People rarely recognize or admit that they have been brainwashed. Perhaps the term brainwashed is too extreme, in which case manipulated or fooled may be substituted.

An insightful quote from Mark Twain says:

It is easier to fool people than it is to convince them that they have been fooled.

What often happens, in fact, is that people on opposite sides of an issue suspect (or are convinced) that the other side has been brainwashed. Sometimes one side is more justified in the charge than the other, in which case the brainwashed victims effectively assert a sort of projected symmetry that rings false.

Bi-directional allegations of brainwashing show up in the context of COVID: masks provide a clear means of identifying either those (masked individuals) who have been fooled into controlled submission to believe that the pandemic is real and deadly vs. those (unmasked fighters for freedom) who have been sadly misled to think it’s all a hoax and in so doing endanger us all. Each side may feel anger or pity toward the other. Climate change is similar: its denial has become an article of faith for the brainwashed non-believers, who accuse the gullible believers of being brainwashed by self-serving scientists vying for funding, power, or something (cake, maybe?).

To either side, it seems inconceivable that someone could deny the truths that are so obvious to them. For me, an uptick in total deaths closely matching reports of COVID deaths is pretty convincing, and it is hard for me to make out why anyone in power would want to wreck the economy and could somehow convince countries around the world to overlook a competitive advantage and follow suit. It boggles the mind. Likewise, I can see how climate change threatens powerful interests like the fossil fuel industry and even perhaps capitalism writ large—via the imposition of unwelcome limits on what we can do. But I have a much harder time understanding the bizarre allegations of scientists rolling in dough by hopping on the climate change bandwagon. That’s not how it works, people.

In this post, I will provide an example of how I evaluate the question of whether I have been brainwashed in the case of climate change, contrasting the way my knowledge is “received” to that of the opposition.

Precipitating Event

This post was motivated by someone in the financial world noticing my textbook, thinking well of it, and writing a piece that began with an extended quote from Appendix D.6:

So here’s the thing. The first species smart enough to exploit fossil fuels will do so with reckless abandon. Evolution did not skip steps and create a wise being—despite the fact that the sapiens in our species name means wise (self-assigned flattery). A wise being would recognize early on the damage inherent in profligate use of fossil fuels and would have refrained from unfettered exploitation. Not only is climate change a problem, but building an entire civilization dependent on a finite energy resource and also enabling a widespread degradation of natural ecosystems seems like an amateur blunder.

The piece got picked up and published at Zero Hedge, where I made the mistake of scanning the comments. I was appalled, and depressed at the sampling of humanity that we hope will act rationally to avoid the worst fate. It gave me an instant appreciation for the high quality, thoughtful comments posted to Do the Math. Granted, I don’t agree with all commenters, and do reject the occasional vacuous or vitriolic entry. But the Zero Hedge comments were dominated by empty posturing. A common refrain followed the formula:

I stopped reading as soon as I saw climate change.

and

Who pays these people to keep writing this BS about climate change?

The former showed up so often that I took it as a learned reaction to signal one’s virtue as a denier: an expression and re-validation of tribal identity. The latter made me laugh, on the basis that my book is offered for free, and actually required me to pay for some permissions, ISBN numbers, etc. I also am abandoning a well-funded research career in astrophysics to do this more important work on planetary limits. In academia, by the way, how much grant funding I receive does not determine my salary, so the often-assumed personal gain incentive is not as direct as is imagined. In any case, I am walking away from any known or likely prospect of research funding. So there! I’ll bet that in the eyes of those who think I am grievously wrong, this choice just makes me the saddest sack: duped into believing a big lie and doing the exact opposite of profiting from it. Stupid, squared!

Ironically, climate change was not even the main point of the quoted message, as it seldom is for me. Yet it’s a third rail that made some readers’ eyes bug out, hair stand on end, ears vent steam, and brains shut out the possibility of absorbing anything else in the article.

My Programming on Climate Change

So let me unpack how I became brainwashed to believe that climate change is anthropogenic, and is responsible for rising global temperatures.

Climate change for me is not as much a matter of belief as it is personal investigation and scientific understanding. Like many or most scientists, I see myself as a skeptic, not a follower. Presumably my out-of-the-mainstream message that our entire system and set of values are pointing us toward self-inflicted ruin, or the fact that my primary astrophysics endeavor was to test whether General Relativity is really correct (it seems to be so far), should give credence to this assertion. As a social animal, it can be hard to adopt an isolating, minority view within a department focused on very different matters.

Is climate change a belief for me? I suppose everything in my head could be described at some (pointless?) philosophical level as a belief. I believe the earth is round. True, I have personally measured its radius myself in various validating ways. I believe that air is made of molecules, themselves composed of atoms, even though I have never seen an atom in my direct experience. I believe that light is carried by photons (okay, I have seen/measured individual photons in my lab, and sent them on round-trip journeys to the moon). Any time I have had an opportunity to check some “known” piece of physics/chemistry for myself, I have come out satisfied that the textbooks are not lying to me. I haven’t checked everything: I’m just one person. But myriad other scientists are just like me, and have checked the things I haven’t—over and over, around the world, for decades and even centuries. Believe me, if a scientist has an opportunity to effect the rewriting of standard textbook material, they’ll jump on it—such is the glory of changing a paradigm. Nobel prizes tend to go to those who have made such a revolutionary impact on knowledge and understanding. I think what I’m saying is that scientists—almost by definition—are better described as explorers than as sheep.

But let’s get to climate change, and why for me it’s not entirely “received wisdom” but checks out through my own independent explorations.

First, I am convinced that methane (natural gas) molecules are formed by one carbon and four hydrogen atoms. I cannot claim direct evidence, but understand the process by which such things are determined—having performed similar experiments in chemistry labs to elucidate ratios of atoms in compounds (it also makes sense in terms of shared electrons and number of bonds). Likewise, I trust that oil is composed of hydrocarbon chains: a backbone of carbon atoms and two hydrogen atoms for each carbon, plus one more at each end. If you’re not on board with me at this point, I can’t decide whether to admire your hairshirt-level scientific empiricism or to shake my head at a lost cause.

The next step is easy: once understanding the composition of fossil fuels, it is almost literally childs’ play to introduce diatomic oxygen molecules from air and then rearrange the “balls-on-sticks” models of the molecules into new arrangements that leave CO2 and H2O—carbon dioxide and water. Together with the masses of the constituents (I understand several angles of verifying this, from both chemistry and nuclear physics), it is straightforward to understand that the resulting carbon dioxide mass is roughly three times the mass of the hydrocarbon input—much of the mass coming from the oxygen molecules.

