If you are on-board with the sentiment that we should strive to reduce the amount of energy we consume as a means to relieve pressure on a world suffering impending energy scarcity, then you probably want to know how one might proceed. In this post, I will describe the single-biggest energy-saving strategy I have employed in my home in the past five years, which slashed my natural gas consumption by almost a factor of five.

Last week, I described how to read gas meters, in the process discovering how onerous pilots lights can be. As a result of initial exploration of my energy footprint in the spring of 2007, I shut off the furnace pilot light for the summer, which I figured accounted for two-thirds of my warm-season natural gas use. When winter came, my wife and I challenged ourselves to hold off on re-igniting the pilot light until it got too cold for us to bear. That day never came. The result was a dramatic reduction in natural gas use.

In this post, I will talk about some of the ups and downs of adjusting to a colder house in the winter. Granted, we live in moderate San Diego, and could not get away with the same tactic in many locales. Even so, I will quantify the gains one might expect elsewhere for similar living conditions.

My Natural Gas History

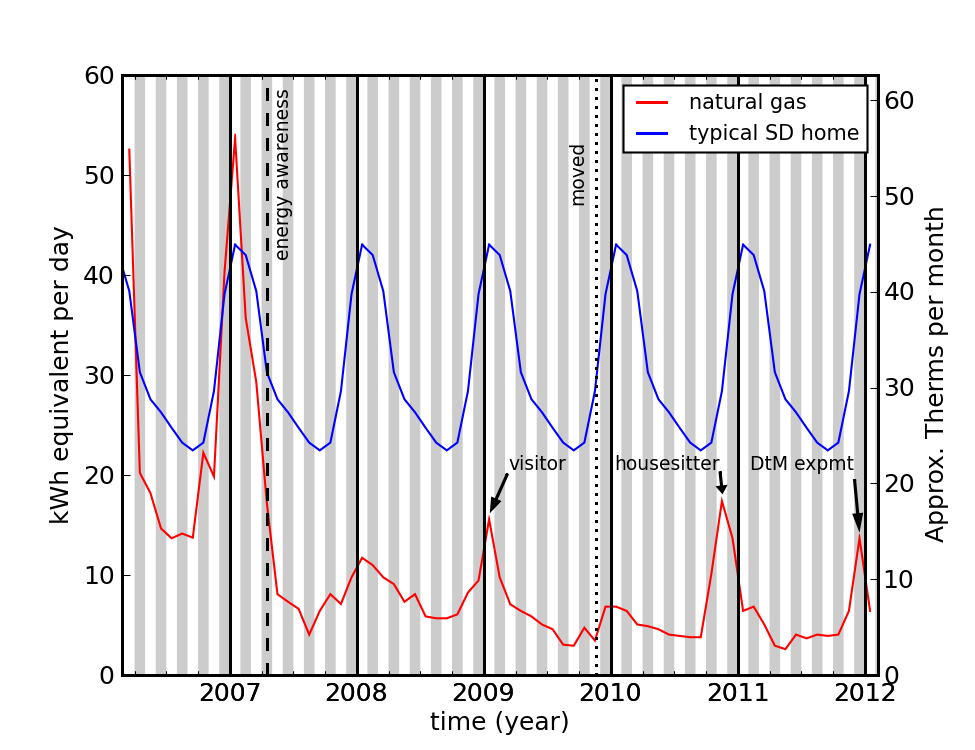

Below is a plot of natural gas usage for me and my wife since early 2006. It was at this time that we sold our home and moved into a large, 1960’s condominium that used natural gas only for heating and hot water. The data are straight from our utility bill, with a point plotted for each month (months shown as alternating gray/white stripes).

The first month can be disregarded, since we were not occupying the space yet and have no idea why the gas use was so high in March. Also shown (in blue) is the typical San Diego gas usage for a similar vintage/size dwelling that houses one or two people—as provided in the form of an online comparison tool by my utility (SDG&E).

The first month can be disregarded, since we were not occupying the space yet and have no idea why the gas use was so high in March. Also shown (in blue) is the typical San Diego gas usage for a similar vintage/size dwelling that houses one or two people—as provided in the form of an online comparison tool by my utility (SDG&E).

In the year spanning April 2006 through March 2007, we used 307 Therms of gas. To put this into familiar metric units for the plot, I have multiplied by 29.3 kWh/Therm and presented the result as daily energy use—taking into account the variable number of days in each billing cycle’s “month.” In total, we used about 9000 kWh of thermal energy from natural gas over the course of the year. If comparing this to electricity usage, keep in mind that most electricity is generated from a heat engine getting approximately 33% efficiency at converting thermal energy into electricity. So the equivalent amount of delivered electricity requiring a comparable fossil fuel outlay at the power plant is about 3000 kWh. But if this electricity is used for actual heat, we would still require 9000 kWh consumption in the house no matter what the form.

What we see from the plot is that our annual usage was pretty consistent with that of the typical San Diegan in the first year: SDG&E claims 300 Therms is typical for condos and 383 Therms is typical of detached houses of comparable vintage/size/occupancy.

But then something dramatic happened. I looked at my gas meter, and took stock of our monthly history. At first, I tried to reconcile the summertime use of 15 Therms each month, or 0.5 Therms/day—equating to about 15 kWh/day. As explained in the pilot light post, an average of one shower a day plus other uses led to an estimated 60 ℓ of hot water use per day, heated 20°C over (summer) ambient temperature, requiring only 1.4 kWh of thermal energy. How can I be a factor of ten off? So looking at utility bills with just a bit of physics is enough to expose problems—in this case the pilot lights.

Notice what happened after the dawning of my energy awareness. In the last twelve months, we used 66 Therms, compared to over 300 in the year before becoming energy-aware. Admittedly, April and May of 2011 were lower than normal because of a sabbatical quarter spent in Seattle, leaving the house unoccupied (but the hot water pilot left on). We more than made up for this anomaly, however, by an experiment I ran in December with an eye toward this post. More on that later.

Also worth noting is that we moved from the condo to a detached house in late 2009, but the gas use stayed low. Moreover, we see a dramatic change when a house-sitter stayed in our place in the fall of 2010. I don’t think the house-sitter used gas heat, but in any case used far more gas than we normally would in the house (hot water, presumably). We also turned up the thermostat for a visitor who stayed with us for a week in the condo in early 2009.

The lessons we derive from this are that:

- Gas consumption changed dramatically following paying attention to how much we were using and where/how.

- Gas use follows people, not houses. We moved: no big change. Different people in the same place: significant change.

How Cold are We Talking?

Okay, clever trick. Turn off the heat. Brilliant. But then it gets cold, genius.

I won’t deny that an unheated house is colder than a heated house. But before I get into specifics, let me remind everyone that humans are evolved animals who coped with seasons long before HVAC (heating, ventilation, air conditioning) came along. Are we really such colossal wimps now that we can’t tolerate living very far away from “room temperature?” We actually have ways to adapt to cold and heat—within limits.

We found that our house (and condo) tended to get down to about 12°C (54°F) on the coldest nights with no heat. Neither place is super-well insulated, but I would not call them dreadfully drafty either.

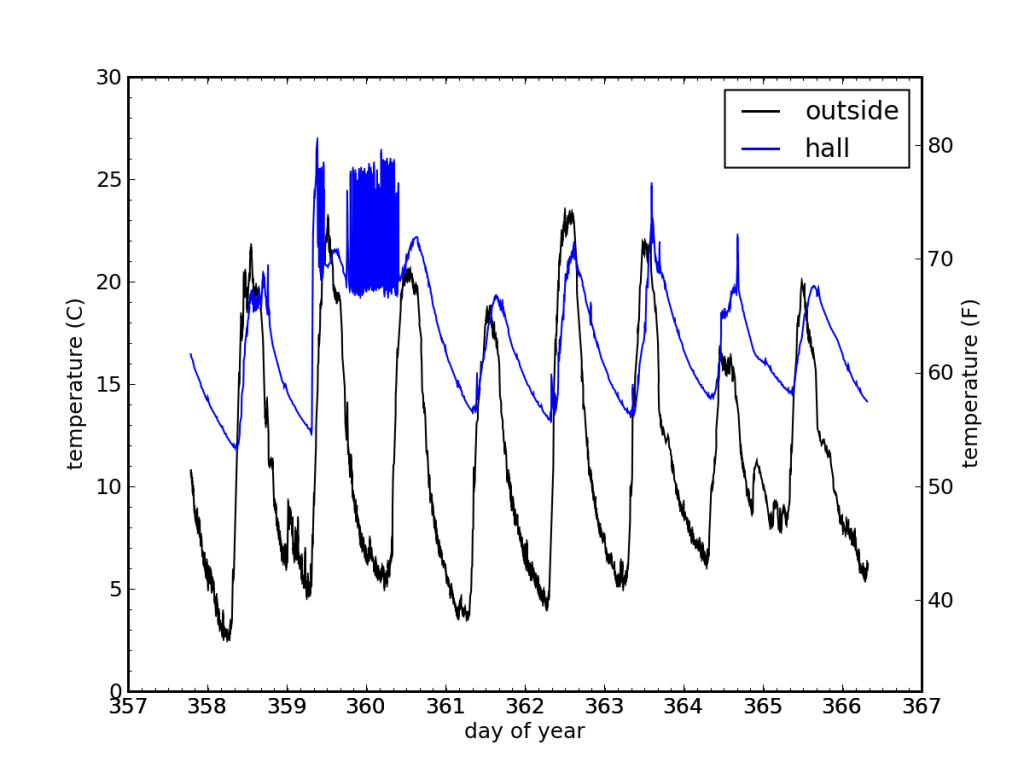

Below is a plot of temperature within our house over the course of 8 days in late December, 2011. Except for the “experiment” on Christmas (day 359–360), the house went along its usual, passive undulation. The average inside (blue) temperature—ignoring the heating period—was 16°C (61°F), reaching a low of 12°C (54°F).

