[An expanded treatment of some of this material appears in Chapter 3 of the Energy and Human Ambitions on a Finite Planet (free) textbook.]

Sometimes considered a taboo subject, the issue of population runs as an undercurrent in virtually all discussions of modern challenges. Naturally, resource use, environmental pressures, climate change, food and water supply, and the health of the world’s fish and wildlife populations would all be non-issues if Earth enjoyed a human population of 100 million or less.

The subject is taboo for a few reasons. The suggestion that a smaller number would be nice begs the question of who we should eliminate, and who gets to decide such things. Also, the vast majority of people bring children into the world, and perhaps feel a personal sting when it is implied that such actions are part of the problem. I myself come from a long line of breeders, and perhaps you do too.

Recently, participating in a panel discussion in front of a room full of physics educators, I made the simple statement that “surplus energy grows babies.” This is motivated by my recognition that population growth bent upwards when widespread use of coal ushered in the Industrial Revolution and bent again when fossil fuels entered global agriculture in a big way during the Green Revolution. These are really just facets of the broader Fossil Fuel Revolution. I was challenged by a member of the audience with the glaringly obvious statement that population growth rates subside in energy-rich nations—the so-called demographic transition. How do these sentiments square against one another?

So in the spirit of looking at the numbers, let’s explore in particular various connections between population and energy. In the process I will expose the United States, rather than Africa, for instance, as the real problem when it comes to population growth.

A Brief Look at Population History

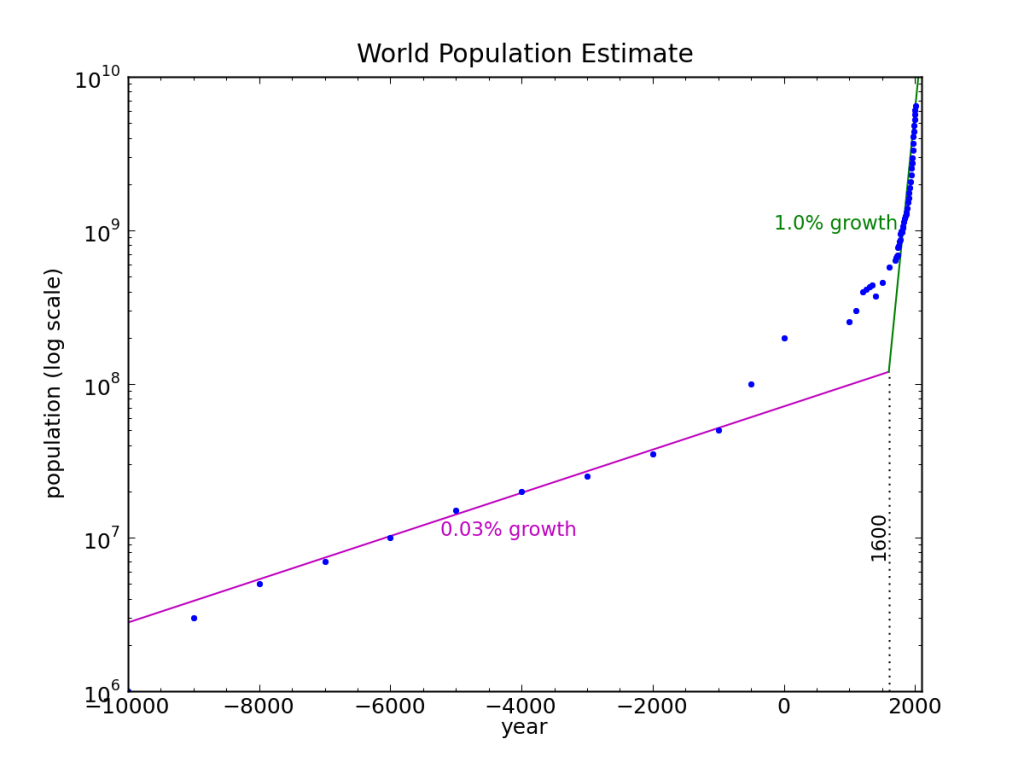

For many thousands of years following the end of the last Ice Age, human population rose steadily and slowly, at a rate of about 0.032% per year—translating into a leisurely doubling time of some 2000 years. About 3000 years ago, spreading agricultural practices led to a modest boost in growth rates. But the wild ride did not start in earnest until modern times.

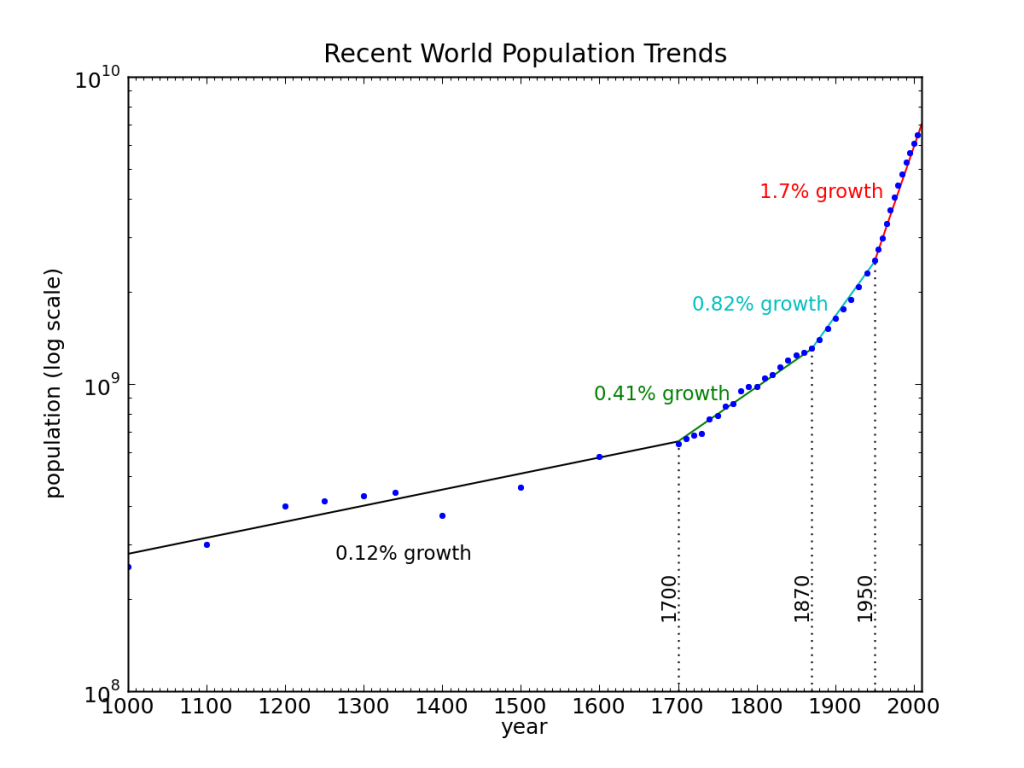

Lograithmic plot of historical world population, with two-segment exponential fit. Data from Wikipedia.

Even on a logarithmic plot—on which exponentials are tamed into straight lines—our population trend resembles the infamous “hockey stick” curve seen in so many domains (atmospheric CO2, global surface temperature, and practically any measure associated with human activity). A logarithmic hockey stick is truly scary. Because human impacts on the planet scale with population, it is not terribly surprising that a hockey-stick population curve should translate into hockey sticks everywhere. It is in this sense that population underlies nearly every issue and challenge of our times.

But what can we understand about population? What governs its rate? What accounts for the discontinuity in slope? Why did we leap into 1% growth and a 70 year doubling time in recent centuries?

One hint comes from a closer look at the recent history. Plotting global population in the last thousand years (below), we see a few breaks in the slope. For most of this period, we saw a modest 0.12% growth rate, amounting to a 600 year doubling time. Around 1700, the rate stepped up to 0.41%, doubling every 170 years. The next break happens around 1870, jumping to 0.82% and 85 years to double. Then around 1950, we see another factor-of-two rate jump to 1.7% and an impressively short 40 year doubling time.

We can perhaps attribute the 1700 jump to the Renaissance and scientific progress. We learned to wash our hands after wrestling with our pigs, and that diseases were not caused by bad vapors conjured by impure thoughts. The jump around 1870 corresponds to the Industrial Revolution, in which coal transformed the production of steel (providing agricultural tools), rail transport of commodities, and began to mechanize agriculture in a limited way. 1950 marks the Green Revolution: full-scale petrolification of agriculture, accompanied by massive fertilizer campaigns using natural gas as the chemical feedstock.

This leads to a rather simple thesis: the surplus energy presented to us by fossil fuels allowed us to feed people more easily the world over. The bounty of fossil-fuel-turned-food encouraged an explosion in birth rates, as happens for virtually all organisms given similar circumstances. It’s so blindingly obvious that I am embarrassed to have belabored the point as long as I have.

Does Energy Grow Babies?

Surplus energy grows babies. That was my statement to the audience, based on the dots I connected above. So what about the astute comment that countries with the largest excesses display the weakest—and even negative—population growth rates? This statement also rings true, so how can we hold both thoughts in the head?

Before digging into data, I’ll share my intuitive response. Developing countries are recipients of food, medicine, and manufactured goods from the industrial nations of the world. Surplus energy “here” can grow babies “there.” Such redistribution seems plausible, in any case. But why energy rich nations slow down was less obvious to me, aside from increased education and greater autonomy of women.

Dump Truck of Data

Clear some space, because I’m about to back up a truck full of data and dump it on your lap. Mostly, it comes from the International Energy Agency’s Key World Energy Statistics, 2012. Ten pages in this publication contain tabular data on the world’s energy appetite, along with population, GDP, and CO2 emissions. A little cut-and-paste, editor magic, and Python parsing can turn this into a truckload of graphs. I added data on population growth rates, mostly from the CIA statistics. Spooky, yes, but these were the most up-to-date numbers on the Wikipedia page.

The IEA table includes 139 countries, but also aggregates several key groupings of countries in the world. Besides giving figures for the whole world, the seven groupings include:

- OECD (the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development) includes the countries: Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Chile, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, Korea, Luxembourg, Mexico, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, Portugal,the Slovak Republic, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, the United Kingdom and the United States.

- The Middle East includes: Bahrain, Islamic Republic of Iran, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Syrian Arab Republic, United Arab Emirates and Yemen.

- Non-OECD Europe and Eurasia includes: Albania, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Georgia, Gibraltar, Kazakhstan, Kosovo, Kyrgyzstan, Latvia, Lithuania, the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, Malta, Republic of Moldova, Montenegro, Romania, Russian Federation, Serbia, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Ukraine and Uzbekistan.

- China includes mainland China and Hong Kong.

- Asia includes: Bangladesh, Brunei Darussalam, Cambodia, Chinese Taipei, India, Indonesia, Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, Malaysia, Mongolia, Myanmar, Nepal, Pakistan, Philippines, Singapore, Sri Lanka, Thailand, Vietnam and Other Asia.

- Non-OECD Americas captures: Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, Jamaica, Netherlands Antilles, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Trinidad and Tobago, Uruguay, Venezuela and Other Non-OECD Americas.

- Africa membership is self-evident.

Graph legends, in order to remain compact, leave off some of the qualifiers in the above list. Also, peripheral dots for individual countries are labeled in the graphs by an automated process. I did not make special effort to clean up unfortunate collisions between labels. I should also preface with a statement that the whole set of graphs to follow are not necessarily central to my main point. But I imagine they will be as interesting to many of you as they were to me, so why not make it an extravaganza?

