Daniel Quinn returned to the theme that “food makes babies” so often in his writings that it would seem he was continually dissatisfied either with the clarity of his case, or with objections people had, or both. I get it. I often return over and over to the same thorny themes, each time thinking I’ll finally nail it. The exercise is as much for improving internal clarity as anything.

Many of the comments following my coverage of Daniel Quinn’s Ishmael focused on the food–baby issue. The more recent post on The Story of B dwells on the topic as well, so I figured it would be worth dedicating a post to the matter, trying to covering all the angles.

The statement that increasing food production leads to increases in population touches a nerve for some people, which is what makes it a valuable topic to explore. For some, the statement seems to be an affront to their notion of control. It implies that humans are “no more than” animals, which takes direct aim at our most prized mythology: human supremacism—relating to Ishmael’s second dirty trick: that we “evolved from the slime”—barely tolerated by modernists, but only in a narrow technical sense.

Now, the objections are not without demonstrable legitimacy. In this post, I will start with the basics, point out key objections, then see what we can make of it.

Food Does Make People

We start with some obvious and incontrovertible facts. As for any animal, humans are built out of the food we eat. It’s where the atoms come from. Humans have many holes (including pores) out of which to lose mass, but only one mouth-hole for adding mass—in the form of tasty assemblies of atoms. Not just any atoms will do, but generally those biologically arranged into sugars, fats, and proteins. No rocks for me, please.

I cant resist pointing out that the simple act of breathing constitutes a significant mass loss mechanism—easily into kilogram-per-day territory. Not only do we take in O2 and breathe out CO2 (see what we did there? Kicked out a carbon atom!), but we also lose water molecules in our humid breath—made visible by condensation in cold air.

It is obvious, then, that if human population explodes—as it has—it must necessarily be accompanied by an increase in food supply going into mouths. We’ll get to causal direction later.

Mouse Experiments

Daniel Quinn effectively employed a “thought experiment” using captive mice to demonstrate the point. True: mice are not humans, but I’ll get to objections later. Holding daily food input steady results in a total mouse population fluctuating around a stable value. Providing daily increases of food (so that supply always exceeds demand) results in exponential population increase as long as suitable space avails and the regimen is maintained. Slowly decreasing daily food supply will reduce population, smoothy.

Food is therefore a perfectly effective “knob” for controlling the mouse population: none better. Food availability is a key mechanism in ecology too, for arriving at balanced populations. This knob will work on any animal or plant or fungus or microbe. Humans are among the animals of which we speak (hold the “yes, but…” for a bit longer).

Feedback

The case of increasing daily food sets up positive feedback. More mouths: then more food. More food: then more mouths. The cycle continues as population swells. Exponential, runaway growth is the hallmark of positive feedback. The enormous human population surge could not have happened without a dominant dose of positive feedback. That’s how math do.

Negative feedback can take a number of forms: food depletion, predation, and disease being the most easily identified and common in ecological contexts. A dynamic equilibrium (fluctuation around a longer-term average) involves an approximate balance of positive and negative feedback. Equilibrium doesn’t mean none of them are present: they just act in opposition to each other, leading to partial or total cancellation.

In a “pioneer” stage, positive feedback dominates over the others: not enough population to exhaust food supplies or concentrate disease, for instance. A late-stage population still has the positive feedback mechanism as fully-engaged as ever, but it is offset by the now-more-prevalent negative feedback elements: all together at once—all contributing.

A Human Thought Experiment

To those who resist the notion that increasing food production also means increasing human population, consider this. In 1950, the global population stood at about 2.5 billion people. The Green Revolution was about to explode into global agriculture, substantially increasing crop yields on the back of profligate fossil fuel inputs (for fertilizer, mechanization, energy for irrigation, transport, processing, etc.). Let’s say this tsunami of energy and technology had not arrived on the agricultural scene, and that moreover a global edict (“magically” followed) held annual food production at the 1950 level thereafter.

Would we have 8 billion people today? Impossible. We would still have 2.5 billion, correct? In 1950, the world produced enough food for 2.5 billion people, so that same amount of annual food would sustain 2.5 billion people today…or perhaps 2 billion taller, heavier people; or 3 billion people with more equitable, modest distribution and less waste. But you get the point: hold the food supply steady and you essentially hold the population below some cap. Inarguable. Those additional 5.5 billion people were made possible by a technological wave of food increase.

A Little Bit Louder Now…

Around that same period, the Isley Brothers’ song Shout had this fun sequence of “A little bit louder now,” progressively escalating in volume. That’s what actually happened to food supply, year after year. It is little coincidence that the highest-ever rate of human population growth sits right atop the Green Revolution. Food made babies. What else would babies be made of? As long as “decisions” to grow more food each year manifested, the positive-feedback result was essentially guaranteed. It’s certainly how things played out.

But the story did not start in 1960. Oh no. What was that other revolution that initiated the manipulation of plants for a higher level of human food production? Oh, it’ll come to me in a minute.

In the several hundred thousand years prior to agriculture, human population very slowly crept up, at a rate of about 0.0035% per year. Beginning about 10,000 years ago, the rate abruptly jumped an order-of magnitude, reducing doubling-time from the previous 20,000 years to 2,000 years—and monotonically decreasing thereafter as techniques improved (another case in point). By the 1960s, we grew at roughly 2% per year for a doubling-time around 35 years.

The volume knob (for food) was turned up a little bit louder each year, and human population rose along with it.

The Causality Question

Okay, okay. Push-back against the food-makes-babies formulation does not tend to refute the fact that increased food production went hand-in-hand with population increase. After all, babies are made from food. The argument centers on which drove the other. Sure: population increase requires food increase, but the reverse is not strictly true in pure (i.e., decontextualized) logical terms: an increase in food does not require population to increase. Surplus food could theoretically accumulate on the shelf, go to waste, be used for art projects, fuel food fights, etc. It seems perfectly plausible that food increases were always in response to population increase.

This is tangled territory, ill-suited for mental models. First statement: even if the imagined intent was more food in reaction to population increase, it’s quite possible that a misapprehension of the situation hid the causal nature of the positive feedback, so that more food actually preceded demand. In any case, we remained firmly in the exponential loop.

Second statement: let’s say people in the past didn’t get their act together fast enough and let several years or decades slid by before mounting an increase in production. Surely, procrastination is not a new human trait. The only way to keep population increasing (more mouths to feed) in this circumstance is for people to be progressively hungrier, with decreasing energy/stamina. That’s a hard place from which to mount a labor-intensive uptick. This argument—as any other—is not by itself conclusive, but the essential point is that nature offers no financing: to make a baby, food is demanded up front, which biophysically biases the situation for food coming first. Starvation conditions do not tend to produce baby booms that later require food production to increase.