Meanwhile, the outside temperature averaged about 11°C, making for a 5°C (9°F) average difference. Why would the average internal temperature of the house be warmer than the average outdoor temperature? It’s not because of the appliances within, although this contributes some small amount. Mainly, it’s solar heating through windows and rooftop. Our house is not designed to be a passive solar collector, but stick a house in the sun and some of that heat is bound to end up inside.

Meanwhile, the outside temperature averaged about 11°C, making for a 5°C (9°F) average difference. Why would the average internal temperature of the house be warmer than the average outdoor temperature? It’s not because of the appliances within, although this contributes some small amount. Mainly, it’s solar heating through windows and rooftop. Our house is not designed to be a passive solar collector, but stick a house in the sun and some of that heat is bound to end up inside.

The Christmas Heating Experiment

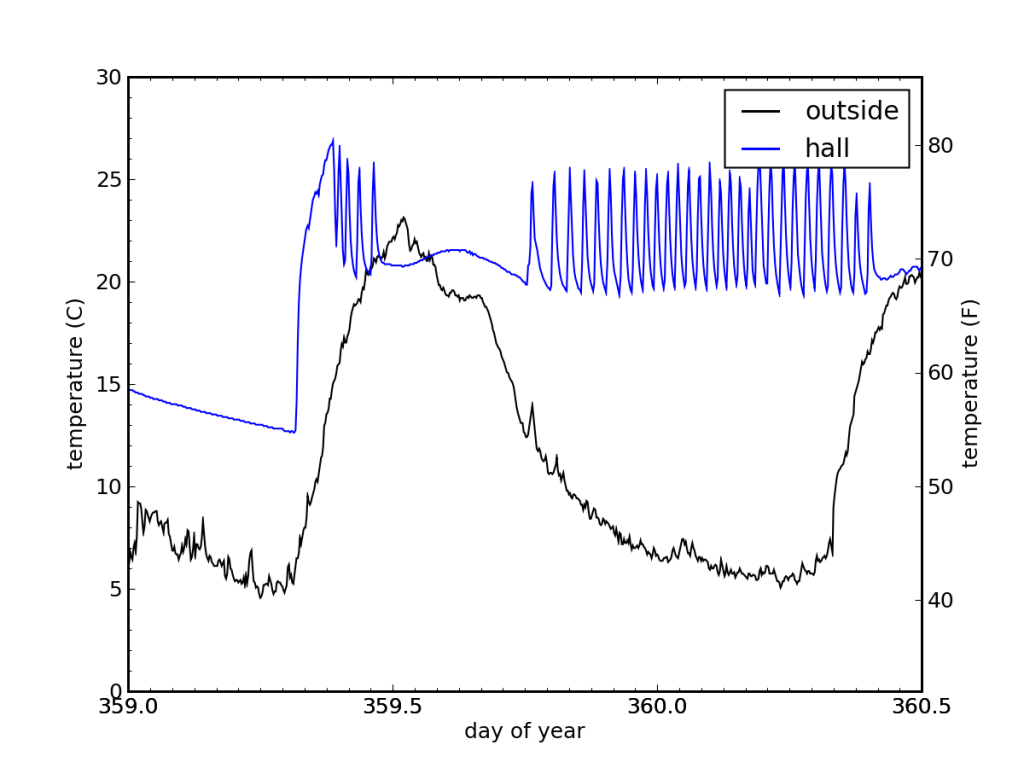

On the morning of December 25, I turned the thermostat in our house up to a toasty 20°C (68°F). Room temperature! I monitored gas consumption needed both to charge up the house to this temperature, as well as to maintain it for the next 24 hours. The indoor temperature sensor, near the ceiling in the hall, displays spikes when the heat is on and blowing hot air into the house. This appears as “hair” on the blue curve in the plot above. Below is a close-up.

Tracking the gas expenditure, it took 1.3 hcf (hundred cubic feet; 1.33 Therms; 38.9 kWh) over the course of two hours to get the house up to the set-point. Most informative is the following overnight period, when the house was fully stabilized at the set-point. The overnight period required an additional 3.4 hcf (3.5 Therm; 102 kWh). If we kept this up for a month of similar weather, we should expect to expend something like 100 Therms of gas energy in a month, compared to our average of 5. Thus our winter-month gas expenditure would be 20 times larger than our realized average rate! Instead of paying $7 per month for gas, we would get hit with $120 charges!

Tracking the gas expenditure, it took 1.3 hcf (hundred cubic feet; 1.33 Therms; 38.9 kWh) over the course of two hours to get the house up to the set-point. Most informative is the following overnight period, when the house was fully stabilized at the set-point. The overnight period required an additional 3.4 hcf (3.5 Therm; 102 kWh). If we kept this up for a month of similar weather, we should expect to expend something like 100 Therms of gas energy in a month, compared to our average of 5. Thus our winter-month gas expenditure would be 20 times larger than our realized average rate! Instead of paying $7 per month for gas, we would get hit with $120 charges!

Overall, the one-day experiment used about 5 Therms of energy, commensurate with our usual monthly expenditure: thus the extra spike on the natural gas history plot at the end of 2011. The daily expenditure of 102 kWh to heat our home translates to an average power of 4,250 W. I react with horror. We try to keep our electricity average power below 200 W, for instance.

Coping Mechanisms

First of all, I should express my gratitude that my wife is on board with living a cooler winter existence. It takes two to make such cuts a reality. Living in an unheated house was a bit of a difficult adjustment the first year, but now we hardly notice. It’s supposed to be a bit cold in winter. We wear appropriate layers, have down-boot slippers, and have an electric mattress pad on the bed.

Let me point out that when it comes to staying warm in a house, I really could care less how warm the pictures on the wall are, or the kitchen knives, or the books in the bookshelf, etc. I care how warm I am. And that’s a much easier task. So concentrate on warming the person, not the house, and suddenly you’ll find that not much energy is needed to stay warm.

The mattress pad on the bed is a key feature. It has dual controls, five steps each, amounting to about 6 W of additional power per click. Full-blast, it’s only about 60 W. Compared to a 1500 W space heater, this is impressively small, and more power than is needed to stay comfortable all night. We turn it on a half-hour before we get in bed. It knocks off the chill, eliminating the unpleasantness of crawling between cold sheets. I usually cut mine completely off at this point, relying on the down comforter plus my 100 W metabolism to do the rest of the work. Another key feature is a higher concentration of coils at the feet, where more warmth is appreciated.

Blankets on the couch make curling up for a movie or chatting with friends perfectly comfortable. My wife often sets a 40 W heating pad on her lap or under her feet when extra warmth is needed. On occasion, there might be a little space-heater action in the closet while getting dressed, or around the dining table when friends visit. For short times in small spaces, this can be reasonably effective without being too energy-egregious.

And in the end, the motivation as to why we go without heat is itself sustaining: we simultaneously have a smaller impact on the world—living more within our collective means, and we are conditioning ourselves to be tougher so that we will more easily adapt to potentially harsher situations in the future. We also remind ourselves that humans have not always been pampered with luxuriant heat during the winter, and we got by as a species just fine. Less princess; more villager.

Expectations in Other Climates

Despite the accomplishment of trimming our gas usage by a factor of five, I’m sure many readers are wholly unimpressed. “Any fool can turn off the heat in a San Diego winter—if you can even call it winter. Where I live, oh-ho! This hair-brained strategy has no chance.”

Several quick points, then some details.

- Most San Diegans do resort to heating in the winter. It’s not considered to be a local luxury. Many locals are stunned to learn that I forgo heating, and indeed SDG&E puts the typical gas usage for a home like mine at almost six times our realized usage.

- I’ll bet my house is colder than the houses of most of the people who brush aside the San Diego aspect. Those with colder houses are free to snort.

- Adopting a much cooler set-point can still have a factor-of-two impact in much colder climates.

