This is part of a series of posts representing ideas from the book, Ishmael, by Daniel Quinn. I view the ideas explored in Ishmael to be so important to the world that it seems everyone should have a chance to be exposed. I hope this treatment inspires you to read the original.

Chapter ELEVEN contains my favorite section (#4) of the book, exposing Taker biases on Leaver life: a huge hurdle in knocking loose Taker mythology. This chapter is presented in six numbered subsections, beginning on page 209 of the original printing and page 225 of the 25th anniversary printing. The sections below mirror this arrangement in the book. Section 4 is packed with incredible content, so receives a bit more attention. See the launch post for notes on conventions I have adopted for this series.

1. A Nearly Final Rejection

Offering blankets to a cold Ishmael on a rainy afternoon, Alan receives little in the way of gratitude, and instead is challenged by Ishmael as to why he wishes to learn the story enacted by the Leavers. Alan repeatedly offers lame reasons that offer insufficient motivation to Ishmael: why should he bother?

Ishmael has finally had enough, and asks Alan to go away—to come back only if he can produce a compelling-enough reason to go on. Alan stubbornly declines, finally suggesting that the “children’s revolution” of the sixties failed because it was not enough to reject the story enacted by one’s culture. Without another story to be in, the protest is aimless. We need to know the Leaver story so that we know at least something exists beyond the invisible bars of our cage.

Ishmael is finally satisfied enough to continue.

2. To Become Human…

Just as the Taker mythology is about human destiny and place in the world, the Leaver mythology operates on similar turf. Ishmael repeats a previous point that humans became humans while enacting the Leaver story. But Ishmael stumps Alan with a seemingly identical question: “How did man become man?” They stick a pin in that question while Ishmael devises a new approach.

3. Nasty, Brutish, and Short

Ishmael asks how Takers might characterize the agricultural revolution: what sort of event was it? Alan reports that Mother Culture classifies it as a technological event, rather than a change in cosmology or cultural attitudes. [Takers unimaginatively assume that the only alternative to their own cosmology amounts to nihilism.]

Modernity’s cultural attitude is that life before the revolution:

…was devoid of meaning, was stupid, empty, and worthless. Pre-revolutionary life was ugly. Detestable.

Indeed, Alan remains under this impression. Asked who in our culture might have a different view, Alan hazards that anthropologists might. Right: the ones “who actually have some knowledge of that life.” Yet, “Mother Culture teaches that that life was unspeakably miserable.”

Asked if he could fathom trading modern life for a pre-agricultural lifestyle, Alan admits that he cannot. Meanwhile, Leavers exposed to modernity have consistently tried to return to their Leaver lifestyles—often rendered impossible by the destructive acts of Takers.

When Alan tries the standard line that Leavers just didn’t know any better, Ishmael counters that Indigenous people who practiced agriculture abandoned it when conditions allowed (using Plains tribes as an example). Mother Culture would claim, patronizingly, that they didn’t really understand the benefits of agricultural life, as returning to misery is unthinkable for one who truly understands.

Ishmael suggests that this cultural “fear and loathing of the Leaver life” is at the heart of our kamikaze quest that risks destroying the world before allowing that “dumb” Leavers might possess wisdom worth absorbing. Ishmael’s goal is to define what revulsion the agricultural revolution was revolting against. Gaining this insight will make it easier to come up with the premise to the Leaver story.

4. The Misery Misconception

Finally, we arrive at my favorite section, loaded with key insights (I especially love the role-play part).

After shrinking into his blankets with shuddering sigh, Ishmael rallied to ask what necessitated the revolution. Alan said that it was a prerequisite for “getting somewhere,” by which he meant securing all the trappings (comforts, conveniences) of modernity.

But, it goes deeper than this, because even the hundreds of millions of Taker people living in deplorable conditions and for whom these luxuries are unattainable would still express a preference for Taker life over what they understand to be Leaver life.

They all believe profoundly that, however bad things are now, they’re still infinitely preferable to what came before.

What Ishmael seeks from Alan is a deep dive into the whisperings of Mother Culture, to dredge up what our culture says about the horrors of life before agriculture. After a superficial response, Ishmael prompts Alan to think hard. A few minutes later, Alan shares an image that floated to the fore [which I also described in Desperate Odds].