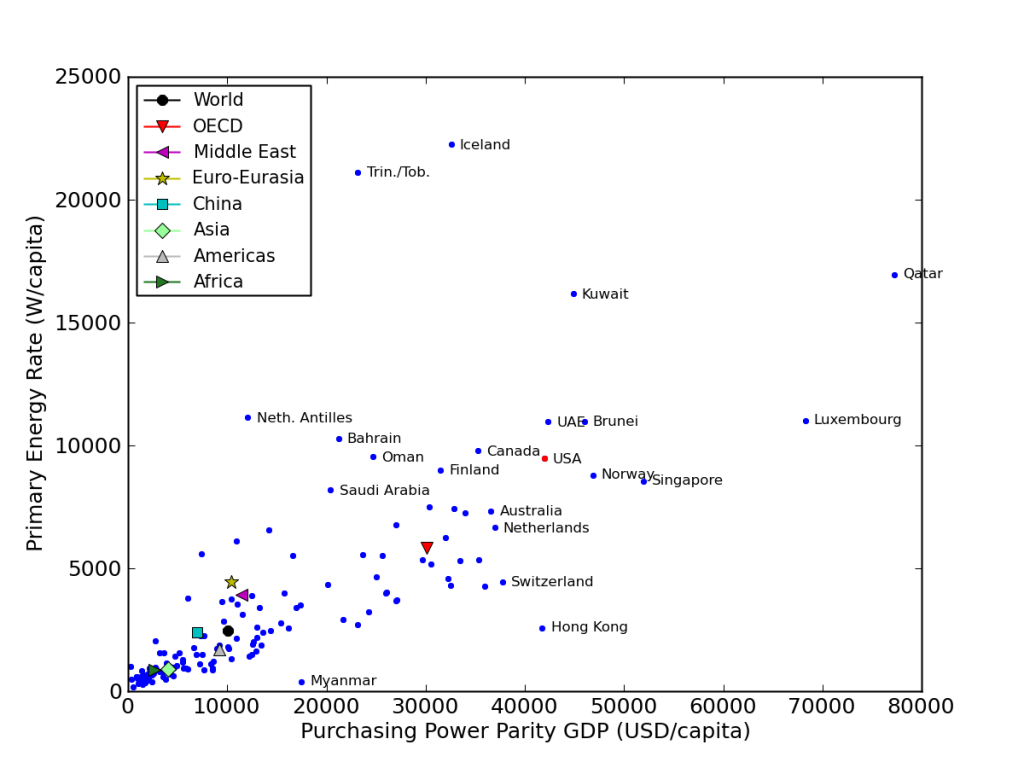

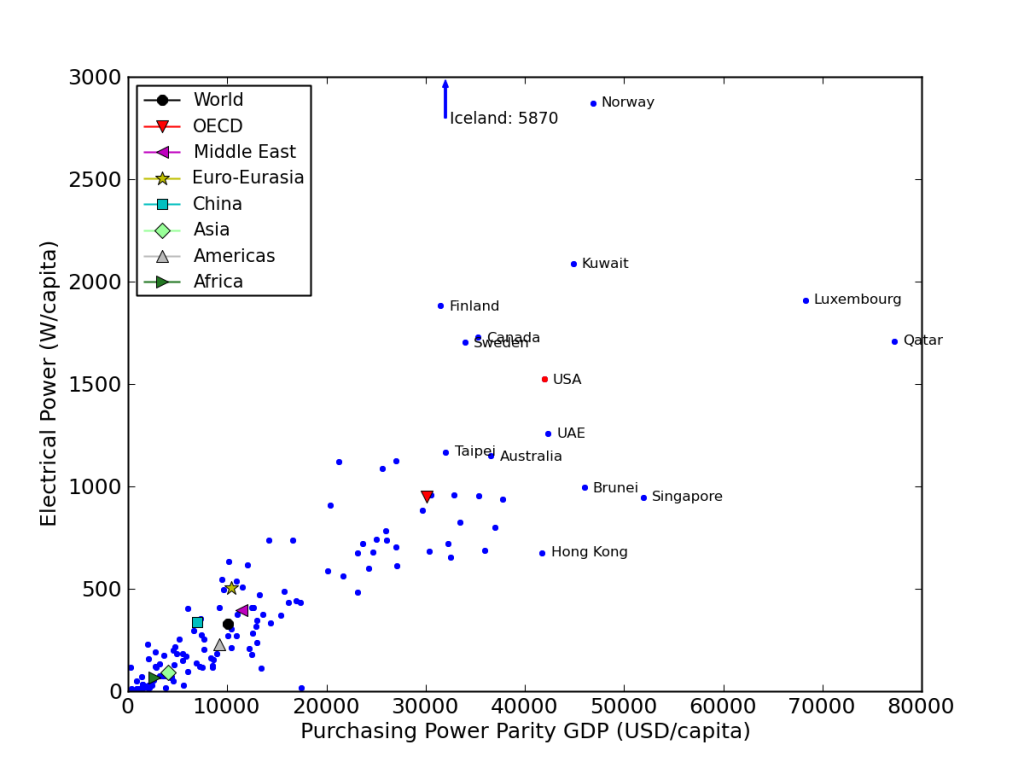

Let’s start with a look at a familiar plot of energy as a function of income (click to expand).

Rate of energy usage as a function of income for the world’s countries. Data from the IEA 2012 report.

I am using the purchasing power parity (PPP) flavor of GDP (gross domestic product), intended to put everyone on the same footing for meaningful income comparisons. I have converted the yearly per-capita energy into a power (Watts)—because that’s my favorite unit, and it gets away from “tons of oil equivalent,” as the original data are expressed. The trend is not at all surprising here: inhabitants of wealthy countries enjoy a greater rate of energy use, on average. Outliers are always interesting and instructive. The U.S. (always represented by a red dot on these plots) pushes well out from the pack in both dimensions, but not in an extreme way—ranking twelfth in total power per person and eighth in wealth. Some may recall from earlier posts the rule-of-thumb that Americans each run about 10 kW of power, equivalent to roughly 100 metabolic human (slave) equivalents.

Since it’s in the table, let’s look at what happens if we restrict our attention to energy in the form of electricity. Iceland was so outrageously high (about double the runner-up Norway) that I had to rescale the plot and indicate Iceland’s stratospheric datapoint. The U.S. ranks ninth in per-capita electricity usage. Note that the statistic is for delivered electrical power. The primary energy required to generate and deliver the electricity might run up to three times higher than the delivered rate, owing to typical 30–40% conversion efficiencies in power plants. For the U.S., electricity accounts for about 40% of primary energy, not 15% as a direct comparison of the previous two graphs might imply.

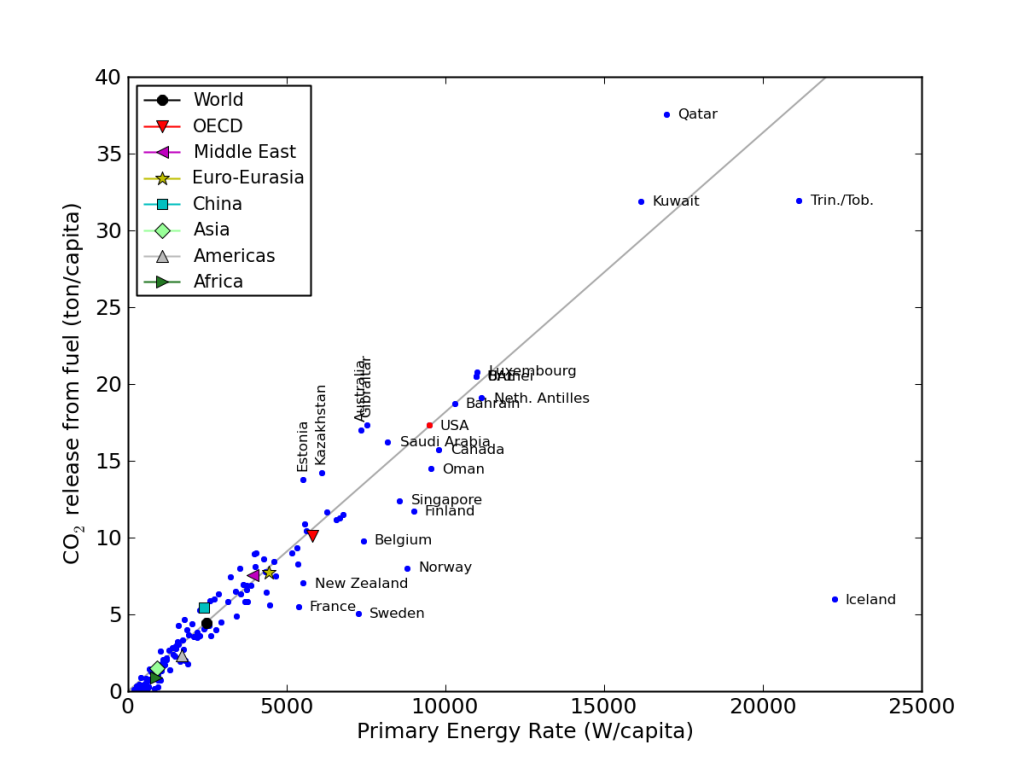

Before we circle back to population statistics, let’s take a look at how CO2 emissions stack up among the nations of the world.

Most fundamental is the carbon intensity of energy production. Basic chemistry suggests that each gram of fossil fuel creates three grams of CO2 and delivers about 10 kcal, or 41840 J of energy. Running 10000 W for a year (3.155×107 seconds) should therefore require 7.5 tons of fossil fuel, generating about 22 t of CO2. The graph above shows the typical U.S. citizen coming in at about 17.5 t of CO2 per year. This is short of our crude estimate because nuclear, hydroelectric, biomass, and other renewables account for almost 20% of the total energy, incurring effectively no carbon penalty (also, the U.S. comes in a little shy of 10 kW). Countries below the principal trend line have lower carbon intensities than the U.S. (1.82 t/yr per 1 kW of energy rate). Iceland is notable, getting abundant electrical power from geothermal sources.