Third statement: uncertainty and prudence tend to result in conservative over-production of food. Planning for surplus yield acts as insurance against all kinds of uncontrollable events. Lots of things can go wrong: low rainfall; a sweltering summer; a too-cloudy growing season; floods; insect waves; rodents finding stores; raids on your food supply by neighboring humans; the list goes on. A safe practice is to produce more than you believe you’ll need, as a matter of policy. In this case, surplus is not in reaction to population growth, but sure as hell enables it. It’s another substantial bias tilted toward a food-first causality.

Fourth statement: imperfect distribution means that even if enough total food is produced annually, some humans still go hungry and starve to death. In the modern era, the “humane” response has always been to seek increased food production—intending to fix the problem once and for all. As long as this is the (collective; automatic) decision, we stay firmly in the grip of the positive feedback loop. Increased food production in a global distribution system means even those who are not starving (but are not necessarily affluent) have greater access to food, which is where population growth tends to be highest. The phenomenon is also much more fine-grained than the whole-country level. A country hosting a starving subset of their population receives food imports and experiences population growth, but not necessarily dominated by the starving segment. The food going to the country stays in the country—some going to starving bellies and others going to well-enough-nourished bellies, some of which are “with child.” Being a global phenomenon, increased food also finds its way into countries that do not have significant starvation, but still express high fertility rates: food increase means more to go around. Many channels operate in parallel, even if our brains tend to tune in to only one at a time.

Fifth statement: aside from plague years, the experimental results are compelling: global population has increased for 10,000 years running—still to this day, for now. Meanwhile, we have never deliberately turned the global food production knob to anything other than “more” each year. If we haven’t, then could we, voluntarily? If we can’t, in practice, can we really claim to be in control—more than just notionally or aspirationally?

Some Data

Before getting into the legitimate confounders to the food-makes-babies recipe, I would like to share a peek I had into the situation, by using data from the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations (UN), which provides extensive datasets (here and here) on food production, imports, exports, nourishment levels, and lots more. I also utilize the UN’s demographic data in the form of the WPP (2022). An appendix at the end of this post provides more detail on my nerd methods.