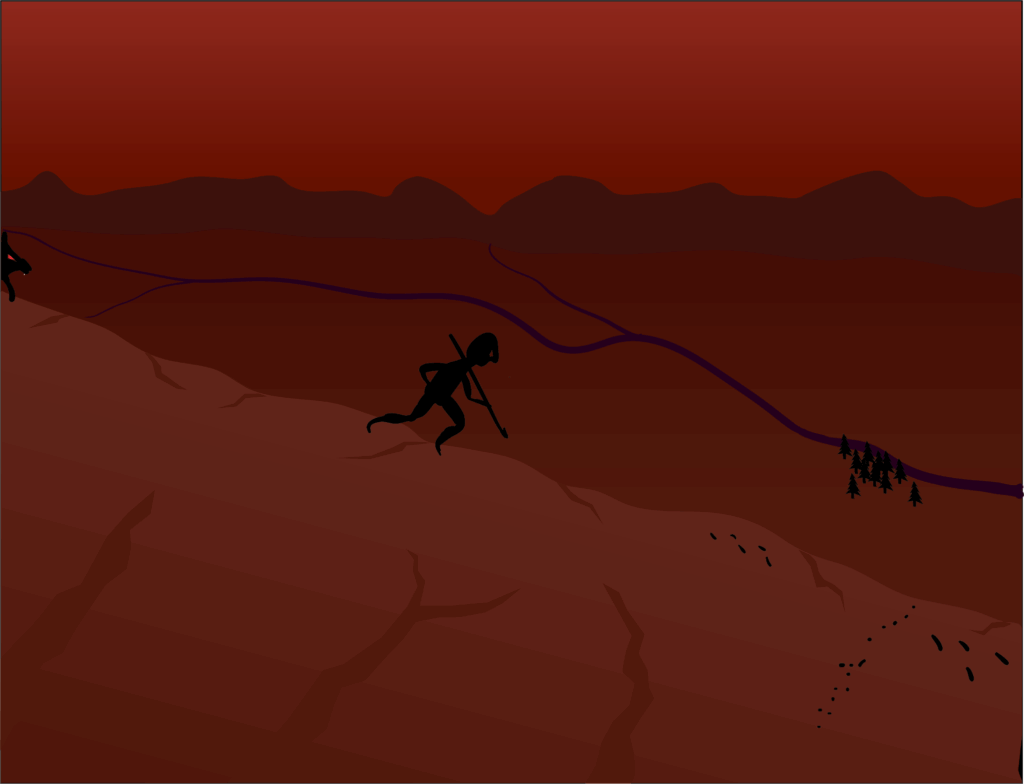

A scrawny man labors along a ridge in dim lighting, as if in perpetual dusk. His burning hunger drives him in pursuit of prey, bent-over in search of tracks as night closes in. Compounding the danger of starvation is a menace from behind, in the form of ravenous beasts closing in with sharp claws and bare fangs. The scene has a never-ending “treadmill” quality to it, where the man remains:

…forever one step behind his prey and one step ahead of his enemies.

I tried to capture this moving imagery in the graphic at the top of this piece. The alliterative title, “Hungry Hunter, Himself Hunted” could just as well have been “Famished Forager, Fearing Fangs.”

The sharp ridge conjures the knife-edge limbo-land of survival in which this desperate creature lives. The treadmill aspect is important, too: never getting anywhere, but having to keep moving lest he starve, get eaten, or just fall off. Ishmael sums up this vision as “a very grim life.” [I feel that this metaphor perfectly reflects our cultural impression.]

Ishmael dispels this fabrication as pure fiction:

Hunter-gatherers live no more on the knife-edge of survival than wolves or lions or sparrows or rabbits. Man was as well adapted to life on this planet as any other species…

In fact, the flexible adaptability of humans—being omnivorous, intelligent, and handy—favors human survival in conditions that would “do in” other species. Plenty of studies reveal that hunter-gatherers remain well-nourished spending only a few hours of average daily effort on the securing of food—even in lands we might characterize as “hardscrabble.” Their lives contain far more leisure than do our own. Moreover, humans are not a preferred prey of any other animal on Earth: we’re lucky that way. The vision of horror is flat-out wrong on both counts. It’s not at all how an actual hunter-gatherer would describe their life. [I have a post examining life expectancy data for hunter-gatherers that puts daily risk of copping it at 0.005% chance for prehistoric adolescents: low enough to feel just as invincible as do today’s adolescents.]