Let’s spend some time on this last claim. Roughly speaking, the energy expended to heat a house is directly proportional to the temperature difference between inside and outside. More accurately, it is proportional to the difference between the set-point temperature and the temperature that would be achieved passively in the house. Windows admitting sunlight (plus roof absorption) generally mean the average passive temperature inside is higher than the average outside temperature, as is seen in my home.

So in a colder climate, let’s say it’s cold enough that the heat might come on at any time of day (e.g., it does not warm up enough outside to obviate the need). Let’s say the average daily temperature is freezing: 0°C (32°F). Let’s further assume that the passive temperature in the house would average about 3°C (5°F) above the ambient outside temperature. Then to keep the temperature set-point at 12°C (54°F) requires an average offset of 9°C, whereas maintaining the standard room temperature of 21°C (70°F) requires twice the offset: 18°C. This is the basis for my statement that a factor of two savings may be gained even in colder environments if you’re willing to have your house as cold as we let ours get in San Diego. Granted, it would stay this temperature all the time during cold periods. But I’ll wager it can seem normal, and will still be a comfort compared to the frigid world outside.

To get more specific, the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) keeps data on the amount of cooling and heating required based on the weather at a given location. The metric is called heating degree-days, and is effectively a sum of average departures from 65°F (18°C). A temperature slightly cooler than normal “room temperature” is picked to allow for the passive offset of a normal home. Normal values for cities throughout the U.S. on a monthly basis can be found here.

As an example, heating degree-day values for select cities are shown below, in both °C (°F) formats. Both the annual sum and the value for January—typically the coldest month—are shown.

| City, State | January | Annual | Jan. at 12°C |

| Miami, FL | 32 (58) | 86 (155) | 0 |

| San Diego, CA | 126 (227) | 591 (1063) | 0 |

| Atlanta, GA | 384 (692) | 1571 (2827) | 0.27 |

| Washington, D.C. | 503 (903) | 2222 (3999) | 0.45 |

| St. Louis, MO | 609 (1097) | 2643 (4757) | 0.54 |

| Seattle, WA | 415 (747) | 2665 (4797) | 0.33 |

| Boston, MA | 613 (1104) | 3128 (5630) | 0.54 |

| Minneapolis, MN | 898 (1616) | 4379 (7882) | 0.69 |

| Anchorage, AK | 848 (1526) | 5817 (10470) | 0.67 |

Since January has 31 days, we can divide each of the January numbers by 31 to get the average offset from 18°C (65°F). For instance, San Diego’s average January temperature computes to 14°C (58°F)—a bit warmer than the period displayed on the 8-day temperature record above.

In Atlanta, the average January temperature lands at 12°C cooler than the 18°C reference point, putting it at about 6°C (42°F). Maintaining an indoor temperature of 12°C therefore costs one quarter of the energy as maintaining it at 21°C—again relying on the standard 3°C bonus from passive solar heating. To see this more clearly, the passive house would average 9°C when it’s 6°C on average outside. To bring the average to 12°C requires a ΔT of only 3°C compared to a ΔT of 12°C needed to achieve 21°C inside. Thus the one-quarter expenditure.

Before objecting that clouds nullify any passive gain: not true. Diminished, yes—but not gone, actually. Moreover, clouds keep your house from losing as much heat—especially overnight—by blocking radiation to space. In any case, the 3°C offset implicit in the NOAA data is there for a reason.

In the table, I have also included the fraction of heating energy that would be needed in January if thermostats are pulled down from 21°C (70°F) to 12°C (54°F). In essence, this reduction frees up 279 degree days (31 days times 9°C) for anyone who still needs to run heat to maintain a 12°C house in winter. Even in wickedly cold locations, a substantial savings may be affected. And this is in the worst month. If I do a similar calculation for Minneapolis across its coldest 7 months, I find a 50% reduction in total number of degree-days to maintain 12°C instead of 21°C.

How much heating energy does a monthly 279 degree-day savings translate into? One handle I have is that my house used 3.5 Therms to stay toasty on a night that totaled 6.9 degree-days below the 18°C reference point (possible to assess from overnight dip in close-up plot of day 360 above). So my house uses about 0.5 Therms per (Celsius) degree-day offset. Applying this scaling to 280 degree-days means a potential savings of 140 Therms, or about $170 at the rate I pay for gas service. A smaller, better-insulated house will require less thermal energy per degree-day. Scouting a bit online, I find that my house is not great (no surprise that a San Diego house would not be built to good thermal standards). In colder climates, houses tend to be built with heating efficiencies around 0.2–0.4 Therms per (Celsius) degree day. Divide by 1.8 to get the equivalent Fahrenheit measure. So for a more reasonably insulated house, shaving 280 degree-days by adjusting to 12°C instead of 21°C should save about 70 Therms, or close to $100 each month. A bit of that might get eaten up in blankets, down slippers, and mattress pads. But these things will last years.

For assessing the heat-tightness of a house, we have several units from which to choose. The Therms per degree day measure may be somewhat convenient in the U.S., but a more natural unit is W/°C. One Therm per day equates to a power of 1.22 kW. Here is a useful table for comparison for U.S. houses in the northeast, midwest, and west with a square-footage of 2000 ft² (186 m²). Data are from this useful website.

| Characteristic | Therms/deg-day (°F) | Therms/deg-day (°C) | W/°C |

| Best 10% | <0.1 | <0.18 | <220 |

| Typical | 0.2 | 0.36 | 440 |

| My House | 0.28 | 0.5 | 610 |

| Worst 10% | >0.5 | >0.9 | >1100 |

One caveat worth pointing out: the amount of savings calculated in the foregoing paragraphs is based only on average temperatures. This will work perfectly well for the months when the outdoor temperature stays well below the set-point (by at least 3°C) all day. In milder weather the daily swings may still force the heat to come on in the wee hours, even if the calculation based on averages suggests that heat will not be needed. A well-insulated house will suffer smaller swings and may be able to resist kicking the heat on during the nightly cycle.

Implications

We are not utterly victim to our energy demands: we create those demands. Adopting an attitude that houses do not need to be warm as long as the person can remain warm means that we can have a substantial impact on our energy use. By adopting a winter-time set-point temperature that would be thought of as a mild spring day outside, we could slash our national heating demand by a factor of two at least! Further reductions could come in the form of smaller houses (or heated areas within houses), better insulation, and deliberate enhancement of passive solar heat inputs.

So. Are you ready to be a low-heat trooper, donning layers and blankets, or do you insist on shorts and tee-shirts inside in the winter? Perhaps our ancient ancestors would have opted for the same, given a choice. But they survived their winters, and we’re made of the same stern stuff.

Addendum: Position Statement

In this and other posts that I write about energy reduction schemes, please note that I am not trying to establish my own efforts as superior (my location plays a big role in my success). Lots of folks have been far more effective than I have been in reducing energy usage—and they have my admiration. For me, reduction by factors of 2, 3, 4, etc. are satisfying enough to give me a sense of what can be done. I am now more interested in getting more people to catch up with me than I am in pushing to further extremes. Also, Do the Math readers may wonder why I fuss over home efforts, when many of these tactics do not directly address the impending liquid fuels shortage—identified as our biggest near-term hardship. My answer is that I have adopted a philosophy that all energy is precious and that its consumption (together with consumerism) should be reduced as substantially as we can tolerate. At scale, such an approach relieves pressures on many fronts: environmental; transport; agricultural; resource depletion; etc. Let’s not dink around, and instead change the game across the board. We have the power!

Views: 19151

Speaking of keeping the person warm, not the house – I’m surprised you did not mention drinking warm water (/ coffee / whatever). I live in South Texas and have the opposite temperature problem; but have reduced energy use by raising the A/C temperature. To compensate, I load up on ice water and found that its fairly effective at keeping me cool. I imagine the energy needed to make ice-cubes (or hot water) is less than that needed to heat / cool the entire house. Thoughts?

A/C is the same concept though for some reason i feel like the math plays out differently due to the efficiency of the A/C unit, appliances, cooking, and the fact that passive heating is working against you.

For me i run the crap out of my A/C during the summer because i would RATHER pay to have it cold than be hot (most peoples mentality for the winter). My thought though is you can only take off so much clothing in the summer. However, in contrast to that concept I dont turn on my heat in the winter (near DC) because i like it around 50 or so and dont mind wearing a shirt and sweater and then being under a blanket. Being in a studio and all electric i end up with $40 winter bills (no heater just an always running pc server) and $150 summer bills (AC set at 73 from 80-90) and find the money well spent. I know that thinking is against the spirit of this blog but 99% of people arent going to change wihtout major motivation.

Cooling requires the magic of heat pumps, which can move X amount of thermal energy for an energy input of X/N, where N is typically around 3. So it can actually be more efficient to cool by a certain ΔT than to use direct heat for a similar ΔT. But then power plant loss makes it a wash again when comparing electric A/C to direct gas heat. Then we have the fact that most place require more heating than cooling. Heating degree days becomes equal to cooling degree days in places like Macon GA or San Angelo TX.