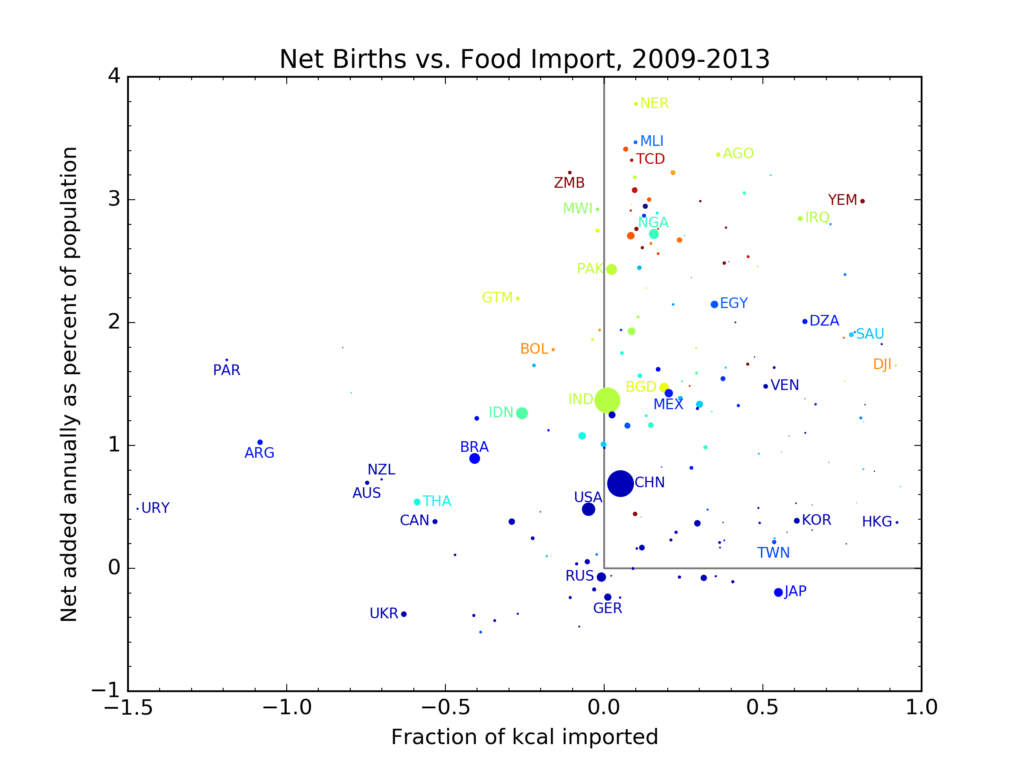

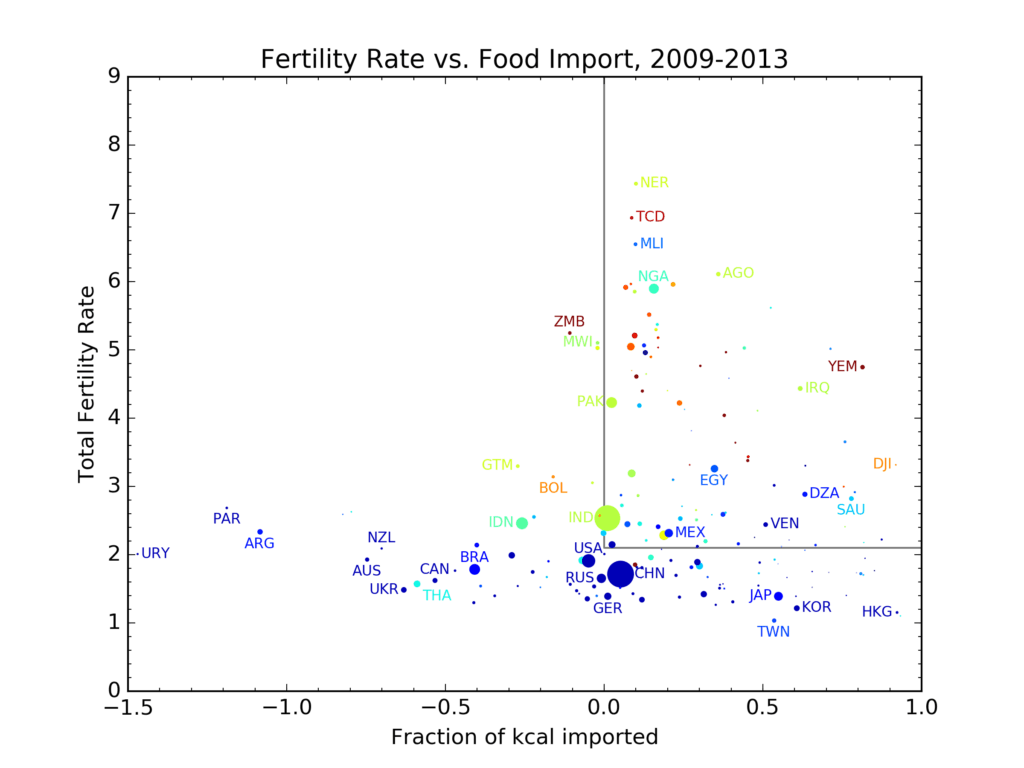

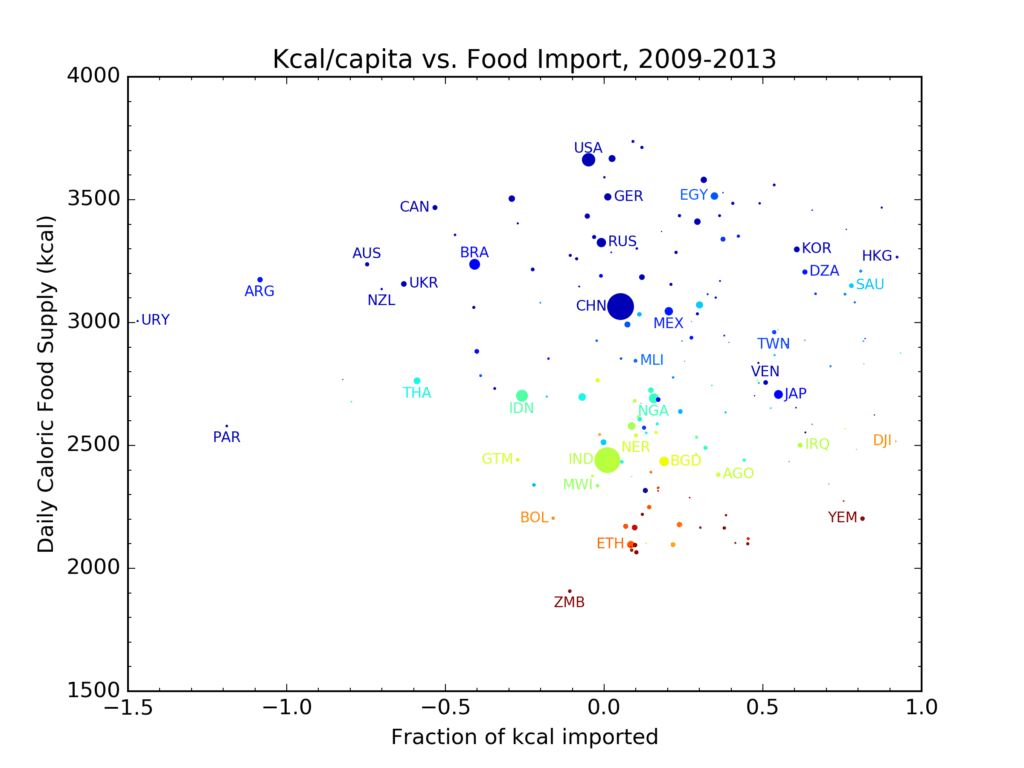

Below are two plots, each averaging the five-year period from 2009–2013 inclusive (latest period in the dataset I used). The first looks at births minus deaths in each country, divided by population and expressed as percent. By counting births and deaths, migration in or out is neutralized. The second has Total Fertility Rate (average number of live child-births per woman for the period in question, where 2.1 is the nominal replacement rate for modern societies). Both are plotted against caloric food import fraction, where each dot represents a country—its area sized by population, and colored according to fraction under-nourished (blue is well-nourished and red is under-nourished).

The different appearance of the plots is mainly a reflection of demographic inertia. TFR is a more reliable “now” measure, while higher net birth rates carry an echo of TFR a few decades ago when the current child-bearing population came into being. In other words, demographic bulges created in the past have worked their way to child-bearing years to keep the absolute number of births high. Both are valid captures in their own ways.

For each, I outline a box in the upper right in which net food importers are making babies. What this says is that population growth is largely in countries living beyond their local production means, requiring imports to fuel their growth. Overproduction in more affluent countries therefore supports population increase in countries of lower domestic food capacity. Below replacement-level TFR, import fraction seems basically random. Above replacement, the situation is heavily skewed toward food importers. One might say that this is the domain in which negative feedback has not yet overpowered the main positive feedback effect of food making babies (which has been the dominant story of the ages).

In Necker Cube fashion, the same plots support the opposite position: food excess (exporters) have low population growth (food makes not babies). The situation will never be settled if focusing on only one or the other aspect, as both are simultaneously true in a heterogeneous context—also complicated by a balance that shifts over time. Exceptions abound, but the net effect has been clear: the population growth manifesting today is largely supported by food importation. I’m not attempting to make a judgment here as to that practice so much as pointing out the biophysical underpinnings—as supported by data.

Real Grounds for Objection

In aggregate, then, I think we all agree that no food increases would mean a cessation of population growth. The hangup is that continued food increase need not translate to population growth, in theory. Except it always has, globally. But it doesn’t have to, and doesn’t do so in all locations—just in global aggregate throughout history.

Two related phenomena provide legitimate and powerful reasons to doubt the formula’s universality. First, affluent countries have the greatest access to food, yet show the lowest population growth rates (top plot)—lately even negative for some few. That’s real, and counter to the formula.

Secondly, total fertility rate (lower plot) is now at sub-replacement levels for countries hosting over two-thirds of global population, and these countries tend to be OECD (affluent). That’s also real. The sense this carries is that “civilized” countries have “arrived,” are in control, have defeated the “animal” feedback, and serve as a template to which others ought aspire.

Any theory needs to then account for the historical connection as well as recent exceptions, which is essentially impossible in a single-formula model in the context of a world teetering on a massive modernity-busting transition. Lots of past truths are about to be up-ended.

Nothing is Forever

Positive feedback never carries on forever, or the universe would break. Some influence (or many simultaneous influences) act to counter runaway growth at some stage. Having done so, the positive feedback contribution is not null-and-void. It doesn’t vanish from the equation: it’s just counterbalanced or overpowered by negative feedback. It’s more fair to say: food makes babies—historically—but only to a point. Food surplus made more babies for 10,000 years (and continues today), but not universally, and not forever.