Alan’s repulsion for the Leaver lifestyle stubbornly persists. To probe further, Ishmael presents a hypothetical box with a button that, if pressed, sends you (and your family) back to prehistoric times, integrated into a community and privy to both the language and skills. Would a completely destitute person of modernity with no prospects elect to press the button? Probably not, Alan believes. So, Mother Culture must fill our heads with horrific notions of the distant past.

Ishmael sets up a role play exercise between Alan as a Taker missionary and Ishmael as a hunter-gatherer. The awesome demeanor of the hunter-gather is so chill that I will take the liberty of naming the hunter-gatherer Xóchitl—a name of Aztec origin. I don’t think Ishmael would object to playing a female role, do you? The situation is that a Taker culture wants to make use of Leaver-occupied land, and the missionary is to explain to the hunter-gatherer the sense in abandoning their lifestyle to join the superior Taker way. The sales-pitch begins:

This life of yours is not only wretched, it’s wrong. Man was not meant to live this way. So don’t fight us. Join our revolution and help us turn the world into a paradise for man.

In other words: become a human supremacist like us. Join the Human Reich. Do we get arm bands?

So, Ishmael (as Xóchitl) challenges Alan to “Explain to me why the life that I and my people have found satisfying for thousands of years is grim and revolting and repulsive.” To help Alan out, he (she) begins the dialog in this vein, using an endearing (teasing?) moniker for the missionary (meaning “boss” in Swahili):

Bwana, you tell us that the way we live is wretched and wrong and shameful. … This puzzles us, Bwana… But if you, who ride to the stars […] tell us that [this is so], then we must in all prudence listen to what you have to say.

I love the starting position of openness and respect. Even when Alan’s answer insults the Leavers as “ignorant and uneducated and stupid,” Xóchitl responds with tremendous poise: “Exactly so, Bwana. We await your enlightenment.”

What ensues is a series of complete bafflement as neither seems to understand the other’s point, often represented below as a back-and forth within a paragraph (context sorts out who says what, well enough). I can’t do it justice here, so encourage you to read the original.

Telling Xóchitl that she and her people live like animals is simply confusing to her: they live as all others live. Do all animals, then, also lead shameful lives?

The conversation moves to control: lack of control over food. Xóchitl is again confused, because hunger is easily satisfied by finding something to eat. It sure seems to be in their control when to eat. But more control could be had by planting. Why is it relevant who plants the seeds that will be planted regardless? If you took control, you’d be assured of its growing. But we are already assured of its growing. Xóchitl goes on to explain that they live in a world filled with food that isn’t going to suddenly abscond. And here is a crucial point: if the food were not reliably available, we would not still be here to have this conversation. Deny that!

Alan continues to promote the virtues of control: providing the ability to decide on the abundance of various crops. Xóchitl again can’t see the point when their food is already in sufficient abundance. Why toil so hard for no reason?

But what about when something is not available? Now I’ve got you: what do you do then? Well, eat something else, I suppose. Doesn’t the same thing happen to you masters of space, since seasons apply to all of us? No: that’s exactly it. We can eat anything we want all year-round, thanks to the technology of canning.

Xochitl is intrigued, having heard of this method. When asked how much effort goes into the process, Alan proudly speaks of the hundreds of people involved in the mining for metal, securing fossil fuels for mechanized agriculture, assembling huge tractors and combines in factories, building trucks, paving roads, packaging, maintaining retail spaces, facilitating transactions via financial institutions, and on and on [I made up my own list here; differs in the book]. Xóchitl can’t help but to think this is insane. All this colossal effort to banish minor disappointment over the lack of a yam! When Xóchitl can’t get a yam, she is happy to get something else.

