Two weeks ago, I described my factor-of-five reduction of natural gas usage at home, mostly stemming from a decision not to heat our San Diego house. We have made similar cuts to our use of utility electricity, using one-tenth the amount that comparable San Diego homes typically consume. In this post, I will reveal how we pulled this off…with plots. Some changes are simple; some require behavioral changes; some might be viewed as outright trickery.

Two weeks ago, I described my factor-of-five reduction of natural gas usage at home, mostly stemming from a decision not to heat our San Diego house. We have made similar cuts to our use of utility electricity, using one-tenth the amount that comparable San Diego homes typically consume. In this post, I will reveal how we pulled this off…with plots. Some changes are simple; some require behavioral changes; some might be viewed as outright trickery.

Measurement and Data

My several-year journey started—as it often does for me—with measurement and data. Utility bills are the best starting point, accumulating the number of kilowatt-hours used in a month. This information is certainly useful as a baseline against which to judge future improvement. But how do you know when you’ve got a reasonable footprint?

One answer is that the average American household uses about 30 kWh/day of electricity—implying a constant burn rate of 1200 W. To get a more representative number, some utilities provide an online comparison to similar houses in your area. For instance, I can compare my usage to that of single-family homes built before 1977 accommodating 1–2 people, having no swimming pool, with or without air conditioning, and can enter my house’s square footage (a.k.a. area). In San Diego, these parameters result in a yearly usage of 7458 kWh and 6317 kWh with and without air conditioning, respectively. This translates to 17 and 20 kWh/day—predictably lower than the national average, but not by as much as a factor of two.

When I first took stock of my energy usage in 2007, my wife and I totaled 3466 kWh in a year in a condo without air conditioning. The equivalent apartment/condo total for San Diego is 5312 kWh. Already, we used 35% less electricity than typical area residents. (We were right on the nominal amount of gas usage, at about 300 Therms per year.) Lately, we use something like 750 kWh of utility electricity in a year: almost a factor of five reduction for us, and about a factor of ten less than the equivalent San Diego household (our house does have air conditioning installed).

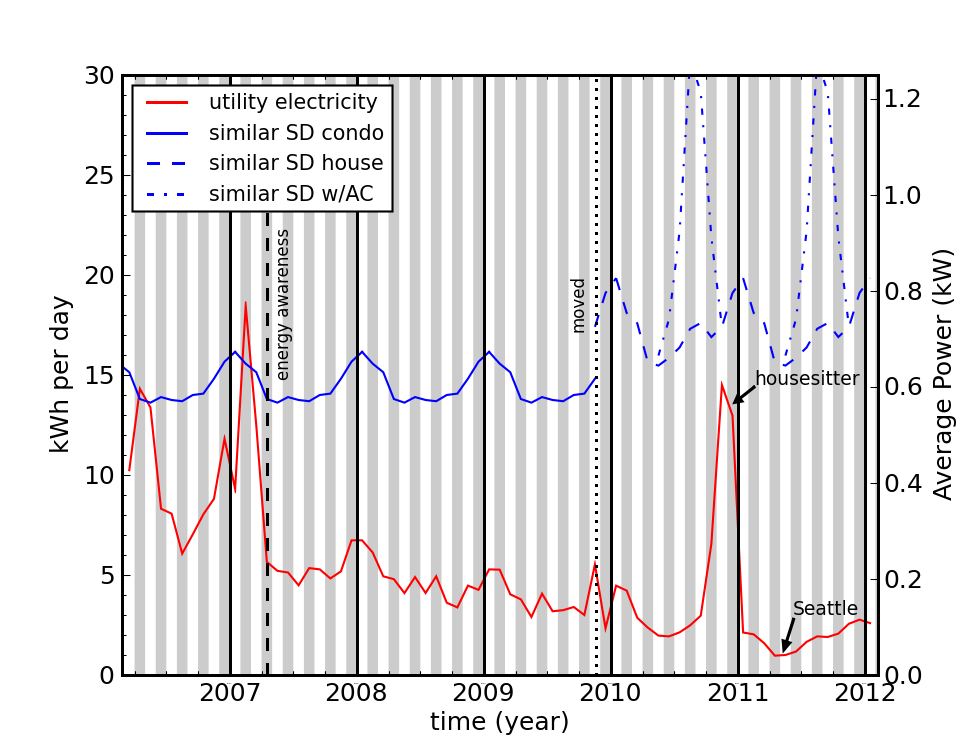

Above is a plot of our electricity use over time as we migrated into energy awareness and also moved from a condominium to a house. Alternating gray and white bars represent months within the year. Electricity use of typical San Diego condos and houses matched to the ones we occupied is shown in blue—including two curves for houses with and without air conditioning. Our (red) curve was once roughly comparable in scale, but has edged downward over time due to a variety of changes. A house-sitter in the latter part of 2011 blew our trend, probably by befriending our space heater. But this deviation serves to illustrate the importance of people and behaviors over the physical house.

Above is a plot of our electricity use over time as we migrated into energy awareness and also moved from a condominium to a house. Alternating gray and white bars represent months within the year. Electricity use of typical San Diego condos and houses matched to the ones we occupied is shown in blue—including two curves for houses with and without air conditioning. Our (red) curve was once roughly comparable in scale, but has edged downward over time due to a variety of changes. A house-sitter in the latter part of 2011 blew our trend, probably by befriending our space heater. But this deviation serves to illustrate the importance of people and behaviors over the physical house.

Okay Mister; What’s Up Your Sleeve?

You can always tell a physicist from a magician, even if both show tricks/demonstrations in front of an audience. The physicist is eager to explain how and why the “trick” works, perhaps repeating the performance and encouraging onlookers to view from all angles. So I can’t wait to tell you how we pulled off this fantastic reduction.

But first, let me reveal two of the items I do have up my sleeve. The first is the Kill-A-Watt electricity metering device (see note at bottom). Anything that can plug into the wall (and that consumes less than about 1800 W of power) can be measured with the Kill-A-Watt. It displays instantaneous power, in Watts (my favorite unit); accumulated energy, in kWh; and the time over which the measurement is accumulated. Because I have a Kill-A-Watt, I know exactly how much my laptop uses as a function of screen brightness, when charging the battery, when “sleeping,” and the impact of leaving the power supply plugged in without the computer around. I know how much standby power my various appliances use. I know how much my cable modem and wireless router consume 24/7. I know all about my refrigerator, television, lamps, alarm clocks, printers, etc.

The second tool is my friend TED, who I have known since November 2011. I met TED when I was temporarily living in Boston, and took him as an uninvited guest to join friends in upstate New York for Thanksgiving. TED is also known as The Energy Detective, and my grad-school buddy was as eager as I was to rip into the packaging and install the device in his breaker box. Soon enough we had real-time readings of his whole-house energy consumption. It was Thanksgiving evening, and the kitchen was busy with preparations. The “kids”—young and old—delighted in running around turning on and off various lights and appliances to gauge their effect (and the corresponding real-time graph change on the laptop). Our hostess became increasingly irritated by “outages” of light in the kitchen and by our wails when the oven kicked on pumping kilowatts of power into the turkey. Fed up, TED was asked to please leave the premises: back in the box. My wife sympathized with our hostess and I feared that TED may not even find welcome in our house when we got back to San Diego.

Besides the Thanksgiving fiasco, my wife was reluctant to have yet another data-gathering tool in the house. But TED now does live at our house, and has come to be accepted as a member of the family. Indeed, my wife was not a big fan at first, but after a few weeks I found (and kept) a note sitting by the display saying, “Okay, TED’s pretty cool.”

What do these “trick” devices have to do with reduction of power consumption? Knowledge is power. And knowledge of power is spectacularly useful. We got rid of wasteful devices like a stereo that had an inexcusable 12 W standby power drain (9 kWh/month). Knowing the power associated with various lighting choices guides our decisions about what lights we might want to use and when. We have identified various phantom loads (devices that suck “standby” power without providing benefit) and eliminated them by unplugging when not in use. These include a 9 W pull from the printer even when off; 11 W from the central air circulator that we were not even using; 5 W from the sprinkler control that we also were not using; and others as well—you get the idea. Some countries have on/off switches at the wall outlet to make such savings simpler to effect.

