Now we turn to one of the more perplexing aspects of materialism: one that prevents many from abandoning dualist beliefs. How can sentient living beings possibly arise from matter alone? Dualism asserts a sharp ontological divide between animate and inanimate (mind and matter as a parallel aspect), categorically prohibiting animate beings from being wholly composed of inanimate matter. The last post addressed the flaw in characterizing matter as being “inert” in the first place.

But even once past this barrier, our inability to connect all the dots from atoms to conscious experience (which no one has managed to do, and likely never will), strongly tempts us to declare—assuming phantasmic authority—that no such route even could exist, or that failure to map it means it may as well be declared non-existent (a reaction worthy of the Ravenous Bugblatter Beast). Where’s the adventure in that?

As an aside, allusion to “phantasmic authority” above may elicit the reflexive charge that advocating materialist monism is an equivalent assertion devoid of authority. Not so fast. Materialist monism amounts to being satisfied that matter/interactions can plausibly form the entire basis of reality even if we don’t understand how. It is in claiming materialism to be insufficient—without evidence—that meat-brains seize more authority than they are due. Materialist monism cedes authority to the universe as we find it, rather than presuming to fabricate comforting alternatives.

Anyway, lacking a complete map, how does materialism deal with our experience as sentient beings, or other sentient life? We find a significant clue in the etymology of sentient. The root word is “sense.”

Sensing

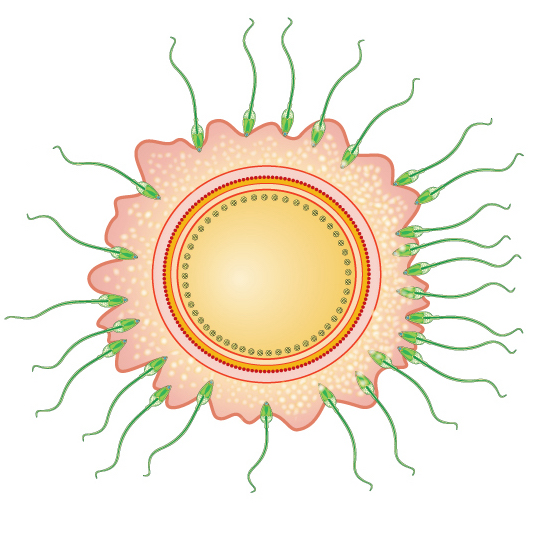

Microbes sense and react to the conditions they encounter, as do spores, sperm cells, seeds, plants, fungi, and animals. Many technological devices we manufacture—as pathetic as they are compared to living beings—have no trouble accomplishing these feats either, in their clumsy ways. By comparison, when it comes to building sensors, Life frequently far surpasses technological efforts in terms of elegance, complexity, efficiency, and compactness. Clunkiness aside, sensing-and-reacting, then, is not the hard part.

All Life—or all matter for that matter—is empowered to act and react in this world in ways that necessarily effect change in the world beyond themselves via copious channels of interaction. But what is the nature of this empowerment? Well, the actual process might involve mobility or material exchange or other mechanisms, and these mechanisms can (sometimes) be traced to fundamentals given enough patience. But how is sensing connected to action? In microbes it might be that sensed conditions trigger generation of certain proteins whose presence compels a particular action, like motion. Already beyond Rube-Goldberg complexity in microbes, the chain of events in more sophisticated organisms heaps on even more interdependent layers. The situation becomes virtually impossible to trace, yet continues to be based on incremental material interaction at every stage—one building off the last like a series of levers might do (a woefully inadequate metaphor, to be clear).

But how does the organism know what to do, so that it executes good/adaptive decisions? That’s the magic of evolution: it keeps organisms that are configured to respond appropriately, and terminates those who aren’t. So, even a random choice will be “good” in some circumstances, and that choice—together with the mechanisms leading to it—has the opportunity to get locked in. Life, in a sense, is a scheme for locking in adaptively beneficial interactions in contextually relevant scenarios. This is the power of feedback in the presence of self-replication. Those organisms that “self-wire” to make advantageous decisions pass the blueprints for that wiring along—whatever the complexity. It’s a fantastically clever utilization of available physics (and chemistry, etc.) to accomplish something remarkable given the tools at hand and unimaginable patience over deep time paired with random trial. And the great thing is: the mechanism has no choice but to emerge of its own accord once self-replication is in practice. Nothing can stop it!

Now, I consider (assume) microbes to be sentient problem-solvers (able to judge good and bad—valenced—scenarios and respond accordingly), so I’m satisfied with sentience already at the microbial stage, even if the details far exceed my/our capacity to fully track. But if we want to crawl our way toward beetles or fish or parrots or dogs, we would need to pile on far more complexity than our brains can handle, never in the process being forced to resort to interactions outside of physics. Not having the whole picture ourselves does not at all mean the picture can’t be painted by the universe itself over billions of years of trial and error in feedback. To declare it impossible seems a hasty, arrogant, and evidence-free assertion that says far more about our own cognitive limitations and emotional needs than it does about how the universe actually works.

Our imaginations are no match to the deep wisdom emerging out of the eons. Mental models formed in brains have the luxury of skipping over vast tracts of complexity and interaction, but actual Life has no choice but to operate in the full context of everything at once, all the time. More power to it! Indeed, Life’s power will outlast our own.