A frustrated Alan says that Xóchitl is “missing the point,” to which Xóchitl readily agrees. Alan tries a higher-altitude perspective. If not in control of your own food, then “you live at the mercy of the world.” It’s irrelevant that you’ve always had enough. Lack of control is no way for a human to live. “Why is that, Bwana?”

Alan tries again, this time on the hunting front. Maybe you bag a deer, but maybe you don’t. Then you’re stuck. If we fail to get a deer, we just “snare a couple of rabbits.” Alan decries the fact that they are forced to settle.

And this is why we lead shameful lives, Bwana? This is why we should set aside the life we love and go to work in one of your factories?

My translation: all this so you can live in a perpetual state of toddler-dom—to avert a tantrum when a deer is not to be had? Being sentenced to a factory job seems like such a harsh atonement for the wretched sin of settling for rabbits.

Alan doggedly persists. What if you get no rabbits? “Then we eat something else, Bwana. The world is full of food.” Alan presses on. What if there’s not? Nothing is guaranteed. What about drought: don’t you have those? Xóchitl is quite familiar with droughts, explaining the dwindling grasses, fruit, game, and predators. “If the drought is very bad, then we too dwindle.”

Aha! Check mate! You die!

Is it shameful to die, Bwana?

Alan explains that the major error is trusting the gods to take care of you. They don’t always come through [what I call: fairness, fairly distributed]. To be human is to only trust ourselves with our lives—not the unreliable gods. Xóchitl is very disheartened to hear this. It seems to her that living in the hands of the gods for millennia has worked out well enough, providing satisfying lives. The gods can see to the planting of the garden, allowing for Xóchitl a life of leisure. And again here’s the real kicker: if the world did not provide adequate sustenance all through deep time, we would not be here today!

This does not satisfy Alan. Yes, they are here. But they lack clothes, an air-conditioned house, a car, and a job—all because of the lamentable choice to live in the hands of the gods. Alan is onto something. The gods do not deign to differentiate between humans and animals, treating all essentially the same way [they don’t for a second subscribe to human-supremacist ugliness]. Refining the thought, Alan admits that the gods provide enough for humans-as-animals, but will not provide the extra it takes to be fully human.

Xóchitl is dismayed to learn that the gods would deprive humans of anything essential:

But how can that be, Bwana? … that the gods are wise enough to shape the universe and the world and the life of the world but lack the wisdom to give humans what they need to be human?

Well, that’s what you get for ceding yourselves to “incompetent gods” [gods too dumb to appreciate human supremacy]. Those gods only provide the bare minimum of necessity. By taking control of planting your own food, you can obtain “more than you need.” Xóchitl is unclear of why we need more than we need.

Alan finally puts his finger on it: securing more than is needed through our own labor allows us to “thumb our noses at [the gods].” Because, when the gods send drought, you can access your stores of food and laugh at the gods, saying to them: you can’t squash me because I am no longer in your hands!

5. Almost Gods, But Not Quite

The role-play delivered greater clarity about whose hands Takers live in. Ishmael probes further: by living in your own hands, you presumably have the control necessary to prevent your own extinction.

Alan admits that we are not yet in total control. We could not, in all likelihood, survive the sixth mass extinction we unwittingly spawned. We will only be safe when we have managed to pry the entire planet out of the hands of the gods. Complete freedom from the power of the gods awaits, once we control everything, in absolute [totalitarian] rule. [Cue maniacal laugh.]

6. Divergent Worldviews

Ishmael and Alan have a brief discussion about Christian attitudes toward distrusting God to provide, even though one passage in the bible has Jesus advocating exactly this sort of faith. Actions betray the true belief.

Undeterred by the persuasiveness of the role-play, Alan firmly expresses the side he’s on: “I can only think that hunter-gatherers live in a state of utter and unending anxiety over what tomorrow’s going to bring.” Ishmael counters that any anthropologist (who might actually know something) will refute this notion. Hunter-gatherers tend to be, in fact, less stressed than the average member of modernity. No one can withhold their food for lack of money, job, or papers.

The exercise has clarified that the revolution is meant to put us beyond the hands of the gods. The Takers are therefore “those who [believe they] know good and evil,” while ” the Leavers are those who live in the hands of the gods.”