Killing Phantoms

One of the most important reductions one can make is reduction of baseload power: devices that consume energy 24/7. Every 1 W eliminated removes 9 kWh from the yearly tally and about $1 of yearly cost at nominal electricity prices. Each constant Watt removed saves as much daily energy as one minute of microwave oven cook time (one Watt times 24 hours is the same as 1440 W times 1/60th of an hour: 24 Wh). Constancy is the killer here. We’ve reduced our utility baseload to about 40 W continuous from an initial 100 W or so. That’s about equivalent to the total utility electricity we use now. It can be a big deal.

Lawrence Berkeley Lab put together a useful table of standby power for a number of appliances/devices. Standby power is estimated to consume about 10% of residential power in the U.S. Since the typical household uses 30 kWh per day, this means phantoms slurp 3 kWh per day per household, amounting to 125 W of continuous drain per household, and 14 GW of power production nationally. A dozen super-sized power plants to do nothing.

Imagine that we assign specific tasks to power plants. We have the power plants assigned to lighting applications. There are a goodly number of power plants assigned to running televisions. We’ve got the hair dryer power plants—fewer now than in the big-hair era of the 1980’s. A worker at any one of these plants may feel proud to provide essential services to fellow citizens. Then you’ve got your dozen standby power plants. Imagine the morale at one of those plants: Wally working hard all day, coming home exhausted. But because of poor Wally, our printer could sit doing absolutely nothing and slurping power all day. He really doesn’t deserve the nickname Wally Wall-Wart (after the name given to plug-in transformers), because it’s our own silly habits and inattention that make Wally go in each day to keep the plant thumping.

Monitoring Baseload

The deluxe way to monitor baseload is with TED (see note at bottom). One productive trick is to turn off one breaker at a time during a quiet period and see which ones host standby power. From there, the specific culprits can be tracked down. A far cheaper solution is the Kill-A-Watt, which can at least tell you about the items that plug in to the wall (almost all phantoms are of this variety). But you can also use the utility meter already attached to the house to measure baseload power.

Analog utility meters have a spinning disk that completes one full turn per unit energy increment. The energy increment is called the Kh value, printed on the meter, and often 7.2 for residential meters, or some multiple thereof. The Kh value corresponds to the number of watt-hours per turn. If your dial takes 360 seconds to complete a full turn when the house is quiescent, 7.2 Wh per 0.1 hours means 72 W. A 90 second turn means 288 W and you’ve got work to do! In general, the power under the meter’s purview is 3600×Kh/T, where T is the dial period in seconds. Surprisingly, the disk rate can vary by a factor of two in a repeatable/cyclic way even when the power is constant. So it is important to measure one complete cycle. If it seems to take ages to go all the way around, good!

Be careful that the refrigerator is off for the measurement. Run out the door right when the fridge shuts off for the best result. If the number does not make sense, try again later: maybe something was stealthily on, like the refrigerator in a quiet defrost cycle.

Digital meters eliminated the disk. It is infuriating to me that the meter internally measures the instantaneous power—it simply accumulates this to arrive at an energy measurement—but this value is not presented to the homeowner. It’s arguably the most useful measurement a power meter can supply, yet it’s just simply absent. I spent hours on the phone with my utility company trying to understand how I might access this information. I ended up spending most of this time patiently explaining that kWh and kW are not the same thing, and a time or two found myself discouraging erroneous use of the unit: kilowatts per hour. In the end, I learned that the digitally simulated disk (little blocks that appear and disappear) carry the meaning that each appearance/disappearance corresponds to the passage of 1 Wh. For me, this means that one complete cycle of the three-block pattern is 6 Wh. For very slow rates, I can measure just one block. For instance, at my house it takes 94 seconds between the appearance of consecutive blocks, computing to 38 W. For 1 Wh blocks, Kh = 1, so standby power is just 3600/T, where T is now the time for one block. I do not know how universal this behavior is, but I suspect it is relatively reliable from place to place. I note that my meter has 1.0Kh printed on it, which I’ll bet means one block equals 1 Wh. So look for something like this on yours as well.

Lighting Replacement

An easy move to reduce electricity consumption is to switch to fluorescent or LED lighting. These typically consume one-quarter of the energy that incandescent lights do for the same level of light output. If a house uses 1000 W of incandescent lighting for six hours of the day (6 kWh), then the same practices using efficient lighting consumes only 1.5 kWh and therefore reduces the typical American house’s electricity usage by 15%. I’ll take it.

Incidentally, You can buy a 100 W incandescent bulb for about $1 that will last 1000 hours. Or you can spend $5 to get a quality compact fluorescent light (CFL) that will last 10,000 hours (don’t spend $3, or your CFL may not last long). Over the same period, you would need to buy 10 incandescent bulbs for a total outlay of $10. But that’s not the worst of it. In that 10,000 hour period, the incandescent bulb racks up 1000 kWh of electricity, costing about $100 at a price of $0.10/kWh. Meanwhile the CFL sips power at 25 W and will cost $25 in its lifetime. In either case, the electricity cost dwarfs the hardware cost. In the end, you can spend $110 for incandescent lighting (and nine bulb changes) or $30 for CFL lighting of the same intensity. Yet many people huff at the $5 CFL cost (and as a result may get cheap versions that don’t last so long and turn them off further).

Behavioral Changes

Killing baseload and changing lights can have a substantial impact on electrical energy used. But behavioral adjustments can be equally important. Behavioral changes stem from changes in attitude or values. Treat electricity as precious, and you’ll find yourself using it more frugally. Here I will describe some of the adaptations we have made to cut our electricity usage.

First, we started line-drying our clothes to avoid using a 5 kW power hog, totaling something like 5 kWh per use. We are sparing launderers anyway, averaging something like a load per week (involves multiple wearings of outer garments between washes). We pay attention to the weather and jump on the sunny days to get the laundry done. I’ll note that in many European countries, people don’t even own clothes dryers. For instance, after drying our hiking clothes outside when visiting a friend in northern Italy (more like Munich than Sicily), I was even more impressed when we went to visit a well-established physicist in a large house who had laundry hanging out in the yard. If they can do it, so can we! When our electric dryer at the condo—which at this point was used for storage—turned out to be incompatible with the new house (rigged for a gas dryer), we simply went without. Just like our friends in Italy, we own no clothes dryer. We’re fine.

We learned that our neighbors were looking for a refrigerator, so we gave them our deluxe side-by-side unit (which we had bought for $50 four years earlier on Craigslist), and swooped up a slightly smaller, used, simpler fridge with freezer-on-top. The old fridge averaged 75 W of power draw (typical of modern large side-by-side), while the new one is half of this. This move saves about 1 kWh per day. Even though our old fridge continued to run somewhere, redistributing used refrigerators does save the substantial embodied energy of new appliances—as long as the old refrigerator is not a total hog by modern standards.

We also became far more vigilant about not leaving lights or devices on when not in use. It’s not unusual for an American house to be “all on” in the evening: daylight throughout the house. But light switches are conveniently placed near the doors of every room, so it’s really not much of a bother to keep lighting where you are, and allow darkness to rule where you aren’t. Part of this training/awareness derived from an experiment to make our living room off-grid using solar panels and batteries. We treated our harvested energy as precious, and did not dare leave the television or living room lights on when we were not using them. Energy became very personal, and this attitude transferred to the house as a whole.