What it’s Like?

Now let’s try returning to the perennial question that confounds contemplation of consciousness. What is it like to be conscious? The experience is private and presumably unique to an individual. Every experience feels like something. The key question is whether anything in materialist monism would somehow prevent distinct sensations (and on what basis)?

Pause for a second to ask what it would mean if sensory experiences did not have a unique feeling. Would they even register? Could they even be called a sense? How would the organism even know he or she (or it, or ki) is having the experience if they couldn’t feel it in some manner and differentiate it from other feelings?

Let’s take a moment to acknowledge that the presence of certain chemicals (atomic arrangements) in the brain influence how we feel. Dopamine, adrenaline, oxytocin, and serotonin are among the cocktails released in our brains/bodies to alter how we feel. Likewise, narcotics produce their own feelings, and anesthesia feels like absolutely nothing (a non-experience). Matter—even in tiny amounts—changes what it’s like to experience life.

Meanwhile, hot water on the hand feels different from seeing the color blue. If it didn’t, how would we (or any organism) know which we’re experiencing? And how is an organism to survive if unable to differentiate and react differently to dissimilar stimuli? If an experience didn’t feel like something, could we even claim to have sensed it? By “we,” I mean all Life, including microbes or even a completely inactive spore waiting to feel (sense/differentiate) the right conditions to “hatch” after millions of years of complete dormancy.

For human anatomy, conscious awareness involves representation in the brain (presumably largely transpiring in the prefrontal cortex, which is explicitly wired to access activities across the brain). What would be the benefit of experiencing something and keeping the brain in the dark? How could one act on or learn from the experience if not privy to the uniqueness of how it feels? It seems highly relevant, and would be very strange for evolution to have gone out of its way to exclude any form of awareness of the sensation, when said awareness carries obvious adaptive advantage.

Feeling involves sensing (for emotions, too, as complex multi-layered feelings). Discriminatory sensing means feeling/experiencing differently (able to tell sensations apart). How would existence be if every sensation or experience produced either no feeling or the exact same feeling?

A group of neurons that fire when presented with the color blue surely won’t be indistinguishable from the neurons that fire at the experience of being licked by a cat’s tongue. The hardware produces different firing patterns in space and time, which are thus detectable as being different, each producing a unique signature (feeling). Even when imagining the color blue (e.g., with eyes closed, bypassing ocular input), some of the same neurons are activated in the chain of identification as when visually exposed to the same color—not surprisingly.

The hardware is really important, here. What does it feel like to be in an electric field of 10 volts per meter vs. 100 V/m? Nothing, to humans. We don’t have sensors for that. What does it feel like to sense a 3D world via echolocation? No idea: we are not so-equipped. To answer Thomas Nagel’s question of “What’s it like to be a bat,” we could only know by being a bat, with 100% bat hardware and 0% human hardware. Modern dualist languages again become problematic, because “we” assumes some non-corporeal aspect that conceivably could inhabit some other material construction. So the contemplation fails to make any sense in a materialist framing. There is no “we” apart from our specific material construction, so that talk of “us” inhabiting a bat is just Freaky Friday gibberish.

But it’s pretty certain that to a bat it’s like something to be a bat, otherwise what’s all that hardware even doing if not generating distinguishable states or signals on which to act accordingly? For those of us utilizing brains, the complexity of the brain speaks volumes, so that what it’s like depends on what the brain can do in partnership with the body. A cricket won’t be able to perceive the world as humans do (and vice versa). In our case, a prefrontal cortex explicitly links to many other regions of the brain to monitor activity and “direct traffic” for potentially competing urges. It stands to reason that our self-aware window is largely situated in this part of the brain that is explicitly (in hardware/”wiring”) tasked with metacognition: modeling what (parts of) our own brain is doing.

To avoid the charge of neuro-supremacy, the experience of any organism that can sense and react (thus, all of them) must feel like something. Even without brains, chemicals and proteins alter the state of plants and microbial organisms in ways that are obviously differentiable, and thus “feel” different, even if we can’t imagine how indeed it feels different. Behaviors suggest that something is discernibly different. An amoeba in the presence of food or a toxin will manifest (presumably) chemical or protein states unique to those situations, producing different modalities and sensory feelings and thus reactions.

Machine Objection

Having fleshed out more on how sentience can conceivably emerge from sensory mechanisms, we can return to the “machine” question initiated in the last post. For many, the suggestion that our experiences are “nothing more” than mechanics is deeply distasteful: we are clearly not mere machines.

There’s so much to say here, it’s hard to know how to order it.

- The term “machine” is loaded and generally construed narrowly via comparisons to our pathetic technological kludges.

- One could elect to expand the term “machine” to mean any arrangement of matter that performs some function. Stars are then machines, as are sticks and hurricanes and alligators. If humans are not fundamentally/strictly mechanical/material in origin, we’re back to dualism or idealism.

- Our inability to create machines even remotely as sophisticated as an amoeba or even a novel protein in no way sets a limit on what the universe can cook up over billions of years accessing matter and its interactions.