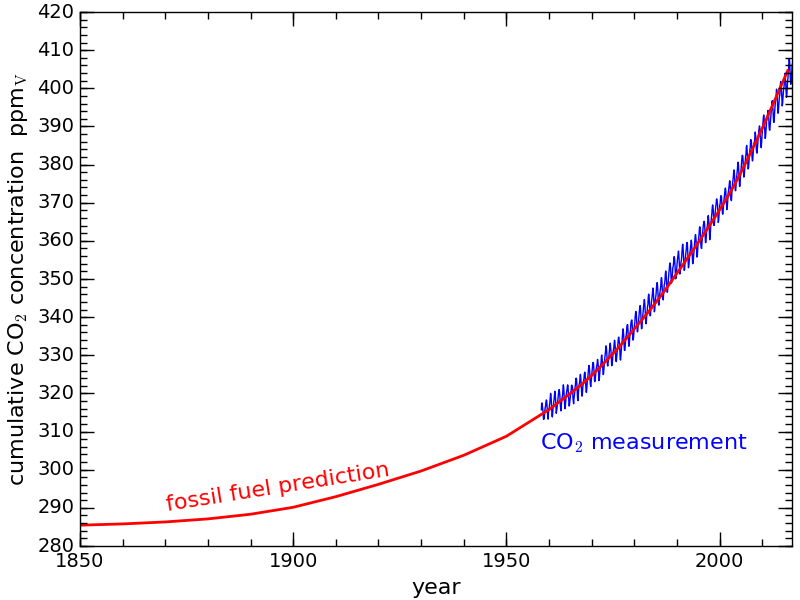

Many years back, I independently checked my understanding—as scientists are prone to do—of the observed CO2 build-up in the atmosphere by estimating how much I would expect it to rise per year based on reported knowledge of global annual fossil fuel consumption, and also the total post-industrial CO2 rise to date based on cumulative fossil fuel use (later conveyed in a Do the Math blog post). The result was actually twice as high as the observed rise, upon which I learned (or “discovered” for myself) that half of the emitted CO2 is absorbed by the ocean/ground. But even leaving this wrinkle aside, it was very powerful to realize that anthropogenic CO2 emission has no problem accounting for enough CO2 to explain the observed rise: we need not look elsewhere for the source.

I took this to a new level in preparing my textbook, deciding to produce a “prediction” graph of CO2 emission over time using as inputs only historical fossil fuel records and knowledge of the chemistry. I overlaid the prediction on the measured CO2 from Mauna Kea (the Keeling curve) to just see how well they agreed. The result, reproduced below, made my jaw drop. I mean, I knew it would be decent, having crudely verified annual increase and cumulative increase before. But seeing the entire shape line up gave me a mic-drop moment. I didn’t do anything to force it to be so good!

No one gave me this plot. I didn’t find it somewhere. I don’t recall ever having seen one like it. I was curious, and went exploring to see what I would find. I wrote the Python program from scratch that read and parsed the historical fossil fuel data file, performed the chemistry calculations, and generated the graph (see text for details). I feel like I own this result in a way that I never would if somebody just showed it to me. I know what went into it, and why I can trust it.

The final step is an understanding of heat transfer and radiative transport in the atmosphere—both of which I have enough personal context to comfortably assess and understand (believe?). Radiative heat transfer is dear to my heart, and I have made loads of personal measurements/confirmations of how this process works. I have thoroughly explored my world using a thermal-infrared camera, performing supporting calculations; dealt with cryogenics in which radiative heat transfer is an enemy that must be well understood/quantified; validated planetary surface temperatures based on this phenomenon; and obtained countless spectra of stars and galaxies that emit radiative power. No talking head can undo all that personal experience. Also, like all astronomers, my observations have been constrained by atmospheric transmission windows, and I know what happens when I try or hope to get infrared light through the atmosphere at absorbed wavelengths. Those absorption features are real and limit the wavelengths I could observe. It’s not just words in a textbook, for me, but direct experiences at observatories where I have (not) seen the blocked wavelengths with my own tools. Incidentally, my gold-standard reference for describing radiative transport in the atmosphere is by Pierrehumbert in a short article in Physics Today.

Given an understanding of how infrared radiation interacts with atmospheric constituents, I can perform calculations of expected heating from trapped solar input that reasonably match observations and climate science. It all becomes rather transparent and personally accessible.

Epistemology

I should be careful throwing around words I rarely use (physics does not often concern itself with lofty language), but I think this one fits: how we know what we know. I have given an account of my background understanding of climate change. It would be fascinating to get a comparably explicit account from one of the Zero Hedge deniers. I suspect many of them would not operate on that plane, and may not even see the value in such a challenge. But if someone did try to articulate their opposition, what themes would emerge?

Most would present second-hand wisdom: repeating what (select) others had said. Even though I am doing some of that as well (though less selective, concerning chemical composition of octane; historical fossil fuel use; absorption spectrum of the atmosphere), the pieces I rely upon are more foundational and not (really) in dispute. I would call these “facts,” but even that word gets called into question by philosopher-deniers. I might also expect to see plenty of distracting anecdotes, anomalies, and even scientific literature waved around that pokes holes in certain temperature records or the like. In enormous, heterogeneous data sets, some data will inevitably have systematic errors or point to unresolved anomalies at the margins. Sometimes those little wrinkles turn out to be profoundly impactful, but scientists are weighing the totality of evidence, careful not to cherry-pick, always seeking the underlying truth. In the case of climate change denial, the flow seems to be from ideology to evidence/anecdote rather than the other way around. It’s not objective science, at that point.

I don’t have to be cryptic about where one might find a climate change viewpoint opposed to my own: right-wing outlets really thump this stuff. The issue has become politicized, so that a proper citizen of the right-hand tribe should adopt and parrot what they are told from their own trusted sources about climate change. It is easy to imagine the almost inevitable projection: that such a person would assume the left-hand side—teeming with dirty hippies and scientists—is similarly educated/inculcated and just parroting what their side tells them. Brainwashing accusations fly in both directions.

But I hope I have provided a window into the asymmetry of the situation. I stand to gain nothing from climate change being real. In fact, I think we all stand to lose a great deal as a result. Like many scientists, I don’t subscribe to the ideology of climate change because of some handed-down strategy, but because I see its straightforward plausibility flowing out of a solid foundation of directly-experienced physical reality. I don’t give a fig about what Al Gore says just because Al Gore says it. But when so many people—including myself—have independently arrived at the same inconvenient truth based on observation and physical reality, that’s a powerful outcome.