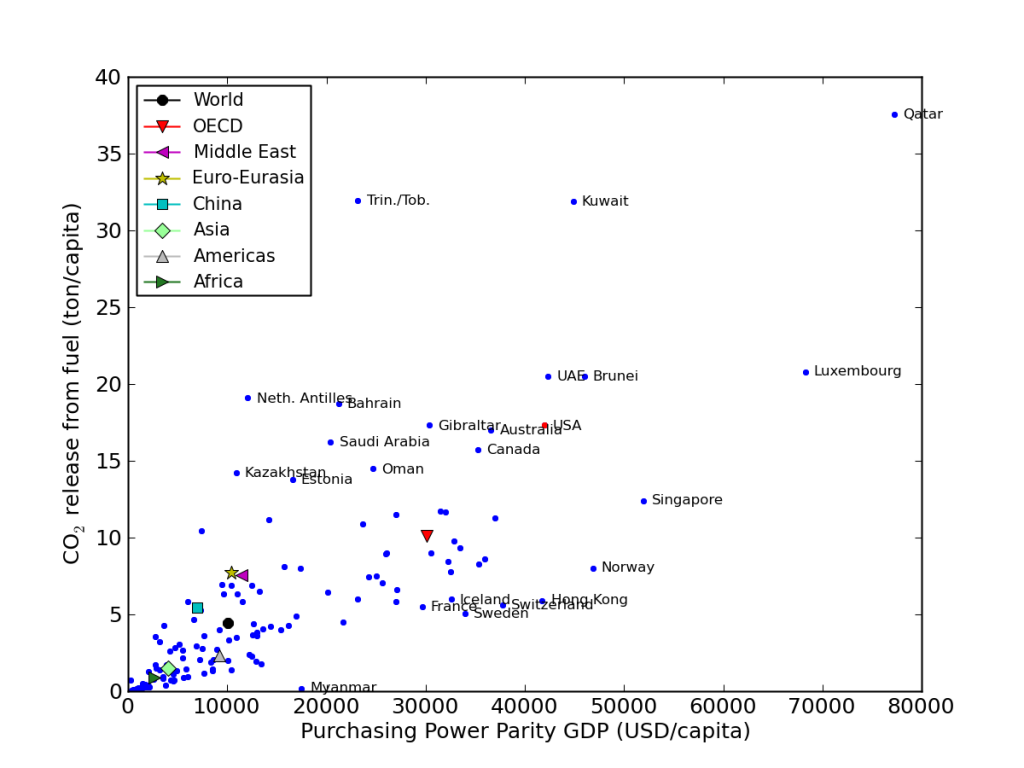

Now we pull income back into the mix to see how CO2 emission correlates to wealth. European OECD countries tend to appear on the “good” side of the correlation, while the Middle East tends to perform poorly by this measure.

Population Preview

Looking at the above graphs, we can learn something important about adding people to the planet. Adding a person in Africa has very little impact on energy use and (therefore) CO2 emissions compared to adding a person to the U.S., by a factor of 20. Picture an American baby 20 times bigger than an African baby. A Quatari towers 45 times higher than a typical African citizen when it comes to CO2. If one is inclined to think about where to limit population growth, the countries high on these graphs have their necks sticking out. Just sayin’.

Population Growth Correlations

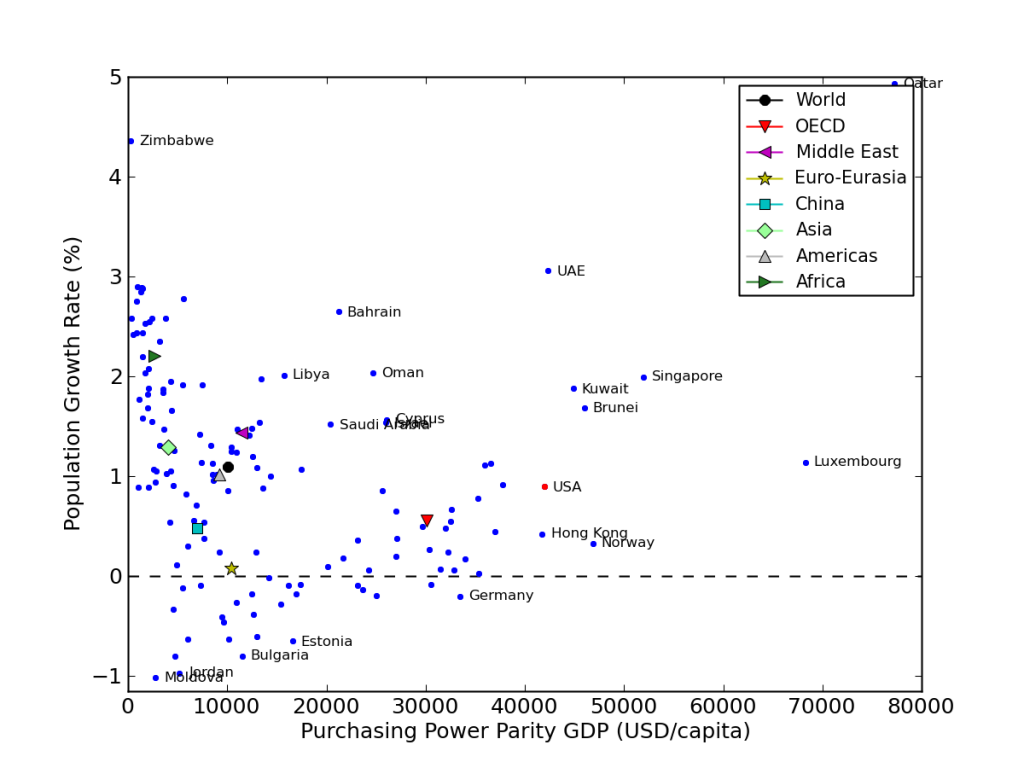

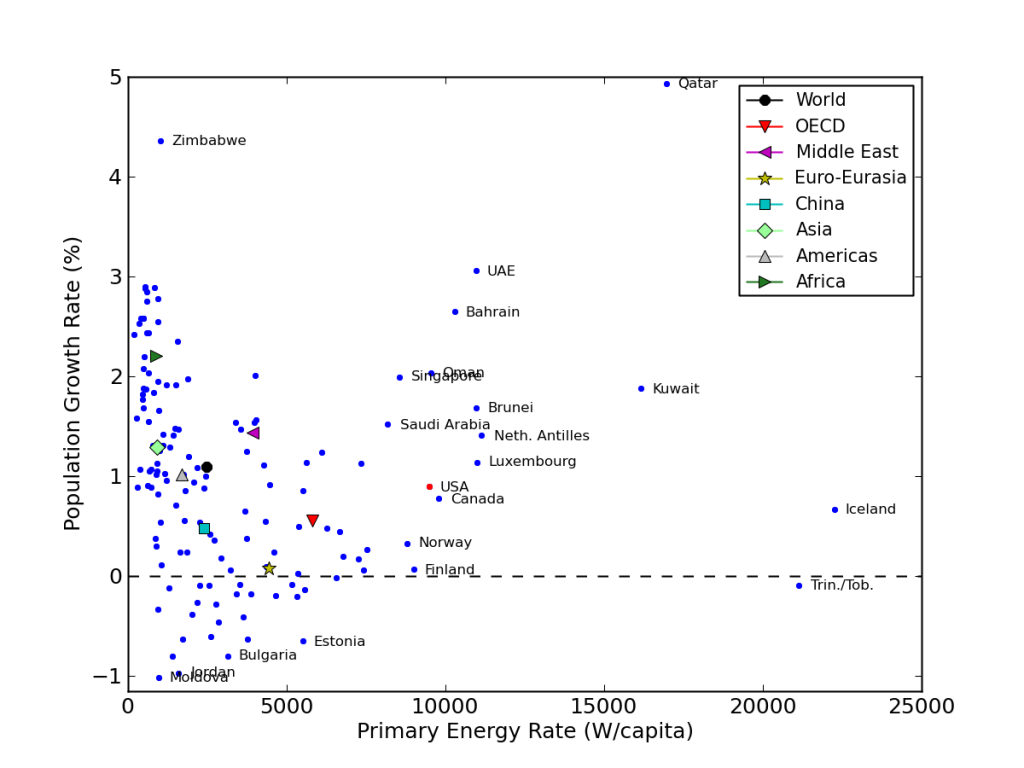

So far, we’ve only looked at metrics present in the IEA Key World Energy Statistics publication. Now let’s add population growth rate and see how things stack up.

First is the growth rate against average income. We have a clear correlation at the left edge: poorer countries have high growth rates, but rapidly dive to lower—and even negative—rates by about the time average earnings reach a quarter of those in the U.S. Then a funny thing happens: the cluster turns up again! This narrative-busting truth made me sit up straight, I’ll tell you. I fully expected a more-or-less smooth and gradual transition: rich means fewer offspring, according to the demographic transition idea. Granted, immigration plays a role here. It certainly is responsible for growth in the U.S. population. But it would be hard to convince me that the wholly lopsided statistics at higher incomes are all about immigration. Where are the rich nations with negative growth? After Germany, the negative growth countries are not to be found. Note that peeking out from behind the legend is Quatar, standing in open defiance of the “wealth reduces growth” mantra—boasting superlatives in both growth and income simultaneously.

Maybe this shouldn’t be too surprising from the perspective that economic powerhouses are dependent on growth, and a flagging population is a recipe for recession. A key ingredient for guaranteeing a bigger future is more working young people: in addition to providing labor, the growing youth enables pension systems and health insurance to function. Indeed, Germany is trying to battle its population decline, which imperils economic competitiveness. When I saw this article in the NYT, I lamented that the policy of protecting economic growth enslaves us to produce more children. I would rather humankind be the master of the economy, rather than the other way around. A quote from the article:

There is perhaps nowhere better than the German countryside to see the dawning impact of Europe’s plunge in fertility rates over the decades, a problem that has frightening implications for the economy and the psyche of the Continent.

How about the energy correlation, which I find more intrinsically interesting?

Naturally, the existing correlation between energy and income sets us up to see a similar pattern emerge. And indeed we again see the fertility trough appear at modest energy rates. Aside from Trinidad and Tobago, no country with an energy usage rate higher than 7 kW cares to join the negative-growth club. If anything, I find this graph more compelling than the previous one: the U-shaped sweep is more apparent. Again, it is difficult to argue that increased availability of energy dials down the baby spigot.

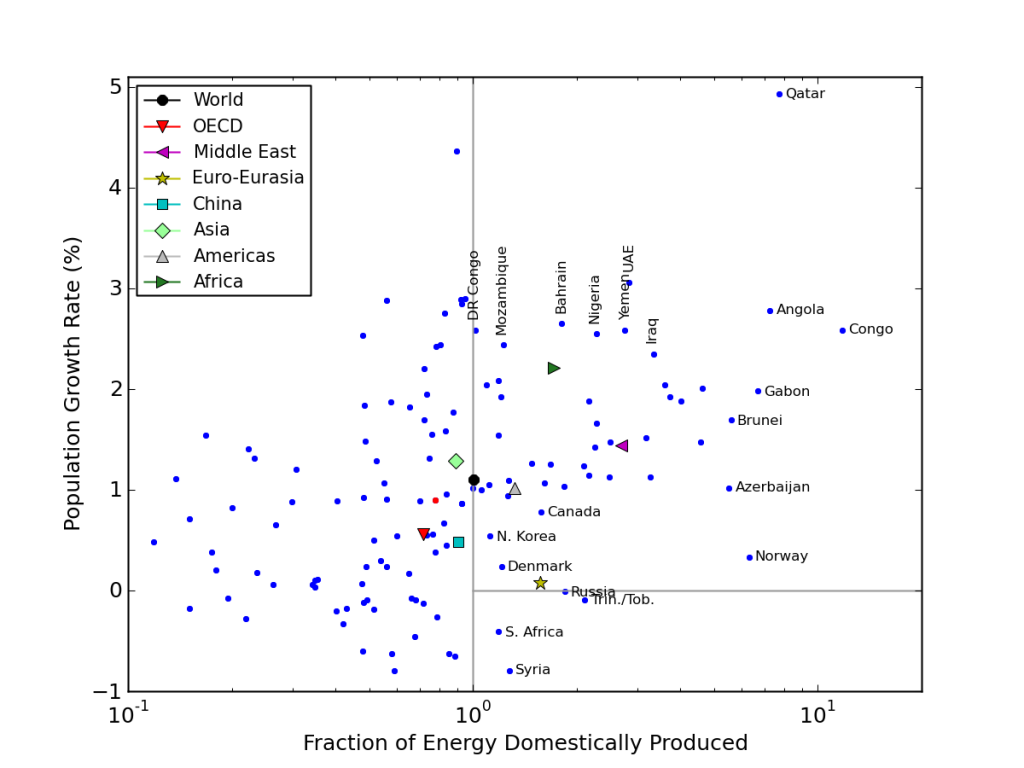

And finally comes a plot that I found to be rather striking. The IEA statistics include measures of total energy production, consumption, and net imports/exports. So I looked at growth rate as a function of the fraction of a nation’s energy consumption that it produces.