- The complexity of nature’s “machines” is through the roof: far too much for our brains to track. We’ll never build anything even close to the sophistication of living beings (at best, some will mimic a tiny slice of what Life does, by parlor-trick “cheats”).

- “It can’t be so” is harder to defend than the more honest “I don’t want it to be so” or “I can’t comprehend how it could be so.”

- The universe needn’t alter its foundations according to our tastes or distastes or limited cognitive capacities.

- Where does the objection come from, deep down? Is it fundamentally from a sense of superiority (better than a machine) or tenacious dualism?

- A general sense might be that having mechanistic origins somehow degrades us (from what imagined status, exactly?), the implications of which are worrisome.

Molecular Machines

Let’s take a moment to appreciate the fact that living beings form all sorts of micro-machines to carry out basic operations. Below is an example of a flagellum motor that is—for biology—uncharacteristically dumb and simple enough for our constrained cognition to recognize as resembling our own clumsy machine designs. Most biological machines are too sophisticated to remind us of our geometrically-idealized Lego inventions.

Although highly idealized for visual clarity (reality is far messier and fails to provide such clean views), the following 3-minute video offers astounding depictions of clever biological machines at work in living cells.

The next 3-minute video provides an overview of the mechanics involved in protein synthesis from DNA—again stylized to aid meat-brain comprehension.

The point is that incredibly intricate “machines” abound in biological contexts. If it all seems too outrageously sophisticated, that’s exactly right. But that’s because billions of years of trial and error under the relentless eye of selective feedback can far outperform our synaptic struggles to understand. All these myriad mechanisms contribute to sentience: the ability to sense and react to conditions in service of survival. It’s no small feat, and too insanely complex for us to have any expectation of fully internalizing in mental form. That’s our problem, not nature’s.

That Elusive Spark

I watched a recent video of brilliant polymath Roger Penrose musing on consciousness. It is apparent to many that artificial intelligence (AI) is not at all the same thing as our experience of understanding the world as sentient beings. Large-language-model AI is an impressive, brute force parlor trick that projects a simulacrum of “thinking” (in the limited way we often define thinking) by stringing together words (or pixels in the case of images) in ways that are similar to what humans are accustomed to encountering and producing.

Penrose suspects that some key is missing that makes our thinking non-computational, suggesting perhaps the collapse of the wave function as a phenomenon in physics that cannot be algorithmically represented in a computer. In other words, life has some “spark” that can’t possibly be captured in a computer.

I completely agree, but for wholly different reasons. Digital computers lack the nuance, rich sensory umwelt, architectural sophistication, and ecological pressure/shaping to remotely compete with surviving analog tangles of insane complexity. I would not expect the gulf between computers and humans—a legitimate and quite substantial gulf—to be bridged by a single tidy idea like wave function collapse. To be clear, by calling it “gulf,” I don’t mean an ontological gap that cannot even in principle be crossed, but a distancing that is nonetheless connected in ways we don’t directly see—much like distant and dissimilar islands separated by an unseen but no-less-substantial ocean floor made of rock. The universe indeed may have found a circuitous route to construct Life out of atoms over billions of years of effort. But suspecting that a single tidy idea can solve the mystery is where we often go wrong. We try to reduce the insanely complex phenomenology to a single trick—which our brains are more prepared and eager to accept and handle than incomprehensible complexity.

Yet, it doesn’t have to be one trick. Differences between computers as we build/program them and animal cognition abound. Living beings are intimately immersed in incredible sensory input, thus connected to an experiential world in ways that computers very much are not. Living beings are shaped by stringent requirements to “think” well enough (on average) to survive at a species level, in whatever complicated interactions they might expect to navigate—up to and including social and political “calculations.” We also rest heavily on a billion-plus-year heritage in shaping complex responses to complex stimuli. Living beings learn not by imitating training sets, but through repeated cycles of experience and consequence. The first 25 minutes or so of this video exposes a stark divergence in algorithmic vs. biological thinking styles. Guess which guy I trust more? The contrast is almost embarrassing. Sutton uses a squirrel in his example, but I might even argue that an amoeba is closer to human experience than is AI (after all, we share a third of an amoeba’s genes, and 0% of a computer’s).

So, it seems that the machine-aversion fallacy (and preference for a singular defining “spark”) is borne out of an incapacity or impatience to consider that a huge—but exquisitely-arranged—collection of mundane yet highly-interactive matter can contrive (through painstaking trial and error under selective feedback and constant sensory connection to an immense and rich world) to produce behaviors far beyond the ken of pathetically narrow, recent, and profoundly isolated digital computing machines.

In other words, accounting for the enormous gulf between living sentience and industrial machines need not be some ethereal “substance” or mind-blowing quantum phenomenon. The universe is quite practiced at piling up the mundane to make something spectacular. If a mundane—but exceedingly complex—explanation is possible (in principle, even if too woolly for primates to actually pull off), why not go with it? More to the point, what stands in the way of the universe from taking that readily-available path whether it suits our preferences or not.

Redefining Machine…

By dropping the unnecessary restriction that any use of the word “machine” refers only to a technological device of human design and fabrication, one might more broadly use the term to describe any arrangement of matter adhering to the rules of physics (i.e., “mechanistic”). Set aside for now our inability to fully comprehend the degree of complexity that might emerge. We needn’t demand full understanding to believe that an interactive material basis applies.