I’ll eventually do a post on heat pumps, and perhaps also a romp through HDD, CDD data.

In my contry (Spain), the electrical energy production mix is as follows (2010 data):

·CCGT plants: 26%

·Fuel/Gas: 3%

·Coal: 11%

·Nuclear: 8%

·Hydropower: 20%

·Wind power: 20%

·Solar: 4%

·Other renewable: 1%

·Other non-renewable (suchs as cogeneration): 11%

Then, assuming that only 40% of the energy comes directly from fuel thermal conversion into electricity, heating pumps are a quite interesting choice, specially in the south, where temperature seldom goes less than -5ºC/23ºF.

Otherwise, interesting article. We shouldn’t forget the key idea: we must keep ourselves warm, not our entire house.

Carlos: I love Abengoa. To view the plant and its glow in the atmosphere as one approaches from the highway is truly inspirational. Don

Also about keeping the person warm (and at the risk of spiraling off topic): A similar problem is faced by the makers of EVs. Previously heating was free, but in an EV heating the inside space of the car can easily cost half your range in a cold winter! So car makers are looking into what actually makes a person _feel_ warm: We can expect more heated seats, heated steering wheels, and warm air blown only at the few leftover exposed places like neck and ankles.

That’s my big complaint with my Leaf — the heating system. The other day I barely made it home from my mom’s house with only 9 km left because I didn’t feel like freezing and had the heater on (actually, I was very carefully monitoring my remaining range and would have turned it off if it was going to be a problem).

My suggested solution is to have a little propane heater under the hood that you can hook up those little camping canisters to. Sure, it comes from FF’s, but then where does the electricity come from to power the EV, and how was it manufactured? Until the supporting infrastructure is developed for EV’s I think they need to bend the rules a bit.

Nissan says they are working on a more efficient heat pump system for newer models, but below freezing this won’t be any more efficient than direct electric resistance heating. Unfortunately, you want your heating the most when it is below freezing…

Actually I just checked heat pumps on Wikipedia and even below freezing the air source ones have a Coefficient of Performance of 2 or 3 so that’s still better than resistance heating. But still, the colder it gets outside, the more heating you want, but the more inefficient the heat pump becomes.

I hear some manufacturers want to put in bioethanol auxilary heaters. I guess it sounds better when the fuel contains some bio…

Anyway, get a heating blanket! Seriously, you can get aftermarket heated seat covers that run from your 12V cigarette lighter plug (I assume the leaf has one?). kW for heating the air in the car. And it’s on faster, too.

Not sure about heated steering wheel covers, the wiring might be tricky if you still want to go around tight corners… 🙂

Actually, the Leaf does have a heated steering wheel and seats but I’ve never been fond of warm seats.

Bikers and snow machine users in cold climates use heated suits, gloves, etc already. But for EV, you wouldn’t need the road rash protection, so a warm suit for EV could be much lighter and cheaper. I have personally found that if the torso, butt and fingers are good, the rest can get by just by being well insulated. They necessity is defrosting the windshield from your breath…

Most heated gear doesn’t have the protection built in these days, it just consists of liners. This would be doable, but cars have that annoying glass that tends to fog up in cold weather and would probably quickly derail any attempts at energy savings on anything but the shortest of trips. Singing along with the music tends to make this rear its head quite quickly, in my experience.

There’s an old saying: if you want to keep your feet warm, put on a hat. Clothing and the simple expedient of drinking hot liquids will keep a body comfy down to about 50F (10C). And get up and move around, for heaven’s sake. You put $$$ in your pie-hole — Calories are extremely costly fuel — so use that stuff up.

I admit I was skeptical when the topic switched to personal conservation, but I’m hooked. One question, though, for Tom or anyone else who may know:

Implicit in the notion of making sacrifices in the name of personal conservation is the idea that the market pricing mechanism is broken and that retail energy prices are too low. For example, I can afford an extra $100 per month to stay warm in winter, and in terms of personal comfort, I’d consider that money well spent. And yet, the thrust of your posts (and I don’t necessarily disagree) is that I shouldn’t spend that money but instead should conserve scarce energy resources. But conserving scarce resources is the whole point of market prices, so why aren’t market prices sending proper signals in this case?

This seems like an important question, because I suspect the best hope for convincing people to use resources wisely is to charge them the proper prices and let them make choices based on their pocketbook.

I think this is a tremendously important question. Markets claim ignorance about the future via the discount rate. It basically says: you can’t dream of what amazing things may lie around the corner, so might as well use what’s available now to the full extent possible, since tomorrow is a whole different ballgame anyway.

For me this is the EXACT reason math & science are useful to show this isn’t the case. And with that said if the market doesn’t think to address this issue at what point should government step in. Ie should we rely on individuals (doesn’t seem like that large and impact if ~1-5% of people act) or have government make us pay 2 times the current value for energy while installing the alternatives you wrote about? That would ensure that when fossil fuels are more expensive without taxes that the alternatives are already in place. In the summary of energy types “political will” was addressed as a negative aspect of that type of power, any chance that the piratical wide spread adoption of such things as home heating will be compared against anything?

Right. Math and science persuaded me that we have a problem, and that action is required. The problem is that I can’t prove that things just won’t all work out via innovation, substitution, and all the other visions of sugarplums dancing through economists’ heads. Persuasive arguments exist on either side. But it means something to me that scientists tend to land on the “worry” side.

Nonetheless, we can’t get political action (in a democracy) until the majority of people accept the arguments that we should pay more for energy—since the market is too short-term to make that happen. And standing in the way of this is the complexity of the situation: it’s hard to make an iron-clad case that we must change our ways. I’m personally convinced. Others are too. But getting more people to come to the same conclusion is a colossal challenge. It’s why I started DtM. And while I never expected over a million pageviews in the first 8 months (wait for it…), it’s still a small number of self-selected people. Hopefully those people will be persuasive with their friends and family. What other methods are available to us, save crisis?

Tom, your original comment reminded me of what Julian Simon wrote about resource conservation: “asking us to refrain from using resources so that future generations can have them is like asking the poor to make gifts to the rich.” (I suppose the same argument could be made with respect to climate change mitigation: our descendants will be wealthier, ergo let them deal with it.)

This assumes that the future will be richer and that real economic growth will continue indefinitely. Reaching such a conclusion is far easier, it seems, when one completely ignores the contribution of high-quality fossil fuels or natural resources or climate stability in economic growth models. But after reading your blog (and the works of physicists-cum-economists like Robert Ayres and Reiner Kummel, who examine energy’s role in economic growth), such assumptions seem irresponsible at best.

While markets are prone to random short term fluctuations they tend to be reasonably efficient over the long term, and the price of oil has been climbing over the past 10 years. Also it reflects political considerations. Theoretically big investors like Jeremy Grantham who believes we are near the limit would buy futures in oil and send price signals that oil is likely to be more expensive, but when politicians campaign on $2.50 gallon gasoline, such behavior is likely to be attacked as evil speculating driving up prices and attract a “windfall” profits tax if the a lot of money is made.

Just wanted to add to Tom’s reply.

The Market is a model for the physical world that is meant to allocate resources in an optimal manner. The problem is that the model is incomplete and inaccurate. There are many economic externalities (aspects of our world that are not included in the model), such as the services provided by the natural world (contributes to GDP), pollution (no cost is generally attributed to pullution), trashing the commons, etc.

Because of this, I think the market greatly undervalues certain goods and services. Energy is but one — others are fresh water, topsoil, fisheries, forests, etc.

This is obviously a very North-America-centered post again, where houses tend to have very small thermal mass even if they are reasonably well-insulated.

I live in an apartment building in Germany and I only turned on the heat for about two weeks this winter. Inside temperature never dropped below 18°C. This is of course in large part due to my neighbors still heating my walls, but those are solid concrete so they would provide a decent thermal mass even without the heating, and I’m guessing natural day/night swings would be less than 5°C. This becomes obvious in the summers, it really needs to be baking outside for several weeks before the place gets uncomfortably hot (i.e. >25°C). This doesn’t change the heating requirement for a set temperature on average, but it significantly reduces the most uncomfortably cold period at night if heating is switched off.

only semi-related: What do you use for your figures? python? gnuplot? something else? Would be great if you could post the source, so people can play with the numbers more easily!

North-American-centric, yes. But you’ll at least give me some credit for using °C as the primary measure of temperature…

As for plots, etc., I use Python and matplotlib. Good idea about posting sources. I’ll look into what it would take (time-wise) for me to do so. You may force me to comment my code!

I like what you’re saying Felix! Here in the Netherlands (that’s next to Germany if you’re wondering) I use a simple rule of thumb for quickly judging the insulation of a home:

If you turn down the thermostat in the evening before going to bed, how much is the temperature drop over night (during a normal winter night: around freezing):

4K Go insulate your home better

But this all comes down to thermal mass versus insulation.

I agree with you that it’s US-centric, but I think it’s generalisable.

