Almost as if done deliberately to demonstrate mental incapacity, I recently found myself making a connection that was staring me in the face for years but that I never recognized. Surely, scads more sit waiting in plain view, yet will never be smoked by me as long as I live.

In this case, several overt clues tried waving it in my face, but I remained oblivious. I feel like my former best-buddy cat who was always mesmerized by water, never tiring of watching it slosh, splash, and splatter. My wife and I once took the cat(s) on a reluctant car trip passing along the coast of northern California. The road came right up on the beach, and I stopped with the idea that I would show the ocean to him, which would surely captivate his attention and blow his mind. We were so close that the ocean and waves dumping on the beach were almost all that could be seen out the window. I held him up to take in the sight, but in his squirming state—questioning what new cruelty I was subjecting him to on top of this already-heinous and interminable car ride—he somehow managed to completely fail in ever noticing the ocean. But it was right there in front of him! You can lead a cat to water…

Oh—I should get to the point? A couple weeks back, the post on Spare Capacity mentioned the outsized detrimental impact written language has had. I know. Here I am still using it. But like my cat, I failed to notice what kept filling my field of vision.

Writing is Bad?

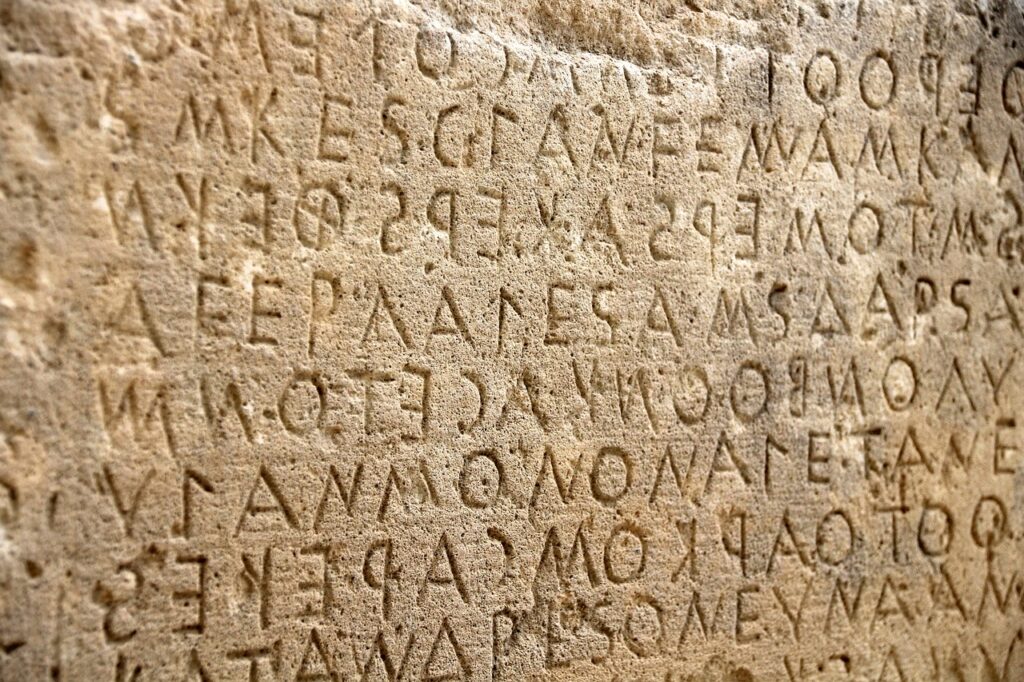

A brief synopsis of the premise is that written language is a central load-bearing pillar supporting modernity and by association a sixth mass extinction. Early-stage modernity relied quite heavily on writing to effect accounting, money, law, religious scripture, and complex political discourse. Science extensively rests on written documentation. On the heels of agriculture, written language elaborated the ecological dangers of this untested mode of planetary living—cementing concepts and practices in a formal and rigid manner.

The very aspect we celebrate most about writing is also what makes it dangerous: we lock in accumulated knowledge in a sort of external and more permanent “brain,” greatly amplifying our innate capacities, sweeping us out of our original ecological context, and putting us on unvetted evolutionary ground.