The Big, Sneaky Trick

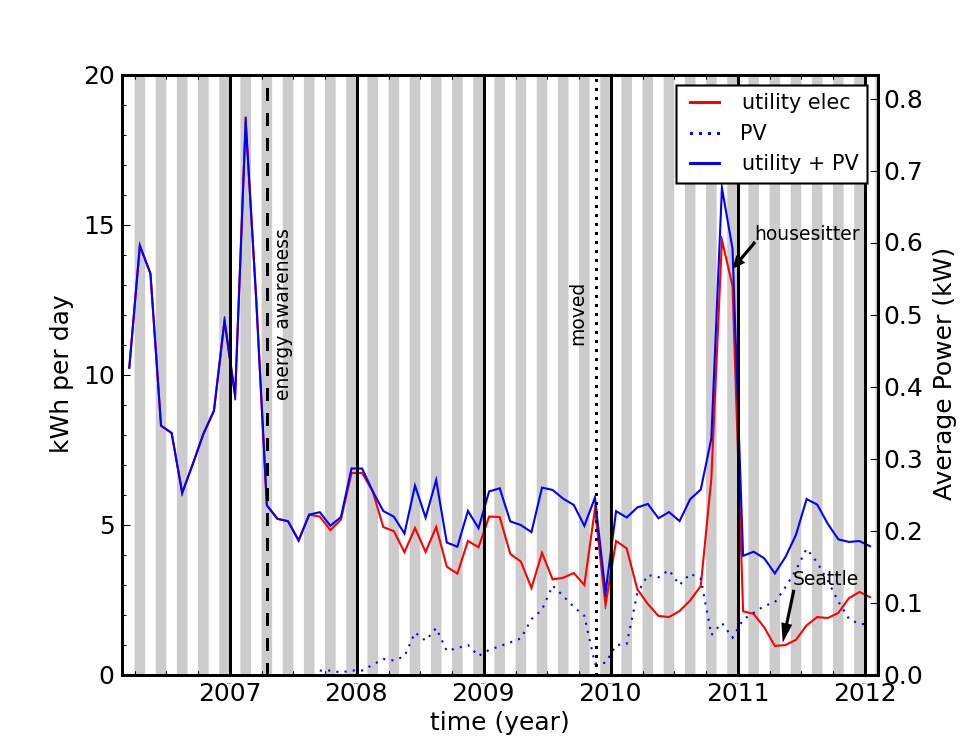

The plot above of our electricity use over time shows a progressive decline year over year (ignoring the house-sitter contribution). Some of this is indeed due to all the reasons mentioned above. But I left out a key piece. The living room solar experiment started out as a single 130 W panel for the television/DVD/stereo and a 64 W panel for the lights—as described in an article I wrote for Physics Today in 2008. But over time I kept upgrading the system—adding panels and batteries. Before I left the condo, I was up to 6 130 W panels and two golf-cart batteries. After we moved, I bumped up to 8 panels and 4 batteries. The combined effect is shown in the next graph.

The red curve is the utility electricity shown before, but now the solid blue curve is the combined utility and photovoltaic (PV) energy delivered to appliances within the house. So really we stabilized at about 5 kWh/day. Still, this is about a factor of four lower than the typical San Diego household of similar size and occupancy.

The red curve is the utility electricity shown before, but now the solid blue curve is the combined utility and photovoltaic (PV) energy delivered to appliances within the house. So really we stabilized at about 5 kWh/day. Still, this is about a factor of four lower than the typical San Diego household of similar size and occupancy.

Note the step reduction at the start of 2011. This coincides with the arrival of TED at my house, through which I discovered some extra phantoms and killed them. The summertime tends to draw more electricity to run an attic fan, but the fan is driven by the PV system—a great match, by the way.

Looking back at the period before “energy awareness” arrived, The winter-time electricity usage looks suspiciously like the gas profile from the post two weeks ago. At first I imagined that the electricity used to run the furnace blower may be to blame. But closer inspection suggests that this is not the case. A typical furnace in the U.S. may consume somewhere between 50,000–100,000 Btu/hr of energy, which is 0.5–1.0 Therms of energy per hour. Meanwhile, the blower may operate at something between 500–1000 W. Therefore, each Therm expended in the furnace may be accompanied by anywhere from 0.5–2 kWh of electricity to push the air around. Direct measurements in my current house land right at 1 kWh of blow-energy per Therm burned. Consulting the gas expenditure plot from a few weeks back, we find that the winter peak in gas added no more than about 40 Therms per month of gas use, or 1.3 Therms/day. So I might expect no more than an extra 2.6 kWh of accompanying electricity use per day: nowhere near the extra 12 kWh/day we seemed to use in February of 2007. Other adaptations must take the credit.

Where is the To-Do List?

I have offered examples of the things we have done to shave energy use. But I held back from making a list of things you could/should do on your own. If I have one piece of advice, though, it’s to start measuring your usage. Information is the key. Once you know where you are, and start gauging the effects of various options, you’ll make your own list. Then you’ll own your improvements.

The Combined Effect

We have made substantial (factor-of-five level) reductions in our use of household energy on both the natural gas and utility electricity fronts. For a house matching our size, occupancy, and vintage in our area, we now use one-sixth as much natural gas and one-tenth as much utility electricity as is typical (one-eighth the electricity if compared to houses without air conditioning). The ratio for electricity is closer to one-fourth if including our solar-generated electricity. Even so, it is clear that our behavioral choices have resulted in a dramatic reduction of our energy demands. This is far more powerful than the usual trimmings at the 10% level.

We learned that some new friends, who live a modest lifestyle in a small condominium, somehow got word that my wife and I are efficient livers. But when they found out that we live in a somewhat more expansive house, they suspected the rumor could not be true. This developed into a challenge to compare utility bills. Game on. Their implicit assumption was that a larger place meant greater cost to heat and cool. But if you do neither, the extra space comes with no recurrent energy cost. As long as the activities within the house are not wasteful (via lighting vigilance; phantom-intolerance), there is not much correlation to house size and energy consumption.

Most of our societal energy is consumed outside of the household—it’s true. Therefore, some might argue that even eliminating household energy use would only put a small dent in the overall picture, so why bother? Three answers to this (obviously, I do bother):

- Household energy is under your direct control: exercise what control you have, rather than expecting others to make changes elsewhere.

- The biggest shift is one of attitude toward energy. Adopt a different attitude about the value of energy in your home, and I guarantee this will have ripple effects beyond your household gas and electricity use—it’s just the beginning.

- I have not stopped there. Stay tuned to future Do the Math posts about the many other ways I have been able to shave energy use beyond the home.

The point of all this is that reduction of energy demand is perhaps our most powerful, near-term weapon in facing a world of increased pressure on energy supply. Price signals may ultimately push us into these adaptations, but why not see it coming and be ahead of the curve?: one step ahead of the neighbors. We are a culture adapted to the expectation of growth: more tomorrow than today. This attitude will fail when it comes to energy—starting with liquid fuels. Reduction is a way to beat this physical reality to the punch, and at the same time offer enough relief that maybe we’ll have enough surplus energy (and political will) to build out a modest energy infrastructure less susceptible to the resource limits we face.

There I go again—pretending that we might have a smart, adult response to the problem. But let’s try it, hey. Maybe it’ll catch on. And even if not, our neighbors will look to us for guidance when they can no longer afford their current practices.

Note: I am in no way advocating specific consumer products or brands. I simply report on my limited experience with a few products that have worked for me. I receive no perks from associated companies or vendors.

Views: 15646

Perhaps the right way to sell people on CFL and LED bulbs (the ones that don’t suck and/or die early) is demonstrate that there is no investment available that pays at the rate of replacing a filament bulb with one of the more efficient ones. My wife is Not Happy about the color rendering (and initially dim light) from CFLs, so I spent $32 (tax included) on an LED bulb (recent provenance, checked lumen ratings, etc) from Home Depot. CRI is better, comes on instantly. Claims to be dimmable, but reviews say, not so much, but I’m not running it on a dimmer.

Bulb comes with a 5-year limited warranty (but I neglected to save the receipt). IF the bulb only lasts 5 years, if it only runs 6 hours per day (= 10000 hours of use, half what is expected), and paying $.15/kWh, the savings pay off its purchase price as if it were an investment (a mortgage, paying back both interest and principal in equal-sized monthly payments) yielding 44%. Tax-free, since it’s savings, not income.

Anyone planning to do this, be careful not to buy those crappy bulbs made of a zillion tiny LEDs. You want the newer ones, and if you’re not sure, spend the money to get a brand name (e.g., Philips — which is cheaper anyhow, than the “EcoSmart” flood that I got).

I’ve been meaning to try the same analysis for other energy-saving choices, not sure anything else pays off as well. (E.g., cargo bike + lights, $2000. Variable cost per driven mile is $.19, variable+fixed is $.51, from IRS figures. 2500 mi/year, variable cost, is $475, V+F is $1275. Bike has both costs of operation (tires/chain/cogs, principally) and non-transit benefits (no need to spend money at the gym, or health care costs avoided if you didn’t have time for the gym), but those are more of a pain to calculate.)

At least in the Phoenix area, solar PV has a payoff time of roughly seven years; if you remember the rule of 70, that’s a 10% rate of return.

I challenge anybody in this economic climate to find a safe investment that pays 10%.

Cheers,

b&

“I challenge anybody in this economic climate to find a safe investment that pays 10%.”

To be comprable, you need to have some confidence that the solar panel and all the associated gear are going to last quite a while.

If you have a very high confidence that the gear will last for 14 years, then you will double your money and truly enjoy a 10% investment. However, if the gear blows up after 7 years (unlikely, but bear with my Gedankenexperiment), then you’ve done nothing but recoup your original money, sans inflation.

That said, solar panels in sunny places with high utility bills do make sense, and that business is growing and doing pretty well.