In the current context of late-stage modernity, children become a costly affair in affluent societies. No number of all-you-can-eat buffets will offset the crippling cost of raising and educating children in a competitive market (obesity is also not the biggest turn-on). Adding to this is a sense among the younger-than-me generations (where babies originate) that prosperity peaked with the Boomers, that existential threats loom on all sides, and that the dream of the 1950s rings hollow today. Fertility rate is plummeting globally as the system that has been thumping along for 10,000 years is cracking up. The positive feedback is finally becoming overwhelmed, and is very unlikely to be exactly offset by the pile of negative feedback influences—more likely trampled by them. It appears we’re heading for a major population haircut, even if by “benign” demographic adjustment. But again, just because the historically dominant positive feedback mechanism is becoming overwhelmed is not the same as being invalid, or plain wrong. The context is changing, and I would say not by the exercise of control.

Speaking of context, the emerging fertility decline was not on the radar when Daniel Quinn kept hammering the point that continuing an annual increase in food production was a form of insanity: doing the same thing for 10,000 years in a row and expecting a different result. I have to say that I can’t see how he was incorrect. Had we stopped annual food increases at any point along the way, it is very clear that population could not continue to soar in some sort of biophysical detachment. That was his whole drive for returning to the subject: stop the insanity of food increases and the insanity of population increases will necessarily stop—because food, indeed, makes babies. Not wrong, but a complete political dead-end.

Reactions to the Knob

And to that point… Since Taker culture is obsessed with control of the planet, wouldn’t the ultimate control fantasy be to dial annual food production in such a way as to control human population? We know it to be effective. We also know that food production has only ever increased (minor, uncontrolled hiccups aside), while global population has only ever increased (again with the rare hiccup).

Let me be clear that I’m not proposing food curtailment as the right solution: attempts at (illusory) control are always going to go sideways, have more unintended consequences than intended consequences, and invariably hurt those who are not jerking at the levers of (partial) control. I just find it odd that those who cite our superior control as a basis for rejecting the animal-adjacent food-makes-babies formulation do not tend to advocate actual control.

This, I believe is the crux of why I am drawn to this “fight.” What can we learn about fundamental drivers motivating push-back against the biophysical formula? So, I ask you to consult your own feelings on the matter, in a thought experiment, to get at the core nerve the subject touches (if it even does, for you).

- What objections arise to the proposal of capping global annual food production?

- Does it seem cruel?

- Does it seem wrong to control people?

- Does it seem wrong to impose limits on humans?

- Should humans get whatever they want?

- Are limits evil, when applied to humans?

- Is the only way to be “fully human” to live outside of biophysical/ecological restrictions?

I’ll just say that some of these attitudes have disastrous consequences (witness modernity). Now, consider what these objections might translate to.

- Does this mean, in effect, that we will never voluntarily reduce or deprive humans of food?

- Are we therefore effectively powerless to the food-makes-babies phenomenon?

- Do we really have control, or is it more imagined/theoretical/aspirational?

- Is it more the case that other unbidden factors assert/manifest before the cycle is broken?

- Should it be: food will make babies until other factors beyond our control intervene?

To what extent, then, is our sense of control largely illusory? Who is it that planned the meta-crisis; 8 billion people; the future population plunge; initiation of a sixth mass extinction? It seems to me we got swept up in the currents, now imperiling the world. Along the way, a lot of food made a lot of babies—packing the stadium for the great spectacle of collapse under the weight of the assembled crowd.

Appendix: Procedure

For the nerd-curious: I used the FAO Food Balance data (available here) as well as the UN WPP data from 2022, and the FAO food security data here.

FAO changed their format after 2013 for Food Balance, and because I wanted the ability to explore a longer time interval, I went with the 1961–2013 dataset. This dataset is a spreadsheet 238,419 lines long. For each of the countries (and pooled regions), a variety of fields are provided to track food at different levels of aggregation (total food; animal vs. vegetal; about 18 sub-groupings; and then roughly 50 fine-scale designations). For instance, wheat and associated products are at the fine scale, belonging to the cereals group, which itself is in vegetals, and contributes to the total. Import/export data only becomes available at the group (e.g., cereal) level, and that’s where I worked.

In each category, total domestic supply is computed as domestic production plus imports minus exports plus anything that came from stock (which is negative if being cached). Of this supply, some is used for animal feed, some may be used for seed, some is lost, some is used in processing, and there’s even an “other” category (decorative macaroni art?). What’s left is called “food.” This quantity is also provided in translated form as kilograms per capita, and then kilocalories (kcal) per capita per day (and further broken into protein and fat content).

So, for all the categories, I compare the total net imports (negative if exports exceed imports) to total domestic supply (in mass terms) to compute the aggregate fraction of imported (exported) food energy for that group. To compare apples to beefsteak, I express each group’s imports in terms of kilocalories (multiplying by import fraction for that group to track imported food energy) in order to be able to add up across all groups.

A careful eye might notice that the plots showing fractional food import look like they are weighted (considering population, also) toward imports. This can’t be right! All imports come from exports somewhere in the world, so the population-weighted balance should be neutral. The reason it’s not is subtle. Because I am using each country’s fractional import/export based on caloric content, but not all countries operate on the same caloric basis (variation in kcal per capita), and exporters tend to enjoy higher kcal per capita, the result is skewed. In effect, the importers utilize the exports more frugally, so that a larger import fraction among light-eaters is offset by a correspondingly smaller export fractions in high-calorie countries. Anyway, I checked that absolute imports balance exports to my satisfaction.

The bias in question can be seen in the plot above: exporters (left of zero) have higher-than-average caloric supply, and importers trend lower. This skew offsets the imbalance in the other plots to make it all come out right. Note that the color scheme for nutrition levels track per-capita caloric supply relatively well (blue on top; red on bottom). Note also that not all supply is eaten, given (sometimes substantial) food waste.

Late Addition

A comment appeared on 2025.06.22 pointing to a highly relevant 2001 paper by Hopfenberg and Pimentel (I know of Pimentel’s work on energy inputs to agriculture). In addition to loads of pointers to related academic work, this paper refers to Daniel Quinn’s writings on the topic and also points to a few resources such as the extensive Q&A on the ishmael.org site. Specifically, questions 83, 169, and 208 were cited (on vegetarianism, hunger as a problem, and sustaining vs. expanding food). More generally, one might look at tags relating to population control, vegetarianism, and agriculture within the Q&A resource. Also cited was a Quinn speech called Reaching for the Future with All Three Hands.

Views: 2453

In Jared Diamond’s book “Guns, Germs, and Steel”, one of his main points or maybe the main point is that food availability is the key to understanding the “cargo” difference between Europeans and the indigenous populations they encountered in their expansion into the New World in the 15th and 16th centuries. I think this jibes well with your analysis here.

Tom, I'm glad you did a full post on this subject. This was one of the many ideas that blew my mind when I read Ishmael. For the first time in my life, someone explained the persistent claim that only $X millions could solve world hunger, with X not being some insurmountable amount of money, and yet we don't solve it. It's such an interesting paradox.