The central question becomes: would the sixth mass extinction now underway have been possible without writing? Okay, maybe it’s possible that agriculture alone without writing, money, science, or fossil fuels could have managed the sixth mass extinction in due time, but it’s also clear that writing made it extraordinarily more efficient and likely. Less clear is whether an agricultural way of life could have trundled along without ever developing writing. The only evidence we have suggests that one promptly follows the other.

Missed Opportunity: Earth Abides

Several impressionable and related recognitions had danced across my neurons previously, but without full effect. The first was in the sometimes hokey but still worthy piece of fiction from 1949 called Earth Abides, by George R. Stewart. Holy crap! It’s now been made into a TV series of six episodes. I’ll bet it’s terrible. Anyway, the main character, Ish, is a PhD student at (presumably) Berkeley when a devastating epidemic wiped out nearly all of humanity in very short order. It was Ish’s dream to rebuild modern society, banking on preservation of the now-sacred campus library containing basically all the knowledge needed to restart.

Ish was determined to educate the next generation of kids that came along (born post-epidemic), teaching them to read. They tolerated the lessons out of politeness and deference, but most of the kids really wanted nothing to do with it—as irrelevant as it was to daily life when so much more could be learned by hunting and gardening and foraging and observing. In the end, Ish’s ambitions were not satisfied, yet the kids grew up healthy, strong, and happy without written language.

The book made a big impression on me as a lesson that one generation’s sacred cows can be completely rejected by the next—especially in the face of major disruption. As modernity crumbles, I expect the pre-transition generations to cling and advocate for restoration of glories past, while the young will be more-than-justified in ignoring such backward-looking blubbering babble.

So, in this story, the role of written language (and its subsidence) was front-and-center, yet it never caused me to ask what role the advent of written language played in shaping the terminal predicament in which we now find ourselves ensnared.

Missed Opportunity: My Ishmael

In preparing an upcoming treatment of Daniel Quinn’s My Ishmael, I stumbled on something that I had failed to register in previous readings, characterizing written language as: “our culture’s powerful invention (after totalitarian agriculture and locking up the food).” How many other crucial insights fly right through my brain multiple times before catching on a neuron?

Missed Opportunity: Cunk

The Cunk on Earth series consistently tickles my funny bone. In clever/subtle ways, it really pokes fun at human supremacy, our mythologies, and our arrogance. It exemplifies the “genius of dumb.” As a (former) academic “expert,” I relish the talent that Diane Morgan exhibits in tripping up pundits, while still allowing them to come off as likable creatures.

Anyway, the Philomena Cunk character at one point asks a bushy-bearded academic showcasing a relic of early writing if he thought writing was legitimately a big deal, or just some flashy fad. Even that failed to engage my meat-brain in assessing just how important writing may have been in facilitating our drive toward a sixth mass extinction.

The overwhelmingly positive value of writing was beyond question, given my cultural context.

Missed Opportunity: River Tributary

For the post called Our Time on the River, I clearly put more than passing thought into all the various contributions to our present state on the raging river of modernity. The ride started with agriculture, promptly joined by tributaries of settlements, possessions, surplus, armed force, property rights, division of labor, patriarchy, hierarchy, classes, the state, and on and on. Yet one of the biggest developments of the era—written language—did not garner a mention.

Again, this is not because it lacked sufficient importance, but simply that I failed to appreciate that something so close to my heart might have such profoundly negative impacts in terms of accelerating our now-perilous river experience. And writing isn’t the only missing piece: money is another enormous influence inexplicably finding no place on my diagram.

Suitcases on the Slow Train of Thought

Given that I repeatedly missed opportunities to spot the obvious, it may be instructive to retrace the steps along the way that finally allowed it to click.

I was musing on the idea of spare capacity in our brains: that all our awareness in thought amounts to an extraordinarily slow and modest capability barely scratching the surface of all the real-time processing that goes on among neurons. The part that we directly experience is therefore the slimmest fragment of a much more elaborate complexity beyond our detection capabilities.