Correction, if the gear blows up after 14 years, then it’s a 5% return. At any rate, since the original investment is lost, the “payback” time can’t be easily translated into an investment vehicle they way you think (not unless you can resell the solar panel installation for the original amount, which you can’t). But the current ultra-low interest rate environment makes solar panels on the roof smart for many people, as you say, just not as good as you think.

Here’s something else we’ve done in our house: motion sensors. And like CFLs and LEDs, they are not all created equal.

One of my pet peeves is lights left on for no reason, anyone with teenagers will know what I’m on about…. so I installed motion sensors in places where the lights don’t need to stay on for more than reasonably assessable lengths of time; the sensors can be programmed to leave the lights on for different period lengths.

The one that took the most perseverance was the kitchen (which now boasts 3 x 5W LED light globes). Rather than merely using a motion sensor, I wanted a presence sensor, because one thing I hate about badly done sensing like this is the lights going out when you still want them on! So the presence sensor I ended up using ($36 at Bunnings, Australia) is set for 5 minutes, but senses for motion every 3 minutes, and therefore leaves the lights on for as long as someone’s moving around cooking dinner. Once dinner’s ready and the meal has been moved to the dining table, the lights go out.

Everywhere else I used cheap sensors, one in the walk in pantry, two in the corridor (which come on in a staggered fashion as you walk down the corridor!), one in the toilet, one in the bathroom, and one on each of the porches….. anytime we have overnight guests, they rave about not having to look for unknown light switches in the dark.

I did a similar study of my apartment’s energy use as compared to my neighbors. Since we were all in the same size unit with the same insulation, direct comparisons were possible (although there are effects as to whether one’s apartment is equatorial-facing for solar heating and also the floor the apartment is on due to heat rising). Every month, I read my meter and that of everyone else.

I don’t have the data with me right now, but the difference between our unit and the others was staggering. Only one other unit was close to our low electrical use, and the residents were workaholics who were almost never there. The other units used 2-3 times as much electricity depending on the season (unfortunately, everything in my apartment complex is electrically powered: including the heater and water heater). During the summer you can hear the other apartments’ central air conditioners running and you can get a good idea of behavioral differences. I’ve even had neighbors who had their ACs running when it was 60 F at night. They could have easily opened some windows to cool their apartments for free.

The main things we changed to lower energy consumption were:

-Turning down the set point on the electric water heater from ~140 F to ~110 F

-Lowering the set point to 63 F on the thermostat during heating months

-Raising the set point on the AC to 80 F during the few days per year that “required” AC (The house rule is that it has to be over 90 F outside. This is in humid New Jersey summers. For cooling we use the suck and blow technique: air is sucked into the apartment on the southwest side and blown out on the east side during the night, then the windows and blinds are shut before the day heats up and the apartment stays fairly cool most of the day.)

-Buying a laptop instead of a desktop computer (I acknowledge that a computer takes tremendous energy to manufacture, but I was going to get a new one anyway due to obsolescence)

-Switching from a CRT to an LCD monitor on the other computer

-Enabling energy saving settings on computers (screen off after 5 minutes of inactivity, sleep mode after 15)

-Keeping (CFL) lights off when not in use (leaving lights on when leaving the room was a bad habit my wife picked up in childhood; her parents are still bad)

At our best we were at about 10 kWh/day for all household energy use (since we’re 100% electric). Then we had a baby and we can’t keep the apartment as cold in the winter or as hot in the summer.

OK, now I have the data: http://imgur.com/a/imbr4

The first image is my electricity use since August 2004. Each color is a different place I lived. The first year had low electricity use since the heat was from a building boiler. The second we had to pay for heat, but it was on the top floor of a newly-built four story building. The green trace is my current apartment, on the second floor of a two story building, facing south (in the northern hemisphere). The triangles are a 12 month moving average.

The second image is the study I did of the other units in my building. My apartment is the dark red trace. The bottom green trace is the power to the outdoor lights, which is on its own meter. The other traces are the other seven apartments. You can easily see the effects of the winter heating season. Sometimes the other apartments were vacant, and energy use was near zero, as in the case of the orange trace in June 2008.

Turning down the temp on the water heater to 110 deg F is TERRIBLE. You can’t even wash dishes with that – I’m talking washing by hand. The water is tepid at that temperature. Plastic bowls are almost impossible to get completely oil free as it is. You might as well just turn the hot water off. Possibly preheat with a solar panel? I would seriously consider this.

Did you think of putting a timer on the water heater?

The biggest thing I did was insulate the hot water lines. This made a substantial difference in hot water usage.

I’m in an apartment so I can’t put the water heater on a timer or tear open the walls to insulate the pipes.

110 F is fine for me (hot tubs are 104 F) and we don’t have problems with washing dishes. But, you still may be able to find a happy medium that gives you hot enough water but isn’t excessive. The default 140 F setting is excessive and dangerous.

In Australia all new domestic water services must be temperature limited to 50C (122C) into the bathrooms and (I think) the kitchen. In practice the plumbers just put the limiter on the main line so all the hot water entering the house is 50C. Hot water storage tanks, however are set to a minimum of 60C (140F) to ensure any nasties in the water are killed.

There is continuing debate about the need for this as the all the mains water is clean and chlorinated and dropping the temperature in storage tanks would improved energy efficiciency.

There are quite a few people with Solar Hot Water Units who simply turn off the boosters (esp. during summer) until they run out of hot water. Many rarely turn them back on even in winter.

I remember a few years ago there was a major distaster which disrupted gas supplies for three weeks in Melbourne which meant that the majority of households had no hot water. While all my neighours were scrambling around trying to shower at work or sporting clubs or friends houses, our SHW (with gas boost) never ran out of hot water. I was a smug little bugger at the time (grin).

We’ve been on Solar Water Heating for about seven years. We NEVER boost. Occasionally, after maybe seven days of cloudy/rainy weather, our water too goes tepid, still warm enough to shower, but as you point out not hot enough to wash dishes. But why on Earth would we want to boost an entire 250L hot water tank just to wah dishes when for a fraction of the energy cost we can boil just enough water on the gas stove to do the job?

Soon enough, the sun comes back, and by mid day our tank’s full of boiling hot water again….

Tom,

Wow, I am really impressed. I seem to chase my family around the house and turn off lights all day. I think I need to figure out how to start killing the phantom users in my house as well as striving to instill the “cherish energy” attitude in my home.

Also a note on power meters — I have a “smart meter” which does show the instantaneous power! It is nice, but it has a quirk — it shows the voltage for 5 seconds (useless, always about 240V), then it shows the energy usage for 5 seconds since I dont know when (basically some cumulative that isnt that useful, I can see that in my bill or online), then it shows the instantaneous power. I can always tell when the dryer is on! We use a ton of energy on laundry with two little kids always spilling, crawling, digging, puking, pooping, etc. I would hate to try and line dry all of it, I would need a bigger staff at my house!

Based on your post, I am inspired to really attack the phantoms and see if I can get my house down to what my utility bill shows as “normal house.” I know –awful, I think we may be 2x normal now. I am really sad that we (humanity) will use/squander our fossil inheritance in a mere 100 years. The century that burned all the oil… yikes. I want to be “less” a part of that.

Thanks again for your insightful blog! Maybe you should write down a policy strategy too that would be political suicide, but at least it would be written down…

Cyrus

I have long held (since the 1970’s) that the best policy is the Carbon Tax. Not that the Carbon Tax is all that is needed, but that it is an imprescindible first step. With a carbon tax which starts out small and then grows at a set rate over time, with the tax revenue returned to the people on a count-the-noses basis, people would know that the tax would be rising as inexorably as the tidewaters approaching King Canute’s beachside throne… except that the tax would not subside just as predictably as the ebbing tide.

http://www.carbontax.org

provides a wealth of information on the subject.

With such a tax in place, there would be blogs, magazine articles, how-to-do-it books and so forth galore. And people could readily afford the investments, what with the tax refund checks showing up as regularly as employed workers’ paychecks.

But much must be done to advance this dream from wishful/magical thinking into a movement and into reality. Prof Murphy’s essays and data show that massive home energy savings can be made, while life not only goes on but is entirely enjoyable. Behold! The 8@$+@^&$ are not freezing in the dark!

I am less driven to conserve than I am to hold down the annoyance factor. There are areas of the house I use only incandescent such as in the living room and den. Areas I use mainly halogen are the kitchen and laundry room. Areas where I use CFL are the outside porch lights. Install electric eyes (or motion detectors) in the porch light fixtures to turn on/off at appropriate times. I threw out 100 watt bulbs 20 years ago since their lifetime was annoyingly short. 60 watt incan and strategically placed reading lamps are best.