I live in Brisbane, Queensland. It’s subtropical, and the houses are very simple with poor insulation and little thermal mass. We don’t use heating or cooling in our house, which is nowdays a rarity here. Our house drops to about 8 degC on the coldest winter nights, and consistently reaches 30 degC on hot summer days (about 1/4 of the year).

This is considered unbearable by most Queenslanders now, whereas 30 years ago they would have turned up their noses at A/C in summer as being for Southerners (where it’s colder).

I think this is a great post, thanks Tom, and that it bears generalising further. Eg. what’s wrong with cycling in the rain and snow? I did it in Edinburgh, Scotland and loved it. There’s no such thing as bad weather — just the wrong attitude (apologies to Billy Connelly)

Thermal mass is definately an asset within well insulated enclosures, but that mass still needs to be periodically “charged”.

Passivhaus design has achieved incredible reductions in energy requirement.

But there are many climate zones in this world in which you could still easily be frozen out of a passivhaus without some energy input beyond solar gain.

I think Tom is lucky to live in such a pleasant climate.

To deal with energy scarcity in Alsaka, one would have to live like the Inuit.

Or purchase a house something like these – PH in Alaska:

http://passivehouse.us/passiveHouse/2010_Passive_House_Conference_Presentations,_November_6_files/2010%20Conference-Passiv%20Haus%20Alaska-Thorsten%20Chlupp.pdf

They’re a bit like moonbases – forgive the space reference.

Thank you, Prof Murphy! I judge this to be your best d•t•m essay yet, after «The Energy Trap». (The rest are merely excellent.)

It is wise to preach that energy savings are gold. And Californians once knew that “Gold is where you find it.” Interesting, how you found it in your own home. (This ties in with a non-Koran parable told by the Prophet Mohammed, interesting but off-topic.)

You wrote about heating (or lack of same) in «winter». There is also cooling in summer, a major concern for Midwesterners of today. My late mother lived alone in a large house for three-plus decades after my Dad died and her kids moved away. In her 90’s, she told me she would have died already, were it not for air conditioning. But spending on it was against her frugal nature. She had a window unit in her bedroom (the smallest room in the house), which was off during the day. Next to her favorite chair in the living room was another very small unit. She experimented with screens. She did most of her cooking in the morning in hot weather. When the heat went beastly, she went into her bedroom, behind a closed door, and read.

She commented that she didn´t care if it was beastly hot for the curtains on the windows or the china in the cabinets, but she wanted to be comfortable. Along the lines of your observation.

She also commented that, what with people having to climb into a car and drive to a “health club” to get exercise, no wonder the environment, the economy, and the public health are all suffering.

I am always amazed at those that poo-poo others who try to save. Money saved is money saved. Each of us has to find the right level of efficiency. I personally like things warm so I keep my condo in Chicago warm during the winter, but hardly use AC in the summer. This is my comfort level and my bills are within reason to me. I did an exhaustive analysis on Elec bills once and I was low enough that the cost of being a customer (service plus fees and taxes) was almost 50 % of my bill. Which makes that first KWh very expensive.

Tom, or any homeowner, could see even better numbers if he insulated his house and possibly put a Solar Thermal water heater on the roof. Run a set of tubes thru the floor and divert hot water during the winter months. Seal the windows up and other simple maintenance things like this that help save money over time.

As mentioned in the Addendum, money save on the home can be used to buy more liquid fuels without affecting your overall budget. As cost of things you cannot control go up, you need to increase income or decrease usage. You can get a car with better mileage or save money somewhere else.

Those who dismiss efforts to save likely feel threatened (challenged to justify their wants and not liking the answer within), or are simply put off by a perceived righteousness on the part of the saver. No one likes to feel bad about themselves, and unfortunately pleas for reduction often trigger such reactions. Defensiveness is an expected response.

Well, it’s also invoking stereotypes of environmentalists as people who want us all to “shiver in the dark”.

I agree – I see three layers to this.

First there is the true observation that we can often have “all that matters” with much less energy expenditure.

But then there is the attempt to define for others “all that matters”, and that’s where things can get sticky. Do you really *need* a Gaming PC with a 200W graphics card?

And ultimately, there are the Kunstlers of the world, putting fences around their backyard, defining “all that matters” as “good old days, 1950’s, alternate universe”. Do you *really* need an electric blanket? More manual labor will keep you warm and exercised.

I am completely on-board with personally doing more, or the same, or less, with less, from personal initiative, and with a clear understanding that there is neither a requirement nor a commitment to revert to a “modest lifestyle” that never was.

Incidentally, there are large forces at work shifting a lot of the frivolous/harmful accomplishments of our time – such as mobile computing – towards “low(er) power”. Moore’s Law is becoming performance/Watt. I don’t know what the life cycle energy expenditure numbers are, but replacing every 40″-plus HDTV with an 10″ iPad-style slate might be a net gain – breaking the “glass teat”, or depriving the “nuclear” family of its cable channel hearth and heart?

In a way, a huge number of individual, “local” optimizations are not going to take us backward, or even frogmarched in one direction – more like side-ways in many directions. As for houses, the question might well not be how we heat them, but how we build them, and for how long. “Low thermal mass” is often just another word for throwaway cardboard boxes. But then, houses as homes – the pschological investment into them, their ownership over time – are one of the clearest expressions of equality – or lack thereof – and in a society that is content to throw away people by their unemployed millions, is it any wonder houses are often little more than packaging material and moving crates?

Tom:

Way ta go! Karin and I have also been practicing the wool sweaters and sheepskin slipper approach to winter up here in Davis, which is “Alaska” compared to San Diego. However, we get killed at Christmas when our kids with granddaughter visit; they don’t share our esthetic (lawyers and a banker—our failing!). The kids stayed for weeks this last Christmas, and they were brutal on the terms. The pilot light monster can be slayed, however, and we are on the verge of switching to on-demand electric water heating, or OD gas water heating if we can get a pilot light-free model. Note the climbing rate. Usage went up, but I believe that the rate structure also escalated.

PG&E

Therms $ $/therm

2009 272 $266.42 $0.98

2010 294 $316.22 $1.08

2011 343 $381.57 $1.11

As much as I yearn for solar panels, they are an expensive investment relative to conservation, especially for people approaching middle age, like us; we go back and forth on the wisdom v. ethics of solar panels. We will soon invest is in a much smaller, energy saving, refrigerator. And note the rate change in electricity based upon usage, below. We are going the right way on electricity and the wrong way on natural gas. Hanging clothes on the line instead of using the electrical clothes dryer gave us most the gains between 2009 and 2010; we have brought usage down a great deal in the early months of 2012. Note the escalation of rates in the last year.

Don

PG&E

kWh $ $/kWh

2009 4394.48 $508.47 $0.12

2010 4488.1 $515.48 $0.11

2011 4002.21 $467.92 $0.12

Whoa. Your furnace had … a … pilot light? Past time to upgrade.

A future post on how to compute when to upgrade may be helpful to many readers here. Folks may wish to upgrade but should “do the math” first.

We replaced laundry equipment in January because the 1995-era Maytags were at end-of-life and needed $300 worth of service to keep going. Penciling out the cost of new equipment, less rebates, discounts, and incentives, then factoring in repair cost on the old stuff and lifetime of those repairs, and lastly computing water and power costs of new equipment showed a break even in 18-22 months on new equipment that has a ten-year lifetime. Cha-CHING, buy it.

The lesson: consider the total ownership costs (capital + expense), not just energy. Remember, capital equipment costs have an energy price built into them, specifically, the energy cost of manufacture.

Anchorage, reporting in! Glad to see the town get some recognition. I moved up here just over two years ago, and as I write it is 7 degrees (F).

I noticed a curious thing this winter. The local gas company had a “heating emergency test,” basically, in case supplies of gas run low, they want to make sure they can quickly communicate that fact to residents, and tell them to set their thermostats down to conserve supplies….down to 65.

I was astounded! I thought my local Anchorites would be better acclimated than that, and _already_ have their heat set to 65 (or lower!) That’s where I set mine, and I’m a new transplant, not a “tough” Alaskan (but I do have a pretty awesome pair of slippers, and am never out of a sweater or thermal shirt.)

My wife and I just bought an older house, and again I was astounded, because it had less than a third of the (now-) required amount of attic insulation. Heat was just being thrown out the roof, for decades, for want of a couple thousand dollars of shredded fibers, which would have paid for itself in just a couple years. And we’ll shortly be adding more, along with other enhancements, as part of a government home energy efficiency program we’ve signed up for.

It really is amazing how much low-hanging fruit there is. It may not save the world (although it might help) but people really can save themselves a lot of money very easily.

Not only has Tom created an amazing blog….. his visitors are pretty mind blowing too!

I live in Australia. When I discovered all the things Tom discusses here over the period 1993 ~ 2000, there was no way I could stand still and do nothing. So we decided to totally convert our lives to sustainability, and frankly, I can’t understand why there isn’t a rush to do so everywhere, we certainly have not looked back.