It was in considering the impossibility that we could pin down our experience of awareness (i.e., what we call consciousness) from first principles that led me to think about suitcases. That’s right: suitcases. For those of us living in houses, various rooms store furniture, clothing, food, vehicles, tools, etc. We also have a bit of “spare” storage in the form of suitcases, but typically this is a small fraction of the total, and usually kept empty.

Anyway, trying to fit a multi-layer process as complex and mysterious as our experience of consciousness into the spare capacity of our already-tiny meat-brains is asking far too much. As a member of a consumer-based culture, I somehow jumped to the mental image of trying to cram a shopping mall’s worth of clothing into a single suitcase. It ain’t gonna fit, no matter how hard you push.

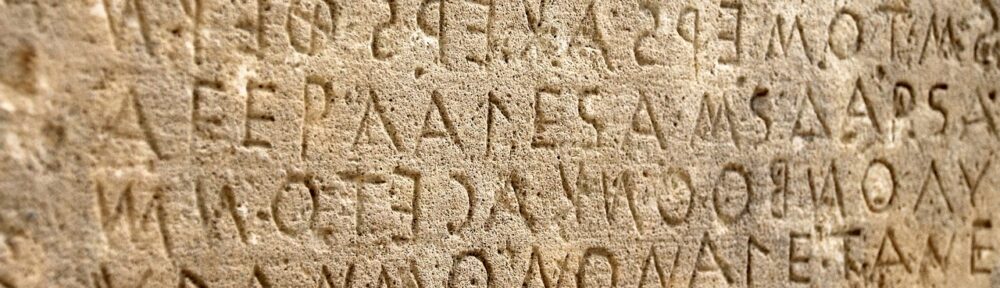

But here’s the trick we employ: we buy a lot of suitcases. We pack each one, label it, put it on a shelf, index it so we can connect it to others at leisure, and keep going. In this way, we accumulate a lot of “thinking” that doesn’t fit into our brain all at once. We call it writing.

By writing stuff down (or drawing diagrams or other forms of thought preservation), we offload useful/relevant thoughts into a safe place that can later be reloaded and connected to other stored pieces. It’s very clever and powerful. The technique leverages our spare capacity into something quite dramatically roomier.

Excusably Dumb

So anyway, I was a bit of a slow coach in recognizing written language as one of the major factors responsible for accelerating our path to modernity and giving us the power to wreck the world. All those suitcases come to no good, as proud as we might be of each one in isolation, or of the whole idea of knowledge preservation beyond oral tradition.

In my defense, we’re all (collectively) slow to recognize novel elements, especially when swimming against strong cultural currents. I mean, I’m not sure I had ever encountered anything but effusive praise for the development of writing. Look what it enables us to do! (Exactly, say the extinct—if they could.)

Yet the whole time, the dark side of written language was hiding in plain sight. The writing was on the wall.

Views: 3826

But come on, describing a phenomenon in language, no matter how rich it is, greatly simplifies it.

Another inconsistency of attributing noun words to processes. Gravity, wind, flash, light, these are all nouns. But what they describe is not. Another level is category words or generalizing words.

How many people have been killed because of a verbal dispute about democracy?

Another level is conclusions. How many times have we made an assessment of someone or something without getting to know them properly. And if this affects life/salary/family?

Yes, this does not apply to writing, but our language has also changed, along with the progress of modernity. Indigenous languages with oral tradition are much richer in verb concepts with very subtle contexts. Where one complex level is identification in language. There is nothing identical in the universe (well, almost nothing), everything has a unique manifestation. We easily identify everything.

John 1:1 In the beginning was the Word.

Excellent article. You explore the often overlooked negative effects of written language on modern society and the sixth mass extinction. Despite numerous references, including the novel “Earth Abides” and the series “Cunk on Earth,” you fail to see how writing enhances human abilities and accelerates ecological destruction. You use these examples to show how writing helps offload thoughts, enabling knowledge to grow beyond individual limits, but ultimately contributes to global problems.