Population growth rates as a function of fractional energy produced by the country or region. Energy exporters are to the right of the vertical line.

I had to put the horizontal axis on a logarithmic scale to spread the points out reasonably. Many countries are cut off on the left-hand side (less than one-tenth of their energy consumption is domestically produced), but all net energy exporters are represented. We see that countries with surplus energy (the exporters) tend to be growers of population as well. To the left of the parity line (100 = 1 means balanced production and consumption), countries are far more likely to have lower or negative growth rates. Looking at the aggregate data points (colored shapes) perhaps reveals the correlation more strongly. Surplus energy tends to lead to surplus people, in our real world.

Collecting Thoughts

This is a complex topic. To do a thorough job I would have to disentangle immigration from domestic birthrates. But certainly the graphs above cast doubt on the intuitive story that nations rich in energy or money trend toward lower growth rates.

Why the U-shape tendency? The rapid downward slope is very likely due to improvements in education as nations have greater access to resources. Particularly important is the education of young women. Want to cut back on out-of-control pregnancy rates? Give the girls books. It’s much more than just educating women about birth control and reproduction, etc. Education empowers women to take jobs and make free choices. Lacking this, imported food financed by governments of industrial nations and by charities allows surplus to cross borders and provide the feedstock for new babies.

It makes me question the global benefit of increasing population by providing food assistance. I once contributed to such funds, but now find myself confused: what’s the plan, here? I get the humanitarian urge to support starving populations—really. This universal sympathy is part of human nature, but may become one of the forces that binds us to the railroad tracks leading to overpopulation and eventual collapse. That’s my concern. By supporting starving populations now, are we only doubling down so that the number of ultimate sufferers is larger? Is the bad news inevitable? Until I have a clearer picture, I’m somewhat paralyzed in my intrinsic desire to offer support.

In any case, it is easy enough to find reasons why the growth rate should plummet as energy/wealth break free from the bottom of the barrel. But why the reversal? One way to answer is to ask: why did the U.S. experience a baby boom after World War II? Significantly, the U.S. dominated oil production in this period: we were to the world then what the Middle East is now. Times were swell. We were full of hope and optimism, and believed we could do anything. That’s good baby-making weather, folks. We make decisions about what we can afford to support based on current conditions and some sense of the brightness of the future. Energy surplus, combined with a primal instinct for passing our genes and raising families, sets us up on a predictable path.

Where is the Real Population Problem?

We in the Western World tend to point the finger at developing countries as being the major culprit for population growth. And it is true that the fractional growth rates in such places is alarming, with doubling times of a few decades. We are justified in wondering how this population will be fed.

But we also saw that in terms of resource consumption, adding a Quatari is about 45 times worse than adding an average African. Adding a U.S. citizen is about 20 times worse. Yet what does it really matter how extravagant the life of an average Quatari, Kuwaiti, Trinidad & Tobagan, or Luxembourgian is? These are small countries. Shouldn’t our concern land on places like India or China? Couple large populations with aggressive development, and these countries stand to change the global calculus rather dramatically.

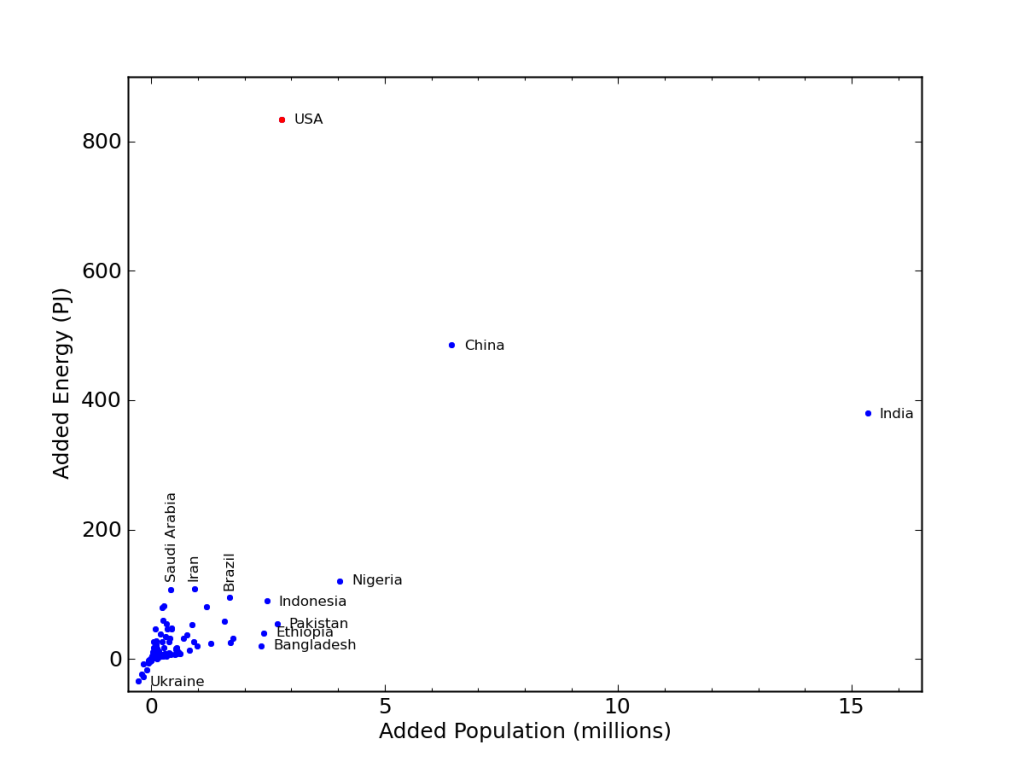

Given data on the population and growth rate, we easily compute the number of people added per year in each country. Now let’s assume that the added people share the average conditions of the nation as a whole. So we can multiply the number of people added by the national per-capita energy use to get a total amount of energy demand added to the planet because of population growth. Off to the graphs…

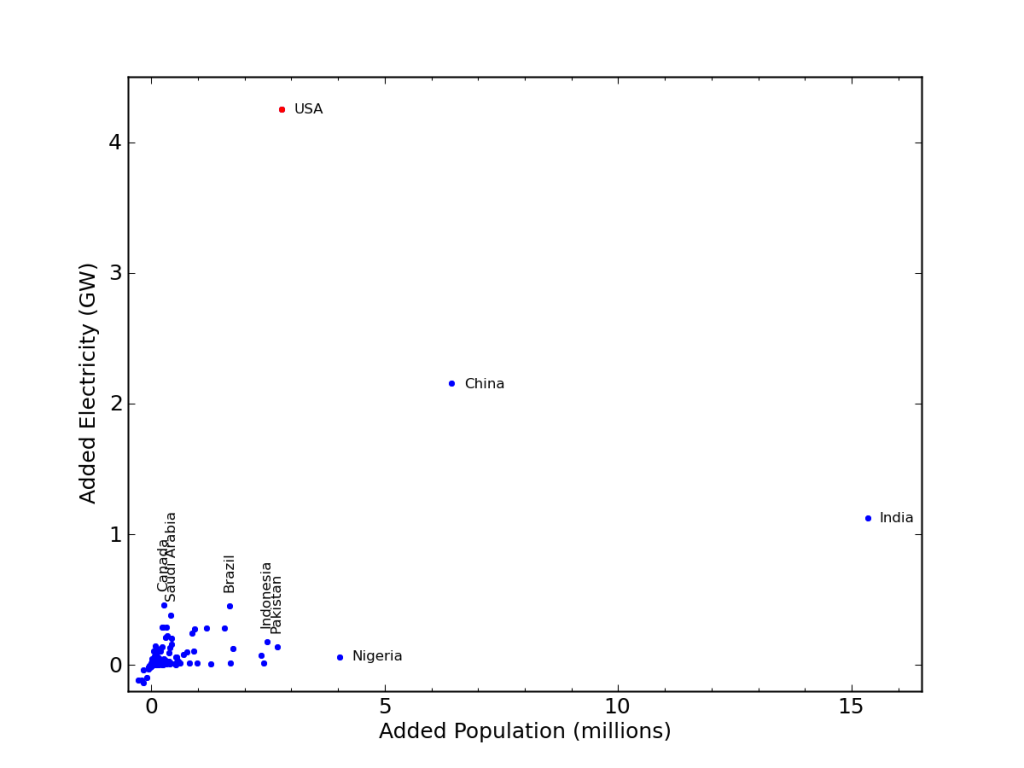

Annual absolute energy demand added as a result of population growth, as a function of the number of people added per year.

India adds about 15 million people per year (wow). China adds a little over 6 million. Nigeria is next, at about 4 million. Then we have the U.S., adding 3 million per year. But of those, the U.S. is the hungriest in energy terms. The graph shows how many petajoules (PJ) of demand are added each year per country due to population growth (other factors can also contribute to energy growth or decline; here we isolate the population portion). For reference, the entire world’s annual appetite is 530,000 PJ. What we see is that population growth in the U.S. is adding energy demand faster than any nation on Earth. China and India are also important (and in absolute terms they are certainly more important energy growers, due to a rapidly changing standard of living). But the answer to the question: who’s population growth is having the largest effect on global energy demand?—it’s the U.S.

One could easily argue that over the lifetimes of the newly added, ultimate energy additions due to China’s present population growth will outstrip those from America because of the changing standard of living. Firstly, it is not crystal clear how long the Chinese juggernaut will last against the unknown challenges of the future. But perhaps more important is that jostling for top position could obscure the glaring outcome evident in the graph. It’s the U.S., China, and India where population growth is driving global increase in resource demand—to the extent that energy is a proxy for generic resources. The rest of the world is of secondary importance on this score. Where is population growth putting the biggest squeeze on resources? It’s these three countries, with the U.S. presently well ahead of the others. Meanwhile, the Ukraine is doing the best job of removing demand from the world.

Annual electrical power capacity added as a result of population growth, as a function of the number of people added per year.

The electricity story is similar. Population growth in the U.S. is driving the addition of about 4 GW of annual electrical generation capacity. Again, China and India are on the map, with the rest of the world crowded into the lower-left corner.

