. It’s incessantly animated—by physics!

In the (strictly) materialist view, all that we experience is built on a foundation of matter and its interactions, including our sensation of consciousness. Don’t ask me to explain exactly how. Nobody can (yet?; ever?). The complexity is overwhelming and beyond our ability to track. But this is very important: not fitting into our brains and mental models is no basis for rejection. Seriously. Why should we expect brains that evolved to supply adaptive advantages to a social mammal to be capable of comprehending the full story from first principles (physics) all the way to something as multi-layered and sophisticated and long-in-forming as consciousness—when we’re incapable of designing a single novel protein let alone a brainless amoeba? We’re lucky to be able to perceive the merest hints! Remember that a three-body problem or helium atom defies exact treatment. Rejecting materialism on the basis of too-complex-for-our-brains is itself a bit of an idealist-supremacist protest: “if it doesn’t fit in my brain, it can’t be real.” Oh, yeah? We’re back to my stubbed-toe-in-the-dark come-uppence.

Accepting that we are “as dirt” is about the least supremacist embrace of humility that we might deign to don, and hews closer to animism.

Oneness

Let’s briefly check back in on the idea of oneness presented in the second piece in this series, and how materialism meshes. Right off the bat, the word “oneness” implies monism more so than dualism. It’s easier to be one with the universe if not splitting yourself between mind and body, awkwardly placing one foot in each camp.

The idea that we are stardust, and made of the same stuff that all the plants, animals, and Earth itself contain is a very unifying truth. Everybody plays by the same rules. We also need all those entities/interactions to live ourselves (sun, moon, electromagnetism, gravity, rock, water, minerals, microbes, plants, fungi, animals). If we’re all based on material and its interactions, we’re all related. The line between animate and inanimate blurs, but in a way that doesn’t change one bit the fullness of what we are: only erasing an artificial demarcation in our faulty mental models. Dualism works in opposition to the oneness of animism and its embrace of rivers, rocks, mountains, weather, etc. as integral, inseparable constituents (people) in the all-inclusive Community of Life.

Thus, again, materialism finds surprising compatibility with animistic beliefs.

What’s the Matter?