Moral implications need not ride in with the term: a name does not impact the actual entity to which it might attach… a rose by any other name and all that. Only our narrow mental models carry these associations, unnecessarily. Language constrains and twists apprehension.

For those who are still uncomfortable associating humans or other animals with the term “machine,” is it fundamentally because you believe animals (and plants and fungi and microbes) do not ultimately derive from matter interacting via physics?

It’s fine if that’s where you are: no one can lay claim to Truth. But just recognize that such a view is probably dualism—unless you believe matter to be a construct of mind (idealism, then). If you deem matter to be real, while believing in some immaterial aspect of Life that can’t be represented by matter in interaction (via standard physics, for instance, and not some undetectable added aspect like a conscious quantum as in panpsychism), then I’d be fully justified in calling it dualism: vanilla physics plus the special sauce (dual ingredients). For a materialist monist, the special sauce doesn’t enter from an immaterial domain, but is made from “normal” (material) ingredients just like everything else: no transcendent infusions.

Some dualists likely reject the dualism label in part because of where DayKart (my term of disrespect)—and plenty of others in modernity—have gone with this view. For a dualist who believes in a “higher” plane, to call animals “machines” is to denigrate them, implicitly removing any barriers to cruel treatment. Please see that this machine-averse reaction is itself an expression of dualism: that if the animals truly are “nothing more than” matter in complex interaction, then they are not special any more—like humans presumably still are. In the dualist framing, something “special” (immaterial) is required to prevent cruelty, since it is (in this framing) impossible to be cruel to a mere machine (“inanimate” collection of matter).

This needn’t be so. As a materialist monist, it is possible to greatly appreciate the “miracle” of Life as a purely mechanistic phenomenon, which makes it not one bit less amazing and worthy of respect. Ask the newts who live around me if I treat them with respect and adoration—taking pains to protect them from modernity’s ills. For me, in fact, the prospect of Life establishing its amazingness on a material foundation only enhances my level of awe. We could never replace anything so amazing by our own handiwork, therefore are not justified in its abuse or destruction. Life is beyond our crude capabilities to fully understand or “design,” and all the more amazing for figuring out how to be in this world utilizing the matter and interactions provided on the minimalist menu.

Panpsychism as Inclusive Dualism

To repeat, believing that we possess both “inanimate” matter (wrongly assigned “inert” status) and a spark of animate consciousness (mind, soul, whatever) that is not explainable by plain materialism is to be a dualist. I view panpsychism as a sort of closeted dualism in that it rejects (under dubious authority) the notion that matter and standard physics alone can get the job done, instead requiring a companion aspect of matter—eluding any physical measurement, note—that collectively builds consciousness out of infinitesimal contributions from fundamental particles. It respects physics to a point, indeed trying to mimic the ground-up construction and emergence of something fabulous—just not by means of the physics we measure and confirm, or by any coherent set of proposed rules (no falsifiable theory). They might fool others and themselves into believing it’s not a twist on dualism, but fundamentally it requires something parallel to materialism in order to accomplish Life and consciousness, wedging an ontological divorce between “mere” matter and “life-defining” consciousness. I count two aspects, there: “Yes, material/physics is real—but we can’t make out that it’s enough and want another undetected dimension of reality to account for what we can’t understand.”

To be clear, and as mentioned in the introduction, the “authority” situation is not symmetric, as materialist monists do not assert that matter/interaction is all there possibly can be—rather asking why it isn’t enough for us, if we lack any strong case for why it can’t do the job. Who are we to reject the provided menu and “order” something more? Authority, for materialist monists, issues from the universe as directly accessed, assuming matter is real (rather than imagined, as in idealism). Materialist monists do not presume that we know better: that the universe is incapable of producing all that we experience based on the constituents and interactions on full display.

The key for panpsychists and other dualists is the dissatisfaction of ignorance. They would rather conjure/invent unbidden schemes lacking any evidence than accept limitations in our ability to track complexity using proven matter and interaction. Wanting more than materialism places affinity over economy, and comes across as an impatient grasp for a tidy explanation that satisfies the left hemisphere’s hunger for mental-model certainty. All that complexity is such an untidy headache!

Now, modern brands of dualism like panpsychism might be far more inclusive than DayKart was—extending membership to chimps, dogs, pigs, rats, birds, frogs, snakes, fish, worms, fleas, plants, fungi, tardigrades, amoebas, and bacteria, for instance. Well done, there. If the result is to curtail cruelty to life and end modernity’s human-supremacist reign, I can’t complain too loudly. Indeed, such groundings might offer a viable path for people so inclined to drop modernity, human supremacism, and any sense of separateness. Except minds are still special…

My residual concern is that such a view is still fundamentally supremacist: erecting artificial barriers to form “the club.” The “spark” that separates us from mere matter is some transcendent quality that presumably comes with privileges. By placing so much value on consciousness that it must require a special “substance” to instantiate, dualist views also tend to preserve a hierarchy of degree of this obviously precious phenomenon called consciousness that happens to place humans at the top of the (imagined) scale. This feels like the opposite of humility, and has a difficult time squaring with animistic reverence for “inanimate” arrangements of mindless matter like rocks and rivers and mountains. All the same, it may be one of several useful bridges to get us toward a better place.