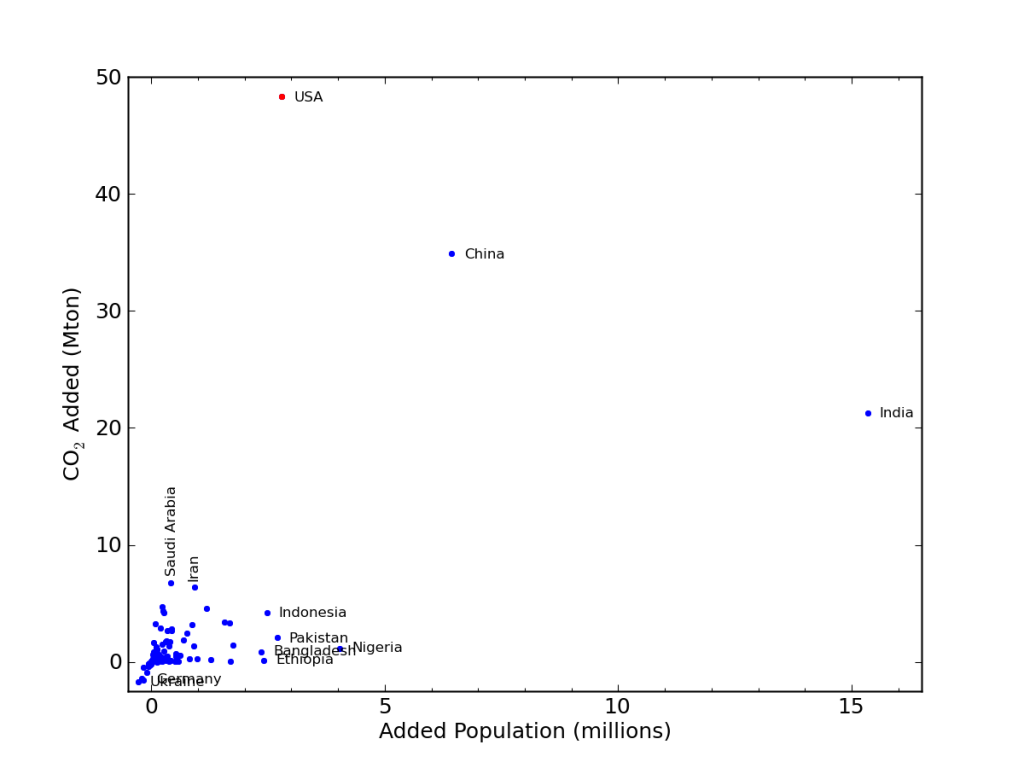

Annual absolute CO2 added as a result of population growth, as a function of the number of people added per year.

Something moderately interesting happens when we cast the plot in terms of CO2. Because India and China use “dirtier” energy sources, in terms of CO2, the gap between the U.S. and China/India is reduced. The U.S. still stays on top, but less overwhelmingly so. Some Middle-Eastern countries are straining to break away from the pack as well—but not in a good way.

Child Free by Choice

The list of reasons for why my wife and I decided not to have kids is long (not to say that we did not also see benefits). This post gets at one of the facets. Adding a child in the U.S. has a disproportionately large impact on global resources, whose finite nature is becoming increasingly apparent. At some level, ours is an attempt to arrest the innate human drive to reproduce (which I do share), because this results in adding more people to the planet—perhaps not the wisest course at present. Parents readily portray our choice as selfish—probably because we have more freedom in how we spend our time. But selfish arguments are destined to fail: virtually all choices humans make involve self-consideration, and therefore have a selfish component. Flipping the argument around, by not having kids, we deprive ourselves of: the undeniable joys of parenthood (mixed with occasional exasperation); potential caretakers as we age and lose facilities; and a genetic link to the future. In part, I forfeit these advantages because I have trouble justifying why my personal needs should come at an outsized cost to a unprecedentedly challenged civilization. In this way, I can just as easily cast the decision to have kids as the selfish choice. Not popular with the breeding sort: people don’t appreciate being labeled as selfish. I expect a few howls.

Oil-Clouded Crystal Ball

I try to be careful not to convey certainty about the future—which I note is not a behavior i often witness from optimists. Rather, I try to point out distinct possibilities that we collectively tend to ignore or deny. Only via increased awareness to neglected issues can I ever hope to be proven wrong in my concern. That would be a lovely outcome, and in fact is the whole point for me.

We are in the midst of an unplanned experiment of unprecedented scale. We have 7 billion people on the planet, growing at almost three new (net) people per second. It’s an uncontrolled mad dash into the future. One could imagine metaphorical scenarios of crashing into a brick wall or running off a cliff, exhausting ourselves and stopping to catch our breath, or leaping into space to leave the planet. I certainly have my guesses, but I can’t spell out an unwritten future.

I dredge back up the single-most important graphic that informs my world-view. We know that fossil fuels have far-and-away dominated the scale of our energy use, and that these are finite resources. We can therefore make the following plot with some confidence. I am especially confident about the big question mark in the future.

To the extent that surplus energy is responsible for the population boom, does the symmetry of the fossil fuel curve carry predictive power for population as well? These curves have been historically tied together. The burden of proof is on the optimists who presume that we can break the dependence. In a prior post, I emphasized the difficulties associated with breaking from this curve. Another post tabulates the relative superiority of fossil fuels over present-day alternatives, amplifying the challenge. It is not physically impossible, but supporting billions of people on this planet for the long haul is not something we are proving adept at doing. When the historical record is riddled with examples of civilizations peaking, overreaching, and collapsing, it becomes rather difficult to subscribe to the notion that this time is different, when faced with so many monumental and simultaneous challenges.

Population, as a reflection of human nature, may well be the mother of all challenges. Tightly bound to resource demands, the problem isn’t going to go away by ignoring our own personal roles and instead focusing attention on poor nations half-a-world away. Economic growth incentivizes population growth, which plays right into our biological desires. It would be refreshing to no longer be enslaved as victims to either of these forces. Otherwise we don’t really get to write our own future. And nature doesn’t care if we don’t understand.

Views: 8430

What about having just one child? That still brings medium and long-term population reduction, while allowing you to enjoy parenthood. For example, me and my girlfriend are both lone children, if we also have only one child, in the span of a two generations we would have one person in the stead of four, a pretty dramatic reduction rate.

No doubt this is an improvement, and drives reduction, which is great. Consider, though, that this one child, if born in a high-energy-consumption country, will be a monster consumer added to the planet. There are no great solutions here—such is the mess we’re in.

It is also worth adding that China supported a one-child policy for many years. This action did not produce dramatic results (like halving population), while being extremely unpopular and causing untold number of atrocities. It’s a very nice personal choice, for the few willing to do so.

What, this isn’t dramatic enough for you? http://www.china-profile.com/data/fig_WPP2010_TotPop_Prob.htm

The full effects of the policy haven’t been felt yet because the people who were children when it was instituted have seen a dramatic increase in life-expectancy. In the next couple years the true effects will be seen, a crest like what’s predicted is absolutely unprecedented and may well have a very positive effect on the outcome of all these crises.

Fair enough: demographic inertia is a powerful force left out of my “right now” plots. More often than not, it works the other direction: lowering fertility to replacement rates still sees population grow for decades to come. Autocracies can bend the normal rules.

How is that “the other direction”? Birth rates are below replacement in most of the rich and much of the poor world. In only a few countries has that translated to declining populations yet.

China’s only unusual in having had such a coercive policy, and I’ve seen people question whether that even had much effect. Its TFR is low but it’s like #154 out of 200 or so; dozens of countries have lower TFR without one-child policies, whether rich ones like Switzerland or poor ones like Bulgaria.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_sovereign_states_and_dependent_territories_by_fertility_rate

Tom,

I think sometimes that one reason some narratives we take for granted as being “truth” don’t actually seem to line up with reality is that they are based on widely disseminated, out of date information that was generally accepted as “truth” at some point in the past.

At some point, it was standard school curriculum to teach that birth rates decrease with affluence – that may have been true to a point, but the world is obviously a rapidly changing place.

Of all those people that learned x, y or z in school, how many continued to update their “picture” after they left school by keeping up with all the latest developments in fields related to x, y or z?

I also meant to say:

Keep up the good work with the “narrative busting”.

No, it’s still true that birth rates decline with affluence among nations. Tom didn’t give any graphs of birth rate, he gave graphs of population growth. There’s a demographic intertia effect. Outside of the Arab-oil states, most of those rich countries are on track for population decline, they’re just not there yet.

As for the bottom of the U, where countries are shrinking, that’s in large part because people are actively emigrating away from bad economies. Particularly for Eastern Europe; don’t know about Jordan, which seems to be bad data: Google “Jordan population growth” gives 2.2%, not -1%. The bottom of the U might snarked as “just (energy?) rich enough to leave for somewhere richer.”

Other notes: the climate importance of hydro, geo, and nuclear power is pretty obvious. Only one of those is expandable.

Perhaps also important: the importance of local climate. Hong Kong is rich while low in energy use, but it’s also subtropical if not tropical in climate; they certainly don’t need any heating fuel the way Nordic countries, Canada, or the northeast US do! And relatively even day lenghts, vs. long winter nights, so cutting down on artificial light for what that’s worth. Though Hong Kong’s also very dense with good public transit. Cold sprawling countries are going to burn a lot.

(Glaeser argued that the best thing the US could do for the climate would be to move into super-Manhattans along the California coast. Shame about the redwoods, but energy use for transportation and climate control would drop precipitously, compared to car and A/C sprawl in Texas.)

Damien RS,

Ah, fair enough – my mistake.

That’s what I get for posting in a hurry.

Although I stand by the larger point that I was trying to make, ie, that many of the narratives that are generally accepted as being “truth” (and that may have even at one point been true) can often be demonstrably false, yet they persist regardless.

Population growth rate is a useful, but problematic value to look at to evaluate the ‘surplus energy grows babies’ thesis. A big part of population growth rates in these areas will be due to extensions in life expectancy (as well as immigration, as mentioned). How do the correlations between energy usage and total fertility rate look? (https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/rankorder/2127rank.html). Replacement rate (zero world population growth presuming stable life expectancy) is going to be some value a bit above 2 (demographers use a short-hand of 2.1, although one can quibble with it).

“The bounty of fossil-fuel-turned-food encouraged an explosion in birth rates ..” Any proof for this claim? My understanding is that birth rates were always high, but industrialization enabled reduced mortality and therefore higher population levels. You seem to suggest that people decided to have more babies instead. Overall I have a feeling that this was one of your less well thought out posts. As mortality is reduced population increases, but people have adapted to this by reducing the number of babies they have. . This has been especialIy clear in places where environment has made such decisions possible/attractive (cities, economic growth, education, role of women, green revolution etc.) We have a one-off population increase going on with population settling to around 9 billion. In many wealthy nations population will decline. I warmly recommend Fred Pearce’s “The Coming Population Crash: and Our Planet’s Surprising Future”.

A fair point. How much control people have over the number of children they end up with varies a lot from person to person, I suspect. Some families do make decisions, and some of those will be tied to resource availability, I expect. Food availability is also important to survival, whether or not decisions are involved. And there is no doubt that fossil fuels extended our ability to grow food dramatically, supporting larger populations. I could be wrong, but the correlation is remarkable, and there is a clear line of causation involving food.

A wonderful source of statistics and visualization off all sorts of things including some of the data here is gapminder.org

As a demonstration: http://www.bit.ly/1a3Ii2X

On the x-axis we have per capita energy use on the y-axis the fertiliy level. Color indicates life expectancy and the size infant mortality. Good societies are redish small balls. As you can see, as time goes by fertility rates drop while per capita energy consumption tends to increase. While this is going on life expectancy increases and infant mortality declines.