It also explains why everyone's favorite ideal goal of solving world hunger persists.

What will be fascinating is how the story upends over the coming decades. The TFR plot shows the degree to which the collection of negative feedback influences has overshot: countries didn't coast to replacement, but plummeted below. That's going to leave a mark. The ensuing economic chaos will also disrupt all those exports, so that import-dependent centers of population growth will not have the scaffolding to persist in today's manner. A whole lot is about to change, out of our control (as always), offering yet another "teaching moment" about our hubristic follies.

This explains why, even though we are growing more food than ever, hundreds of millions of people are still malnourished. We are soon gong to reach a point where the food supply cannot grow anymore.

https://insight.cumbria.ac.uk/id/eprint/6927/1/Bendell_BeyondFedUp.pdf

Hopefully, global population starts declining before then.

Very good synopsis. It's a very interesting debate. I'm still not wholly convinced on a causal relationship, although I've yet to hear a better case! I'm probably more intrigued by the cause of the increase in food production that either caused or allowed the population increase. The rise of agriculture, created the various abstractions that required a pursuit of growth (the birth of our system, I guess). That pursuit of growth includes extraction of all resources, including food. It could also be argued (because it's true!) that pursuit of economic growth requires growth in population. Thus, is it the system that is the cause of both population and food growth? Could we plot energy consumption against population in the same way you have done with food and return the same conclusion? Does TFR align with GDP?

I'm also intrigued by quality of food. Not all calories are equal. Could nutrition be a better driver of population than raw calorie? Difficult to guage I guess, but could soil nutrient deficiency in long-time industrial agriculture countries explain the drop in TFR? Or would it just be a negative feedback?

I have to admit, I'm comfortable with the more food = more people idea. It seems like a neat natural law, regardless of what causes the increase in food. The bit I struggled with more in Ishmael was the idea that famines were caused by food shortages. Whilst it is true, to a degree, it ignored the actual causes of the famine, which were usually war, or tyranny, and their associated displacement. The famine in Gaza, or Sudan, just now couldn't really be laid at the door of lack of food in the first instance. I'd also suggest that there has never been a net increase – globally – in food to assuage a famine. I didn't think the example really held, nor was it required in the making of the argument. I can imagine that example unnecessarily gave people a reason to put down the book (or be offended by it perhaps).

For me, the point about famine was that by having large numbers of people dependent on an "artificial" system to be fed opened up lots of ways that food supply could be disrupted, resulting in mass starvation. Whether crop failures (too dependent on a vulnerable monoculture) or politically-driven breakdowns, these are post-agricultural "inventions" that did not operate when everyone sourced their food on their own terms. Droughts happened, but by-and-large, populations never got a chance to exceed local carrying capacity until agriculture permitted this vulnerable and fragile state, easily disrupted.

Sometimes, this vulnerable and fragile state is used as a weapon. Examples include the Siege of Leningrad and the ongoing situation in Gaza. It is much harder use starvation as a weapon against hunter gatherers, although the US tried to do that to its indigenous people by exterminating the bison.

Another thing you might conside is the profit motive.

Producers of food, whether individual or corporate, have some motivation to profit from their endeavors. Each producer seeks to increase profit, and the primary way to increase profit is to increase sales. To increase sales you must increase production. Even in a static market, producers are likely to increase production.

In a static market, increased production is likely to depress prices, as each producer attempts to make his/her produce more attractive to the limited market: product availability increases, price decreases. The market looks at this and concludes that, given how cheap produce is, it can afford to stop being static.

Et voila!

There's no energy like metabolic energy.

I think that the food makes babies argument is pretty solid and tethered to biophysical and energy realities. In terms of positive feedbacks being trampled by negative feedbacks… Yes. And while there is no singular story among a whole spectrum of tragedies, I keep coming back to food in my own thoughts as something fundamental that can make us and break us, and expect its absence to play a substantial role in said trampling feedbacks.

What is the current state of our agricultural system and what cracks are already appearing within it for those paying attention? I'll list a few. – We're losing 3 trillion tons of ice from mountain glaciers every decade that some ~3 billion people rely on. We feed ~4 billion people using methane via the Haber Bosch process while natural gas reserves are being exponentially depleted. Quickly depleting fossil fuels underpin every other aspect of modern agriculture as well, presenting a clear road-closed sign ahead. Insects are disappearing at ~2% per year, pollinators are being lost. We're depleting ancient aquifers faster than they can recharge and are majorly stressing thousands of watersheds. Land is being degraded and 24 billion tons of top soil lost every year. The ocean is rising in non-linear fashion as paleoclimate data from the Eemian and James Hansen's work indicate that the Western Antarctic ice sheet goes in the ocean within a century at the temperatures that we are currently experiencing, causing 15 feet of ocean rise, inundating and salinating fertile river deltas and devastating low lying coastal regions and their populations. GISS models have the AMOC likely shutting down mid century throwing both northern and southern hemisphere weather patterns out of whack, creating agricultural chaos, and simultaneously devastating fisheries (on top of losing corals), resulting in less protein available from the ocean. Climate change brings heat waves, droughts, extreme weather, unpredictable weather patterns, moving jet streams, and new highs pushing plants outside of their adaptive ranges (while CO2 fertilization is a small contra, more mass but less nutrition). Other accumulating pollution such as micro plastics are already cutting our yields down some 10%-20% as they disrupt photosynthesis and continue to accrue. The Amazon rainforest is weakening toward savannah and my understanding is some 35%-50% of all rainfall in North America is the result of the Amazon's hydrologic pump. Add on top of this that in American society (emblematic of modernity culture) some 99% of workers are in the tertiary economy, they're accountants, lawyers, telecommunication specialists, and astrophysicists, but nobody knows how to sustainably grow their own potatoes. – We're a population lacking skills, knowledge, experience, community, infrastructure, tooling, physicality, etc. to do the physically-taxing labor of meeting our own caloric needs. The 1% who are growing all the food are primarily using unsustainable giant fossil fuel machines and are therefore similarly unskilled at producing food in sustainable ways. In addition, high population density cities exist without a possibility of sustaining themselves as they rely on massive external energy and material inputs with little unpaved-over fertile land remaining for calorie production. And as you've mentioned before, we are down to 2.5kg of wild mammal mass per human, thus the hunter-gatherer bounty available to our ancestors is no longer present today.

– No doubt there are more points that could be raised, but we seem to have gone all in on an absolutely insane and unsustainable way of meeting our caloric requirements as a species without any clear off-ramp. Is there any way that this doesn't end tragically?

@Alex

That all sounds like a pretty good summary of where we are at.

When I first came across the food baby connection in Ishmael, it seemed matter of fact to me, so I do struggle to understand what the fuss is all about. Your articulation and data based approach is quite comprehensive, builds an even stronger case and is a great synopsis on the topic.