Next Time

In the next installment, Chapter 12 rounds out the lessons between Ishmael and Alan.

I thank Alex Leff for looking over a draft of this post and offering valuable comments and suggestions.

Views: 3104

Yes, good stuff.

I always remember a study of Masai tribes in Africa by anthropologists.

They 'worked' 15 hours a week, tending to animals, getting food, water, shelter; they 'worked' another 15 hours a week doing family care. That's it. The rest was leisure time. The trick was of course, that the necessary work was done together in groups, so it wasn't massively exhausting or dangerous. This where the image of the solitary hunter on the knife edge ridge is wrong, because it wouldn't be one human running from fanged beasts whilst chasing lunch, it would be a whole bunch of humans working together to get lunch and ward off dangers.

And notice how the family care was as much time as 'working'. Tending to the children, looking after any elderly and disabled, making sure their needs are met, and so on. The atomised families of neo-liberalism don't do that, we pay a fortune for random strangers to do it, mostly carelessly.

Another example, was an 18th century paper by some rich English factory owner, complaining that the peasants slothed with their pig, about doing only necessary stuff which averaged out at 28 hours a week 'work'. How much better (for him and his profits) it we could take his enclosure off him and force him into a factory for 60 hours a week.

The concept that we all must work for a living is one the biggests cons ever perpetrated on humans by a minority of humans. We are not evolved for this society we live in, hence the mass of mental health issues in western cultures especially. I think deep down our subconscious knows the leaver theme, every now and again it pops out and terrifies people stuck in the taker matrix.

"Another example, was an 18th century paper by some rich English factory owner, complaining…"

This reminds me of an essay by Bertrad Russell called "In Praise of Idleness." In it he mentions a rich person saying “What do the poor want with holidays? They ought to work.”

https://harpers.org/archive/1932/10/in-praise-of-idleness/

He talks about how there's entirely too much work done in the modern world, and that leisure should be given as much importance as work. It's well worth a read.

I'll add that many of the "tasks" constituting "work" for hunter-gatherers are activities we elect to do when we are released from work (e.g., on vacation): fishing, hunting, trekking, gardening, canoeing/kayaking. What does that tell us?

Yes exactly. Imagine how much fun going hunting would be. Or the thrill of coming across a tree laden with ripe fruit.

And when young children play "hide and seek" they are practising skills needed by the hunter-gatherer, not by the office worker.

True, but an awful lot of people seem more inclined to inhabit “Screen World “in their down time these days – phones, TV, gaming – rather than engaging in outdoor activities. This is another increasingly insidious layer of modernity: most of us are now hard-core dopamine addicts, as Vanessa Machado de Oliveira suggests in “Hospicing Modernity”. How many of us can handle sitting still on a beach admiring a sunset for any longer than a few minutes these days? I suspect that lots of people might happily accept that Leavers’ existence was/is not one of a constant state of hunger and fear. Instead, they would dismiss it as “boring”, lacking the constant stream of novelty and excitement that modernity delivers. We are prisoners and addicts, no?

"most of us are now hard-core dopamine addicts", Is this why there is an increase in ADHD? (I am writing as someone with it). In earlier times, people with ADHD would have been seen as energetic or people would think "their head is in the clouds" but modernity (especially the past 50 years) has made it a lot worse.

The role-play section is my favourite part too. And in the book "I, The Aboriginal" (recommended by Quinn) a similar thing happens between a few sailors and Australian aboriginals at a navy camp.

The aboriginals see an airplane drop food supplies to the camp and are completely baffled because they're surrounded by food: fish, turtle eggs, wallabies, yams, lily roots, goannas, and grubs. Upon getting to the camp, not only do the sailors say that this food drop was their first proper meal in a week, but actually offer oranges to the aboriginals, thinking THEY wouldn't have had a proper meal for months!

The aboriginals (feeling patronized) tell them that food is everywhere, and they actually go and get a dozen fish back to the camp. But bafflement resumes when the sailors reveal that they've been getting sick because there's only brackish water to drink. The aboriginals laugh and dig a hole which, to the shock of the sailors, fills up with clear fresh water. Sailors learn that they were standing on an old sand-well. If this wasn't enough, one of the aboriginal (author of this book) was a trained medical assistant, and helped the sailors with the modern medicine he was carrying.