(If the short link doesn’t work here is the long one http://www.gapminder.org/world/#$majorMode=chart$is;shi=t;ly=2003;lb=f;il=t;fs=11;al=30;stl=t;st=t;nsl=t;se=t$wst;tts=C$ts;sp=5.59290322580644;ti=2010$zpv;v=1$inc_x;mmid=XCOORDS;iid=0AkBd6lyS3EmpdHRmYjJWLVF0SjlQY1N5Vm9yU0xxaGc;by=ind$inc_y;mmid=YCOORDS;iid=phAwcNAVuyj0TAlJeCEzcGQ;by=ind$inc_s;uniValue=8.21;iid=0ArfEDsV3bBwCcGhBd2NOQVZ1eWowNVpSNjl1c3lRSWc;by=ind$inc_c;uniValue=255;gid=CATID0;iid=phAwcNAVuyj2tPLxKvvnNPA;by=ind$map_x;scale=lin;dataMin=-1.3096;dataMax=8.4$map_y;scale=lin;dataMin=1.009;dataMax=7.55$map_s;sma=49;smi=2.65$map_c;scale=lin$cd;bd=0$inds=)

Thanks for finding this—looks like a useful interactive tool. Definitely flatter at high energy use. But a slight U-shaped tendency remains (low point still about 1/4 of the way along the energy scale). The net effect of decreasing infant mortality and longer life expectancy obviously also contributes to population growth, and these advances would seem to be correlated to energy availability as well. Add immigration and the net effect is still that energy rich countries expand their population and put ever greater strains on resource use. Maybe a more generic statement is that surplus energy tends to grow population (by several mechanisms), which acts to accelerate the consumption of energy.

This is a fairer representation of the demographic transition, although the scale on the TFR axis doesn’t seem to appear correctly for me. Hovering over values displays values reasonably close to what other sources I have seen say they are.

The results as I am seeing them is that the only states which are above the replacement fertility line are petro-states with relatively low socioeconomic freedom (complicating factors already recognized by demographers). The remaining curve flattens out quite nicely into a TFR of ~1.6. This really does seem to blow the thesis out of the water.

China is well below replacement, but it has an aging population. India has a shrinking TFR, but if increased energy consumption is required to get them into negative territory, average energy use is going to have to double or triple. We also see by the difference in TFR and Pop. Growth how reducing new population isn’t going to work in the medium term to reduce total populations much.

It does tell us what demographers have been saying for a while, improve living conditions to some minimum threshold and make family planning services available and people will have fewer babies. If we are going to get through this without drastic human die-offs, we have to focus on dragging more people into the base of that L, meaning making the elements of happiness available for less energy.

From the gapminder graph it seems there is an energy per capita transition as well as a demographic transition, and it goes the wrong way.

Compare China and South Korea. SK without any coercion has a lower birth rate, but note that as SK gets around 1.7 children/woman, the birth rate declines very slowly thereafter, but the energy use rises steeply from 1.6 to 5.2 units per capita.

And China is going the same way. Energy per capita rising steeply as birth rate hits 1.7 children per woman and declines thereafter very slowly.

I think it’s consumeritis. “Have fewer kids, buy more stuff.” And it’s not good.

http://www.panearth.org shows how energy turned into food fuels population growth.

Before I forget, I will be extremely busy over the next little while, and often away from a computer for extended periods. Comments may go unapproved for a long time. I may get a substitute moderator to keep things flowing, but may not be able to give the comments any personal consideration. Sorry…

Wow. As usual, really interesting post!

Thanks for the friendly warning about all the data!

Going to take some time to chew over what you present here, but its good stuff!

Bottom line, I found it interesting your link to energy. I have always heard that money is not the end of the line, its all about energy. Our money moves around via computers, with no energy, there is no money flow.

Your ‘twist’ on energy ‘here’ is growth over ‘there’ is fascinating.

“…surplus energy tends to grow population (by several mechanisms)” I disagree. I think the issue is that fertility rate responds more sluggishly to technological changes than mortality rate and life expectancy. This means that people start with high fertility levels. Then with improved hygiene, food supply etc. mortality is reduced and life expectancy increases. The result is that population increases UNTIL the more slow fertility rate is adjusted to the lower level. I think this is what you see in the data (for example when you play with gapminder) Some arab countries have the combination of high fertility and high energy consumption, but they are outliers. Most of humanity is behaving differently. So we are not talking about permanent population increases made possible by energy consumption, but transient effect due to changes in society. This transient can be made shorter with sensible policies. This is I think also the main message from population experts (although they seem to disagree slightly on the final population size. 9-10 billion seems to be the right ballpark AFAIK.)

The guy behind gapminder.org (prof. Hans Rosling) has also very nice presentations in TED about these issues. Energy consumption can (and usually does) increase even as the fertility rates drop. Also increasing mortality is a very bad way of reducing population. Here is what happened in Ruanda. It took just few years to increase the population above the levels before the genocide http://www.google.fi/publicdata/explore?ds=d5bncppjof8f9_&met_y=sp_pop_totl&hl=en&dl=en&idim=country:RWA:BDI#!ctype=l&strail=false&bcs=d&nselm=h&met_y=sp_pop_totl&scale_y=lin&ind_y=false&rdim=region&idim=country:RWA&ifdim=region&hl=en_US&dl=en&ind=false

A few things that have to be pointed out:

1. It is correct that people rich countries have a much larger impact on the environment than people in poor countries. It is not correct to assume (I am not saying you do, but it has to be clearly pointed out) that this means there is no problem in poor countries. We usually evaluate impact in global terms such as CO2 emissions, but this is by no means the only way to wreck the environment – it can be very successfully wrecked locally by very poor people who hunt for bushmeat, use unsustainable subsistence farming practices and cut down their forests for firewood. See what happened in Haiti for one of the best examples. Most of the developing world is already or is soon going to be drastically overpopulated at present.

2. The reason for the demographic transition is not education. The hardwired evolutionary mandate is to increase inclusive fitness, not to increase the number of offspring you have. Those are not necessarily the same things and they certainly are not the same in humans. Keep in mind that humans are perhaps the only species that has grandparents contributing to raising the offspring. We (or at least most of us) tend to look farther into the future than the number of kids we have when it comes to inclusive fitness maximization and factor in such things as maximizing the quality of the offspring and its own chances of reproducing.

In a modern western society this translates into having to train your kinds well in the complex behavioral codes of such a society, ensure they get a good education and a well-paying job, etc. All of this is necessary because you want your kids to have the best chances of securing quality mates and reproducing themselves. But all of this takes enormous effort and resources in such a complex society, and combined with the fact that both parents have to go to work and earn the money to pay for all of that, it is easy to see why people can barely afford to have 2 kids, often even less than that. With the key word being “afford” – as paradoxically as it sounds, people in rich countries cannot afford to have as many children as people in a poor country can, because the cost of raising them does not scale linearly with GDP. In some cases it is indeed because people got educated and enlightened enough not to want more kids, but those are the minority. This is the explanation for the “demographic transition”. Also, very importantly, it applies to the middle class, not to the superrich, to the people that are so poor that they don’t care about such things as college education, to the people that are not very rich or very poor but who who highly desire fertility and don’t factor those things in their inclusive fitness maximization “calculation” either, usually for religious reasons. The Saudi royal family has ballooned to more than 10,000 members over the last 70-80 years and they did have all the money they needed and in later years the education too. But precisely because money is not a problem for them, and because of their religion, it has come to this.

“The hardwired evolutionary mandate is to increase inclusive fitness”

The only really hardwired mandates are “enjoy having sex” and “enjoy taking care of the children that result”. The rest is subject to human reason.

I’m not a neuroscientist, a psychologist or an anthropologist, but I would bet that the really hardwired one is “enjoy sex”. Childcare practices change too much across and within cultures, from extensive life-altering personal involvement through complete abandonment and/or delegation to other adults. There is, for sure, the “cuteness” empathic factor, but that’s not like a genetically hardwired enjoyment in childcare.

Those U-shaped curves of population growth are unexpected and astounding.

I wonder if they hold up in the past; was ~2,000 W/capita at the bottom of U in 1950 too? Is 2,000 W/capita some kind of universal aspect of human nature?

I could be wrong, but I suspect not a few people had access to 2kW/capita in 1950.

A lot of the visually U-shaped impact in the population growth vs. income curve comes from extremely small, rich, nations with high growth and income. These are not very important. I am quite curious about the nations “in the trough— would like to see which they are”. The labeled ones, like Bulgaria and Moldova, seem to be small to medium-sized eastern European nations.

I find that figure 530,000EJ total annual consumption is little bit off; are you sure about it? Exa = 10^18, 530,000EJ = 5.3*10^23J, divide that by 7 billion people, and number of seconds in a year (31536000 seconds), and you get average power needs of a human as 2.4 megawatts! Even if all of the 7 billion had the power consumption of 10kilowatts of average american, then, the total energy consumed in a year would be only 2208 EJ, not 530 000 EJ!!

Human diet: 10MJ per day -> 115 watts. Thou, food energy is obtained by consuming ten times more oil than joules produced as food, so, more like 1.15 kilowatts. Litre, or kilogram of fat / oil / gasoline has 40MJ of energy, but as conversion is so inefficient, you need 2.5 kilos of oil for your daily diet.

Recently I got into calculating these energy issues too, particularly about having a 10 000 km flight, and I found out, that it’s in the same order of magnitude as if driving that lenght by jet plane, car or even biking! Cause human calories are kinda costly, if the food consumed is produced by modern method. That flight consumes about 1000 kilograms of fuel, would take you about 400 days of biking, yet, you consume about 2.5 kilograms of fuel yourself, too.

My bad. I meant petajoules, and have corrected–thanks.

I think surplus energy grows babies till the saturation point caused by economic limitations such as cost of education,housing,…etc.

Tom, surely you understand your personal decision to not have children will have no effect on the trajectory of population growth. So, it merits neither criticism or praise. As K strategists, you also know that it’s pretty clear humans do indeed take the signals from resource constraints, which is why fertility rates are already guiding downwards. Fertility rates in both the OECD and the Non-OECD are already guiding downwards, and, will show up decades from now with enormous impact.

We were all entranced with the presentations over the past decade of Wolf-Sheep-Grass systems, and doubling times in yeast cultures. Alas, while humans no doubt will continue to overshoot limits in local domains, more broadly we have already responded. This is why your citations of absolute numbers, such as India’s annual addition of 15 million people, sound impressive to the layman. But, it’s not really about India, per se. BTW, just on this point, I have no doubt a few regions will overshoot hard and may experience very nasty social/conflict outcomes. (Nigeria comes to mind.)

Best,

G

Who knows?

This articles may lead 10 viewers to decide to have less children, which in turn might lead 100 of their friends to change their view on parenting.

100 US babies are the energy equivalent of 2000 African babies 😀

Humans do take signals from resource constraints, but not even remotely close to what is necessary. Humans, including yourself, have completely overlooked the humongous build up of potential premature death. That potential is evident in the fact that we must consume resources faster than they renew in order to keep our numbers alive. We have no clue how to keep 7 billion humans alive at one time without burning oil, and oil is a non-renewable resources. In simple terms we have bred our numbers up so high that we are eating stores of food (oil, coal, etc) and not even remotely coming close to feeding ourselves off the land. This fact makes a mockery of the notion that humans take signals from resource constraints.

A fertility rate trend is utterly useless. Take it to extreme and you’ll see. If 10000 people and their descendants average more than 2 children, while all other 7 billion humans have NO children from now on, all demographers will say that the fertility rate is zero. Yet, humans are still attempting to grow their numbers to infinity at an exponential rate. The ridiculous notion is 7 billion having zero children not the 10000 people averaging more than 2. Yet even that that extreme cannot prevent overpopulation.