As a result, it is easier for me to accept the veracity of scientific outcomes than it is for me to embrace proclamations from other domains. I know something about the process. While not every scientific publication stands up to the inevitable scrutiny of the scientific community (especially if appearing in the sensational-leaning journal Nature, as we often joke), I have some basis for trusting that experts in the field will pick it apart if they can. Surviving results are strong, indeed. The fact that it’s not a blind trust in science is what makes science trustworthy at all.

On Who’s Authority?

One last comment is that academics who actually use the term “epistemology” on a daily basis often concern themselves with the question of authority. In philosophy, for instance, the body of work has come entirely from the words of people (authorities)—whose names we remember, and whose pictures will be in textbooks (why the picture of a bearded fellow has any relevance, I’ll never know—maybe the beard certifies authority?). When coupled with a political predilection toward authoritarianism, one can see how a statement of some right-wing ideology (e.g., about climate change or COVID) from an authority figure might be taken for truth.

Science, on the other hand, receives its “authority” from nature itself—not from people. The findings are repeatable and testable by experimenters, with or without beards. We would still understand electromagnetism without Maxwell (bearded), or relativity without Einstein (no beard). These bright but happenstance people were in the right place at the right time to be the first to stumble on these emergent truths, but they did not create those truths—much as continents and islands would be just as well known today without Columbus or Magellan having ever been born. The individual is incidental, and authority is irrelevant. This ties to my last post on the primacy of physical constructs over artificial human ones. It’s not all about humans, people!

Brainwashing, Perfected

I must say that part of me admires the clever and effective manipulation that right-wing media outlets have perfected. Rather than studying political science, international relations, and history, politicos on the right often study marketing, psychology, and communications. The recipe that hooks the audience is to hammer the messages:

- The condescending elitists on the other side think you’re dumb.

- We know that you’re smart (wink; we’re experts at lying).

- In fact, we can trust you to understand the following insight that the elitists will label as conspiratorial: you will know it (in your bones) to be true, being as smart as you are.

- Only we can be trusted to tell the truth: don’t bother even looking at the pack of lies in all the the “lamestream” media outlets, even if they are all oddly and independently consistent with each other (see: conspiracy!).

How brilliant is that? The Soviet propagandists would be proud. The targeted victims/viewers don’t stand a chance against this psychological Jiu Jitsu. They feel belonging, validation, purpose, and—well—smart. Who doesn’t like feeling smart? Having established this bad-faith trust, the outlets can peddle any narrative they want. As long as it has some “truthy” hooks, it will not be questioned. Now, what will they do with this power? Good things, surely.

Views: 7057

Hi Tom,

It's regrettable that you equate the Covid numbers with the climate ones. The basis of those numbers is extremely shaky (just research what a "case" is and how the definition of "cause of death" was changed just for this pandemic; try also to find out the sensitivity and specificity of the PCR tests or why there is no agreed standard for the test – it's impossible to compare ct values from two measurements with different device – etc).

For your main point, I'm curios why the elites that steer those media outlets are not thinking about the consequences of ignoring the effects of our actions. I mean, the two alternatives are a few more "golden" years followed by a catastrophic societal collapse as a result of all the things you've been writing about OR a lot of hard work and readjustment with the hope of escaping the downward spiral.

Thanks,

Andrei

Denial of unpleasant realities is not a left right thing. It's a genetic thing that emerged with behaviorally modern humans about 200,000 years ago.

Note that those who accept the reality of climate change almost universally deny what it would actually take to make the future less bad.

And almost everyone, including those that accept climate change, deny that the real problem is human overshoot.

There is no single 'real ' problem. Industrialisation itself is inherently unsustainable. If we had one billion or whatever number of people

burning sequestered carbon at a rate sufficent to cause the keeling curve to rise each year,we would still have climate disruption and

ocean heating and acidification,just changing at a different rate.

I'm sure there's some population level at which emitted CO2 could be absorbed by the planet. I don't know what that number is but it's probably around 1 billion peasants or 100 million affluent Canadians. After we decide what standard of living we want and after the experts calculate the number of people that can be sustained at that lifestyle for hundreds of years then we know what the goal is and everything else is make-believe and reality denial.

If the civilisation you are envisioning is dependent on sequestered carbon for the energy input necessary to sustain it,it is destined to fail at some point,even if climatic disruption did not exist. Climatic disruption is just one facet of a multi-faceted predicament.

Also, there are no'experts' calculating what level of population we should be aiming for, at some unknown level of energy use per capita, in order to advise the populace what the 'goal' is. That itself is fantasyland stuff. The real world is made up of an ecologically clueless political class, advised by ecologically clueless economists, rapacious capitalists only concerned about short-term profits, and a high percentage of the general populace are just as clueless as the commenters on zero hedge, that Tom mentions.

I fully agree. You cannot have infinite growth in a finite system.

The Keeling curve suggests that those who remain innocent of what you have learned and the outcome you foresee are dominating human behavior.

Correction: another group is contributing: those who know there is a problem but aren't acting. I suspect this group dominates.

It seems to me the task of anyone who sees these problems is to learn and practice the social and emotional skills of influencing others' behavior. Research, publishing, and spreading information aren't influencing others' behavior. It seems to me that anyone pursuing a strategy that doesn't work is a member of the group that knows there is a problem but isn't acting.

What we are lacking is not facts, numbers, or instruction, but effective leadership, which comes like any performance-based skill, through practice, repetition, rehearsal, mistakes, and so on. Again, it seems to me that anyone not pursuing a strategy to lead people is a member of the group that knows there is a problem but isn't acting. This is why I pursue and recommend learning and practicing leadership skills.

The comments on Zero Hedge are complete trash; mostly just racism and sexism. I wouldn't be upset by anything you read on there because it's clearly where the bottom feeders live

[edited to preserve key points]

An article cross posted on Ugo Bardi's Senecca's Effect Blog might be a good little read to crystallize your thoughts on the matter.

https://thesenecaeffect.blogspot.com/2021/12/the-twilight-of-narrative-why-truth.html

If ideals of civility and politeness are a good primary stance to have in debates, I think you're going to have to come to terms with the fact that there are times when you have to take the velvet gloves off. "It only makes matters worse — violent rhetoric only inflame discourse and closes minds further" you say? Not if you knock them out cleanly, in front of everyone and that the result speaks for itself, unambiguously.

Ultimately though, the problem is not one of rationality and soundness of argument — it is one of vision.

The low-brow pseudo-libertarian right sells 'revenge' for capitalism's ongoing train wreck; the low-brow left is in bed with some corporations to sell an impossible [idiotic] green growth; and you … you have to sell organized atrophy; something I can only faintly imagine ever being sold to a civilization already in the tumults of collapse, probably as a chance at salvation for its progeny … m a y b e.

You have a few central bankers tip toeing in the know (superficially anyway), but the truth is so shocking that they are completely debilitated. Being right is not enough.