A slight tangent, (but it was brought up in the post) – I understand the universe is expanding, at an ever faster rate which looks like positive feedback. The universe will probably ‘break’ at some stage either because of this, or it will ‘break’ because negative feedback takes over – the big crunch. Stars also break eventually in a positive feedback fashion.

(If I may ask (in jest at least), if food makes babies, then what makes a universe?)

Anyhow, for now we have bigger concerns, namely the big crunch here on earth.

Paul Ehrlich (population bomb) is the famous 'victim' of green revolution. Demographer Dr. S. Chandrasekhar was another. As India's health minister in the sixties he advocated birth control. Western media ridiculed him that his partially successful plans (surgery and abortion) were impractical. Later came the green revolution and he was completely forgotten. He spent his later life in La Jolla writing well-researched books. Indian government's policy of 'Two per family' then 'One family one offspring' was abandoned.

I've read all the Quinn books, gleefully, but did have trouble with the food equals babies, living in Australia where the NFR is low and there is plenty of food (and fossil fuels to export!). So thanks for that explanation. Makes a lot of sense. Will be interesting to see what happens over the next decade – if I am still around.

You make a good case for food creating babies. What doesn't create babies (or not many) is contraception. And whilst you've previously pointed out that older people (octogenarians?) were not too rare in primitive communities, they are much less rare these days. So food also keeps more people alive, as does medicine. There are many factors in overshoot, though, definitely, food availability is crucial.

Tom, the bit about the population without Haber-Bosch nitrogen (2.5 billion) misses an important point – that this calculation is based on the current animal dominated food supply where a large proportion (probably most) of the synthetic nitrogen is used very inefficiently by feeding animals to then be eaten by humans. Take the animals out of the equation then there is much more food available.

Take the animal out of the equation?

That’s advocating for the extinction of that animal species. Us humans are relentless and destroy things we don’t value.

Take the haber/bosch process out of the system to begin living inside our limits.

Take the human mismanagement out of the system and support the survival of the more than human world

I highly recommend viewing the most recent youtube video by Robert Sapolsky, "Father, Offspring Interviews #66" ( https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zybIdcDp1JE ), in which Sapolsky discusses the genetic changes that have occurred as a result of the practice of agriculture.

I watched the relevant segment (first third), and found it to be a good account. Much of what he says matches well recent anthropological work I've been reading. I had not (at least memorably) encountered the connection of diabetes and auto-immune diseases to agriculture. Not mentioned were the superior bone density and dental health of pre-agriculturalists. A whole raft of consequences for living out of our evolutionary context…

Very interesting. I was particularly interested to hear about the dopamine receptor DR4, some variants of which “are associated with novelty-seeking, impulsivity, sensation-seeking and ADHD” (13:50 onwards). Robert states that there was very strong selective pressure against these variants when intensive agriculture appeared on the scene. I found this fascinating because my general sense (which is worth close to nothing, I admit!) was that these types of behaviours are on the rise and that there may be a link between this rise and increased social media use/screen time. I have also tended to view these behaviours as just another “bad” development associated with us heading down the “Modernity pathway”. But, yet again, it seems I could turn out to be completely wrong… though I am not sure either way now 🙂 For example: in a new forthcoming book, anthropologist Kate Fox argues “that we are using Digital Age technology to recreate Stone Age social dynamics. Smartphones, social media, cyber-dating, gaming, etc. are all part of our latest unconscious attempt to reproduce the social essence of the environment in which we evolved, the Palaeolithic. We are not suddenly becoming addicted to gadgets and screens. The internet is not turning us into shallow, selfish narcissists. What we are doing is a form of 'counteractive niche construction' – using technology to try to recreate our evolutionary comfort zone, the kind of social world our brains are wired for. This is nothing new; we've been trying for 10,000 years, since the Neolithic, with partial and varied success. This time, we have better tools. Could this be the dawn of the Palaeodigital?“ (https://www.hachette.com.au/kate-fox/the-new-tribalism)

Ah, my comment above is probably another case of my silly limited brain trying to make sense of something that is a lot more complex than I give it credit for… by, once again, oversimplifying it and making way too grand general statements about it! (Receptor biology is obviously exceedingly complex, to begin with!)

I do certainly feel that social media seems to aid in keeping a lot of people imprisoned in Modernity, but maybe that is just the algorithms and the way it gets exploited by businesses and right wing nut jobs that I am hung up on. There does also seem to be a strong addictive aspect to it that makes some/many people quite miserable, me included. But maybe the keen uptake of social media across the word is also revealing a genuine yearning for something different than what Modernity generally offers, something that our brains genuinely want in a “healthy” kind of way. The idea that social media is facilitating the emergence of “new tribalism” is interesting. Social media often gets a bad wrap in mainstream media because it is said to be splitting us into polarised, warring tribes – the “worst” ones being the “extreme left” and the “extreme right”. A threat to Modernity! But I guess there are plenty of other little tribes of a “good” type being formed at the same time, and perhaps the major splintering we are witnessing might actually be just what is needed right now??

It must be said, of course, that these tribes consist of people that may never meet face-to-face and are generally physically separated by large distances. So the tribes lack the proper ecological context. It is tribalism in a digital world, not the real one. It is a tribalism dependent on technology, tribalism that is therefore currently contained (imprisoned?) within Modernity. But perhaps it may find a way out, or help Modernity to eventually transform into something “better”???

Great post, thank you Tom. I think the hypothesis is very plausible, but not easy to pin down. It would be also interesting to look at how food production and population growth unfolded in time. I assume one could find more correlations (and perhaps time lags too) that could further support it (in practice I suppose data availability becomes a problem pre-1970..).

One thing one notices at a macro level is how the population vs. income growth trends in 'old' industrialized countries compare to those in the rest of the world. There are some basic similarities, but also some differences. In (many/most) low-income countries today, the fold-change in population compared to their 'pre-explosion' baseline was/has been not only larger, but this growth happened much faster — basically all after 1950. European countries often took about one-two centuries to double or triple their population (and then slowed down), whereas many parts of Africa experienced the same (relative) growth within just 30-50 years. I assume this has to be due to the rapid increase in agricultural productivity (not necessarily in *those* countries) after WWII; along with improvements in medical technology (mainly vaccines?). I'd speculate that previously (eg. 19th century Europe/North Americal) the increase in food production probably moved together with a generally lower rate of economic growth, acting as a limiting factor. (Of course there would be so many causal factors here..)

ps. recently did a surface-level analysis of these trends, just to see macro-level differences, though it’s far from a causal analysis: mbkoltai.github.io/demogr-econ-growth-rich-poor/

One thing that I notice about a competitive nation-state system is that it is more maximum power principle than either global governance (which would have its own faults), or the absence of such a system. If we take Odum's elaboration of Lotka's principle, 'system designs develop and prevail that maximize power intake, energy transformation, and those uses that reinforce production and efficiency', a competitive system that engages in arms races and wars is intaking more power, transforming more energy and emphasizing production and efficiency more than its (hypothetical) counterparts. (A global government wouldn't need to worry about arms races having a monopoly on violence).