I built a passive solar house that needs zero heating and cooling (http://damnthematrix.wordpress.com/mon-abri), even though over the past five or six years we have experienced anything from -6C to 43C….. because even when we hit -6C, it was still 16C inside, allowing me to stagger half asleep and fully naked to read the digital thermometer readout!

Our electricity bills, prior to our last solar splurge, were near zero with just 1.28kW of PVs to produce all the energy we consumed. Cut all your domestic overheads like this, and you no longer even need to go to work for wages….. so reducing our electricity consumption (and many other things) has also cut our driving very substantially. This domino effect of reducing consumption is really amazing…

I live in Toronto which qualifies as cold. When choosing our house I tried to be very conscious of energy use: we moved into a new Townhouse within biking distance of my wife’s job and transit access to my job. Built in 2006 it meets improved insulation and efficiency requirements, and we have a high efficiency furnace.

By definition, our house has two walls and a roof instead of four walls. So we use three-fifth the heat. I will agree that sharing a wall is not ideal and it is important to be wary of and friendly with your neighbours.

My in-law’s house, approximately 60% larger than ours, heating bill is up to four times as much.

Anyways the economy did us an energy disservice: my wife got a much better new job, and I switched offices, so now we both drive, single-occupant, a significant distance to work.

Tom,

Have you considered having an energy audit done on your home?

I’m not that familiar with your climate zone, and if you can already coast through a winter without firing the furnace, then maybe upgrading you home’s energy performance is not-so-important…

A blower door test can show you where the worst of the drafts are.

Often it doesn’t take much to seal these up with some canned foam – concentrate on sealing the lowest and highest parts of your house.

If you have a vented attic space, blowing in extra insulation is an easy and affordable way to upgrade you house’s insulation.

Again, I’m not sure if this would be a priority for you, but it might help make things more comfortable for you “villagers” 😉

It’s true that improving our house would not save us any money/energy, since we don’t really put any into heating/cooling. But it would make us more comfortable. So the question is: do we spend money/energy on something non-essential but nice? I’ll likely chase after the low hanging fruit—as much as anything out of curiosity for how much improvement is to be had (accompanied with data, of course). Just a matter of when I get time…

You know what would be interesting to see, just out of curiosity and time permitting of course…

A comparison between:

The amount of energy consumed keeping yourselves warm with active “technologies” (like heating blankets) in combination with a “normal”-calorie diet and;

the amount of energy consumed keeping yourselves warm strictly with passive “technologies” (like sweaters) in combination with a high-calorie diet.

Because your climate is not-so-extreme, it may be possible to set up an experiment along these lines – in many other climates it would be dificult to remove components of active energy input from the experiment.

Of course, it would only be an interesting comparison if the “high-calorie” diet is sourced from low “emergy” foods (ie: homegrown root vegetables). Otherwise, (ie: consuming “Big Macs” to stay warm) I could probably make a good guess at the outcome.

You didn’t say anything about improving your house’s insulation. I’m curious about why you haven’t done more, particular when it has a direct effect on your (and your guests’) comfort?

See my response to Lucas on similar topic.

In my municipality apartments are required to be heated to 68F. A building owner couldn’t say they were only going to heat to 60F and the rent will reflect lower energy costs. On the other hand they are likely to supply the cheapest appliances that use the most electricity if the tenant pays for the electricity since tenants are not likely to actually calculate monthly energy use for different apartments..

This reply touches on a more general concern of mine: Many of the energy saving tools presented in this and other DtM posts are simply not available to apartment dwellers (yes, we exist even in the U.S.).

I live in central MA, which is slightly colder than Boston in the winter, and vice versa in the Summer (no ocean to regulate temps). We never turn the thermostat above 60 (F) in Winter, and only air condition a medium sized bedroom in Summer, but the apartment is ~100 years old. While I can caulk windows and baseboards, I cannot, as a tenant, install solar/wind farms on the roof, update the water heater, grow produce in the yard, etc (despite having a VERY cooperative land lord). Any advice?

On a related note, my office mates and I need to have the AC at full tilt with the windows open to get the indoor temperature below 70 (F) on 30 (F) Winter days, with the steam radiators turned completely off. We are on the third floor of a building that is (you guessed it) over 100 years old. The only way for us to reduce our energy use would be to turn the A/C off and accept that it will get UNCOMFORTABLY HOT IN THE WINTER! (4giveLongPost)

simple: Give your rent money to a landlord who does energy-related renovations. Vote with your wallet, it’s the only vote you get.

And how does that trick with having too cool the office in winter work? Are you all running server farms under your desks? In that case get a proper server room and pipe outside air through. Or is the adjacent cubicle a steel forge? In most other cases see first answer above.

Actually my landlord has steadily added insulation/new windows (above and beyond anything I have heard of elsewhere), but for the property to not be a net financial loss, there are only so many renovations that can happen at a time.

In the office I think the majority of the heat comes from downstairs, and solar through the roof. It is really unbelievable (we have just 4 or 5 PCs in a ~30X50m space with high ceilings)

You can lobby the landlord to do such things, asking “why not?” and providing information. There’s also the comfort that you probably use less energy simply by virtue of being in an apartment: less heat loss from a big building, shorter distances to travel… this may be more convincing for me in Cambridge not far from the T. 🙂 Then again, I don’t even have a thermostat just radiator valves plus naked steam pipes, and often open the windows in winter to vent unwanted heat…

I noticed the other day that Cambridge has a co-generation plant, which means that your heat could potentially be coming to you from the waste heat generated by a power plant (or hot air from Car Talk Plaza). In that case, opening your windows is no worse than not having the co-generation! (obviously in an ideal world we would also be very frugal with the waste heat so that it would serve more customers)

Tom, once again, great post. I think at some point you should write about the issue of single family houses and their effects on energy consumption. The US (and Canada) has adopted the idea that a single family house with a front and backyard with a 2 car garage is the “American Dream.” That dream (an unsustainable living arrangement) is the primary reason why the US uses so much oil for transportation and energy for heating/cooling!

A lot of the commenters point out that they live outside the US in apartment blocks in Europe. Our living arrangement enables us to use less gas for heating and little oil for personal transportation because the vast majority of us live close to a train station. Shopping, entertaining, business, etc all revolve around train stations in the main cities in Europe.

That’s the reason why New York City is the most environmental city in the US. The per capita consumption of oil and natural gas is probably the lowest in the US.

You “could care less”?

David Mitchell points out what’s wrong with this phrase far more wittily than I ever could- see http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=om7O0MFkmpw

I try not to pick nits with other people’s grammar, especially someone whose writing I admire as much as yours, but this particular phrase riles me because it seems to belie that same kind of unexamined force of habit which you are doing your best to try to stop.

Anyway- thanks for reminding me to go home and turn my thermostat down!

Funny. Bringing logic to language is an interesting pursuit, to be sure. But a maddening one. English is especially illogical—particularly in spelling conventions, but also grammatically speaking. I can make sound arguments for why “proper” grammar is often illogical and wrong from a physicist’s perspective. But I get vociferous push-back from language aficionados because that’s not the way we do it. It’s more of a club obeying strange rules than a group seeking a logical approach to language. I often cringe at the ruefully illogical things proper grammar makes me do. So I’m all for logic in language, but I have to admit that I’m perturbed by those who attack universally-understood colloquial phrases when the bigger problems are defended. It seems a form of snobbery.

It’s especially interesting when the less-educated adopt a convention that is more logical than the “correct” way (and they choose it because it makes more intrinsic sense, while the proper way has not been stamped into them). It does not stop the language-elite from defending the strange conventions, and becomes part of the basis for ridicule and division.

Agreed. To me, the rhetorical and emotional power of “I could care less” is far greater than “I couldn’t care less”. The former implies something like “I could care less [about x], but the effort and attention it would take to care less isn’t worth [x]”, adding further insult to the merely factual way of saying it in the latter. Not seeking to start a language debate here, and of course I’m clearly suspect because my coder-mind put those periods and commas above outside the quotes…

Anyway, thanks for your outstanding posts, Tom!

Here in Santa Cruz, California, my small duplex (“semi-detached” for the UK-Euro folks reading) uses gas only for water heating and a wall-mounted heater. The water heater is new and quite efficient and well-insulated, so the main culprit here, as with your house, is the heater and its pilot light. I only heat the one main room, and extinguish the pilot April – October. Your math is convincing me to keep the heater off year-round.

I don’t heat the bedroom, and in fact most nights, even in winter, I keep the window open. I discovered years ago that I sleep better when the room is chilly rather than warm. I do have lots of covers. My addition to your suggestions for heating the person not the space is covering your head. I usually wear a knit wool cap or a cyclist’s under-helmet head-warmer. As I learned years ago backpacking, and one of your other readers mentioned, “Feet cold? Cover your head.” It’s a basic body strategy to sacrifice extremities to protect head and torso; cold hands and feet are a sign that you’re beginning to pull your blood into your center. This applies anywhere in the house, but particularly in bed. If your feet stay cold despite being under covers, you are probably leaking energy out of the top of your head. Given our recent fossil-fuel energy joyride, no wonder nightcaps are considered quaint!