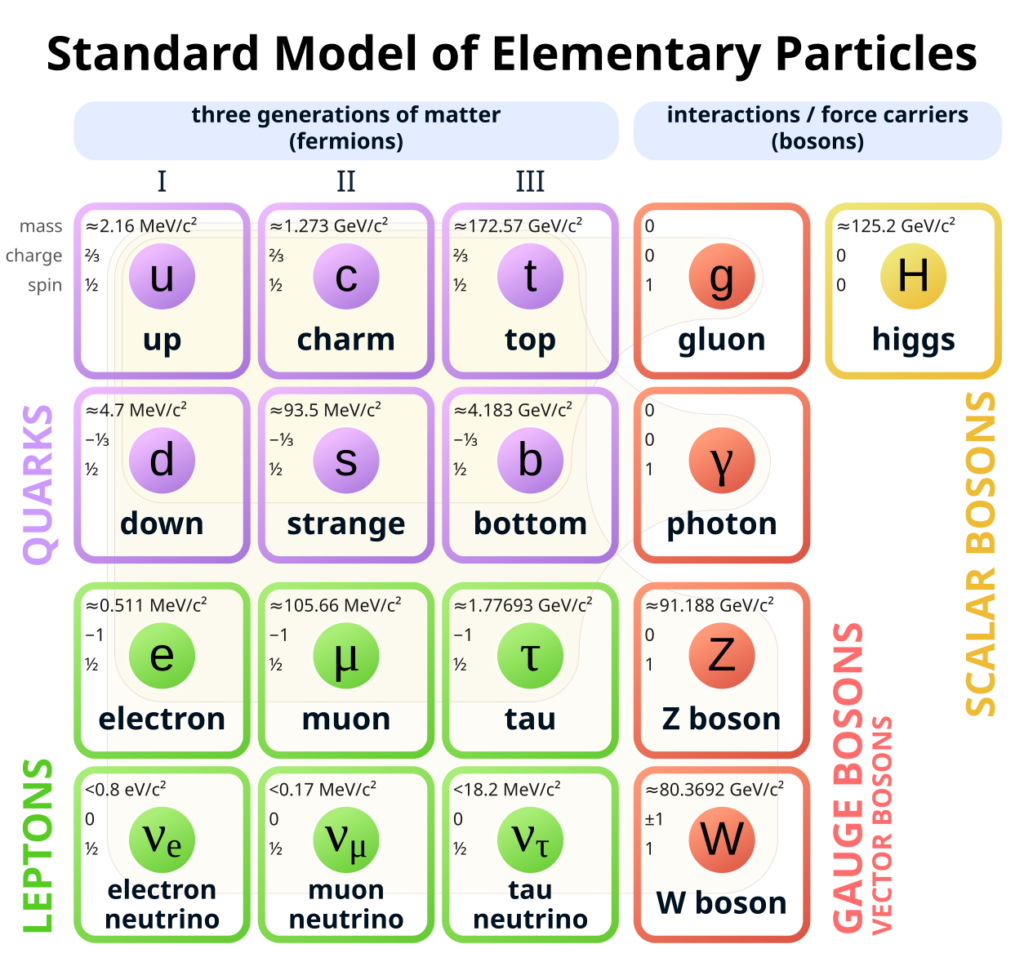

Everywhere we look, we find atoms. Probing deeper (in accelerators), we find their constituents: three generations of quark pairs, three generations of leptons, and “force carrier” particles like photons, gluons, etc. (plus their anti-matter doppelgängers). Normal matter only involves the first generation of quarks (up and down, combining to make protons and neutrons) and the first generation of leptons (electron). It takes only a single page to cover all the fundamental particles and their properties (mass, charge, spin, etc.).

The fundamental interactions—gravity, electromagnetism, weak and strong nuclear forces—are easy enough to list and describe, which could be packaged into a thin pamphlet. But as a matter of critical importance, interactions far outnumber particles.

Interaction-Dominated

Let’s just take the Earth as an example, which has about 1.4×1050 atoms, or about 3.6×1051 nucleons (mass-bearing protons and neutrons). However feebly, every particle feels every other (e.g., gravity, but also via electromagnetism—even neutrons are composed of charged quarks). Given N particles, there are N×(N−1)/2 unique interaction pairs, so that Earth alone tallies 6.5×10102 interactions just between nucleons (far more if counting quarks and gluons and electrons, etc.). But there’s much more to the universe than Earth, and the basic idea is: however many particles you’ve got, square that number to get an estimate of interactions. It’s like placing a large bet and getting raised by an insane amount: you put in $20,000 and get raised $200,000,000. Interactions always win—by an outrageous margin!

The thickness of physics books and journals and all the rest of a library’s collection attests to the complexity emerging from the “simple” interactions. It’s a lot. Then all of chemistry, all of biology, and all of ecology stem from here. Guess what: it doesn’t stop there. Materialism has it that everything in the universe (thus every subject at a university) is an expression of material interactions, driven to hopeless degrees of multi-layered complexity that quickly defies a first-principles materialist approach, so that university departments are justified in not even attempting it (less justifiably sometimes denying the foundation). But just try to stop complexity from emerging! Our ability to track is not a criterion the universe considers in configuring itself. Proteins don’t need our permission or understanding to fold into functionally-selected forms.

The Rule of Atoms/Interactions

Repeating a line from above: everywhere we look, we find atoms. Our tissues, brains, and DNA are made of the stuff. Cognitive complexity tracks organism complexity. As mentioned before, it would be odd if matter is a mental construct: given that we can’t even be sure that we all see blue the same way, we somehow get atoms and quarks and the interactions the same? Indeed, we find complete repeatable agreement to very high precision. No single aspect of life is shown to operate without dependence on matter (atoms). In the materialist view, every thought you have is a material expression requiring neurons, electrical and chemical signals, and metabolic activity (and rocks and the sun, for that matter). No one has yet demonstrated a thought free of substantial (complete) material encumbrance… and don’t hold your breath waiting for it to happen.

As another significant clue, even small amounts of chemicals (interacting matter!) can alter, disrupt, suspend, or even terminate consciousness. Drugs and anesthesia come to mind. Personalities become almost unrecognizable under the influence of many narcotics. Atoms therefore exert tremendous power over the experience we call “mind,” which is an easy pitch when mind is an emergent product of material interactions. Neither dualist nor idealist foundations can account for these ubiquitous phenomena as effortlessly.