In the next installment, I’ll address the “reductionist” charge often leveled against materialism.

Views: 2002

Great work, Tom!

My inset: although the first video is quite simplified, sometimes sped up, sometimes slowed down, and the cell looks empty (in fact, the contents are more like soup, in which a spoon would not float, but "stand"), most of the macromolecules and their behavior are modeled quite accurately, and for some processes there are already real videos (!).

Regarding life (and other material manifestations, in fact all), there are rare events that are probably impossible spontaneously, in reality, but which have successfully occurred, thanks to one of the most complex manifestations of matter (human activity). So, yes, everything that is not forbidden by physics is possible, and it is an amazingly rich sandbox in terms of the number and levels of interactions.

Thanks!

Your series of posts is fantastic. Thank you.

ICYMI:

Novelist George Saunders, in an interview this week: "You know those three things that you’ve always thought of? They’re not true. You’re not permanent, you’re not the most important thing and you’re not separate. So I think about it a lot, but I find it a joyful thing, because it’s just a reality check."

It's a start.

https://archive.is/gRPuk

I love this. I will keep it and remind myself. ❤️

Our depraved techno-wannabe-overlords are bolting all manner of sensors to more and more devices in more and more places. This includes more and more devices that can move and interact in the environment such as cars, drones and humanoids. Rather than learning from the inshitternet, learning and experience will happen in an ever more intimate and experiential way. There will be mechanisms of feedback, and perhaps not self replication, but the aforementioned techno supremos will ensure the replication happens. In time this may lead to self replication – although there may be some limitations that will prevent silicon based technology from scaling to such a degree, or even much more than the current (dangerous) party trick level.

Of all technology, this is perhaps the most fragile, so most likely to fail and disappear sooner rather than later (hopefully), and almost certainly to not have any med to long term prospects.

Do you have any thoughts on how this might play out?

[edited for brevity]

I'm all for the "there are no actual things in reality" idea.

I also get that materialism is mostly about interactions, not particles.

But I wonder if the idea of "interactions" might actually be a problem/"problem" (self-imposed limitation) for materialism. The term "interaction" implies something occurring "between things". Do materialists believe fundamental particles really are (the only) things (albeit inseparable from one another and time)? Or is the idea only that they may as well be treated as irreducible things for anything (including us) that exists in "our" universe, since science/observation/experimentation does not appear to be capable of probing any further?

I also appreciate your "why be greedy?" sentiment, Tom (just be humble and accept the materialist explanation of reality). But, on the other hand, shouldn't we allow science to include thoughtful consideration of the "unknowable" as part of any scientific theorizing (especially if there is potentially stuff that might be fundamentally, not just practically, unknowable)? If we aren't willing to allow "science" to include this, then isn't this itself an admission that "science" may, or is and will always be, limited? I'm not saying a free-for-all, but…

I think it is actually a duty, rather than a case of us being greedy, for us modern humans to ponder the (potentially) unknowable-by-science stuff, not so that we can create and believe in ideas like life-after-death to gain solice from what is happening in the world (bury our heads in the sand), but so that we can avoid any temptation to use materialism (no free will) as an excuse to do nothing. I think we need to *genuinely own* the situation in order to properly commit to trying to do something about it. I think we *need* to find a worldview that does allow for us to have choice/responsibility/obligation, even if materialism claims that all this stuff is an illusion. Perhaps the claim that these things are "ultimately" an illusion is false because materialism is/might itself be limited? I just don't believe choice is an illusion and I think that it is precisely within the domain of the unkowable-by-science stuff that the possibility for real choice/reponsibility/obligation lies.

Regarding sentience, some might find this interesting: https://philsci-archive.pitt.edu/17036/1/Sentience-negative-way.pdf

As far as I am concerned (and many physicists), the electron, down quark, photon, etc. needn't be "where the buck stops." String theory, for instance, replaces all these "different" particles with a loop whose vibrational patterns dictate observed properties/identity. Is it right? We don't know, and perhaps never will. All we do know is that stable nuggets called the electron, etc. have reliably exact properties and behaviors and interactions. It's descriptive, not philosophical. Materialist monism is basically: whatever these doohickies are, there's no reason to conjure anything else to produce all that we experience—certainly no evidence.

Science (as a technique) will always be severely limited in what it can know—largely as a consequence of complexity, but also limited reach in scale, energy, etc. That said, at the scales and energies pertinent to biology (femtometer to galactic), techniques have left very little room at the fundamental particle/interaction level.

As long as you're aware that your take on illusion is pure belief (not evidence-based), that's all fair. Beliefs can run wild. It is my belief that material monism is enough. In this case, though, I can rest on the empirical evidence that it is demonstrably enough in every setting that permits adequate exploration, without exception (not easily dismissed).

Panpsychism does not demand dualism. For example, temperature arises from the complex interactions between atoms. Is temperature a characteristic of the universe? It arises emergently from interactions. So does the proton. Is the proton a characteristic of the universe? So consciousness is an emergent characteristic of the universe. Who says where it can arise and how much complexity it takes? Maybe like temperature or protons it exists emergently everywhere in some measure. Can we determine where it begins? Does it need dna? Seems like saying so is dualistic.