It’s a US vs UK thing. Over there, the colloquialism is “could care less”. Over here, it is “couldn’t care less”. So anyone here saying “could care less” is (a) talking funny, and (b) importing the speech patterns of our neo-colonial masters. That’s why it grates so badly.

Sometimes I wonder how my ancestors survived. Being 1/8 Swedish, 1/8 Irish and 3/4 British I come from a line of northerners but I am definitely not built for cold. Without modern clothing I’d be pretty uncomfortable. I guess cavemen were tougher and put up with more discomfort. I also believe your body automatically changes to accommodate your environment, which is one reason why so many people today seem wimpy — because we have lived in such a cushy environment. There’s something to be said for just sucking it up and dealing with discomfort. As they say, it makes you a stronger person.

I was surprised by how many kW-hr it takes to heat your different houses. Considering that I use about 10 kW-hr a day to charge my Leaf EV, that’s not actually too much of a draw and shows that adoption of EV’s could be handled with overall energy conservation, although electricity is a different energy form than natural gas.

Where my mom lives they don’t have natural gas so she uses an electric base heater for low temps and then a wood fireplace. Wood is a nice carbon-neutral source of heat (except for the FF’s needed to transport it, and assuming it didn’t come from permanent deforestation). I’d also like to see what kind of a Stirling Engine could be built to convert some of that wood derived heat into electricity to charge battery banks on cold / snowy winter days when solar panels aren’t producing electricity. Of course it could be built, but it has to be cost competitive. At some point in the future it will be when FF’s run out, but that may be a while…

This is a good example of why we should try to conserve big chunks of energy. It frees up resources for other important uses. Adding electrified transportation the existing generation capacity is a very difficult prospect. But big cuts in “normal” use can make room.

Mark, 2 things about “ancestors”.

1-They were not wearing the clothes that we wear today. Look at historically accurate movies and they have these dead skins on them with the fur. I bought a shearling (sheep with the fur inside) coat a few years ago and I have to say it is the warmest thing I have ever own. I can walk around Chicago in dead of winter with just a cotton shirt on underneath.

2-If you have ever been backpacking (living out doors for days on end) then you will notice that your body does adapt to the cold. Also dressing in the proper layers/clothes helps too. I was surprised the first time I did this in 30-40F(-1 to 4C) weather and had a warm core the entire time.

Thank you for this!

We live rurally, and heat with wood (while also cooking with it)–and manage a woodlot in order to do so. But that doesn’t alter the fact that we *do* keep the house fairly warm (within “standard parameters” for “room temperature,” if you like). The reason for this is that we live in a very wet climate (Vancouver Island). It’s not cold, particularly, in the winter–but we worry about dampness and the consequent deterioration of wood, gypsum/wallboard, etc. And, of course, the mold.

I’d appreciate any thoughts . . .

San Diego can be quite damp in the winter. Mold is a serious problem here, so there is more to saving energy than simply shutting off the heat and toughing it out!

Thanks Tom for another great post. A great article relevant to the conversation is: Insulation: First the body, then the home. http://www.lowtechmagazine.com/2011/02/body-insulation-thermal-underwear.html

Tom, Thanks again for promoting individual actions.

We’re trying to reduce by using electric blankets, opening the blinds to let the sunlight blast in, etc, but in this uninsulated “cabin” in Big Bear Ca, whatever we do quickly wants us to “do more”!

However, when we lived in a multi residence apartment in Haines Ak, I noticed it was “too hot for Alaska”. The people next to us must have thought it necessary to make it feel like a California summer. So we enjoyed just slightly below average “perfect warmth” in our “unit” with barely turning the heater on. The neighbors didn’t seem to care even after I told them that my not using the heater might affect them as well.

These are the beginnings of hope, afterall, for the collective future!

This post strikes near and dear to my heart- I’ve been working on identical issues for years, though I’ve never gotten nearly so analytical, due to lack of equipment.

This may interest you- the heat loss of my house as a whole is about 115W/degC (your calculation, from last week’s post.) A few years ago, I did a very thorough (though not overboard) job of insulating and air sealing some of the rooms, including my bedroom. This approx. 200sq ft room now has a heat loss of about 13W/deg C. I installed no heat whatsoever in this room nor any of the others I re-furbed. With this heat loss, and with the body heat of two humans and two dogs, the room will actually gain in temperature on all but the very coldest of nights (say, below -10C).

The sad thing is that this degree of improvement would cost very little in initial construction costs, yet is mandated by very few building codes, and is used by very few builders.

What hardware and software did you use to record the temperature measurements? I want to do the same in my home.

I used the iButton thermochrons from Maxim. I believe I have the DS1922L model (or maybe a mix of the L and T?) I use the onewire java application (from Maxim) to read out, then do all my analysis/plotting in Python using matplotlib.

I’ve taken the same angle on lowering heating and cooling costs. Here in Ottawa our temperatures are often 30 °C (86 °F) in summer.

I no longer use the AC at all in the summer, which has been helped by installing a white roof. Tom, your comment about solar gain through the roof along with windows is a widely held myth. The goal is to have your attic sufficiently ventilated to aim for the same temperatures there as outside, so ideally it shouldn’t be helping much in the winter. The white roof helps keep the roof from deteriorating in the summer sun as well as helping the ventilation do its thing at keeping the attic and house cool. Last summer the temperature in the kitchen did not rise above 24 °C (75 °F) even with quite a few days above 30 °C.

One fact that I only really worked out a few years ago is that heating costs a relatively fixed amount for each ° you raise (or save by lowering), regardless of the outside temperature. So in moderate climates like your’s there’s a big relative saving by enduring a colder inside temp or delaying turning it on in the fall. I starting turning the temp down each year to the point where I felt cold. That point is now at about 15 °C (60 °F) when I’m active, and about 12 °C (53 °F) at night. Last year the cost of gas used for heating was just $383, which doesn’t justify spending much (yet) on improvements.

A huge advantage to lowering temperatures inside for our cold climate here is that I often *remove* clothing to go outside on mild winter days to shovel snow from the driveway, adding just a hat and gloves. I also cycle year round and add a just a wind-breaker (and hat, gloves) to my inside clothes down to about -15 °C (5 °F). I think we’d also be a healthier lot and less susceptible to winter illness if these were the norm. As it is now, I overheat when I go inside somewhere else where they keep it at tropical levels (which we call ‘normal’) in winter.

Two things: first, the solar gain through the roof is more than a myth: I have data—showing gain in the attic even on cloudy days. In a perfect world of exquisite ventilation, I agree: the roof gain would be irrelevant. This is seldom the case (attic usually hotter than outside).

Second, I agree that driving your body from one temperature extreme to another can cause illness, so that a cooler inside temperature in winter may indeed be better for your health.

Leaving a frigid building (or car) and going out into the heat of a tropical clime or a Midwestern summer day feels far worse to me. My Mother too was positive it was worse for the health than a hot-inside to cold-outside transition.

Great post, and quite fun for a Swede to read. Naturally we are ahead of you regarding home heating. Gas is unheard of here and almost nobody uses oil anymore. The most common ways are heat pumps (mostly air or geo thermal), wood burning in a heater with a water tank (either logs or automatically with pellets) and district heating from plants burning biomass, waste, oil or what have you. Some houses built during cheap electric eras lack circulating water and are heated by electric radiators (Sweden’s electricity are mainly nuclear and hydro).

Also the houses are insulated properly, and with the outdoor temperatures in your graph (varying between 5 and 20 C – springtime!) I would also turn heating completely off, but indoor temperature would stay around 19 C – 21 C. If I feel a little cold I can throw a couple of logs in the living room stove.

I’m not bragging here, but rather enforcing your point that much can be done. For us Swedes there are certainly other areas where energy can be saved.

Ah, the Swedes. I envy your sensible ways.

Plus, a decent sauna – not the plastic atrocities here in the US – can account for a whole lot of temperature drops and changes. Two years in the draftiest holes of Ireland, and not a single cold or cough, all due to a decent sauna. Nearly suffocated when the neighbors chimney cracked and peat smoke came in from the heated building next door though…. heating *is* hazardous to your health.

We lived in SD for 6 years (2000-2006) and never used winter heating of any kind. It never even occurred to us to use it. Winters are lovely in SD; it’s the summers that are uncomfortable. We were also the only people in our neighbourhood to dry our washing on the line outside. We’re back in Australia now, where people are a little saner about energy use.

If by uncomfortable, you mean 27°C (80°F), then I agree, it can be brutal. Aside from the rare Santa-Ana flare-ups, it’s wonderfully pleasant in S.D. if you are within 10 km of the coast. For real data, San Diego scores 481 degree days of cooling (Celsius measure; compare to 591 for heating). Atlanta requires over twice as much cooling, for instance. Most houses in San Diego are equipped for heating, but most do not have air conditioning for cooling.