Best Option?

Despite the fact that matter and its interactions are implicated everywhere we look, we’ve only barely scratched the surface, and can’t reasonably expect to paint the full picture. It’s like plumbing the depths from Antarctica to Hawaii: superficially very different places. Even though the connecting “land” under the ocean is invisible and might be imagined to be imaginary, everywhere we drop a probe, we hit bottom, and find rock. It is reasonable to assume after many thousands of such probes (finding atoms involved in every life process we study) that we’ll find the same story everywhere, even if not ever able to fully map the route and conclusively eliminate any number of speculative gaps. Never finding a single gap is surely also relevant, yet some will no-doubt cling to the increasingly-remote possibility that one day…

For all these reasons, the resolution that makes the most sense to me is to accept materialism as the only metaphysical foundation we need to permit the marvelous richness that we experience. (The word “accept” is loaded with a false sense of authority, as if I have any say.) The other non-dualist option is idealism. Does mind make matter, or matter make mind? What partial evidence we possess appears to favor the latter, quite overwhelmingly. Materialism expresses a humbleness where idealism requires self-centeredness—shared by dualists—which I think carries important consequences. I can only argue that materialism appears to make the most sense and seems to describe the universe as we find it without appealing to “extra” layers. No one can argue that they have the truth of the matter, but setting preferences and affinities aside, no one can credibly claim that materialism is patently insufficient for the job. Complexity has a lot of juice.

Where Next?

For many, the notion that our experiences have a strictly material origin is deflating and demeaning. It needn’t be, under a different (non-dualist) mental model and an alternate source of meaning. But to better understand the difficulties, we’ll take a look at the nature of key objections to materialism next time.

Views: 2816

It strikes me that animists are dualists or possibly idealists, more than they are materialists?

I’m not convinced that being dualistic has the entirely negative consequences that you are attributing to it. It seems, to me, more likely that it is trying to crow bar our worldview into a purely materialist monism that has given rise to our alienation from ourselves and the world…

I'm not in a good place (or time) to judge what animists were or were not (if even monolithic, which I would doubt). Some extant groups have no afterlife belief: your body becomes meat and nutrients and tools and whatever. Imbuing personhood onto rocks and mountains can be interpreted either way. In any case, lacking the knowledge we've gained, it would not be reasonable to expect the same sort of physics-informed materialist monism among animists. The key is that they tended to view all matter/life as a single phenomenon rather than a split.

But to be clear, the trajectory of modernity (for millennia) has been thoroughly and predominantly dualist, so I would sooner chalk up the ills to this pervasive worldview than to materialist monism (surprisingly rare without dualist taint). Alienation is precisely a dualist result: separating ourselves/minds from a single bulk reality. The ills come from instrumentalizing the "dead" matter in service of "live" mind. We simply have not run the experiment of an actual materialist-monism culture, but it has potential to overcome the supremacist behaviors of dualist cultures (ours).

“As I have mentioned before, the more we insist on monotheism and shut out the other gods, the more they clamour at the back door – and the more rigid and puritanical we must become in order to keep them at bay. Our religion narrows to ideology. We cling to a single, literal creed and condemn any imaginative variant as deviant or heretical. We become fundamentalists, whether Christian or Muslims, Marxists or fascists, rationalists or materialists.”

Patrick Harpur

Beautifully put, Tom (in my opinion).

I have found myself wondering lately if, in some sense at least, the phenomena of life and consciousness essentially amount to the existence of a “self” that must believe in BOTH a dualist framing of reality (and free will) and a materialist monist framing of reality, the latter of which must be ultimately deferred to in the end. Another way to put it might be that the belief in these two realities is embodied in an organism (I kind of think that consciousness/self/life are one and the same in some sense).

A dualist framing is necessary for the self to *want* to sustain itself as a “separate” self (“will” is required to sustain a state of “negentropy” in the face of the second law), and a materialist framing is necessary for the self to not lose sight of the obvious fact that food, maintaining/moving to a suitable environment, avoiding predators, etc. is necessary for it to exist at all.

The dualist framing represents a reframing of reality to accommodate the notion of the separate self. The separate self is not an absolute truth, but there is a sense in which the ”separate self” is “real” and makes sense (a sense that only makes sense to the self?!).