I find it it better to OPTIMIZE rather than MINIMIZE. That way there is a reasonable trade-off between a)cost b) convenience c) standard of living – usually by optimizing there is NO loss of standard of living.

The first paragraph explains the optimization. When kids are thrown in, then you must further optimize. Such as motion detectors in closet lights and bathrooms. One time I put in a sound activated light in my son’s bedroom. Kids just don’t grasp the concept of turning out the lights when they leave a room – until they are adults and they then have to pay for the electricity.

Want to really minimize electric usage? Just snap off the main breaker to the house.

Hi Tom,

Here in Huntington Beach in a 1500 sq ft single family home just up the coast from you. I have been averaging 5.74 KW per day for the last 90 days. That’s about a 20 % improvement over last year. Most of that comes from better management of the washer, dryer & dishwasher. My 650 Sub-Zero is an energy hog at 2 KW hours per day. Everything else in the home is all energy star except the old original furnace. It pulls less than .3 KW’s and consumed 22KW hours from the end of November to the end of February.

You should do a piece on “Coasting to Sustainability”. For years I have been getting 17 city and 25.5 highway flowing with traffic. By changing my habits I have improved that to 21 city and 32 highway with the same vehicle. The highway was easy done by simply slowing from 70mph to 55mph. The city is much harder to improve. It’s a matter of slowing down and learning the light patterns of my regular commutes. Then by timing the lights I use a lot more coasting before signals plus stop signs, turns and in residental areas.

That’s almost a 25% improvement in fuel economy.

I do hope that first figure is 5.74 kWh per day, and not averaging 5.74 kW of power draw!

Anyone out there still confused about the difference between kW and kWh may benefit from the useful energy relations page, describing the difference between power and energy.

You got me Tom, It is kWh per day. I bought my little Kill-A-Watt meter a couple of years ago and been killing those little Phantom bugs ever since.

I am officially impressed! 200W for a 2 person household is pretty amazing. My electricity bill says I use about the same, but I’m a single apartment dweller in Europe, who actually likes the dark.

200W avg. is darn low.

I’ve rewired our microwave so that it doesn’t come on unless you close the door and rejigged the door bell to use old 9V batteries. I should label different parts of this as they’re all clear – when I had a boarder in the home, when I got married, when the kids were born, when inlaws visit, when I replaced the 40 gal gas water heater with a 19 gal. electric, when we upgraded to a high-eff furnace.

We use a clothes line now, but even with 2 kids average about 1.5 laundry loads a week. Things were a bit insane with both in cloth diapers (that was 1 laundry load/wk) – but even that went on the clothes line in the summer.

During the summer we average around 225W, but the furnace slams us up to 400W in the peak of winter.

One summer we did turn off the water heater and used a black plastic camping shower bag to generate all of the hot water we needed. It’s just that spend $80/yr heating water doesn’t make it viable to go with SDHW.

Like others have commented here – our lifestyle allows us to get by with 1/2 of the water, electricity and natural gas use of our neighbours – around 1/4 that of the national average.

Really want to be impressed? We use less than 100W! http://damnthematrix.wordpress.com/2011/09/04/the-power-of-energy-efficiency/

and

http://damnthematrix.wordpress.com/2011/12/15/the-power-of-energy-efficiency-revisited/

More modern appliances have become amazingly efficient….. I just bought a DVD player (yes, slowly joining the technology revolution). My Killawatt meter tells me that it consumes 6W to play a DVD, and only 1/3 W on standby….

I can’t be bothered turning it off at that rate… 2.6kWh/yr is something I can wear on my sleeve!

I’ve been hanging laundry for more than 30 years. I never cared for it much as a kid when it was an assigned chore but now as an adult I find it mildly enjoyable. I certainly never tire of how well it works and how much it saves. Simple pleasures.

MANY thanks for digitally simulated disk info.

I’m just in from a quick check: 30 seconds / disk = 120 W load without the refrigerator running, but with the laptop on. This calculates out to about half the normal day load!

To do:

Furnace transformer cutoff

Doorbell transformer replacement

Power strip for the DVD/VHS

Maybe disable the garage door opener in some way too…

Well said, sir. For most households, I would argue that you’re probably underestimating the savings achievable from more efficient lighting choices. Most households have some usage in the higher tier rates, which can be as high as 20-30 cents/kwh.

Here in Sacramento, the utility subsidizes both high quality CFLs and LED lighting, and our household has taken advantage. We’ve gradually replaced 2000 watts of incandescent/halogen with 370 watts of LED in our house, and have seen our electric bill drop by almost $25/month! With the subsidy, our replacement cost was only $800, which we’ll make back in less than two and a half years. (Not as fast as CFLs, but we like the quality of the LED light better.) I’m proud to say that our 12 month running average usage has dropped from 26.9 kwh/day to 23.8 kwh/day.

I have heard that the lifetime of CFL’s is also dependent on how many on/off cycles they go through, not just total hours. This would seem to reflect my own observations, and that when you turn on a fluorescent bulb it takes a good minute for the thing to warm up to full spectrum / intensity. Flicking them on and off every time you walk down a hallway might not be best suited for CFL. I wonder if LED’s have this issue.

If this is significant then there must be some optimal hours-versus-cycles ratio that each person would have to figure out for each location in their house.

Apparently here in BC there are some original Edison incandescent bulbs in the hydro dams that have been going constantly for 100 years. No one wants to turn them off because they might blow the next time they’re turned on. They are part of our history!

LEDs, as LEDs (ignoring the power supply) do not have this problem. One way their light level is controlled is to simply chop them on/off at a high rate, and I know of some bicycle lights a friend has built where the AC output of a “dynamo” hub is fed through a pair of reversed LEDs — they are pulsed 10000 times in the course of a mile’s travel.

LEDs (as LEDs, again) are instant-on, and are most efficient at low temperatures. Some power supplies delay a moment or two before energizing, some do not. The spectrum of an LED will generally (note weasel word) be “better” than the spectrum of a CFL.

Gory specturm details here: (science)

http://dr2chase.wordpress.com/2008/05/08/spectrum-led-vs-fluorescent/

and here: (subjective, diff LED color temperatures)

http://dr2chase.wordpress.com/2011/02/26/led-color-rendering/

There are some cheap, exceptionally bone-headed ways of making a “white” LED from blue and yellow, that look like crap. I haven’t seen one of those lately, but beware.

The power supply itself is a concern, but we’ve gotten very good at building switching power supplies (every computer out there has one, so does every cell phone charger).

LEDs, as LEDs, are extremely durable; I have several bare power LEDs on bicycles that are always outdoors in Massachusetts weather, plus they are exposed to all the vibration that you get from being attached to a bicycle. Imagine lashing a CFL to a bicycle and riding it a few thousand miles on potholed Boston metro roads.

Leds “will” be much better. No flicker, no warm up period (my CFL’s are always dim at first because we live in the mountains in a less than comfy room temp), no mercury, and leds “will” have better quality light.

They are pulsed hundreds or thousands of times every second when driven by certain led drivers which are electronics that maintain a desired constant current (thus no worry about constant switching on and off).

The Cree XML is rated at over 100 lumens per watt for warm white (for just one watt, higher power will reduce efficiency slightly) and 160 lm/w for “cold” white! Unfortunately, not already mass produced for normal sockets yet.

Just one can light a room using less than ten watts (3.3v and 3A is their rated max)… And should last 100,000 hours (that is slowly fade to about 70 to 80%) within proper electrical and thermal constraints.

I have one connected to a single li-ion battery (in a 3.7v flashlight) that I charge with a cheap 6v solar panel… It lights up the entire room when directed towards a piece of paper taped to the beams…

Before going too far down the lighting road, let me announce that I will be putting together a lighting efficiency/spectral extravaganza post in the near future. I’ll likely deflect further comments that will be best suited to that post (stay tuned…).

There are a lot of myths, exaggerations and outdated information associated with CFL’s. Many of the problems like dim starts and poor colour rendition have been solved by all but the cheapest globes.

The issue with on/off is completely overblown. All lights have this issue (although in LED’s it is insignificant) but even if the lights are cycled many times a day it will not make much practical difference. If the lifetime drops by 10% (or even 30%) you are still miles in front compared to the old incandescents.

Not true that Europeans don’t use dryers. Faced with the choice “dryer or divorce”, I found not only a model with heat pump which uses about half as much energy as conventional dryers. I also found out that the regional government of Brussels supports the purchase of such an “energy efficent” dryer with a subsidy of up to 50% of the invoice.