At the top of my sensibility list are the Swedish electric sources of 51% nuclear and 43% hydro to run those electric heat pumps, and then the sale of still ample excess power across the Baltic.

Aside from that, I don’t know where the Swedes are that frugal with energy, as they use more per capita than most everyone else in Europe. Still, corrected for climate perhaps they do quite well.

http://www.google.com/publicdata/explore?ds=d5bncppjof8f9_&ctype=l&strail=false&bcs=d&nselm=h&met_y=eg_use_pcap_kg_oe&scale_y=lin&ind_y=false&rdim=region&idim=region:ECA&idim=country:DNK:SWE:DEU:FRA:ESP:GBR:CZE:SVK:PRT&ifdim=region&tstart=-309297600000&tend=1300075200000

This post reminds me of the bit in David MacKay’s “Sustainable Energy Without the Hot Air”, where he mentions that “the average winter-time temperature in British houses in 1970 was 13 °C”: http://www.inference.phy.cam.ac.uk/withouthotair/c21/page_143.shtml

Now in 2012, I live in South Korea, where about 26°C seems to be considered warm enough in the winter (with outdoor temps around -5 to 5 degrees). We nearly didn’t use any heating gas at all this winter — our downstairs neighbors did it for us, and our apartment rarely was below 20 degrees.

Interesting article. I’ll definitely try this strategy next winter: keep people warm, not things.

However, I have a criticism I’d like to share. The gist of it is that though individual choices pertaining to behavior are ethically important and may even make a small but good impact, the bulk of energy consumption, waste production, water use, etc. is not within the scope of individual decision-making.

My suggestion is this: lets us not forget the political dimension of this problem. No change sufficient to avert a crisis can be achieved without the proper regulations, incentives and political vision.

Here is a small essay that conveys beautifully this lesson: http://www.orionmagazine.org/index.php/articles/article/4801/

Best,

S

See the discussion last week initiated by Pye. In short, political action (in a democracy) is a mirror of individual choice. If we are not willing to make changes on an individual basis, changing our values, we are naive to expect politicians to do it for us. Unpopular moves tend to find insufficient political support.

A question, purely for clarification: what fraction of the day are you and your wife at home and awake during the winter, and what are your activities like during that time? It is one thing to have the house heated to 16 degrees C or so and to be up and about, washing dishes, cooking, cleaning, or even watching television with a blanket wrapped around you. It’s another to sit in front of the computer for six hours writing.

I spent three winters (in a considerably colder climate than SD) working in an old state building with high thermal mass. In order to save money, state policy was changed to require turning off the heat over the weekend. By early Monday morning the temp would be in the 15-16 degree range, but because of the mass and nature of the heating system, it was Tuesday before the temp returned to the normal level. The building’s antique electric wiring was inadequate to support space heaters. Mondays became lost days, because by 10:00 or so the staff’s hands — despite working in hats and coats — were too cold to type accurately.

My wife works at home, typing much of the day. I do as well on weekends and some weekdays. A heating pad in the lap (30–40 W) does wonders (rest hands on it briefly). Also fingerless gloves help, and I have seen USB-driven heated gloves as well. Heat the thing that’s cold. Who cares whether the items in your desk drawers are warm!

We keep our place fairly cool in the winter, but I do heat my own office to 20 when I work at home. Sitting at a computer typing is not conducive to staying warm. Heating one room is still a lot cheaper than heating the whole house (and probably the only advantage to being stuck with electric resistance heat).

http://www.richsoil.com/electric-heat.jsp

This fellow manages it just fine, with a heated keyboard and mouse. Who knew such a thing existed?

All this is great, but both I and my wife are near 70 and not in great health. We keep the house at 76F during the winter because we can’t cope well with less.

The real answer is to leave our empty-nest house and go to an apartment, but family dynamics does not make that an option.

This is in response to Anna’s post above, but may be of interest to all. I live in Vancouver and keep my house around 10-16 degrees C through the winter (15 degrees in the rooms we’re heating results in about 10 degrees in the rooms we don’t). Due to high humidity (winter is the rainy season), this would result in serious levels of condensation on windows and mold/mildew growth if not for the fact that we accomplish much of our “heating” using a dehumidifier which we run nearly 24/7. Using a dehumidifier as a heater has two main advantages:

1. You can keep the house cooler without experiencing condensation.

2. A dehumidifier has a COP greater than 1. I’ve measured the electrical energy use of mine and calculated the additional heat output from the “enthalpy of vaporization” of the condensed water and found the COP to be around 1.5. So compared to an electric space heater, the dehumidifier costs about 2/3 as much to achieve the same deltaT.

If you heat with electric, point #2 makes this a no brainer. Even if you heat with gas, point #1 may still make it worthwhile. See http://www.iwilltry.org/b/heat-your-home-with-a-dehumidifier/ for details of my analysis.

Of course this only works if you live in an area with high humidity. Fortunately it’s also only necessary if you live in an area with high humidity.

My thoughts exactly, people need to man the hell up.

P.S. There is a typo in the second sentence of the second paragraph of ‘Coping Mechanisms’. You say you ‘could’ care less about the temperature of your pictures, knifes, etc, rather than ‘couldn’t’

If you didn’t have heating in Britain, your pipes would freeze and burst. Even if you had frost detectors to turn on the heating at point, without heating because of the high humidity things would get damp. But certainly if I lived in San Diego I wouldn’t have central heating. I’d probably have a fire for the occasional cold evening.

The Swedes are very lucky to have enough hydro to be 43% hydro. They will build no new nuclear reactors. They are going to use a lot more biomass, but they are fortunate to have the space and the climate to be able to have a lot more biomass. They are lucky to be a small population in a large location with a lot of sustainable resource.

I would not suggest abandoning heat in cold climates. Note that my calculations assumed a 12°C set-point. The pipes should survive.

12c is I think 55F — the pipes would survive, but it is too cold to play piano, do school work, knit, sew, cook, etc… for us. We have noticed that the temperature we can handle inside depends on the outside temp and the humidity. We have ALOT of rain, so when it is damp and raining, we need more heat than when it is dry outside. Also, on the rare occasion that we have had realy cold weather and snow then instead of rain, we actually can handle a colder house. So, even with hats, we need about 65F to get school/piano work done here in wet weather, 60F on weekends is fine. And, 60F is also fine if it is dry cold outside, like 30F and snow outside.

See my comment above. Use a dehumidifier. It’s more effective at heating than an electric space heater (COP ~ 1.5) and it will keep your home comfortable at lower temperatures.

I see a couple statements above that irk me a bit with regard to how “lucky” people are to live where they do.

“Tom is lucky to live in such a pleasant climate”

“The Swedes are very lucky to have enough hydro”

These are not examples of luck but of choice: Tom’s in the first case and that of a great many people in the second. It could rightly be argued that there are too many people in the world today for everyone to live in such “lucky” locations, but that again is a result of choice (that of our parents and their parents before them, etc), and when there were fewer people, many clearly still chose to live in less hospitable areas.

It is a denial of responsibility to suggest that you are unlucky to live where you do when you are free to leave if you choose.

I choose to live in Vancouver despite the higher cost of heating (not to mention real estate). A number of factors influence this choice, but it is a choice non-the-less and one that I make every single day. The simplest way, by far, that I could reduce my energy footprint would be to move, but I choose not to. Curse my luck.

Semantics.

I say Tom is lucky to live in such a pleasant climate – but it doesn’t necessarily follow that there aren’t things about living in San Diego that are also “unlucky”, or that I begrude him his choice to live there.

Right. For instance, San Diego is not a place that can support the few million who live here now off of its local lands. Rainfall is 10 inches (25 cm) per year, and what agriculture does exist in the area is irrigated from water/snow that falls on distant lands. Maybe this can continue indefinitely, but it is a vulnerability.

Appologies, Lucas. Point taken. It’s exactly semantics that I was addressing, though I did so poorly. There are many aspects of people’s lives that they feel they have no control over when in fact they do. Unfortunately, our language tends to encourage the very denial of responsbility that needs to be overcome if people are to change the way they live. I think the disctinction between choice and chance is one worth drawing attention to, so I do so whenever I can.

No worries.

I understand how you feel.

Besides, we might have been neighbours at one point.

I grew up in Abbotsford and spent some years living in Vancouver before taking up my current rural existence in NW Ontario.

Yeah, Tom has nice weather, but what is his water bill like?? They have to pump the Colorado river over the mountains to get to him. That has to cost more than the 2 miles of piping to my condo from Lake Michigan (live in Chicago).

Las Vegas, Phoenix and So Cal are all going to be fighting for access rights to the water of the Colorado river over the next decades. Granted So Cal could start to desalinate the Pac ocean if costs get high enough, but Phoenix and Las Vegas are hosed since they are in the fricking desert.