The sample of people who would be found on ZH, would tend to be Libertarian tech folks (as in, economically right-wing Libertarian), mixed with gold bugs, cryptocurrency enthusiasts, finance folk, and well…generally people who may have ideological or self-interested reasons, for engaging in motivated reasoning on topics that may impact the human-lifetime ("I'll Be Gone, You'll Be Gone…") material/financial interests of them personally, or of their 'tribe'.

They know full well what the real story is, they just don't care – they're part of the debate, to limit the range of acceptable discourse, to control/influence the narrative, to delay any progress/change that affects their interests.

I've been debating similar issues (mostly economic) with Libertarians a lot in the last decade. The main useful thing to come from it, is to learn a topic in detail through debunking convoluted/nonsense arguments (surprisingly useful/educational debunking Austrian Economics, yet also wastes a lot of time) – and to learn the ins-and-outs of the narrative/propaganda – so you sharpen your ability to succinctly debunk every facet of it in detail.

For someone with your knowledge and writing ability, you're far more influential when not engaging with them. A well explained high-level article like this one, though – every now and then, but not often, a very minor/tangential focus – can be useful, even if just for dissecting their narratives a bit.

This is an off-topic question but I hope neither vacuous nor offensive.

I read your blog pretty much by a process which is 'feed reader notices new entry, press button which dumps it into offline article reader, read later in that'. For almost all blogs I read I regard this as fine: they lose advertising revenue etc, but I don't care. For your blog I *do* care: you're doing a good thing and I want to help in any small way I can.

So the question: does it benefit you at all if people read articles on-line? There's no advertising, but is anything measuring things like how long people spend per article and are you using that information? If not I'll carry on the way I am, but if so I'll try and read articles on-line.

Thanks

It doesn't matter. No advertising, no dollars, no harm or benefit to me independent of number of reads or time spent on the site. So enjoy in whatever way you see fit.

Your graph reminds me of a talk I once watched on some streaming service. In it, someone had (numerically I assume, as I don't think it can be done analytically) worked out the change in period over time of the Hulse-Taylor binary from GR. That plot appeared as a slide. They then overlayed the observations of period. And that was just a moment that I thought 'OK, GR really, seriously, works as a theory, doesn't it.'.

Your graph does the same trick[*]: it's very, very effective.

[*] Not 'trick' as in 'fool people' but as in 'extremely neat and effective demonstration'.

Yes, I know that plot well, and agree that it is very effective (a perfect parabolic form, in that case). Oddly, I did not consciously connect the two, but now realize I should have!

And yes, the word "trick" is often used in physics/math contexts to mean a clever manipulation, without implying anything untoward.

Scientists do personally benefit from getting grants. Some only have their job because of grants/fellowship raised. Others get promoted for getting grants, or don't get tenure if they don't. Or get jobs at better universities…. Then it is also easy to see that sometimes there is groupthink and taking alternative non-mainstream positions will mean you won't get that funding or publication. For example, last year, people who proposed that COVID-19 leaked from a lab or was engineered were ridiculed as conspiracy theorists. Or try getting funding for un-orthodox ecological economics ideas from a program geared to mainstream economics… So, the meme that scientists go along with anthropogenic climate change in order to get funding, even if they don't believe in it, isn't that hard to understand, even if it is mostly wrong in fact. Your particular circumstances are more unusual than normal. If you work in climate science areas, anthropogenic climate change is the orthodoxy.

You raise fair points. Success in funding is an important metric for maintaining or advancing a career. And multi-year grants are commonly in the million dollar range (to support a small army of grad students, postdocs, etc.). So when the news reports that Prof. Posh just got $1.6M to study climate impacts on newts, it is understandable how a member of the public thinks: I'd sure like to get my hands on $1.6M, and possibly imagines the new wing that will be built onto Posh Palace. I guess my point of "that's not how it works" was addressing this unsaid misconception: that the scientist is now personally rich.

The pressures you detail do exist. But I would say they do not cripple the enterprise. Science is chock-full of contrarian sorts who bridle at orthodoxy. They may indeed have a little upstream swimming to expose an unclothed emperor, but I have confidence that their voices are still heard and will even win if the evidence is on their side. I know of several such contrarians who set out to knock down climate change, only to be convinced otherwise once they dug in and evaluated the piles of data.

I have confidence that their voices are still heard

But often not believed, at least until the rest of their cohort has gone on "one funeral at a time". Still, to paraphrase M.L. King, the arc of science is long, but it bends toward the episteme.

I think it's important to read the comments of Zerohedge. The comments paint a picture themselves and should lead to understanding as to why civilizations collapse is inevitable . The comment sections of sources like the WSJ and the Financial Times etal are not really that much better, the commenters just use better language to express similar sentiments.

> I suspect many of them would not operate on that plane,

Darwin should have seen the death of religion and yet creationism is still taught and accepted by many. That alone should have been a red flag to understand the indomitable human need to take the nonsensical to heart and must inevitably lead to the "blow up in our face" situation that Carl Sagan suggested was inevitable.

My plan ? Vote Green, ride bicycle, don't fly, why ? to ensure I am not one of those making it worse but also risk minimization, to ensure I am not the first to go by placing myself in a dangerous situation (eg reliance on AC, living in a desert with poor water access, not living on a flood plain or close to the ocean etc some ability to grow my own food etc), much like I do with risk minimization with Covid (mask up, vaccinate and stay away from mass gatherings etc) and I am lucky/privileged to be allowed to do that, my empathy lies with those who can't and I have zero empathy for those who won't and then get caught out.

At the end of the day the mass majority seem to grok there is an issue but not enough to bother even changing how they vote, let alone change how they act (stop flying, driving, etc) This is the group I have most trouble with. The true deniers are something in the single digits ?

Thank you as always for your work Tom. Its been good to know I am not alone 🙂

I have noticed that Zerohedge's pendulum has swung in a generally more 'right' direction the past couple of years. There was a time not so long ago when it featured the work of Gail Tverberg, Chris Martenson, and others who raised such issues as Peak Oil, Climate Change, and the like. Those days seem gone and I've very much come to ignore a number of its posts and certainly the comments on most of its articles.

That factor of 2 has bugged me for years.

Why should ocean and ground absorb *half* of the carbon dioxide we emit, rather than something closer to 1% or 99% as I would have naively expected?

How does this fraction change (or does it) if our emissions increase or decrease?

Can you give a reasonably understandable explanation of this, or point to one?

I don't have any first-principles approach to understanding this bit myself, being reasonably comfortable with the empirical result. I would assume this has been well studied, and that finding literature on it would not be that difficult.