Later, the aboriginals went and returned with even more food of various other kinds, including a snake and a lizard, which the sailors declined. After leaving the camp, the aboriginals laughed about how these "whitefellers" can build airplanes, cars, refrigerators, bombs, etc. but can't find food or even water—and they were sitting on it.

Tyson Yunkaporta in Sand Talk makes the point that we must have been doing something right to have evolved our complex brains.

Rather than being a brutish existence, our ancestors must have had access to a good quality diet over a very long period of time for our brains to have evolved.

You should read Nutrition and Physical Degeneration by Weston Price.

It has plenty of photos that show isolated communities that are free from degenerative diseases, especially tooth decay, because they rely on locally available foods that are high in nutrition. They know what to get and from where, to not only be well-fed, but also, healthy.

It's a great book that visually destroys the myth that the so called primitive people, lacking modernity's help, must have been starving.

Thanks. I'll check it out👍

I totally missed the "role play" section in the book🤔🤷?

Was it only in the 25th anniversary edition?

It was in the original, and made a big impression on me when I first read it (from an old, used, original printing).

Hmmm. I'm going to have to take another look.👍

@tmurphy

Just a slight query.

The choice of Xóchitl as the Leavers name in the role play.

But weren't the Aztecs/Mexica a Taker culture, on a technological level similar to the Sumerians? 🤔

But then again, what's in a name🤷?

Yes, the Aztecs are not an ideal choice by any means—although it is my understanding they did not have the Taker flaw of "ours is the one right way to live" and did not impose their systems on the surrounding people. Nonetheless: A) we would still call Aztecs "Indigenous" for what that's worth; B) I don't know any Leaver names; and C) the "so chill" connection was too juicy for my to pass up.

Tom, though I have read the book at your instigation, I enjoy reading your summaries too. I appreciate carefully chosen words to impart knowledge, as I think Ishmael and Alan do. (both the Socratic aspects of Quinn?)

Here, I much like the argument: "if the world did not provide adequate sustenance all through deep time, we would not be here today!" – quote the Leaver. In truth, if they lived their life wrongly, thoroughly modern Taker would not be here either! – somehow we keep tending to ignore this and relive the same blissful ignorance with every generation.

Don't we, for instance, convey the same to our parents and the generation before, that "You are sooo ancient, you don't have the clue how to live today: your ways and methods no longer apply. But we, we know how…" (because we can adapt and you can't?)

"Ishmael and Alan have a brief discussion about Christian attitudes toward distrusting God to provide, even though one passage in the bible has Jesus advocating exactly this sort of faith. Actions betray the true belief."

I don't remember this section in the book or the referenced passage in the bible. Would you mind explaining more? Thanks!

The quote:

Far and away the most futile admonition Christ ever offered was when he said, 'Have no care for tomorrow. Don't worry about whether you are going to have something to eat. Look at the birds in the air. They neither sow nor reap nor gather into barns, but God takes perfect care of them. Don't you think he'll do the same for you?' In our culture the overwhelming answer to that question is, 'Hell no!' Even the most dedicated monastics saw to their sowing and reaping and gathering into barns.

A quick Google suggests this is Matthew 6:26 (Ishmael 11:6). It is striking how Ishmael-like this odd piece of incongruent (for the bible) advice is. It's an admonition of agriculture, and advising to live in the hands of "the God."

A portion of the "Sermon on the Mount".

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sermon_on_the_Mount

A missionary is walking along a beach and meets an indigenous hunter/gatherer laying on the sand drinking coconut milk.

Missionary: "What are you doing? You are wasting your life lazing around on the beach. Why don't you pick all the coconuts you can find."

Enkidu: "Why would I do that?"

Missionary: "Then you could sell them and make money."

Enkidu: "Why would I do that?"

Missionary: "Then you could build a real business. You could hire other people and become rich."

Enkidu: "Why would I do that?"