You forgot toenails and snowflakes. Are they a (fundamental) characteristic of the universe? Or are they material arrangements that *can* happen—like protons (from quarks/gluons)? Temperature, as a well-defined statistical account of kinetic energy, is hard to compare to a toenail or consciousness, which each have adaptive benefit in living arrangements.

As per the post, it seems sensing and reacting in the context of self-replication is where one might say consciousness begins to emerge (i.e., not in our contraptions), but the "edge" is surely fuzzy (and irrelevant). Does it need DNA? We're not qualified to say if other material arrangements can accomplish self-replicating organisms. I wouldn't bet against the universe in crafting other ways, elsewhere. I'm not sure how I'm being dualistic (but I was steeped in a dualist culture, so can't rule it out!).

Nice essay! But' what's crucially wrong with with the materialist arguments? Simple. There are only 4 forces acknowledged by science. The electromagnetic force is the only one of molecular organization. And by itself, it cannot explain the phenomena of life.

Our machines demonstrate that the electromagnetic force needs an external structure to perform. It just wants to go and stay in the lowest possible energy level.

The electromagnetic force's properties simply cannot explain its behavior in a living organism. In an organism, there must be an invisible structure to contain and direct electromagnetic force's simple properties of push and pull. .

As to consciousness, Tom simply focuses and the possible physical MECHANISMS that exist in the brain or bacteria, etc. He's locked into Descartes' 17th century view of reality. He takes the operation of MEMORY for granted! The key to understanding is MEMORY!!! Memory provides the structure for all behavior and awareness. The presentism of the material world simply cannot explain memory's hyperdimensional structures, particularly when we look at the innate memory structures that animate insects . That means consciousness too must be hyperdimensional.

For example in the quote below, Tom is ignoring that all industrial machines require an external structure to control the electromagnetic forces that operate them. (and the machine's structure is created by the design and goals of the conscious mind. Machine's don't create themselves!!!) That is the "gulf" between the living and mechanical worlds. That is what materialism can't explain– the invisible structure of "animate fields" that produce and operate the living organism.. . He's really just rehashing the same old, same old arguments that have been around forever.

Tom writes — In other words, accounting for the enormous gulf between living sentience and industrial machines need not be some ethereal “substance” or mind-blowing quantum phenomenon. The universe is quite practiced at piling up the mundane to make something spectacular. If a mundane—but exceedingly complex—explanation is possible (in principle, even if too woolly for primates to actually pull off), why not go with it? More to the point, what stands in the way of the universe from taking that readily-available path whether it suits our preferences or not.

For more, see https://www.carlgunther.com/

Lots of bold assertions and presumptions here about what cannot be possible in the universe, mixed with what appears to be general unfamiliarity with electromagnetism—which for instance holds water molecules together and runs weather without requiring this external structure. As for memory, our stupid inventions have no problem preserving memory, nor do the mountains and rock layers themselves. Not really an un-leapable chasm between material and memory preservation. It is correct that self-replication is a huge feat our stupid machines are woefully (thankfully) incapable of replicating. But that trick need not require something beyond material interactions.

Hi Tom, Thank you for this series of posts. I have learned a lot about consciousness and language, in particular. It is quite revolutionary for me to place my own sense of me on the same dodgy ontological footing as that of 'God'. It is quite liberating.

I think it is really important for us modern humans to recognise that when we say “my mind” or “my consciousness”, the “my” bit is actually shorthand for “the universe’s”. Each of “our” consciousnesses is really ultimately the universe’s, just from a different perspective. There is no “us” separate from the rest of the universe (“our” free will/choice is the universe’s free will, or an allocation of it, in my opinion). We humans are not the only conscious things, and perhaps every single thing in the universe – representing a unique perspective of the universe – is “conscious” in some way (I think that everything has a degree of self-awareness and has a “creative will to move”, i.e. “spirit” in the purely animist sense). None of us are individually the whole universe and none of us are the absolute centre of the universe. But we (and every single other thing in the universe) are each the *whole universe from a unique perspective*.

I think mind and consciousness should really be framed more generally in terms of a “will to move/create” and “self-awareness”. These things get talked about as though they are “higher order” consciousness, and that things like sensations of colour are “lower order”. I think this is wrong. I think will-to-move and self-awareness are the absolute fundamentals of “consciousness”/“mind”, possessed by everything. I think that these things, together with physical space and eternal time, are the absolute fundamentals of the universe. The rest, including the “fundamental” particles and the “fixed” laws of physics, are what the universe created (and forever continues to create) out of itself through a *genuinely creative* process (not just creation by “handle turning”). The universe is the continual creator and creation. As far as I can see, if one does not believe this is the case, then one must at least acknowledge that the only other options are that there is a truly separate creator of the universe (God), or that *literally nothing* created the universe at some point (either the Big Bang or some previous point) and is ultimately responsible the “movement” and things we observe in the universe – the unfolding story since the start of the universe). Are there other options? A belief in a separate God or a belief in the “power of nothing”. I prefer to believe that the universe is literally everything, has always existed and is genuinely creative.