I'm sure it's been extremely well studied—to the point that the technical literature is all about minutiae that you and I don't really care about. What I'm wondering is whether anyone out there has written an explanation that an ignorant physicist like me can understand. Probably I need to find an undergraduate textbook that covers the carbon cycle, or something similar.

I mean, fundamentally, the CO2 absorption rate should depend not on the emission *rate* but on the *total* CO2 concentration, right? And that would seem to imply that if we were to cut emissions in half, the total concentration would stop increasing. Yet I don't think that's correct, even though I don't know why not.

Anyhow, the factor of 2 seems like it must be a coincidental combination of a number of independent factors, and not something we should assume to apply over a wide range of emission rates.

Hi Tom,

As you may remember, I thought the book Limits to Growth was all wrong. Furthermore, I thought most of the other material produced by this movement was wrong too. Systems thinking, declining EROI, peak oil — wrong, wrong, wrong.

I'm astonished that you, a very intelligent man, look at the same material and reach such a different conclusion.

This has been going on for quite some time now. Let me offer the pithiest objection I can think of. By now, the Limits to Growth movement has had serious failures of prediction. Peak oil and peak gas did not happen in 2005. Declining EROI did not cause collapse. Civilization is obviously not following the "standard run" from Limits to Growth.

Why doesn't it make any difference in this movement when predictions fail?

Also, I sincerely hope you don't abandon your successful academic career! Please reconsider! Limits to Growth was a dead end back in the 1970s, and now it's so moribund that people stopped paying attention a long time ago.

-Tom S

It is true that over many years of your commenting on this blog, we seldom, if ever, have agreed on perception of future risks. We're not both right, surely. Treating serious warning messages as "gotcha" falsifiable predictions is taking things too literally and imposing a false sense of certainty on complex situations. I never made the mistake of taking 2005 literally, or 2010, but saw a credible risk of a peak in the coming decades.

Likewise, I didn't interpret Limits to Growth as a set of predictions: that would not be wise or consistent with the LtG work. The text itself tries to make clear that they are not predicting a particular outcome (i.e., don't take any one model run as literal truth/prediction), but exploring and exposing worrisome modes of failure that manifest almost no matter how they change the assumptions and model parameters (within reason). It is simply too early to say that the predictions failed and thus the core message is wrong: nice try. Check back in the year 2080, and if no collapse by that time, then yes: their overall message deserves serious doubt and begs an understanding of what about the overall notion was wrong. But one of their core conclusions, that delayed negative feedback facilitates overshoot, is itself not going to be wrong. To me, it is regrettable that some people (mostly those in the neoclassical economics camp) consider LtG to be "dead" and "moribund." The arguments against it tend to miss (fail to comprehend?) the deeper points and focus on what they see as disqualifying technicalities. What a cost to be "right!"

By the same token, Malthus may yet have his revenge. He was definitely wrong in his timeline, not anticipating the unbelievable revolution unleashed by fossil fuels. I can understand how one might conclude that the same story can unfold again and again, dodging limits before they assert themselves. But I have less faith (once is not proof enough), and prefer a more cautious path: the core concept that finite supplies will not support indefinite growth is not one that I am prepared to call wrong. If the failure of peak oil to materialize in 2005 leads to the conclusion that it is no longer and never will be a real issue, then I guess you're open to future surprises. This is not a game, and disqualifying a well-motivated concept on a technicality (2005 was not a consensus line in the sand) puts us collectively at too much risk.

I feel our conversation has run its unproductive course, and suggest we now go our separate ways. If my message is so disagreeable and lamentable, just shake your head, stop wasting time here, and let time prove me wrong. Because if that's the case, the machinery of the world is already on your side and won't need any help leaving wrong-headed warnings in the dust. And I hope you're right: what a pleasant fantasy. You'll be happier without me. Yes, we're breaking up.

Hi Tom S,

I would distinguish the book Limits to Growth from the broader movement. The book uses pretty cautious language and I don't think it makes any hard predictions that have already been proved right or wrong. We might question its whole program of modeling all of civilization in such simple terms, but as long as the caveats are included I don't see why people shouldn't at least try. I wouldn't call that whole approach a "dead end".

Meanwhile, the "movement" has always had plenty of genuine alarmists. The Ehrlichs come to mind, with their prediction of massive famines that were supposed to occur within a decade or two of 1968, and their refusal to this day to admit that prediction was wrong. They seem to feel they were morally right to raise the alarm, never mind the facts.

I agree with your broader point about the importance of making predictions and then upgrading our worldview when those predictions fail. I believed the peak oil predictions Deffeyes and others were making 20 years ago. Now that those predictions have been proved wrong, I'm inclined to think climate is a substantially more urgent concern than fossil fuel depletion. This is one point on which I disagree with Tom M., whose concern about fossil fuel depletion seems to depend largely on his pessimism about alternative energy technologies. Perhaps we could all benefit by making some hard predictions about the future of those technologies!

It's interesting how the propaganda is pushed so hard that certain premises themselves are then pulled out of the question. Debates on lockdowns take away from the discussion of anything unusual even happening regarding total mortality in 2020 versus previous years.

Headlines on antibody responses by vaccines (just like lipoprotein measurements) take away from the fundamental intention of adaptive immunity and cycles of antibodies. We just "know" LDL=bad; vaccine-induced antibodies=good.

Demonization of carbon dioxide leads to silly debates on temperatures and climates, with absurdly adamant claims of proof based on rare events (eg, f5 tornadoes that don't seem to have any correlation with "warming"). I can make extensive arguments that increased CO2 is beneficial at the cellular level up to the atmospheric level–I *can* do it, but I would never bully others into blindly trusting me, nor am I too sure myself.

Let me get this straight: right wing media outlets have "perfected brainwashing," but left wing media/politicians connecting every storm, heat wave, tornado, and fire to global warming is "good science"?

I've never voted and will never; all media and politicians are trash. I do find it comical though for leftists/collectivists to accuse the right of using *soviet* tactics. Let's look through history and see which systems put emphasis on concepts like "the greater good," subjective/democratic morality, or achieving equality through theft/force/coercion–who's doing that today? Conservatives are like WWE characters: clown-ish but mostly harmless. Leftists have a dangerous obsession with control, via power of the state or herd.

The tragedy of the sapient :

https://www.faninitiative.net/collapse/the-tragedy-of-the-sapient/

This link hits on what I think is a potential contradiction in the narrative in many of us here (myself included). We are both part and product of the natural world, but we are also special in our ability to not behave like other species that will expand until they hit a limit and crash. Since I’m a fan of our species, I’m willing to accept this contradiction. I see recognizing it though as a source of solace if human history ends up shorter that we would prefer.