Missionary: "Then, after 30 years or so, you would have enough money to retire, and you could sit and relax on the beach all day!"

…humans are not a preferred prey of any other animal on Earth…

Correct. Jim Corbett who stalked many man-eating tigers and marn-rating leopards in the foothills of Himalayas has noted that these predators normally ignore humans and turn to them only when they lose their ability to hunt wild preys due to accidents, sickness or old age.

"The role-play delivered greater clarity about whose hands Takers live in. Ishmael probes further: by living in your own hands, you presumably have the control necessary to prevent your own extinction."

Yet, because we decided to live by our own hands, we are facing more existential risk now than at any other time in history.

Right: and Ishmael was poking here—goading Alan to admit that unless we establish absolute control over everything (a juvenile fantasy), we risk a monumental crash-and-burn. Thus: just stop trying. We're embarrassing ourselves.

I really appreciate how you're breaking down Ishmael in such a structured and thoughtful way—it’s clear you’re passionate about the book’s message. Chapter Eleven is definitely a pivotal moment, especially in how it challenges readers to reconsider the deeply embedded assumptions of Taker culture. Section 4, in particular, does a powerful job of reframing our understanding of Leaver societies. Thanks for putting in the work to share these insights—this kind of reflection makes the book’s core ideas much more accessible and invites deeper engagement from readers who might not have picked it up otherwise.

Happy to see comments are still on, though apologies for popping in late – your enthusiasm for this chapter was contagious and I spent extra time percolating on it post-reading, and appreciating all the other insightful commentary.

My first thought this time around was about Taker projections – that the grim descriptions of life, in constant survival mode on a ceaseless treadmill, sound a lot more like Taker existence than Leaver, even with all our fossil-fueled comforts (though I'm starting to think 'trappings' is the better word for it) – and would also fit more with the toil and constant chores and maintenance of a totalitarian agriculture lifestyle rather one where you take what comes. This misperception of Leaver life is SO pervasive – it's the foundation for much of modern self-help and psychology, that we were unsafe then because, lions; we are safe now; and it's just your 'monkey mind' telling you you're trapped. It's even in environmental circles – I just finished an otherwise thoughtful book that described how our pre-agricultural ancestors "endured" their horrible, insecure lives to become us, and that our misguided desire for 'safety and security' is to blame for our subsequent suffering, which made no sense to me at all but then again, I'm not a Buddhist. Read any actual account of tribal life, like Land of the Spotted Eagle, and the extent of the con becomes clear. Or any one where the other side gets to express their opinions about Takers, for once: two-faced, loudmouthed, foul-smelling liars with sickly farmed animals, vermin-infested lodgings, itchy uncomfortable clothing, and an excess of facial hair. Perhaps a few kernels of uncomfortable truth?

On the topic of food, and preference for specific foods – I've come across more than one anecdote about how Takers assumed Leavers were starving because the Leavers were eating insects as part of their diet! I also vaguely recall Quinn, in a Q&A, expressing astonishment at how attached Takers were to being able to satisfy their particular food cravings, that this was so instrumental in their lives that they tend to shrug off the massive consequences – or as the dialogue points out, the insanity of the work involved so you can have a yam whenever you want. I was not surprised by this, as I worked in American restaurants for years, and at this point I wonder if it's beyond spiting the gods. The cultivation of addictive foods/grains and eventually alcohol as a theory as to why Taker mentality, totalitarian ag and that particular civilization spread, and why it still stands today, was an explanation that made some sense to me as to why people stand it, especially those on the bottom. As Quinn later points out, drag your quota of stones up the pyramid and you can have a beer, or ten. Hurray for modernity!

I guess it's obvious, but I would push that button in a heartbeat.

Excellent reflections. Indeed, if Leavers were miserable and starving, they'd be like drowning rats scrambling and clinging to the boat when Takers make an appearance. Finally, "real" food! But no: they resisted with all they could muster, quite satisfied with their way of life. Also, Europeans who were meaningfully immersed in Native American lifestyle tended to choose it over the modern life. Meanwhile, Native Americans exposed to modernity tended to want to go back to their beloved life. Often, that was made impossible. Would starvation and misery produce such reactions?