It’s just us modern humans that seem to have *talked ourselves* into believing more, or exclusively, in the dualist framing, and jettisoning our belief in the monist framing… and thence on to ideas like the mind living on in heaven/hell after physical death (some of us really do believe we can exist without eating!). We believe in the completely separate “I” way too much, and have forgotten that there is a view to be had of us from the outside: we are not just the observer, we are simultaneously an observer and the observed.

… I just realised I am essentially saying what Ian McGilchrist says in “The Master and His Emissary” 🤦 I always was very slow on the uptake…

Maybe the origin of both life and consciousness really did start with the proto-cell, which created an “inside” and an “outside”? Maybe this is also the ultimate source of the dualist framing of things? The inside of the proto-cell would eventually become the site of the self/consciousness/negentropy, to be maintained as “separate” to the “outside” environment. And then on from conscious single cells to…

It is worth noting/stressing that a feature of cells is their degree of interaction with each other. Cooperativity seems to be a major theme, such that Life seems to be one big interconnected web. Cells want to sustain themselves as individuals but also recognise/“recognise” (I honestly don’t know which of these is closest to the truth now) that they must serve their role as a part of a “greater” whole: the phenomenon of Life. Ultimately, this cooperativity seems to/must have its origins in the laws of physics themselves (or another way to say it is that the laws of physics capture this tendency towards cooperativity). Perhaps grossly anthropomorphising here, but even particles themselves just seem to want/“want” to cooperatively build things together! Ok, yes, this last bit is probably really stretching it too far!

I guess you could even go so far as to say that Life itself (considered as a single entity) also regards itself as separate to “inanimate” matter, but also understands that it isn’t at the end of the day. Again, forgive the anthropomorphising, though I increasingly find myself wondering if us “anthropomorphising” a little more may actually help us to let go of our human supremacist tendencies, and might actually end up bringing us closer to an understanding of what life actually is. Maybe what we call “anthropomorphising” isn’t really anthropomorphising at all, but simply us acknowledging that all other life has consciousness…

Another way to square the “unresolvable” beliefs of dualism and materiaism that I suggest an organism must carry in order to posses the will and capacity to exist as a “self” is for an organism to embody a singular belief in panpsychism. The two beliefs collapse into one in this formulation. It may not be the literal truth, but it makes the unresolvable tension a harmony *from the perspective of the self*. Monist materiaism also collapses the two beliefs into one (consciousness is an illusion) , but perhaps this is only achievable by the “zen masters” of materialism. Which is the truth? Who knows. As long as the worldview works to stop us doing what we are doing, all good with me. Dualism may not have been the root cause for modernity (it probably developed and strengthened as modernity progressed), but ditching it is the only way out of modernity I think.

Quick retort to the idealist conjecture that everything is mind or that it’s all a giant computer simulation: if reality is simply a projection of mind, the apparent repeatability of phenomena is because, like Abbott’s inhabitant of Pointland, there are no others. All is oneself (radical monism) and presumed others are either figments or multiple personalities. Fits with DayKart’s solipsism. The four dimensions humans experience are conventionally understood as three material dimensions and one of time. The possibility of further dimensions lying outside human perception prompts paranoia about inscrutable interdimensional aliens (or gods) among us. We would scarcely know.

Regarding the different “substances” of the dualist ideology, let me propose something I have never before read, thought, or written. What if time is in fact a material dimension? More specifically, is time simply material in motion? If matter has three (or four) phases, then matter in its Newtonian sense, while in a flow state rather than being static or fixed, captures some portion of the interactions you write about and makes material the time dimension. So a nominally still pond or lake in motion becomes a river — still material but far more dynamic. Properties and interactions that emerge from the flow state might also account for consciousness and yoke everything to a material reality.

I’m surely grasping here but wonder if such a concept doesn't at least address the both/neither answer to the question “Is is a particle or a wave?"

Good point about idealism (as it was defined here). If my mind has created everything else, I can't say anything about other people's minds because the only other people in my mind are the one's my mind created. I probably can't say anything about even ME because there is nothing to compare against other than what was created by my mind (which may be the only one!). No wonder physics experiments agree!