Hi Tom,

Another great blog post, as always. I discovered your blog about 6 months ago, and I'm similarly struggling to justify my continued career in science. I'm a second year grad student in biology studying microbial ecology and nutrition, and I worry that many of the topics I am working on will be lost/irrelevant post-collapse. I've justified this to myself because an understanding of ecology will be essential to make it through this crisis, especially if I can get my PI to approve a project on earthworms.

The topic of this blog post specifically is also of interest to me. Many in Academia (and the wider world) are brainwashed by narratives about growth. Few see any conflict between this and attempts to fight climate change. How do you talk to your colleagues about these topics and overcome brainwashing? Is it even possible?

Hi Josh; For many years, I lived a dual life, splitting my interests between astrophysics and planetary limits. We operate within a system that expects certain things from us, and we go where the opportunities lie. I would recommend sticking to a more-or-less traditional PhD track, given your current investment. If you can slant it toward relevant ecological concerns, that's a bonus. But you can also live a dual life for a while, using spare time to dig deeper into topics you may be more passionate about. You'll need to maintain at least *some* zeal for your thesis topic, otherwise you risk turning away during tougher times. Once you have a PhD, perhaps a greater menu of options will open up.

It's a big ask to expect people to question pervasive elements of modern life that have been part of society's fabric for generations. I think most just don't think deeply about it, and too easily reject unfamiliar narratives: it's a useful/adaptive filter to tune out ever-present noise. It may take an especially close/trusting relationship to break through the filter. Otherwise, it takes something not far from courage to stand apart from prevailing perspectives. And who wants all that cognitive load anyway? People have lots on their plate already.

[edited to significantly shorten, keeping key points]

I can't defend those who seriously argue that climate change isn't real at all, or isn't related to the amount of atmospheric CO2. […] It's an endless onion of illogical skepticism. Still, I think we can afford to steel-man the opposing argument a little bit.

First, we must recognize that when the public objects to an idea it is rarely for the stated reasons. […]

How many of those [climate skeptics] believe scientists who tell them that sugar is bad for them, that they they should exercise more, or that the earth is round? Probably most of them. So what's their issue with climate change specifically?

I think many "small-c" conservatives notice that climate alarm lends itself to abuse by people with very real and very leftist ideological agendas, who would like nothing more than to remake society beginning with the economy.

When people hear terms like "climate justice" they quickly (and correctly) perceive that it isn't just about cooling the atmosphere, and that inside that Trojan horse are their old familiar ideological foes. People who, while taking emergency action to save the planet, will help themselves to a hearty side-dish of leftist agenda items.

The overall behavior of the climate-activist crowd does very little to allay these fears, I might add.

Reductions in fossil fuel use by some countries alone would […] ensure that the remaining portion of the world population will increase its consumption of fossil fuel to absorb all oil not burned by the conserving nations. […] So, why the push to control the economies of individual nations?

However, much climate "one minute to extinction" rhetoric can (as Jennie Bristow writes in UnHerd) be seen as "the projection of a state of emergency into the years ahead, to provide moral cover for political and economic decisions made by global elites above the heads of their citizens . . . . Indeed, rather than engaging electorates in a long-term debate, we see a global elite hell-bent on wrapping up international commitment in a two-week conference."

[…]

It is natural for small-c conservatives to rebel strongly at any such attempt by internationalists (many of whom have clear ideological agendas) to detach themselves from the electorate. It is a fundamental violation of the social contract.

CONCLUSION: When your ideological opponents (on either side of the political spectrum) claim that an emergency exists and demand wide-ranging powers to fix it, the natural knee-jerk retort is "there is no emergency." But, if climate action could be disentangled from the political aims of "climate justice" then a lot of seemingly irrational climate denialism might just evaporate.

Conservatism is ideologically compatible with the basic actions that would be needed to reduce CO2 emissions. There is nothing more conservative than austerity, old-fashioned preservationist environmentalism, or saving material resources for future generations. "Save our precious oil and other resources rather than burning it all up on frivolities today" is a fundamentally conservative plea. (And action does appear to be possible in red states, if the population trusts the motives of the actors: https://grist.org/energy/in-a-red-state-first-nebraska-plans-to-decarbonize-power-sector-by-mid-century/ )

Thanks for this useful perspective. I, too, marvel at the abandonment of defining conservative principles by the not-really-conservative right. Also, while supportive of efforts to improve justice and equality, I have been a bit baffled by the sideways focus on climate justice. If the Titanic is going down, and lots of lower-class people are trapped below decks by locked gates, I would much rather direct all available talent at saving the whole ship—if possible—rather than worrying over the locked gates just then. One might say that justice/equality issues are "downstream" from the bigger existential problems.

Ah, but much of the available talent is trapped below decks where they can't participate in saving the ship until we release them. Meanwhile others are arguing that we need those folks to stay down there or they'll upset the balance and make it even harder to save the ship.

And presto! Just like that the argument devolves into bickering about contemporary political and ideological questions. And this is just within a single nation.

This is why I can't get too interested in climate change: it's real, but humanity won't be doing much about it.

I maintain that our best hope is to burn our fossil fuels as quickly as possible: if we're lucky, we can use them all up before the population increases too much more. Enough people are going to starve as it is already.

P.S. — Before dismissing the instinctive hesitancy on the political right, one must at least wonder why rank-and-fille activists on the political left have cleaved so enthusiastically to the entire climate action agenda, while giving shorter shrift to other existential environmental problems (such as the imminent depletion of vital non-renewable resources).

Indeed, it is frustrating that the wokiest on the left seem to have eyes only for climate change, which is itself downstream from the overarching problem of how an unprecedented 8 billion people (and growing), whose per-capita resource apettites only increase, can possibly fit within ecological boundaries. Inheritance spending is not forever, and the party can leave the place a wreck.

But I would hesitate to call it disingenuous—just short sighted. Embracing the larger picture might put anti-capitalist activism on steroids, and become an even scarier set of mandates to those on the right. In the end, nature is going to tell us what we can't do. Any activists who carry a similar message will be deeply resented. Based on what I see today, the left will more easily adapt to a constrained life than will the right.

Looks to me like per-capita resource appetites tend to stabilize once people reach a reasonably high standard of living.

https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/consumption-based-energy-per-capita?tab=chart&time=1995..latest&country=JPN~USA~GBR~AUS~DEU~FRA~ESP~CAN~ITA

Okay; so what? An exception at the top of the scale does nothing to allay the larger concern: a small fraction of the 8 billion people will have reached this U.S.-level saturation, so that the cumulative effect of a growing world population—the vast majority of which we would expect to increase per-capita energy use—does the job: we would expect total energy and resource use to go up from here. It's already problematic at today's scale, quite possibly in overshoot. It isn't particularly helpful to nitpick at a technicality that has little or no bearing on the overall story.