Yeah, when I traveled northern Europe, I saw washer/dryer units everywhere I stayed. Mind you, many of them didn’t seem to work very well.

Not using dryers in northern Italy, or Madrid, puts us back to how easy it is to have a small energy footprint when one lives in a very nice climate.

Glaeser suggests that it would be greener to build high-rises along the California coast, where the climate is nice, than to exile them to the central valley or to Houston sprawl, where people will be running A/C a lot more.

A warm climate is actually not really a requirement for choosing line drying of cloth. A good combination of air flow (wind) and air humidity is what matters. Line drying even works at freezing temperatures, although it may take bit more time for water to evaporate.

We have one set of lines on the lawn, and one set under a roof (combined bicycle shed), but the generally elevated humidity during rain increases the time for drying significantly irrespective of the temperature.

Unfortunately, many municipalities or HOA have by-laws against clotheslines (even the standalone tree models) because they “look unsightly”. Municipal zoning has a significant effect on energy/resource consumption. For example a higher density will result in lower resource/energy compensation than the standard suburban/rural-suburban model in the United States.

Obviously “it depends” (on the country, location, income level, …) but I lived in Scotland for years, and pretty much nobody who’s apartment I saw had an electric clothes dryer—student, young professional, old fogie, you name it.

They do have a secret weapon though: ceilings are often very high there, and what everybody there does have is a clothes drying rack attached to the ceiling, and lowered by a pulley system. This system works extremely well: even indoors, with the typically damp and cold Scottish weather and often fairly anemic heating, stuff dries very fast. Apparently there’s a lot of hot air that accumulates near a high ceiling…

[I now live in Japan, where most people “line dry” (not actually on a line, but on metal poles) clothes on their balcony, although clothes dryers are slowly gaining popularity. Most Japanese clothes-dryers are insanely low-powered, and take hours and hours to actually dry anything anyway…]

One thing I’ve noticed is that not having a dryer, and only using cold water for washing (my washer doesn’t even have the ability to use hot water) makes buying clothes much more convenient: no longer do you have to guestimate what size you should buy and live in fear of excess shrinkage… whatever fits in the store usually still fits after washing many times…

Of course, urban areas also have laundromats; I used one in Glasgow. (And the machines were happily familiar and effective, unlike all the others I saw in Europe.) And in the US I’ve never had a rental apartment with its own washer even, though I’ve seen one; they’re usually in the basement and coin operated (along with the dryer.)

Thanks for this excellent post. I had never figured out the trick with the digital electric meters (mine has a single flashing triangle that registers 1 Wh), but now know that I am burning a continuous 70W to do absolutely nothing.

Your point about lifestyle is right on mark – my wife and I consume only about 250 kWH/mo, without doing anything remarkable at all. Fortunately (or unfortunately) power in the Pac. NW is so cheap (~$0.05/kWh) that it is very difficult to economically justify reducing consumption.

I had my wife read this blog entry just so that she would appreciate that she is not married to the biggest energy kook on the planet. You must be married to a very understanding woman.

How much less electricity does your fridge use since you are keeping your house cooler, by not heating it?

Great question. I see seasonal variation. As low as 25 W average (0.6 kWh/day) during the colder periods, and around 50 W (1.2 kWh/day) in the warm summer. The average over the year is about 38 W. Two things are going on here: the refrigerator does not need to work as hard to maintain a smaller temperature difference, but also, the thermodynamic efficiency of a heat pump increases as the delta-T gets smaller.

My 21 year old fridge averaged 36.6 W over the last two days. (1.83 kWh used over 50hr) I don’t think I will go out of my way to replace it with a new unit as this seems like pretty decent performance. I’ll have to run the numbers again in July

Dear Tom,

Love the ideas, but I have a cautionary parable. A man built a passive solar home heated by wood stoves that was nearly self sufficient in land and energy. In his zeal, he eliminated even a garbage disposer in the sink, so his wife would always compost the extensive garden he wanted her to cultivate with hand tools. He kept his power tools, of course, for cutting wood, building and crafting. His wife became weary of living a 19th century life, and divorced him. The wonderful house had to be sold at a rock-bottom price long before its energy features became critical, and now he has nothing to show for his work. I know this story because I now own this incredible house.

This leads me to two simple rules:

1) Let the least enthusiastic partner be the final decision maker.

2) Never sell someone else’s energy slaves before your own.

Is is too un-PC to note that of a partnership containing the 2 best-known genders, the male of the species usually seems to be the more enthusiastic watt-killer? I don’t know what to make of that, except that C Breeze has the right approach.

We have fluorescents in all our most-used lamps. My wife has occasionally groused about the color, but I’m not sure I can even tell the difference, and certainly don’t care. We both read constantly.

In southern Wisconsin, there’s a lot more temptation for both heating and cooling than in SD, of course. Neither one of us is inclined to use AC, or overuse heat, so that’s an area of agreement. For exmaple, we never use the furnace while sleeping, even if <0F, in a 60's house without special insulation. But I will push it further when given a chance. Because of the freak heat wave, we haven't had the furnace on since early March. Since she's currently out of town, I get to extend that streak even if indoor temps drop to 50F. With the weather we're getting lately, it will soon be back to 70.

Anecdotal evidence is that women tend to be more sensitive to the cold and more sensitive to color.

Anecdotal counter-evidence. My son’s mother-in-law, in her late 70’s, is on an extended visit from China. On a previous visit she nagged about the house being too hot in the winter, warning that it was making everybody (herself included) sick. This past winter the house has been in the upper 50’s. She has been happy, the whole family has been cold-and-flu free. During a visit, my wife (early 70’s) was about ready to check into a hotel until the kids pleaded; she took to wearing multiple sets of long underwear, etc. And she did not get sick. We now keep our Chicago home in the low 60’s and are healthier this winter than last.

My son’s mother-in-law is from northern Hebei Province; my wife is from Central America, of tropical American & African aboriginal extraction. I doubt if genetics or gender has much to do with the matter, based on my anecdotal experience.

I slept in an unheated basement when in grad school. Many thought I’d die of pneumonia, but it was the best cold and flu season I’ve ever had. The warm super dry air from central heating is a killer.

I love your blog. I take the energy ‘thing’ seriously, and in fact am nearly finished with a homebuilt solar hot water system. Having said that, I have just completed an audit of most of the potential vampires in my house and surprisingly don’t see much room for improvement from managing these. I looked at things like multiple wireless routers, the cable modem, entertainment electronics, printer, microwave, etc. If I turned all of them off for 22 hours a day, I would save 630 kwh in a year, a savings of $60, about 3.3% of my total usage. I’ am going to take steps to manage these, for the reasons you mention, but I’m quite surprised at the relatively minor savings. It doesn’t seem to live up to the hype.

It is a smaller percent savings for you because you are using alot of power otherwise, look elsewhere for what is using all your power.

Regarding clothes dryers and your comparison between US and Europe, this reminds me of an incident when I was in grammar school in the 90s. Two of my classmates were planning to go to the US for a year as part of a student exchange, and in preparation they received a booklet by the Ministry of Education about their country of choice.

In this booklet, which mostly contained general information about the United States (history, culture, traditions etc.), they stumbled upon a curious paragraph. When they read it, they first looked at each other in disbelief and then started to roar with laughter. They showed the paragraph to the other students and the whole class joined them in their incredulous laughter.

The paragraph went like this:

“In the United States, you are expected to change your clothes every day. For example, if you wear the same trousers or sweater to school you were wearing the day before, people might ask you if you somehow didn’t make it home and had to stay at a hotel during the night, because otherwise you would surely have changed your clothes. It is a cultural thing.”

For us Central Europeans teenagers, who wore our jeans and sweaters for a week or more (never throw something into the laundry if it doesn’t smell bad or is outright dirty!), this seemed so strange and outlandish we genuinely believed it to be a joke. Apparently, it was not – at least that’s what our classmates told us when they returned a year later, though it still seemed unbelievable to us.

Great story. Unless people are being overly-polite, my repeated-use policy is not causing anyone consternation (though I rotate through the stack so a few weeks might go by between wearings, and half-a-year or more between washings). The jeans, however, go days and days in a row…

Rotating through a stack is a very useful approach; I do that as well nowadays, at least for shirts and t-shirts. Interestingly, when I was a teenager, this practise was generally viewed as something only girls did (because girls, of course, were vain and wanted to dress differently from day to day).