But then my mind also created, for example, climate change deniers, and climate change itself. Why would it do that? Good argument against idealism – it's boring.

Idealism isn’t stating that external reality is being produced by or in your mind…that’s solipsism…rather that the substrate of reality is mind like…the universe’s mind, universal consciousness or the mind of god or whatever…

Matter is possibly

"Words and their grammar are all crude and clunky representations—not the reality they attempt to capture."

Yet here you are, attempting to capture reality… with words.

"We can’t rule out anything by thinking about it"

Well, I can rule out '2+2=5' (etc etc).

"justifying the savaging of mother Earth as a collection of commodified resources" is what *modernity* does, and the prevailing global 'culture' is now an empty, consumerist, science-worshipping, atheistic one.

(That's not to say dualism isn't false, just that leveraging modernity as an argument against it is disingenuous.)

The material world of atoms, molecules etc. is real – but where does matter itself come from? If no one knows (and they don't, really), it's of no consequence anyway, is it? Except to those who *need it* to be fundamental (maybe it is).

Another excellent post, Tom. Let me add some points from cybernetics.

First, how about the distinction between 1st and 2nd Order Cybernetics? The one has the observer viewed as separate from the observed, only recording input/output protocols to make inferences about black boxes. The other argues that no observer can be separate from the observed, the closer the watch the more is the coupling effect on the outcome. A bit that quantum science took a step further: once two systems have closely interacted they can never be fully separate again. Meanwhile, a quantum state observed directly implicates the observer. If not as the director of events, certainly the co-producer of its reality. Our individual mind through what we call free will can create a deterministic reality from the many simultaneous and indeterminate local states in quantum superposition through the deliberate act of measurement. But even that reality is a common reality. If a measured spin has one chirality, it will not have another for a different observer. Which, to my mind, must strengthen the materialist monist view.

It is a wonder why leading physicists, quantum scientists notwithstanding, can also be closet dualists. I chalk it up to an undemanding philosophical environment or just lazy philosophy. A situation I hope to change with the spread of the diagrammatic quantum language by Bob Coecke et al across more fields of science. Still, there is a subjective point of note: leading is also a social construct; leaders must subscribe to some kind of group think in order to lead. Though it can be their own making, what is bound to haunt it is that Life of Brian situation: "Yes, we are all individuals!" – proclaimed in monotonic unison. And the more complex modern science grows, it tends the less value neutral to become. Thus, I suspect that dualist or not, witting or unwitting, the bulk of practicing scientists will cling even more strongly to a matching ontology, phenomenology and epistemology. Come retirement though, they may see them in another light.

I cannot but heartily recommend even to the mildly scientifically inclined the "Introduction to Cybernetics" by the inimitable Ross Ashby. Step by step, he laid out beautifully in 1961 how goal seeking proceeds from variety and its inevitable laws leading us to observe things as beings having a will and mind/"mind" of their own. He also laid out how having memory in any system for one observer is simply a lack of more complete record of its inputs for another. It is full of eye-opening "Aha!" moments guaranteed to grow on you. Simply put, we recognize a system having a will or mind of its own because/(provided that) it persists. Beyond a certain amount of complexity and given ample time, such persistence is unavoidable. Which breeds more variety, hence more persistent interactions he calls couplings. Whether we see this as a property of the living or not is only a matter of scope; the richness of a system's input variables necessary to maintain its persistence basin regulator. Interestingly, the more complex the system and hence the more inscrutable it is to an observer, the more beneficial can be for it if said regulator's inputs from its environment are supplemented by random inputs from another wholly uncorrelated system.

A charged dust cloud arranging itself in a persistent spiral can pinch a copy of itself from another charged dust cloud not unlike an RNA string can pinch a copy of itself from the unruly matter swirling and buzzing around it in the surrounding cytoplasm. Which one has more of a mind (and will) of their own: the inert dust cloud or the lifelike string? Indeed, as Tom said it so well, it is only a matter of scope. Or matter squared: matter of substance times matter of scope.

Even dusty plasma, under experimental conditions of certain field arrangement and clumping size, can exhibit what could be described as seemingly having a mind of its own in a remarkably life-like behavior.

You know Descartes used to call himself Cartesius (latinized names seemed to be all the rage back then), and therefore, "Cartesian" does make a lot of sense, right?