The doubling time for yeast example was never presented or understood correctly. It does not tell us that our environment will become full soon, it tells us that it has always been full. It is simply idiotic to think that for as long as humans have been on Earth we have not reached the limit. The example should have shown how yeast were overflowing the beaker, and that represents child mortality. The example should also have shown the beaker being extended higher and higher (improving our ability to extract sustenance from the environment, e.g. farming over hunt/gathering, and fixing nitrogen to make fertilizer), but not quite fast enough to prevent the yeast from overflowing (premature death) in order to properly represent what is going on with humans on Earth.

> “Economic growth incentivizes population growth”

Completely wrong. Poverty is the primary driver of population growth. That’s why we see *negative* population growth in wealthy countries like Germany.

Give this fundamental error, the rest of the article falls to pieces.

But fears about economic recession/decline are prompting Germany to goose up their fertility. This is what I mean by incentivizing. There are actual incentives/programs to grow more babies based on a desire to maintain economic growth.

I have no idea what you are talking about, but it ignores the key point that poverty is the primary cause of population growth.

Furthermore, global population growth is slowing as people are removed from poverty. The real problem is over consumption. To solve that we need sustainable energy systems – and that means renewables.

We were poor for many thousands of years. That didn’t swell the population. Why did the population explosion wait until the introduction of fossil fuels? Maybe lots of babies were born and died in poverty, and the miracle of fossil fuels is that you get to keep and grow those babies (to older ages). However you frame it, I think the surplus energy from fossil fuels played a huge role in building our population.

“Correlation is not causation”. Poverty and high birth rates are somewhat correlated but not all that well, especially as time advances. See the time series:

http://www.gapminder.org/world/#$majorMode=chart$is;shi=t;ly=2003;lb=f;il=t;fs=11;al=100;stl=t;st=f;nsl=t;se=t$wst;tts=C$ts;sp=5.59290322580644;ti=1941$zpv;v=0$inc_x;mmid=XCOORDS;iid=phAwcNAVuyj1jiMAkmq1iMg;by=ind$inc_y;mmid=YCOORDS;iid=phAwcNAVuyj0TAlJeCEzcGQ;by=ind$inc_s;uniValue=8.21;iid=phAwcNAVuyj0XOoBL_n5tAQ;by=ind$inc_c;uniValue=255;gid=CATID0;by=grp$map_x;scale=log;dataMin=282;dataMax=119849$map_y;scale=lin;dataMin=0.836;dataMax=9.2$map_s;sma=49;smi=2.65$cd;bd=0$inds=i239_n,,akak

Modern India has a lower birth rate than much richer countries did some decades ago. Play the graph, and see in recent years many countries having birth rates falling much faster than their income growth.

High consumption, like meat eating, might end up serving as a buffer, e.g. rich countries can cut back on energy use or have more vegetarian diets, rather than cutting back on people living people, which would be brutal.

Poverty causes population growth, when coupled with non-poverty in rich countries.

What caused the explosion of fertility in the developing world? The importation of cheap western food and medicine lowering mortality rates without a corresponding increase in GDP, which would have lowered fertility. Poor countires don’t invent vaccines, contraceptives, new farming methods, etc. Rich countries did that, then exported the technology to poor countries. The solution is for poor countries to become rich.

Another issue is the assumption that higher per capita energy usage = increased pollution. My observation is that environmental degradation is the worst in poor coutnries – the richer the country the more they can afford to do to protect the environment. Protecting the environment is a rich man’s game.

“Economic growth incentivizes population growth”

It’s not clear what “incentivizes” is supposed to mean here. Maybe what you mean to say is that population growth promotes economic growth. That is often, though not always true, simply because more people create more demand for goods. Of course, any sane discussion of economic growth would distinguish between bulk growth and per-capita growth, and any sane economist would acknowledge that the relevant measure for material well-being is per capita growth. But alas, sane economists are hard to find (there are some: http://dalynews.org/learn/blog/)

“But fears about economic recession/decline are prompting Germany to goose up their fertility.”

There is occasionally talk about “demographic decline” in Germany, and discussions about “family-friendly” policies to encourage child-bearing. Many such policies exist btw, without the effect of boosting birth rates. But these discussions are taken far less seriously in Germany than they are by the New York Times and other American observers, where there is a virtual propaganda campaign in favor of population growth, to the point where some have even discovered an “under-population crisis” in China. I’m not making this up. See slides 39-52 at http://www.slideshare.net/amenning/the-human-population-challenge. As I show in detail with the example of Japan, the whole “demographic crisis” argument is unfounded. The share of economically active Japanese (i. e. ages 15-65) is currently higher than it was in 1950. Even if that share declines in the coming decades, there is no reason to expect a labor shortage. Instead, full employment and a slightly longer work life can amply compensate for the change in the population structure. What this issue really shows is the importance of culture. Murphy is looking for correlations between demographics and physical parameters. While such correlations exist, they can and will never provide the whole picture.

Economists fail the most basic accounting principle. Economists do not treat the destruction of fossil fuels the same as an accountant treats a bank account. It makes absolutely no sense to state that the corporation is doing OK while the bank account is plummeting to pay the employees.

We must destroy fossil fuels in order to keep 7 billion alive.

So you have money in the bank that you propose not to spend because then you would have less money in the bank? How about you spend the money in the bank and work toward an alternate source of income (solar or nuclear), which is more or less what we are doing.

Money in the bank is principal or capital. Sustainable use of that money means living on interest. Spending of principal is non-sustainable and leads to bankruptcy. Burning fossil fuels is spending natural capital, as opposed to making plastics which is converting natural capital to a more usable (and re-usable) form, which we can see as investment.

It’s a bit more complex: burning coal to make steel and bricks and glass is also conversion. But burning gas to make fertilizer when we don’t capture runoff, and burning oil so we can zip around faster and have larger homes (which also take more fuel to heat and cool and light) rather than getting around by streetcar, is living on principal.

It’s the difference between spending your inheritance on a college education and spending it on a trip to Cancun. Most fossil fuel use has been spent on Cancun, zipping around in cars and feeding (and powering) an dubiously large population in light of long term energy flows.

I wonder if you’ve seen this paper from Moses and Brown out of SFI. They come to very similar conclusions.

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1046/j.1461-0248.2003.00446.x/abstract

A physicist or engineer gets an idea that seems to explain much of the world. He barges into some other field, and with some graphs or math tells the field experts how his idea sheds unprecedented light on their subject. Sometimes this actually works; I’ve heard of physicists bringing insight to geology or molecular biology. Sometimes it’s just an act of crankitude, in ignorance of the actual key ideas and complexity of the subject.

I’m not calling you a crank, but I think crankitude is within horizon range with this post. “Hey demographers! Energy explains population growth!” But there’s total fertility rate and replacement rate vs. the simple “population growth right now” numbers; there’s the multi-stage model of demographic transitions, where the early boom stages are driven not by energy but by childhood vaccines, antibiotics, and clean water; there’s migration and population change, as I mentioned, and the cultural nexus of eastern European modest-energy states; there’s most of the oil states having distinctive cultural factors other than energy, apart from Norway, which hey doesn’t look like them (though possibly low effort oil wealth has allowed the survival of such cultures.)

The graphs *are* interesting (but maybe based on flawed data, below), per capita energy use clearly is a major part of environmental impact, and we have used fossil energy to boost populations, from South American guano deposits in the 19th century to fossil fuel made (with stranded natural gas more than oil, I think) fertilizers. But “more energy, more people” is I think far too simplistic.

It’s not just Jordan, BTW; the population growth numbers for Luxembourg and Kuwait are also different to a Google search, though off by one point instead of 3. Google credits the World Bank. I don’t know why it and the CIA would differ so much, but -1% for Jordan frankly is far less plausible than 2%. You might try making your graphs with a different data set and see if the curves are robust under such a change.

And what if the foundations of a field are not solid?

Economics is the classic example – complete disregard of the laws of physics reigns there even though the economy is something very much physical. Do you think physicists (and other physical scientists) have nothing to say to economists?

Demographers also have a blind spot and it is evolutionary and behavioral biology because if there are subjects that have something to say on how organisms make reproductive decisions, it is those. Yet, I never see them mentioned by demographers, instead it’s the same mantra of the “demographic transition”, “economic growth leads to lower fertility”, etc.

Well, maybe it does in some cases, but that does not mean it always does or that the relationship is what you think it is. It is not a bad idea to hear what others, who have not been living in your bubble, have to say on the subject.

I hear you. I’m definitely not up to snuff as a demographer. I’m not trying to put them out of business or claiming I have some amazing insight that has slipped their attention. I got data and plotted it, and was surprised by what I saw. Worth sharing. The context is clear enough: I am not isolating fertility, but looking at the end result of many factors influencing population growth. Energy rich countries tend to grow their populations. This has big implications for future energy demand. I care about that.

Also, it was energy-enabled revolutions that stymied Malthus in his predictions of running out of food. So whatever criticisms this post deserves, I am still sold on the notion that surplus energy played a huge role in agriculture and therefore food production, and therefore population. It wasn’t the only way that fossil fuels aided the population boom. But the fact remains that we don’t have a prior experiment to tell us how population responds to the tail end of the finite resource that has given us so much.

“I am still sold on the notion that surplus energy played a huge role in agriculture and therefore food production, and therefore population.”

This is just so obvious I can’t imagine how anyone would take issue with it. We haven’t been able to escape the limits imposed by ecological production of complex carbon molecules (which provide 97% of the energy we use today), so therefore we are still subject to the same rules governing die-offs that hares or deer on an island are, or what have you.

The simple fact remains that without our external energy sources from fossil fuels (or some other replacement, which we do not currently have nor will likely develop in time), there is no way the world would be able to support 7 billion people, end of story.

Of course it gets a bit more complicated in determining how exactly those issues interact, of increasing energy use –> leading to increasing population growth as mortality rates drop –> and then subsequent decreasing population growth rates as fertility rates drop (or sometimes don’t) due to a variety of issues that have been brought up well in the comments here.

The big question in my mind is what will happen to population growth rates when we start going down the back side of fossil fuel curve and people are thrown back into poverty, and social order falls apart, along with education and medicine etc. Will all those previous gains in reducing fertility rates drop?

When we start seriously sliding down the back side of the Hubbert curve, what will happen in the most likely scenario is the following:

1. In advanced industrialized countries, you will see an initial decrease in fertility. This has in fact been observed in real life after the collapse of the Soviet Union and it also likely happened during the collapse of the Roman Empire (though obviously good data is hard to obtain in that case) So it’s reasonable to think that when the analogous processes play out in the West, the consequences will be similar.

2. This, however, will be the case only until society has collapsed to a sufficiently low third-world level. Then two things will happen. First, the majority of people will become subsistence farmers again, child labor will become a normal thing again, and children will be again valuable as a resource and not burden. Second, as whatever small gains have been made in moving us towards a more rational society are lost with the falling apart of educational and scientific infrastructure, religion will regain its complete dominance over people’s thinking. This will be in who knows what twisted insane forms, but more likely than not it will be strongly pronatalist as that’s the the attitude of its most aggressive forms today, which are most likely to survive and become dominant in the future. In the end, it will be back to a present-day Sub-Saharan Africa situation everywhere in terms of fertility. I obviously cannot give you a timeline though.

3. In the present-day Third World, it will be just a continuation of BAU

Note that the above concerns fertility expressed in expected number of children per woman that reaches reproductive age. In the same time this is happening, population will likely be decreasing because mortality will go through the roof due to the inevitable consequences of our ecological overshoot plus the occasional (possibly waged with WMDs) war here and there.