I guess these habits also have a socio-economic background. I grew up in a small town/rural area where the general attitude was not to waste anything and to live thriftily, so even if people could in principle afford to waste electricity by using clothes dryers and buy heaps of consumer goods (Austria has been a wealthy country since the 1960s Wirtschaftswunder), it was mostly frowned upon, especially by older people. My impression is that this was less so in the urbanized areas around bigger cities.

Congratulations! Now to the money-and-energy-and-water savings of reduced laundering, you can add more savings in longer-lasting clothes. Notice all the lint in the clothes dryer filter? That comes from fabrics that were grown on a farm or a fossil «fuel» processing establishment. What determines the number of «wears» you get from (let’s say) a shirt is how many times it is washed; the number of times it is worn is not quite but almost irrelevant. (I don’t have numbers or references. My apologies.)

I have experimented on repeat wearings and giving clothes a few days rest. They truly do get more wearings between launderings, generally over 50% more. (This also applies to jeans!) Tip: Hang them in the open, like on a hook on the closet door and NOT in the closet! And note to C Breeze: My wife is insistent on laundering, to an extreme, so I do not practice what I preach as much as I would. And we are still married.

Maybe I should contribute this under a pseudonym, but …

Jeans getting citified uses like casual Friday at work, knocking around town for errands, etc, don’t need washing. If it’s warm enough you would sweat heavily into them, then wear shorts, duh.

For turning your compost and the like around the yard, wear your older jeans. You won’t wear those anywhere you need to look natty and smell nice, anyway.

I live in a house where we are very careful with energy use and found we were using alot of power all of a sudden last summer, so I decided to do some detective work and find out what the culprit was. I did this by looking at the meter and shutting of all of the curcuit breakers, then putting one at a time back on — The high power user was the wellpump, I had to investigate further to find out what was going on, but it basically was running constantly on, 24 hours a day, which not only uses alot of power but will burn out an expensive pump, so I am glad to have found out I had this problem — pumps are supposed to shut off when they arent drawing any water !

Great write up! Thanks for taking the time.

For those looking for a less espensive version of TED, you might look into the Black & Decker EM100B Energy Saver Series Power Monitor. I got mine from Amazon for less than $40. Similar idea as TED – has an external sensor which you attach to your analog (wheel) or digital power meter, and it radios the info to a base inside the house. No PC/internet connectivity, but much cheaper.

Also, for those of us who have electric hot water heaters, a heat-pump hot water heater is a great option. It’s a drop-in replacement for an electric hot water heater (ie, simpler/cheaper to install than solar) and has saved me about 300kwh/month since I installed mine last year. Or, if you happen to be replacing your HVAC system, check if the manufacturer has a hot water kit – you’ll get similar or better results than a stand-alone heat pump hot water heater.

Thanks again!

The Japanese don’t use clothes dryers. In fact, I have to explain to them what a clothes dryer is.

Starting ten years ago I saved by eliminating the 10 minute shower, rigorously getting it down to 3 minutes and that not every day either. I never, save for once or twice a year, take a full bath anymore. I now sponge bathe several times a week, thereby using only a couple of quarts of hot water. Only a coal miner needs more time in the shower. I recycled some of the shower water by catching it into a basin and washed my socks and underwear in it. Savings? 40% on utilities. I was living in a 650 sq ft apartment (in Europe, mind, so adjust some) and saved ca. $800 (ca. €500 at then at ca 1.55 per €) per year. Heating and lighting I watched more carefully as well. Heat and light I consumed less as well. These are not exact figures save for the 40% on the next (and successive) year’s adjusted bill. I was stunned! Technical and political solutions won’t save me that $800 soon. You do it.

I am amazed at how many people have major electric appliances, where here in Chicago they are Nat Gas appliances. My Furnace, Hot Water, Range/Oven, Clothes Dyer are all gas driven. AC, fridge, dishwasher, clothes washer are electric.

Personally not a huge fan of AC, except on the most humid days in august. Dishes every 4 days. About 5 loads a week.

700 sqft condo, single person, works from home. Averaged 285 kWh in 2011.

Funny thing, since I graphed my data, I see a peak in Aug like expected for AC. There is also a rise to Jan/Feb. Mean my track lighting is costing me waaayyy too much. Those darn 50W halogen bulbs (x4) need to get replaced.

I’d be curious to see these numbers put into some context in terms of other energy consumption habits. Perhaps by dollarizing the savings, or gallons of oil BTU equivalent, or something.

The way the math usually works out here is that you jump through 300 hoops to save energy around the house, and then you take one vacation in Maui and blow away 3 years worth of savings.

Not to be mean, you’re having fun with this stuff. And for all I know, you don’t go to someplace tropical for fun. (All my environmentaly minded friends do… ) But I think the vacations in Maui/Costa-Rica are the bigger blows to your annual energy profile that wearing shorts in the winter in your well insulated condo.

No doubt you need to look at the big picture, and recognize how easy it is to blow the other efforts. Then again, such thoughts prevent some cynics from even trying. And that’s not very nice either, is it?

“Then again, such thoughts prevent some cynics from even trying.”

Well, the engineering approach is to study the breakdown first and then cut appropriately. I.e. if heating and AC are 20% of your energy consumption and leisure travel is 50%, cutting the former to Spartan levels while leaving the latter unadulterated doesn’t make much sense, particularly if you’d be happier cutting your leisure travel in half and maintaining temperate personal quarters in your own home.

You could also see how this sort of hypocrisy would keep the “energy reduction personal ethic” from getting off the ground. When the Al Gore types travel with such frequency, it does sort of dull the enthusiasm for sleeping on top of a bed heater and wearing three sweaters.

I agree. The idiom “every little bit helps” is one that I hear constantly in the energy conservation movement and as an engineer I take it as my queue for a brief lecture in opportunity cost. It’s just as correct to say that “every little bit costs” since resources (time and money) spent seeking reductions in one area are resources that cannot be spent seeking reductions in another. If maximum reduction is the ultimate goal, and assuming limited resources to invest towards that goal, it’s important to determine where the greatest reduction can be found for the least investment and start there. By the same token, it’s also important to DO SOMETHING since doing nothing will (usually) have an even greater opportunity cost.

Tom, I’m in no way suggesting you haven’t chosen wisely where to focus your efforts. I expect that opportunty cost has factored largely into your choices. Just making a point.

Our energy profiles are very diverse. Any serious effort to reduce must happen on many fronts. I only describe one at a time in these posts, leaving myself open to charges that such actions in isolation do not amount to much—possibly discouraging people from even trying. But overall, I have made something like a factor-of two impact on my total energy consumption through efforts at home, reduced travel, diet choices, consumer practices, etc. Meanwhile, there is something to be said for plucking the easy low-hanging fruit, even if trivial in itself. Just do it. Net gain. Little loss. What’s to argue? But far better if you don’t stop there.

That reminds me of an interview with David Suzuki (I think) who, when asked, “Is it better to buy milk in plastic, waxed paper or glass containers?” responded,

“I think it would be better to walk to the shop instead of driving and buy the one that suits you better!”

It drives home the point that sometimes we can get lost in the detail and lose sight of the bigger picture. Of course, the big picture without the detail can also be inadequate and misleading.

It’s one thing to assess your personal energy breakdown first and cut appropriately. It’s quite another to quit trying just because *someone else* is using far more energy. Seems to me we should all start with what we can personally control, and try to set an example for others.

I think you could separate essential from non-essential energy use and surprise yourself. You don’t have to suffer a “19th century lifestyle” to reduce your usage and save some money. Case in point: inspired by ya’ll, I’m beginning the hunt for vampire energy usage. Just discovered my Dell 3010cn printer consumes 30 watts in “sleep” mode. That 0.72kwh/day was 3% of our electrical consumption last year, and cost us $35! We use this printer maybe once a week.

Believe me, my family wouldn’t tolerate a 50F house in winter. But they won’t even notice that the printer is off.

The key point here is that, ultimately, you can’t control what you don’t measure. I always remind people when I am advising them about energy efficiency around the home that it’s about making informed decisions. For example, if you have a great view that faces the wrong direction (away from the equator) then you have a number of options; retain the view and wear the energy cost, remove the view (heavy curtains, smaller windows, etc.), improve the window performance (double/triple glazing etc.) or compansate in other areas. At least you know up-front what “cost” is, rather than saying six months done the track, “oh, if only I knew about that, I would have….”.

At the end of the day you want to enjoy living in a house that happens to be energy efficient, not have to live in an energy efficient house that you hate. The same is true for the rest of your lifestyle.