Call it a nitpick if you like. In my view we can't get the overall story right unless we first acknowledge the basic facts about world population and per-capita resource appetites. Both are growing rapidly today, but we have a good empirical basis to forecast that both will stabilize over the coming century. And although our per-capita resource appetite is disturbingly high here in the US, most of the world isn't as wasteful as the US.

I acknowledge that none of this would matter if even today's global combination of population and average living standard is unsustainable. Obviously our level of fossil fuel use is unsustainable, but I'm more optimistic about alternative energy technologies than you are. I hope at some point you'll spell out (i.e., show how to do the math for) some of the other reasons you believe things are currently unsustainable.

The story is much larger than energy and fossil fuels. Deforestation, ground water depletion, biodiversity loss, accumulating pollutants, soil degradation, and of course the host of ills from climate change collectively suggest to me that yes: today's global combination of population and average living standard is unsustainable. So to me, the "none of this would matter" remark is on target. Dreams of an even bigger tomorrow seem even further out of touch.

Just because we have not paid the piper yet does not constitute a convincing argument that we can barrel ahead. Overshoot will get you like that. The drastic changes we have made to Earth's ecosystems are really just decades old (the largest impacts). Systems will take time to react. While the jury may still be out, the rumblings from the measures we do have of the environment cannot be called hopeful at this point. So my reaction is to be conservative: treat it like a real emergency. Hard proof means hindsight (thus, too late). The empirical basis you mention is based firmly on past data and trends. Is it capable of predicting the unprecedented? But things really can change, and we see plenty of signs all around. Projections can be misleading when the fundamentals (apparent stability of last few centuries) change under your feet.

I don't doubt the sincerity at all. People just naturally gravitate toward problems that seem solvable with their preferred set of tools (i.e., a hammer looks for nails).

"Embracing the larger picture might…become an even scarier set of mandates to those on the right."

It's all a question of how we approach individual liberty and freedom in this contemplated future. In some sense, conservatives are "fundamentalist" Liberals. Blanket rules to discourage waste of irreplaceable resources (e.g. export bans, or government purchase of large in-ground reserves of non-renewable resources) could attract conservative support, as long as it doesn't involve a totalitarian redistributive government deciding who deserves what.

"Based on what I see today, the left will more easily adapt to a constrained life than will the right."

Maybe. It's a tough call. The right does tend to accept personal poverty without too much political complaint, possibly due to their acceptance of inequality as a natural state of affairs.

The left resents the existence of inequality in any form. This can lead to many good things, but it can also lead to horrific bloodshed in societies under pressure.

Another non trivial factor when considering the sides different tribes take is what people truly value. Of the following, which would be best?

-A world with the same flora/fauna of earth before people, but no people

-A world that learns to live within its limits with people but that does so within a harsh authoritative society with minimal personal freedoms

-A matrix style world where the natural world is decimated but a large number of human minds exist and have agency within some non-natural construct

-A world that lives within its limits that maintains, scientific knowledge and culture but is limited to a much smaller number of people than the world has today?

-An egalitarian world of subsistence farmers without science or “high culture” that is in balance with the natural world with 10x the number of people as the previous world.

This is a valuable way to frame it: thanks. I'm sure others could come up with additional options, but here's the catch: the scenario must necessarily abide by biophysical limits or it can't be a long-term mode of existence. The matrix option aside, your scenarios do build in limits awareness.

Hi, I'm from 2060. After a billion people died from the effects of global warming, we finally decided to build a shit ton of nuclear reactors. Turns out, if you do it at scale, the cost goes down a lot. Our CO2 emissions are currently null. I only wish that we did it sooner and prevented all these deaths. Oh well…

I'm from 2022. I don't mean to be snide, BUT how did you build all those nukes and not burn up the remaining fossil fuels (and dramatically increasing CO2) to build them? Cost isn't a problem – available energy would seem to be. AND how did you avoid proliferation of Nuclear weapons after building all those reactors? AND what are you doing about that long lived waste? AND (one final item) how did the electricity produced by the reactors get turned into the liquid fuels necessary to run everything (farming, transportation). Oh, I forgot, are there 10 or 12 billion humans now?

Sorry if this seems to snarky.

>how did you avoid proliferation of Nuclear weapons after building all those reactors?

How did you avoid it in 2022? Oh, wait, you didn't.

>AND what are you doing about that long lived waste

1. Breeder reactors.

2. The waste doesn't take that much space anyway.

>how did the electricity produced by the reactors get turned into the liquid fuels necessary to run everything (farming, transportation).

Electrification was part of the package.

>I forgot, are there 10 or 12 billion humans now?

No, because demographic transition.

The fact that we have not yet solved the waste problem is an indicator to some that it is an unsolved problem that would only become exacerbated if we scaled up nuclear in a big way. It seems another approach (which hadn't occurred to me) is that the fact that we haven't solved it yet means we don't have to.

Breeders eliminate trans-uranic waste, but not the primary fission products (unavoidable in any fission reactor). So the waste is still there, and "hot" for hundreds of years. That's different from: problem solved. Figure 15.19 in my textbook shows the waste curves. Only one curve is the trans-uranics; the rest are fission daughter nuclei. Also, I have never heard complaints about the volume of waste.

Also in my textbook (Chapter 3), I show the population cost to the demographic transition. It's a population surge, because death rate does down before birth rate does, so that real cases of demographic transition can increase a country's population by a factor of two. It's no snap of the fingers, and comes at a cost (not only in number, but affluence/resource demand).

It's easy to make it sound easy, but hard to actually accomplish the ambitions.

Hi AJ, I'm a visiting space alien. Here's a summary of my report [1] (disguised as an open letter trying to educate a so-called 'decision maker' who thinks the laws of physics are 'optional') on future prospects for inhabitants on the 3rd rock out from its' whatever star. Xylem is spot on: "a shit ton" is by far humans' best and only realistic option. Not in the slightest bit easy, but at least relatively doable.

https://tinyurl.com/NuclearNow

a) Energy density: land, energy & resources needed to build out fission reactors are orders or magnitude less than all other energy supply options, ruling them all out, short of humans reverting back to being agricultural hunter gathers.

b) Weapons: 1 or 2% of humans are psychopathic. This is the root problem. Not what types of weapons & murder methods they lust for. Psychopaths ALWAYS corrupt ALL other humans. Its very easy to build nuclear weapons, or whatever else is available. Solution: ALL psychopaths must first specifically & publicly be identified (e.g. Hare etc.) to stop them obtaining any power whatsoever thereby preventing them destroying everything in their reach.

c) Waste: The current global fleet of 'Light Water' reactors only use 2% of the energy in uranium: Fast Neutron Breeder Reactors can 'burn' the remaining 98% energy rendering the 'waste' safe as background radiation in c300 years. UK has enough 'waste' today to supply it many hundreds of years electricity.

d) Electricity produced used to synthesise chemical energy carriers i.e. fuels for transport & process heat. Also, Xylem's "shit ton" can also supply process heat directly.

e) How many billions of humans? Depends, but a "shit ton" will for certain support more than all other options.