It's far beyond my pay grade to make up stories about what the universe truly *is*, so I try to stick to what it *does* (and what it needs to accomplish what it does). I don't believe we'll ever know why there's something rather than nothing, so stories are appropriate to fill in the blank (ideally, acknowledging that they're just stories made up in meat-brains).

As for why the particles and interactions we have are what they are (which, BTW, have not appeared to change from a fraction of a second after the Big Bang until now, based on how things froze out), that, too, we can't know. But multiverse (string landscape) ideas at least paint one way this *could* play out, in which case the properties that "our" particular universe exhibits are no more fundamentally significant than the exact shape of a shard of broken glass. It came out the way it did (and other universes have their own unique characteristics/physics), and that's that. No deep mystery, but naturally beings like ourselves require certain conditions, bringing about a selection effect. We don't look for the deep coincidence that puts alligators in swamps instead of on desert mountain peaks. It can only be the one way.

To me, the story of the universe (which is the universe) is the continual creation of new, unique viewpoints of itself, which creates meaning within the universe. Depth of meaning increases the more the whole system consists of a diverse range of “viewpoints” (“things”) that are able to mutually accommodate/tolerate/respect/appreciate the existence of other viewpoints/things (that’s the lesson I take and generalise from the evolution of life on earth at least). I think the universe does the best it can in seeking to create a “harmony of existence”. It is obviously a learning process – a self-learning (autodidactic) process – for the universe, with mistakes made along the way. We modern humans have access to a teacher/guide though: life on earth. We need to stop going it alone.

It's totally fine for us each to have our own stories, realizing that stories are not constrained to line up, be compatible, or represent truth. To the best of our knowledge, the universe will continue to expand (accelerating at present), stars will run out of fuel, Life will wind down, and whatever "self-awareness" once went through a mounting phase will experience a dwindling to inactivity. That's all fine. We can appreciate and enjoy the time we're in. But narratives of some purposeful drive toward awareness may be nothing more than stories to make *us* feel special (rather than appreciating even a lifeless universe as amazing and special, for instance). Pesky dualism again.

Just to clarify/better express myself, when I say “I believe this is what the universe fundamentally is…” I really mean “This is what I believe to be a metaphorical truth about the fundamental nature of reality…” (whilst acknowledging that I could be completely wrong).

I respect materialism, but the more I think about it, the more I see it as being restricted to being an accurate description of our observable universe – perhaps the best we will ever achieve – and not a (complete) attempt at presenting a metaphorical truth about the entirety of reality/existence, because there is surely “more to it all” than just materialism (no?). There is stuff that we just don’t know and never will. That said, I don’t think it is beyond our pay grade to attempt to come up with a metaphorical truth about reality, though it is certainly above our pay grade to claim knowledge of the absolute truth. I think coming up with a metaphorical truth about reality might be key to us learning to live truly well on this planet (again). I think animism was/is such a metaphorical truth. I personally don’t see why we can’t learn to view the world in this way again, with “spirit” running through everything – genuinely creative spirit.

But…. I may be being too harsh in claiming that materialism isn’t optimal as a worldview (for humans). It clearly works for many, including you, Tom. It works for me as a worldview some days, but not completely on others (maybe my more dualist days…). I really appreciate your efforts to draw links between physics and animism. I just feel that I need a genuine sense of purpose and obligation that meshes with life continuing on this planet (in all its magnificent diversity), and for that purpose to be *real*, not just a desire for me (even if it isn’t real…).

I personally think we modern humans desperately need to have natural totems again. It gives us a sense of obligation and purpose that we need, in a way that is compatible with the ongoing existence of ourselves and life in general on earth. It naturally removes our focus from just ourselves and opens our eyes to the interconnectivity of everything, but in a way that is more “relatable” to us as humans.

I'm glad that at least you are wrestling with (and acknowledging) dualist tendencies. It seems you've had at least partial, temporary success at monism (until the inner voice demands greater understanding than materialism allows). No one can claim that the universe is "more than" materialism, but that falls far short of knowing everything: the complexity is too overwhelming.

It is also appropriate to fashion stories that we *can* handle and engender ecological viability. Animism is such a stance. I could easily make the case that we were better off as a species within the Community of Life as humble animists: certainly better than as modern dualists. I'm excited that materialist monism (only possible via discoveries from a dualist culture) illuminates a path that isn't overtly contradictory to animism, even if traditional animism did not put things in modern materialist terms. What I seek is an off ramp. If you don't reject material reality and matter/physics, but wish to ditch dualism and forge a path toward animism, here is a possible path. In 10,000 years, perhaps we will not need the off ramp any more, and can happily live in a more ignorant metaphorical "reality" but without destructive dualistic traits (we are all one: sun, rocks, weather, dirt, microbes, fungi, eagles, etc.). For now, I am pleased to explore the off ramp.

At last we come to it: the elusive search for the divine spark, the animating force, the immutable soul lurking behind or within the self. Your contention that it’s a piling up of complexity lying beyond comprehension, all attributable to material interactions, calls to mind Dennett’s discussion of cranes and skyhooks (the latter being unnecessary to explain things, at least in principle). Well and good enough, unhappy though that perspective may be. It’s a pretty severe downgrade from stories we tell ourselves (about ourselves).