Martin, I'm confused. Tom Murphy uses each work ('Ishmael', 'Cunk' etc.) to explain how written language facilitated the progression of humanity toward modernity and all that that entails for the planet. He critically assesses writing, i.e. "knowledge preservation beyond oral tradition". He then condemns it because of the technological and other sorts of progress that the written word enabled, much of which has resulted in irreplaceable use of finite natural resources. In the past, Tom didn't have this insight, but he clearly does now. Or maybe you're just writing a summary of Tom's post?

I cannot find anything to disagree with in any of your recent posts. But, but… the turn we are taking… are we giving up on the idea of a soft landing? It may be true that the moment writing enabled accumulation of knowledge the sixth mass extinction was set in motion, and the failure of the experiment represented by our little branch of the evolutionary tree was guaranteed. But what do we do with this information? I think that's the key question, and it's getting harder and harder to answer.

We can't know, of course, how best to respond. The way I envision it is that a million different stories play out in a million locations, each buffeted by their own quirks of locality, personality, history, random luck, etc. To me, it seems fruitful to seed the idea that recapturing modernity's glories might not be the best move. The more willing people are to give up on modernity, the better our chances of some of those million stories succeeding. As long as it will take, we're not personally likely to experience a full transition. So for now, openness to other ways of living seems like a good first step.

Yes, great article, thanks.

There was also a good essay on this topic linked by Tom W in the comments under Spare Capacity.

I second this!

The piece that Tom W pointed out is a gem. Many, many thanks!

But we could use language to create an egalitarian society that lives in harmony with nature rather than attempting to dominate and exploit it.

Language is neutral, just like technology, but the ruling classes have subverted it to their ends of exploitation, surplus accumulation, and domination.

Direct democracy will give us the power to take back control and steer our species back in the correct direction.

Such "neutral" statements are, to me, just words. Notions. Attractive ideas. Theory. Perhaps written language and technology are expressions of intent: only arise from non-neutral motivation. In any case, while it is easy to identify both positive and negative uses of both writing and technology (just as it is easy to identify Likes and Dislikes—as in Metastatic Modernity #10), one cannot in practice separate them so that the net effect is what's relevant. In these cases, I would say that the net effect is so overwhelmingly negative that talk of neutrality is a useless mental exercise divorced from reality.

While I agree that the net effect of capitalist modernity is overwhelmingly negative, there are many examples of human intelligence being used to "fix" nature rather than break it. Rewilding will be a major part of any rational response to the current ecocide, and the ecological sciences will help us do that effectively.

In respect of language specifically, I can recommend Elinor Ostrom's groundbreaking "Governing the Commons: the evolution of institutions

for collective action" for an overview of best practice in respect of autonomously managed (ie, non-firm, non-state) Common Resource Pools. The language in that book seems to have been used in an overwhelmingly positive way 🙂

I go along with Tom's reply here.

I wonder, though, what is "the correct direction?" What does "harmony with nature" mean? All species (indeed all organisms) are in it for themselves. This is what evolution works on, mutations to individuals that may or may not give them a better chance at survival and reproduction. What may be thought of as harmony is simply a fairly stable relationship between prey and predator, until something perturbs that state.

It is literally impossible for any species to be "in it for themselves" because every species relies of the ecosystem for survival.

Hobbes may have popularised the view of evolution as competition but I think Peter Kropotkin's "Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution" was closer to the truth, and most modern evolutionary biologists agree.

I agree that the competition/individual angle is overblown—perhaps because it lends credence to our capitalistic cultural mythology. It's survival of the best-fitting (in relation to the rest), not the fittest. Biodiversity tends to *expand* over time, not whittle down in single-elimination competition (until our "winner-take-all" culture came along).

No individual organism understands that they need the rest of the ecosystem. That ecosystems reach an equilibrium state until perturbed is not through conscious actions. Evolution isn't a competition, it's just evolution. Traits that increase survival and reproduction get propagated. Organisms don't think about the future. We can see that clearly with humans.