[1] with links to our host's fantastic work – thanks Tom!

Posing as a space alien may seem like a way to acquire credibility, but it can also have the exact opposite effect. What if pursuit of profligate energy at all costs is the very thing that prevents an alien species from becoming long in the tooth and wise? I shudder to think what would happen to our environment if every jackass on the planet had access to as much energy as they wanted. It's not just the psychopaths we need to worry about: plenty of my neighbors would be problematic. Goodbye natural world; goodbye life support; goodbye humans. What evidence do we have that humans will make wise choices when money is to be made by doing unwise things? It is unclear to me whether nuclear is a step toward long-term sustainability or away from it.

Tom, the 'space alien' perspective was an attempt at a pinch of humour, to draw a larger perspective, (e.g.'Pale Blue Dot') rather than accrue any personal 'credibility' (or plagiarise Sagan). Also as a kid, always asking 'why?' I was often dismissed by my parents as an odd sort of space alien (turns out its partly ASD). I agree, physics would almost certainly make it impossible for any life form to leave their planet(s) of origin, let alone be also endowed with however many cubic miles of hydrocarbons lurking underground to fool them 'Tom Swift' stories are true! No wonder Dyson hated the spheres idea named after him. I also very strongly agree with you that humans and our psychology makes us our own worst enemy. The point I am trying to make is that so far (all other factors aside) human civilisations have been climbing 'up' the energy density ladder, not down it, as the 'Greens' would have us believe is a desirable and possible near future. Without nuclear or hydrocarbons humans will for certain crash back to medieval life, if we can survive at all burning wood with no forests left, which may or may not be sustainable or desirable, or indeed needed. I am an optimist despite our psychological endowments, I don't think a nuclear powered future would enable every jackass on the planet access to as much energy as they wanted, since nuclear is also severely limited by physics and resource access.

Thanks for elaborating. The bit that makes my knee jerk is the attraction to a narrative around a single parameter (energy density, in this case). The ladder climb will be true until it isn't, for one thing. Patterns break at some point. Every day, we wake up—until we don't. If we do climb the next rung to nuclear, does that guarantee another rung to follow, despite no known physics to support the continued narrative climb? Given the difficulties and downsides of nuclear energy, I am less sanguine that we'll continue the climb. Outside of energy, so many destabilizing influences are in the making as 8 billion people strain ecosystems and resources beyond breaking points (classic overshoot dynamics) that maintaining a high-tech nuclear industry reliant on global supply chains may be hard to pull off. I'm not saying it won't or can't happen, just that I am less wedded to the continuation of an appealing narrative.

Hi Xylem!

You know, I've always suspected that most environmentalists lobbying for climate action know we face predicaments beyond just climate change (or peak oil). Energy is only the first telephone pole we're about to crash into. Water from fossil aquifers, topsoil, phosphorus, and industrial metals and minerals of many kinds are being rapidly depleted. (And not a moment too soon, given the ongoing destruction of earth's ecosystems and, by extension, its long-term carrying capacity.)

As von Bismark said, "Politics is the art of the possible." That being the case, what can we realistically get out of industrial civilization before it consumes itself?

Some alternative energy sources seem like a good bet, and climate change seems like a good reason to develop them. Just don't make the mistake of thinking that climate change is the *only* problem we face.

Alice F. has a good article today. The comments on her site are disabled. I think

Alice underestimates the climate disruption aspect. Fossil fuels are not the only source of increasing CO2 levels. The enormous tundra peat deposits,if they are oxidised by burning or decomposition,is another . The effects of climate disruption

are evident right now,and will inevitably get worse. The melting of the permafrost regions is occurring right now,and a positive feedback loop is probably already occurring.

https://energyskeptic.com/2021/climate-change-deniers/

Alice is hitting all the right buttons. An excellent read. Unfortunately, we are an increasingly urbanised world culture and our populations (not just Western) lack the skills and information (and I suspect drive) to survive outside the urban cocoon, when TSHTF. The line should be "Copulate, but don't Populate".

I just found this. ( If you were intending to do a separate post on this, and don't want it on this thread,please delete)

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2214629621003327

I did have a short post announcing PLAN (and the paper) in early November: https://dothemath.ucsd.edu/2021/11/finally-a-plan/ but will let your comment serve as a reminder for those who may have missed it.

Tom, thank you for a great post.

My pathway has been different, but I have worked at the same issues since 1972.

In a sane world, every human would be cooperating to stave off extinction; not only of humans but of all complex life on this planet.

Climate change is not the problem, but one of several symptoms of the problem, which is a global culture that rewards and encourages the worst in human nature, particularly greed. The fossil fuel and car industries had accurate predictions that their activities would lead to catastrophic climate change, and instead of acting to prevent it, they invested billions of dollars to ensure it would happen. How sane is that?

Equally serious is the fact that we live on Poison Planet. Every living being on this planet has toxins and carcinogens inside them, including the decision makers of the companies that make and market these substances. How sane is that?

Plastics killing birds and marine life is an externality. Dealing with plastic waste is good for the GDP, showing what an idiot measure that is.

Rather than writing an essay in a comment, I'll just say I have many resources at my blog, Bobbing Around.

Keep up the good work,

Bob

In defence of authority: the major areas that impact us, finance, medicine, environment, are all way too complicated for us to test conclusions ourselves. Thus, I spend most of my time seeking credible authorities. People like you, Tom, who have done the work or have the education, or the intelligence, to understand something in depth.

Nothing wrong with deferring to authorities. I’d argue it’s necessary.

I see your point. And I guess I do defer to scientific consensus (more so than individuals), as I believe this tends to reflect the ultimate authority of nature. But too many people make claims on authority. I don't see myself as an authority, and cringe at the thought. I guess that's why I tend to lay out the case and caclulations as I do in many of my writings: allowing others to retrace my steps and own it themselves in a way similar to how I build my own understanding.

Greg,

The key qualifier in your point “credible”. If credibility is based on consistently demonstrating the ability to observe and follow the scientific process, then we are all in violent agreement. We could also differentiate deference to expertise (or expert authority) from deference to authority of any other type . Expertise here is understanding the data and science on a topic at a high enough level.