Demography is most definitely a field that needs to be barged into.

One clue is their own pathetic lack of definitions and understanding of existing definitions. The definition for “overpopulation” that is shown on Wikipedia illustrates the inability to comprehend the meaning. The definition states that it is the situation where the organism’s numbers EXCEED the carrying capacity. That can only happen if the organism is consuming resources faster than they renew. Humans are blatantly doing this. The rest of the article shows countless demographers failing to comprehend a simple definition.

They have no definition for the situation where the species is at the limit of what can be provided for (notice I say “provided for” in contrast to “sustained” because provided for allows the use of resources faster than they renew). It is impossible to exceed what can be provided for by definition. What must happen if adults average too many babies? Children must die. The only way the environment can prevent the population from growing faster than the environment can provide for them is by killing children.

Demographers have no definition for this. They never ask the question as to whether humans are in this situation. They assume we are not at the limit. We are at the limit. We have always been at the limit. We have always been causing the death of children when we create a baby. We have always been attempting to drive our numbers higher at a rate that exceeds what we have managed to provide for.

Demographers are utterly clueless to these fundamental concepts.

“The definition for “overpopulation” that is shown on Wikipedia illustrates the inability to comprehend the meaning.”

“Overpopulation” is not a well-defined scientific concept. Better not to use it. It’s counterproductive at best. Remember the damage done do sane debate by Paul Ehrlich’s “Population Bomb”.

Great work Tom,

If you plot fertility rate instead of population growth rates, many of the distorting issues surrounding immigration would be resolved. For instance, Singapore has a fertility rate of 1.4 children per woman, but its government sponsored immigration lifts population growth rate to 2% on your graph. Australia’s population is growing at 1.8% pa, but 60% of that is via immigration where fertility rate is 1.9.

So energy sucks in population from around the world.

If I’m not mistaken that was the whole point: effective population growth is higher, whether it comes from fertility or migration isn’t important.

Except it is important, because fertility is making new people, while immigration is a person moving from somewhere else — energy use goes up here, goes down over there. Migration from a low to high energy country might mean more energy use overall, but not as much as from simply adding a new person. And Earth as a whole has no immigrants, so if wealth leads to low national fertility, global wealth leads to global low fertility.

I can’t help but feel like Prof. Murphy is carefully dodging the elephant in the room on this one: religion. Most of the countries that have high population growth and high per capita income are strongly religious, in particular the the middle east and (in some groups) the US. The countries that are rich and have low or negative growth are, for the most part, the countries with the lowest levels of organized religion.

Good point. Add it to (near the top of?) the list of important factors.

Well watch this argue convincingly that religion is not the large mammal in the room but that education for women is, as Tom says [excellent graphics and cracking german accent too]:

http://www.ted.com/talks/hans_rosling_religions_and_babies.html

Hans Rosling is a fine example of the conventional wisdom of demographers. His presentation is totally based upon projections of the past to the future. That’s all that demographers do.

Imagine if it was 500 years ago and I published a projection into the future of the number of islands discovered by Europeans during the past several years. My projection would suggest that the discoverers could find new islands every year. We know this is ridiculous because we know there are only so many islands on Earth to be discovered. Demographers do this by projecting population sizes into the future, as if it is just a matter of human will power to provide for as many humans as we pack onto the Earth.

Hans totally abuses the projection technique when he projects lower fertility rates into the future. There is no mass or momentum to fertility rates. Demographers have found no mechanisms, only correlations. The mechanisms that they propose to explain the drop in fertility in relation to wealth is utterly ridiculous. We know the mechanism that is certainly present. Too many people causes poverty. Too high a fertility rate causes poverty. To flip this around and say that the poor countries must become rich in order to stop making babies so frequently horrible science. It is nothing more than a systematic abuse of correlations, and projections.

Religion is one the two elephants in the room. The other is the need for a quick and organized by states worldwide population reduction if we to avoid it being forced on us by nature.

Both are too inconvenient to touch, which is why the discussion on the topic is what it is today.

Why is it that economists are so in love with perpetual economic growth? Part of it is simple indoctrination into the religion, but the root cause is that t is an extremely good message to send politically so that’s what they do.

The reason why we have the “demographic transition” theory is the same – it is a politically correct, feel-good message to send, especially in its simplest from – raise GDP and fertility will drop. Of course, there is a slight problem and it is that it is directly contradicted by data once one looks at the oil kingdoms and the US. The economists just ignore that, but the more thoughtful social scientists reframe the argument into “education and empowerment of women will bring down fertility”. Well it does. However:

1) It is not for the reasons they think it does. It is not that people all of a sudden want smaller offspring because they got educated, it is because once you start living in a world in which education matters the investment in resources you have to make into maintaining your social status in it puts a limit on how many kids you can have. Unless you’re a celebrity and/or a billionaire, in which case you can afford nannies, private tutors, etc. and you can have all the kids you want (and, indeed, if you’ve noticed, most such people do not stop at two),

2) More significantly, education and empowerment of women will bring down fertility globally down to sub-replacement level on a time scale of many decades to a century. Well, we neither have that kind of time, not do we have the resources to support the economic growth in the Third World that is supposed to bring that change.

But, again, nobody has any desire to hear that, so we’re back to “improve the economy, educate people, bury our heads in the sand”

If the cost of education is the limiter, then the US, with common private schools and increasingly expensive college, should have a lower birth rate than Europe where education through college is cheap or often free. European countries also subsidize families in many other ways: extended parental leave, cheap day care, free health care, further lowering the cost of having kids.

This is not the case; US has higher birth rates.

“education and empowerment of women will bring down fertility globally down to sub-replacement level on a time scale of many decades to a century”

Rates are dropping as we speak. World fertility rate is 2.55. The replacement rate is actually the inverse of how many children don’t make it to having kids of their own, so 2.1 or less for the First World, but higher for less healthy countries.

“quick and organized by states worldwide population reduction”

Meaning what? Mass forced sterilization? Death camps?

1. You display the same kind of simplistic thinking that leads to declarations such as “fertility will drop as GDP rises”. I never said the cost of education is the only factor, that’s a strawman. I said that the drop in fertility with increased economic development is the result of people having to invest resources they would have otherwise invested into raising offspring into achieving/maintaining social status for themselves and for their kids. There are opposing factors though, one of which is social norms and traditions that prize high fertility. In the US the latter are much stronger than they are, and that’s not true for the whole of the US, but for certain parts of it and certain ethnic groups in it. Massachusetts is a lot closer to Europe than the average for the US towards which the fertility of Mormons, Quiverfulls and other fundamentalists, Latinos, etc. is counted.

2. The more important observations is that tates have not been dropping as fast as predicted. That’s why the UN had to push its projections for the end of the century up. The simple mathematical reality of exponential is that a global fertility of 2.55 is nothing to be happy about, it’s a disaster. Withdraw fossil fuels and watch how we feed 7 billion people – we can’t. Now what about the 10.5 billion projected under the optimistic scenario? Which itself is based on the assumption that the Third World will develop economically, which itself is an absurd assumption because the resources for that are simply not available. Even if the resources were available, that would result in an even bigger global environmental catastrophe – more degrees of warming, more extinctions, more ecosystems collapsing, etc. I have never been able to understand how anyone can think that there is nothing to worry about because we will supposedly reach 10 billion and then growth will level off. Just look at what the effects of 7 billion people are – how is 10 billion going to be anything but much worse (the environmental damage each additional person does not scale linearly with population size).

3. Of the people alive today, at most a few tens of millions will be alive in 2100. There is no need for death camps – all that has to happen is for most people to go childless. If that doesn’t happen, I am willing to bet there will be a lot of death camps in the future, but not ones set up with the explicit intention of population control. Of course, most people will strongly object, which means that forced sterilizations, abortions and infanticide will have to be implemented, combined with a mass educational campaign so that the next generations grow up fully aware of these issues and why population needs to be kept in check. But that’s much better than the alternative.

It’s not going to happen though, so there’s no need for you to worry about it.

“not do we have the resources to support the economic growth in the Third World that is supposed to bring that change.”

Do you have numbers behind that? I am quite dubious about that assertion. Said growth doesn’t have to be as intensively fossil-fuel based as it has been in the currently developed countries. And if we are discussing multi-state efforts to accomplish highly controversial goals with world welfare in mind, a world-wide push for more sustainable forms of economic development (and less resource-intensive economic activity across the board) would seem to be on the table too.

“Do you have numbers behind that?”

I was curious about those numbers too so I did the calculations. I’m pretty proud of how my fairly simple calculation of the proportion of global Net Primary Production appropriated by humanity came to 10% of the total for the world, which is very close to official estimates that peg it at 12%. Whether that’s by fluke or good math, I’m not sure…

The problem is, our agriculture doesn’t “produce” more food; we merely destroy natural ecosystems and replace with our own domesticated ones, totally subsidized with unsustainable fossil fuel and irrigation inputs, and with no replacements on the horizon.

Arguably, the total NPP of the planet has not gone up at all; many say it’s even gone down a bit, even with all the agricultural gains we’ve enjoyed via the Green Revolution over the half last century.

The results of the calculations are pretty sobering, actually downright depressing. It might be theoretically possible for everyone to put solar panels on their roofs and drive EV’s around, and transition to a manufacturing sector using electricity rather than natural gas and coal, but the completely transformative changes that would be required for this are well beyond the time frame (and fossil fuels to manufacture it all) that we have left. It’s not about bringing the third world up to western standards; it’s about preventing the first world from sliding down to third world standards.

http://markbc.net/doomer-economic-commentary/world-energy-use-and-ecological-productivity-an-order-of-magnitude-perspective/

Actually, religion has little to do with it. Both Ireland and Iran have fertility rate ~2…

See this TED talk: http://www.gapminder.org/videos/religions-and-babies/

Without watching the video, I’ll note that the populations may not be as religious as their recent reputations, or as their government. There’s often a strong secular backlash to clerical domination, cf. Quebec.

Your proposal to not have children or at least consider it as an intelligent response seems only rational given your view of the future.

On the other hand, it could also considered a kind of suicide because one is afraid of dead.

When my parents decided to have children around 1979 they were terrible concerned with dying forests (Germany), atomic war (cold war), energy and economic uncertainty (aftermath of the oil shock) etc. and yet despite frequent crisis and much complaining about the increasingly pessimistic outlook I must say that I have had a terrific life (so far). My hope is that the same will be true for my unborn daughter. And if everything collapses there might be hope because I also do not believe that a life can be very enjoyable without most of our modern luxuries.

You ask “by supporting starving populations now, are we only doubling down so that the number of ultimate sufferers is larger?”

Well, Ethiopia had their infamous famine in 1983-5, the one that prompted “Band Aid” and a massive international response. The population of Ethiopia in 1983 was around 33.5 million, of which about 1 million died (if you accept a disputed UN estimate).

The population in 2013? An estimated 86.6 million, to which you can another 6 million in Eritrea (which split from Ethiopia in 1991). So that’s not far short of a tripling in population since the famine and the aid.

This is typical bad reasoning. If the population was able to triple, then we can conclude it can triple again. If the population had famine with 33 million and just normal starvation with 86 million, then clearly we need to add more people!

Clearly this is nonsense logic, but the only difference between this bad logic and the logic that demographers are doing is how sophisticated their correlations and projections are.