Since militaries are not societally disconnected entities but have their success also tied in with their host-nation's economies, industrial bandwidth, infrastructure, and even population size, a military's success is correlated both to embodied energy and velocity of energy consumption. Military competition is often credited with being the catalyst for 'great technological advancements', but to the more discerning eye, the result is more like an energy drawdown accelerant. All the economic and industrial bandwidth ramped up to fight WW2 remained after peace was declared, and was then retrofitted to civilian purposes (no going back). There was a huge explosion of energy use that persisted after WW2, maintained via the advent of modern consumption culture.

Food works similarly in that there is an element of arms race, food = babies = future troops. Having more embodied energy in the form of troops than an adversarial group can confer substantial competitive military advantage, particularly in antiquity when hand to hand combat dominated.

Food at it's heart is a particular iteration of energy, bankable calories. Could it be that: A) All human populations above Dunbar numbers become unwieldy because faulty human fabrications must be imposed to 'manage' the complexity that corresponds to larger groups (governments, laws, economies, etc. become necessary)? B) We are lousy as a species at managing surplus energy in sensible ways because we are disposed to prioritize human interests, while aggregate human behaviors tend to be chaotic and mostly mindless but possess concentrated potency for destructive capabilities and negative environmental impacts?

George Carlin had a quote "An individual is a universe, but groups are stupid." Following that logic, perhaps we could argue that the bigger the group, the stupider it becomes. – One of the less contemplated facets of having a ballooned population. Our aggregate behavior as a species is stupider than ever, but we have nuclear capabilities and biosphere destroying potential.

Another fascinating post!

"[A}ttempts at (illusory) control are always going to go sideways, have more unintended consequences than intended consequences, and invariably hurt those who are not jerking at the levers of (partial) control."

There's truth in that. Like flying an airplane: there are control surfaces on the wings and tail that you can move from the cockpit. Under the carefully-managed conditions of normal flight, it can seem as if the pilot's control of the aircraft is nearly total. But step outside that envelope—say a dive, or a spin—and the limitations of control quickly become manifest.

It's easy to solve the ills of the world with a sweeping wave of the arm and fantastical prescriptions like, "Humans will evolve to a new level of consciousness, stop being so selfish, and all nations will work together . . ."

But the conversation only becomes really interesting when one takes very seriously the question, "What realistically can be done?" Politics and government is "the art of the possible," as Kaiser Wilhelm said.

Here's a very short clip of Prof. David Betz speculating on limits of government control in the U.K., and what actions might be taken. Unrelated issue, and I don't necessarily endorse his conclusions, but it makes one think

https://youtu.be/Hf0VKszbn7Q&t=2646

(Watch 3 min from 44:05)

I can absolutely accept the reasonability of there being a certain level of population stably supported by a certain food supply, but the exact mechanism of decrease has me pondering.

Is it the case that when the food supply is restricted (e.g. a famine arrives) it's not that the birth rate per capita decreases much or at all (creatures 'choosing' to have fewer offspring, which seems somehow relatively unlikely, to me), but that the infant mortality rate increases (due to malnutrition, disease, ill-health etc), with the consequence that the number surviving to fertility (and thus produce the next generation of offspring) decreases? After a generation or two the population will have decreased to a once-again safely-supportable level, and infant mortality will have come down. (The inverse will be the case if the food supply increases).

Is it also the case that the fact that human population increases as a consequence of more food being produced with the aim of preventing famine is effectively the result of 'imperfect distribution' and greed for excess?

Good questions. I found this article titled "The effects of food shortage on human reproduction" https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8414274/ which does suggest that fertility itself is reduced by lower food availability. I also came across a number of references to fertility declines due to malnutrition (sometimes from resulting hormonal imbalance or other physiological deficits). But I continue to be surprised at how hard it is to find data on the subject. It seems like experiments with mice like the ones Daniel Quinn described would have been done many times by now (not particularly difficult), but seemingly not. Is it taboo?

Not sure if this is relevant, since it's not about food availability or fertility per se – I've known quite a few women with disordered eating/self-starvation issues, which resulted in them having irregular or absent menstrual cycles, sometimes for many months (in the case of one untreated anorexic, them stopping altogether for years). Amenorrhea also can result from periods of prolonged intense stress (which I'd think famine could qualify as causing). So that's my anecdotal theory that starving people don't make babies because literally, they can't! It makes sense to me – your body doesn't know why the hunger cues aren't being satisfied, but that it indicates reduced food availability and thus, it's probably not a good time to even try to bring a baby into the world.

In any case, agreed that it does seem odd that there's so little actual research and that for, whatever reason, it's an off-limits topic…

You are focusing on the wrong energy source. All species expand to fill their available energy niche. In the case of humans, after the industrial revolution we expanded, both in population and longevity, to consume our Fossil Fuel energy niche. Food production increases were simply a by-product, like vaccinations, water and sewage treatment, etc… to support consume the Fossil Fuel energy niche.

Now the fate we are facing is that the relative Energy Return on Energy Invested of Fossil Fuels is rapidly depleting to be on par with agrarian energy sources. See for example the terrible returns on tar-sands bitumen (5:1 at best, frequently 2:1). There will be massive shifts in technology and economy once Fossil Fuel powered vehicles are no longer as effectively efficient as beast of burden, at the scale of global averages.

No real disagreement here (see an older post called Finite Feeding Frenzy). Material from the Big Bang and previous stellar generations combined with gravity to make the sun, which made fossil fuel, which made food, which made babies. Plenty of people resist the last connection.

Also no mention of this topic is complete without referencing John B. Calhoun's Mouse Universe experiments.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_B._Calhoun

I'm surprised that this is contentious!

Anyone who has been through an undergrad ecology course has been exposed to this — the classic hare-lynx study is in the canon.

I guess the controversy comes from "human exceptionalism", the notion that we have "evolved" beyond our natural proclivities, that our social structures and big brains allow us to behave differently.

Not so fast! Since the advent of grain agriculture, we've had some ~7,000 years (minus a couple hundred) where the correlation (if not provable causation) of food to babies held true.

So what happened in the past two hundred years or so that strains the credibility of one of the major tenets of ecology?