I struggle with your defined terms while acknowledging language smuggles in judgments about hierarchy and supposed superiority. Still, I prefer not to collapse disparate categories into larger categories using the same term. For instance, a machine (an invented, manufactured item) is not an organism. Similarly, though mankind is situated within nature and the universe, to assert all is therefore “natural” excludes “unnatural” and “manmade” from the lexicon, which I find unhelpful.

Two items you have not addressed I would like to see (no doubt my own hangups): (1) the role of recursion that raises sensing and responding to self-awareness and (2) the radical discontinuity between multiple scales in physics extending from subatomic to cosmic. It’s all material but operative dynamics are discrete enough that questions of life and sentience really only occur at the scale of Newtonian objects unless one is some sort of universalist.

It is certainly true that the items we normally call machines (manufactured) are not very much like what we normally call organisms (evolved forms). Most important is what they *do* (and don't do) rather than what we label them.

Perhaps we can blame the dualists for suggesting the sweeping comparison in the first place: their reaction to the suggestion that life has a strictly material basis is to reject the notion on the grounds that humans are not machines. See: they made the big sweep. My tactic is to question and remove the asserted ontological gap, and one route to that is to de-fang the labels as carrying ontological authority. Loosen our grip on what "machine" signifies and lots of new associations become possible.

I'm not satisfied with yoking definitions to activities. An old-school cash register, a computer, an LLM (a "brute force parlor trick"), a neuron bundle, and a brain are each and all information processors. That's what they do. Yet they're light-years apart in connection with the questions under consideration.

Fair enough. I suppose I should amend my "what they do" with "what they do, in their entirety" rather than one slice/aspect of their total behavior in the world. The light years come across when all "doings" are considered.

Tom – in a nutshell, the videos beautifully depict the fantastically organized molecular motion in a cell. But what produces and sustains the perpetually organized microcurrents within the cell that carry each molecule to exactly where and when it needs to be? The theory of emergence is an observation, not an explanation.

What produces the exact same patterns of form and force that drive molecular motion and interaction with mechanical regularity for millions of years? As Schrodinger explained, the properties of the electromagnetic force can't explain it. There is a vast invisible structure that science refuses to acknowledge.

Anybody who could offer convincing evidence of these claims would be famous. Of course, they'd need to somehow convincingly counter mountains of studies of these fascinating and captivating processes that—believe me—have attracted plenty of attention as to how 3D molecular shapes and forces are able to manifest these actions. It shouldn't be surprising that at first glance these mechanisms elude comprehension (ignorant meat-brains), but it's a *very* tall order to demonstrate the inability. Loads of detailed analyses have illuminated the how of this or that part of the process, and nothing yet is outright implausible. In selecting incredulity vs. awe, we need to assess whether we have the mastery/authority to say what's not possible when we're over our heads in complexity. No human holds such claim—especially someone like Schrödinger, who died before molecular biology had gone very far.

"How can sentient living beings possibly arise from matter alone?"

This could be because matter itself is conscious. An electron is observed to be attracted to positively charged bodies – one might say it chooses to move towards them, just as it chooses to move away from negatively charges bodies. (Of course, scientists would not say the electron "chooses" its path – but how do they know?)

"Microbes sense and react to the conditions they encounter, as do spores, sperm cells, seeds, plants, fungi, and animals."

In the same vein, why stop at microbes? The reacting may continue down to molecules, atoms, electrons and so on.

You compare the tech we manufacture to organisms, but maybe our machines are an *abuse* of matter in some sense. I.e. matter left to its own devices organises itself into Life, in contrast to the inanimate machines that are the unnatural arrangements humans force it into.

This self-organisation is the hallmark of Life, in complete contrast to machines that require some external agent to build them. Sentience informs Life from the smallest atom to the largest animal. That's why organisms *want* to exist but machines do not. It's not just a question of complexity, but of the method of 'construction'.

Indeed electrons react, and cannot choose otherwise: exact compliance. Rather than extend dubious dualist notions of consciousness down to the subatomic level, it is also possible to extend the "forces made me do it" scheme all the way up to stars, snowflakes, and animals (all of which self-organize). Oh, and speaking of self-organizing machines, a nuclear fission reactor (Oklo) self-assembled 2 billion years in Africa before humans tried their hand. The lines are not as crisp as you make them out to be. "External agent" is another echo of dualism: some motivating agent apart from material interactions.

Ok then, self-organisation and replication are the hallmarks of life. The Oklo reactor self-organised only as much as, for example, a whirlpool or waterfall does. It had no wish to do so, and it has no ability to replicate itself (nor does it want to). So it is not Life – it did not form with any purpose or goal. And nor is it a machine – there is no task it was designed to carry out. It's a natural, non-living formation, like a star or a snowflake.

The point is that machines do not self-assemble/replicate in the way Life does – they *do* require an 'external agent' to design and build them (dualism is not relevant to this point).

Maybe organisms utilise the proto-consciousness that all matter, including at the subatomic level, has? Just as with a bat, there's no way to know what it's like to be an electron without actually being one. Perhaps outcomes that quantum experiments attribute to 'chance' could be attributed to 'choice'?