I also agree with tmurphy. Humans are not going to create an egalitarian society that lives in harmony with nature. The best chance of that happening is by people living in groups no larger than the Dunbar number (~150), within a greatly reduced overall population.

The 'authorities' are always doing their best – the road to modernity was paved with good intentions. All attempts at 'solutions' only dig the hole deeper. 'Rewilding' is a drop in the massively overfished ocean compared to the damage that has been (and is being) wrought.

Does anyone still buy the story of human 'progess'? Perhaps Nature progresses – it produces ever more complexity yet, due to the timescales, organisms fit into that complex ecosystem. But man's attempts at 'progress' have produced a too-complicated, machine-riddled hell, and have been an unmitigated disaster for the non-human world (and for many humans as well).

(On all species being 'in it for themselves' – not necessarily. Examples of symbiosis abound. Nature does whatever works, whether that be competition or co-operation. Like the 'red in tooth and claw' trope, 'survival of the fittest' is often used in modernity to justify its destruction of the environment and its cruelty to animals.)

Matthew, you make assumptions about human behavior that won't necessarily result in a non- or less resource usage-intensive world.

* Direct democracy doesn't ensure an egalitarian society.

* An egalitarian society is no less likely to pursue surplus accumulation, e.g. to sustain the community through lean times.

* Subversion and exploitation are not unique to high level ruling classes.

* Domination, i.e. leadership, can be positive or negative depending on the leader.

I don't like Tom's conclusions but it is difficult to refute them. Elinor Ostrom won a Nobel Prize for "Governing the Commons" but…I doubt that would be more tractable than similar ideas that flourished in the 1800s, e.g. Thoreau's Walden Pond, Edward Bellamy ("Looking Backward: 2000-1887"). Amish communities as they are today maybe? Not what you had in mind though.

If you have not yet read this, please do (http://www.bruno-latour.fr/sites/default/files/21-DRAWING-THINGS-TOGETHER-GB.pdf) and let us know what you think of it. Thanks.

I was reflecting on this post yesterday at lunch, and I thought back to the novel (to me) insight in Ishmael that the story of The Fall of Man is actually in reference to the beginning of totalitarian agriculture.

I wondered if perhaps there was an even earlier version of this story, which would have naturally be unwritten, in which written language was the Forbidden Fruit.

Just some food for thought: Comparing all of written history to the history of the Earth is like comparing the last hour of Dec 31, 1999 to the entirety of the 20th century.

For a brilliant analysis of how language originated and separated us from the wondrous immediate experience of the natural world, I'd recommend David Abram's book The Spell of the Sensuous. It's available free online.

The book tells the same story you're telling, Tom, but in a completely different way. I won't try to summarize because anything I say will fail to do justice to the original. Like your work, it looks at the relationship between the human and more-than-human world and offers the hope that we can find (or recover) a way that is not destructively "modern".

Another good one is Walter Ong’s “Orality and Literacy”, which examines how writing has shaped how we modern humans generally tend to think and perceive the world. He contrasts so-called literate cultures with oral cultures, highlighting how language is far more embedded in holistic modes of experience in the former, whilst the latter is pre-occupied with abstract, analytical thinking.

A bit of a taste of his ideas can be found here: https://newlearningonline.com/literacies/chapter-1/ong-on-the-differences-between-orality-and-literacy

I wonder if the development of writing creates a positive feedback loop with narcissism/a narcissistic style of communication, also much favored and encouraged by modernity. Not to mention, history is written by the 'winners'. It's fundamentally one-sided, better suited to announcements, declarations and attention-seeking performance than an oral conversation, which would ideally involve some back-and-forth. Do the skills of responsive storytelling and active listening then atrophy, leading to more writing, or potentially more self-centered oral communication? Even in my lifetime, I've noticed shifts toward more 'talking at' others – like over a period of a few years everyone I knew stopped talking on the phone and started texting, sometimes time-consuming lengthy screeds, that reflected this change, and to me made catching up with a friend feel less engaging and more chorelike – though that was minor compared to the negative impact social media has had on every kind of communication.