Rather than thinking that you have blown all your energy savings by taking that holiday, why not look at it as using those energy savings to pay for your holiday.

Because it’s half the calories, you can have twice as much! You’ll never lose weight that way. Controlling energy expenditure is a worthy task, as long as it results in a net reduction. I would hope that people do not take more energy-intensive trips than they otherwise would on account of savings elsewhere. Then there is no net progress.

Here’s a little graphic I produced a few years ago that illustrated the cost of using incandescents vs CFL’s back when CFL’s cost $15 and our electricity was $0.15/kWh. I have added an updated chart using our current rates of $0.23/kwh and (quality) CFL prices of $7. Our rates are set to rise again soon which will push the difference even higher.

http://imgur.com/a/qE5cY

Led lights are now competing effectively with CFL’s and will continue to get cheaper.

A really interesting point to note was that even if they were giving away incandescent globes for free, it would still be cheaper to spend $15 on a CFL (or $60 on LED lighting)!!

I love the charts, but they seem to consider only the cost of lighting and not the total cost of lighting and heating. When total cost is considered, CFLs and LEDs still shine (pun intended) but not quite as brightly. In particular, for a home heated with electricity, the choice of lighting will have little effect on energy use during the heating season since a certain number of Watts is required (light or heat… it doesn’t matter) per degree of your thermostat setting (about 200W/degreeC for my home). From a purely cost perspective (ignoring the value of your own time) if you heat with electricity you will probably find the optimum choice is to light/heat with incandescents during the heating season, and save your more expensive CFL/LED bulbs for the rest of the year when they will actually have an effect on total energy use. You will thus extend the useful lifespan of your CFL/LED bulbs.

In a location where the heating season is half the year, adopting such a strategy vs simply using CFLs year round should save on the order of $5 per CFL bulb over the bulb’s new lifespan, assuming the price of CFLs doesn’t change in that time.

It is a minor point, but it highlights the need to look at total energy use of a system rather than that of any isolated component. If you don’t heat with electricity, or if you value your own time, install CFL/LED bulbs and forget them, but recognise that while you’re decreasing your lighting costs, you ARE also increasing your heating costs. Depending on the heating requirements of your home, the net benefit may not be as much as it appears at first glance.

Good points. However, pushing the analysis further, if you consider using a heat pump (eg reverse cycle A/C) with a COP above 1, then the total electricity cost will be less when using CFL’s. If you are heating with electriciy you should seriously consider this approach anyway.

Of course a simpler solution would be to use the cost savings to install additional insulation, or window treatments, or even a really snuggly jumper!

Sorry, but CFL’s are garbage- all of them. I have a mix of incandescent and halogen bulbs in my apartment and anything else is beyond ugly. I’m an artist and photographer and the quality ad color temperature of the light in my home means a lot. I’ll do without AC before I submit myself to the cold, ugly illumination of CFL’s. Spare me the analysis of energy savings and cost/benefit- the light that they produce is ugly and makes my world ugly and there’s no price tag on that.

Telling me that CFL’s are just as good as incandescents because they generate the same amount of illumination for a fraction of the cost is a pointless argument. It’s akin to telling me to forget about steak or Mahi-Mahi because boiled beans have the same nutritional value. You can choose that diet for yourself but if you try to force it down my throat you’ll have a fight on your hands!

There’s no forcing going on here. Great if you can accept the compromises, but not everyone will. And believe it or not, some people do forgo steak and Mahi-Mahi for energy reasons. No one universal set of priorities.

Totally agree about the color rendition of Halogen globes, and I always advise people who need good quality, bright, color neutral task lighting, that halogens are currently the best choice.

However, things change, and the performance of CFL and LED globes, including color balance and color rendition is improving. Keep an eye on the market, you may be pleasantly surprised one day to find an energy saving globe that meets your exacting standards.

I decided a long time ago to start taking the stairs at work because it seemed to me a rediculous waste of energy to lift the entire weight of an elevator five stories just to lift my 200 lbs the same distance.

When questioned by my colleagues as to why I was taking the stairs, I found that:

If I said “for the exercise” I would generally get responses of “good for you” or “good idea”.

If I said “to save energy” I would generally get groans and eye-rolling in response.

If taking the stairs or using CFLs are actions that are benign in terms of their direct impact on other people, why are other people so sensitive to the motive behind such actions?

[substantially shortened by moderator]

Like Tom and many of his other readers, I am serious about energy conservation and environmental issues in general, and I too have cut my personal energy usage drastically, but I also think a key point is that every situation is different, and I have some advantages that many do not.

[details removed]

My lifestyle is basically a lot like that of a student living in a dorm room, in that I have my bed, my desk, my computer, my Internet connection, and a microwave in this one small room, so it is cozy, but not cramped for one person, or otherwise uncomfortable.

[more details]

In short, I pretty much have the energy demands of someone living in the third world, yet I have most of the first world comforts, such as clean water, comfortable living quarters, good sanitation, modern telecommunications, etc.

I also buy very little in the way of consumer goods. Indeed, aside from food and clothing, I buy almost nothing of any consequence, since most of my entertainment comes from the library and the Internet, and I also travel very little, at least at present.

[more details]

In short, I have two major points.

First, anyone can make dramatic cuts in their resource usage, and still maintain a very comfortable, modern lifestyle. This will also reduce your cash requirements equally drastically, which in turn will make it very easy to achieve a real level of economic security.

Second, while there are any number of things one can do along these lines, the particular combination that works best is unique to each case.

That is to say, you will only stick to such a regime if it really suits your temperament and lifestyle, so you must pick those tactics that help you achieve your overall goals in life, and relax a bit on those that don’t.

However, do consider all the possibilities. You never know when something will fit in better than you first thought, or when one idea that does not fit will inspire a related idea that does.

As Voltaire said, don’t let the perfect be the enemy of the good. It’s fun and useful to obsess a bit about this stuff, but don’t let it wreck your peace of mind.

Actually, come to think of it, sailboats are still perfectly good ways to cross oceans, and especially so for those of us with no jobs to worry about. Lots of fun, too.

I’ll have to think more about just how to finagle such a thing, but, for example, there are companies that deliver yachts to rich, overseas customers. There are also lots of boat owners with hired crews for longer trips.

These days any idiot can navigate with GPS, but it happens that I also know how to do it the old-fashioned way with a compass and sextant. That would be handy if the batteries in the GPS died.

Again, the general point is that every situation has trade-offs, and in my case I have both time and serious sailing skills. You may have another set of advantages that would let you solve the problem some other way.

I don’t mind that the moderator trimmed my original comments by cutting out the how-to details of what I do to live conservatively, however, he did leave my follow-on comment looking like a complete non-sequitur.

The reason that I added the after-thought about sailing is that I had mentioned an interest in doing some travel, but didn’t want to use jet airliners to cross oceans. Then, later, it occurred to me that I might find a way to use a sailboat to get to other continents, given that I have to time to travel that slowly, and I have the relevant experience to do it safely in a boat.

My point again is that every case is different, and there is no universal approach to energy efficiency. However, if you play with these questions long enough, you may find some very cute solutions for your particular situation.

If you’re going to count the waste heat of incandescent lighting as a benefit during the heating season, you also need to account for the unnecessary load it puts on air-conditioning during the cooling season.

It irritates me that some “green buildings” I’ve visited have high-efficiency lighting, but only one switch to control the lights over a hundred desks. Those of use who prefer less lighting (to make it easier to view our LCD screens) are forced to physically remove the (fluorescent) lamps tubes, rather than simply pull a string to turn off the light. With LED fixtures, we probably won’t even be able to pull the light-bulbs out.

A couple of weeks ago, the Washington Post ran an article bemoaning the expense of the new $50, ten-year LED light bulb. They did a 10-year cost comparison, but implicitly used a cost of electricity of $0.01 per kWh! A few days later, the corrections column admitted the error, but who ever reads corrections? “The purpose of corrections in a newspaper is not to correct the record, but to imply that everything left uncorrected was in fact the truth.”

Found another “phantom”: Our house has 11 dimmers that have a small backlight to make it easier to find the switch in the dark. Strangely, neither the spec sheets for the dimmers or the manufacturer’s web site list the power consumed by the backlight, so I emailed the manufacturer directly. Turns out they each use 0.75 watts, so with 11 of these the annual total consumption is 73 kwh, at a cost of nearly $10. Luckily, there’s an internal switch to disable the lights. My quest continues…