I was also reminded of Calhoun's rat study, and am grateful that Aaron Sheldon saved me the trouble of looking up the link. In that case, the rats saturated the living space, and other factors took over. I've poured over Calhoun's later studies, and saw no clue as to why. But the rats stopped breeding, taking up alternate activities such as excessive grooming (just watch some popular culture to see that!) and organized fighting (I'm sure I don't have to point out the human parallel).

Alex hit on what I've long though explained the so-called "demographic transition": Howard Odum's (and Alfred Lotka's) "Maximum Power Principle" (MPP), that a system evolves to dissipate the maximum amount of power possible.

And what happened two hundred years ago, is that, for the first time in the history of life, we began exploiting an energy source that was not food. The age-old, Malthusian notion that "food (trophic energy) makes babies" got short-circuited by fossil sunlight energy.

Similar to Calhoun's rats, we humans now have most of our basic needs provided by something other than food, to the point that we no longer need to breed a slave labour force and retirement plan.

We are still prisoners of what Lotka proposed to be a 4th Law of Thermodynamics, if we expand that to include all energy that we mindlessly dissipate.

Might it turn out that "food makes babies" is not the underlying principle at all, but merely the most visible side-effect that "making babies" has always been our primary way of dissipating power?

If so, this does not bode well for the future.

As fossil sunlight goes into permanent, irrevocable decline, our need to dissipate power (which we share with sub-atomic particles and galaxy clusters, as elaborated by Gunderson's and Holling's "Panarchy") may once again be manifest through fecundity.

When we lose access to electrical water pumping, and the excess of government and industry no longer take care of us in our latter years, women may once again need to breed a slave labour force and retirement plan.

"But I didn't have children, thus everyone could choose to not have children."

This argument embodies one of our greatest failings: the inability to tell the difference between the individual and the aggregate.

Just as one cannot predict when an atom of a radioactive isotope will decompose, one cannot predict individual human actions. An atom of iodine-131 may decompose in milliseconds, the atom sitting right next to it may be stable for many months. Yet, in the aggregate, to many significant digits, half the atoms of I-131 will decompose in 8.0249 days.

Same for us humans. We exhibit tremendous individuality, which makes us blind to our aggregate conformity.

Please see https://www.researchgate.net/publication/226928770_Human_Population_Numbers_as_a_Function_of_Food_Supply

Fantastic find! I know of Pimentel's work in characterizing (fossil) energy inputs for various foods. I had never run across this, but it looks very promising in support of the basic thesis.

Reading the paper now, and it seems Quinn's writings played a motivational role:

"Our position is that population growth, the prime environmental problem affecting all ecological, biological, and non-living systems, is a function of increasing food production (Quinn, 1992, 1996, 1998a; Pimentel, 1966, 1996)."

It seems Farb also pointed this out in 1978…

One problem with the "Food makes babies" narrative: the last fifty years, which has seen birth rates in industrial nations plummet to below replacement level, without a corresponding reduction in food.

In Calhoun's famous rat/mouse studies, he found something similar, that as population approached a certain unquantifiable limit — fed by constant surplus trophic energy — fecundity levelled off, and then fell. (Besides all the food they could eat, his rodents had fossil-fuelled light and heat, albeit without cute kitten videos.)

I've come to go a step deeper, and view "food" a merely a special, but general, case of energy, which is power dissipated over time.

When an organism finds itself with an excess of non-trophic energy, it will switch from dissipating power by breeding, and replace it with dissipating power by driving 30 minutes to/from work, watching cute kitten videos, and using AI for their term papers. (Not to mention purchasing food that has ten times as much fossil sunlight energy as it supplies in trophic energy!)

Thus, the Maximum Power Principle (which Lotka tried to promote as the Fourth Law of Thermodynamics) trumps "food makes people".

It would be interesting to plot per-capita total energy use over time from all sources for all purposes, and see if the cross-over from food to non-food energy sources corresponds with declining birth rates. (Again, keeping in mind that most trophic energy is supplied by ten times as much fossil sunlight energy.)

If so, this does not bode well for the future. As fossil-sunlight goes into decline, most contraceptives (and cute kitten videos) may go away, and women may once again breed their slave labour force and retirement plan.

I think that MPP works in many cases including game theoretic human competition dynamics and is observed in evolution and ecology as energy gradients across ecosystems etc. It could be expressed as a conferred advantage of a plant with deeper roots or the largest ape in a troop becoming the alpha, and so forth, yet I am reticent to adopt it as the overarching principle, especially of ecology, because I sense that things are simply more complex than that. In the same way that 'survival of the fittest' is a factor but not the full story of evolution, there seem to be symbiosis and integration within ecosystems, and thus energy trade, between organism, in addition to competition over energy, and thus MPP may not paint the full picture.

Of course, food is energy, but it is also quite special stuff. You could take 500 gigajoules of energy to surface of Jupiter, but good luck producing food with it. Everything that we consume (with the exception of a few modern atrocities) was at one time a living organism, and thus food is also life and ecology, and requires certain favorable environmental attributes to procure.

Another issue that I take with MPP as elaborated is what it means for a system design to 'prevail'. Using more energy than an adversary could confer an advantage, but if that energy is finite and being depleted exponentially… If you won a knife fight on the Titanic right before it sunk and you froze to death in the icy waters, would you have 'prevailed'? (The insanity of a military industrial complex predicated on fossil energy).

Let's look at a quote from Lotka, Elements of Physical Biology, 1925: We have every reason to be optimistic; to believe that we shall

be found, ultimately, to have taken at the flood this great tide in

the affairs of men; and that we shall presently be carried on

the crest of the wave into a safer harbor. There we shall view

with even mind the exhaustion of the fuel that took us into port,

knowing that practically imperishable resources have in the mean while been unlocked, abundantly sufficient for all our journeys to the end of time. But whatever may be the ultimate course of events, the present is an eminently atypical epoch. Economically we are living on our capital; biologically we are changing radically the complexion of our share in the carbon cycle by throwing into the atmosphere, from coal fires and metallurgical furnaces, ten times as much carbon dioxide as in the natural biological process of breathing."

We have to credit him with being quite perceptive of both the rapidity of our biological and chemical changes to Earth's systems and the unsustainability of living off finite capital. Yet, the idea that a future of boundless energy was achievable, desirable, or safe I think is misguided. If we've done this much damage with 10% of Chicxulub's energy, how much would we do with 20%? (Probably roughly twice as much, regardless of energy source). Turning the Earth into a giant human amusement park was never an appropriate goal designed to 'prevail', on ecological and other grounds.

Well put: a valuable comment.

Please see ww.researchgate.net/publication/357430417_Human_population_activity_the_primary_factor_that_has_precipitated_a_climate_emergency_biodiversity_loss_and_environmental_pollution_on_our_watch

I'll be away until July 6, so please submit comments but be aware that I won't be able to approve/moderate until I return.