Fun random aside: after reading this, I was curious about what the world's best-selling books are, and what that might say about our culture and the impact of the development of writing, and then printing, then all the rest. The all-time winner seems indisputably the Bible, followed by several other salvationist religious texts, followed by… good old Harry Potter! Score one (hundred million) for the heathens, though the Hogwarts tomes are still are minor players compared to those billions of Bibles. The rest of the list is pretty entertaining. It won't be a huge tragedy if some of the 'suitcases' get lost at the airport, though seeing that The Secret was one of the only contributors from this century, along with Hunger Games and Fifty Shades, confirmed for me that civilization is most definitely doomed 🙂

Interesante artículo Tom, conociéndote me esperaba algo más largo y concienzudo, me has puesto la miel en los labios nombrando el dinero como otra herramienta de destrucción ecológica, pero te has quedado solo en el apunte. Imagino que nos contarás algo en futuros artículos, pues ya has caído en la cuenta. Mi admirado David Graeber decía que el dinero fue el invento que permitió financiar las guerras. Leí tu artículo del río en el que criticabas su último libro y aunque al principio me costó, estoy de acuerdo contigo, una lástima que se fuera tan pronto, estoy seguro que os habrías caído bien. Un abrazo Tom

Google Translate: Interesting article, Tom. Knowing you, I was expecting something longer and more thorough. You've smacked my lips by naming money as another tool of ecological destruction, but you've only left it at a note. I imagine you'll tell us something in future articles, since you've already realized it. My admired David Graeber said that money was the invention that made it possible to finance wars. I read your article about the river in which you criticized his latest book, and although it was difficult for me at first, I agree with you. It's a shame he left so soon; I'm sure you would have liked him. Hugs, Tom.

While writing may have partly enabled the current 6th mass extinction, it is the context in which writing has been used that is the cause: all that Domination Culture ideology outlined so well by Daniel Quinn and others.

Tips for Tom Murphy to study is Penti Linkola, one of the people who saw this for a long time ago: :https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OkmeYe3Uh5s&t=173s

I think any writing that involves the left brain trying to convince itself that it is not the master – especially that which seeks to snooker/skewer the left brain with its own linguistic logic – is most probably a very good thing for us modern day humans to read!

How much of writing developed to account and track debt? Also to set the rules around debt. Likely debt enabled agriculture societies to function more efficiently and damage the environment faster. What’s you opinion on Debt: The First 5000 Years, by David Graeber

A quick congrats to tmurphy. I find your posts extraordinarily insightful. This morning it occurred to me that language, verbal and then doctrine, is the ultimate prosthetic device. The airplane that we strap to our butts is, in a real sense, just an extension of the proposition, "we can fly." The "stone ax" that we use to kill a lizard to eat or defend ourselves from a tiger that wants to eat us was just a rock until we gave it that name, and told somebody. Then it was 'magically' transformed and eventually acquired a "handle" and was, 1400 iterations later, developed into an "AK-47," an awkward device for acquiring lunch but better than the rock if the tiger is the issue. Without modern language, none of this, axes, airplanes, AK-47s, and civilizations, would have existed. So language is the first and ultimate prosthetic device. When that evolved as an attribute of the brain all the rest was fait accompli, and the 6th extinction some hundreds of thousands of years later was guaranteed. Yay us.

NB. SnakeTongue, in Hebrew, was my nickname when I lived on the kibbutz, it is not a compliment, but that's what they called me.

Yes the sixth mass extinction would still be occurring, plus or minus a million years or so. As surely as tall mountain crumble, elevated chemical potentials must be eventually be expended. The Earth has trickle charged an enormous chemical potential in the form of sedimentary fossil fuels. That store is only metastable, and one way or another it would be oxidized. Humans, so to speak, are nothing more than complex enzymatic "useful idiots" whose one role is to dissipate that metastable equilibrium.

The best way to view this is as a global thermodynamic system. Imagine yourself as on an alien planet watching the spectrograph of Earth through a telescope for millions of years. With carefully observation you would be able to detect the slow storage and sudden release of energy. And that would be all you would need to know.