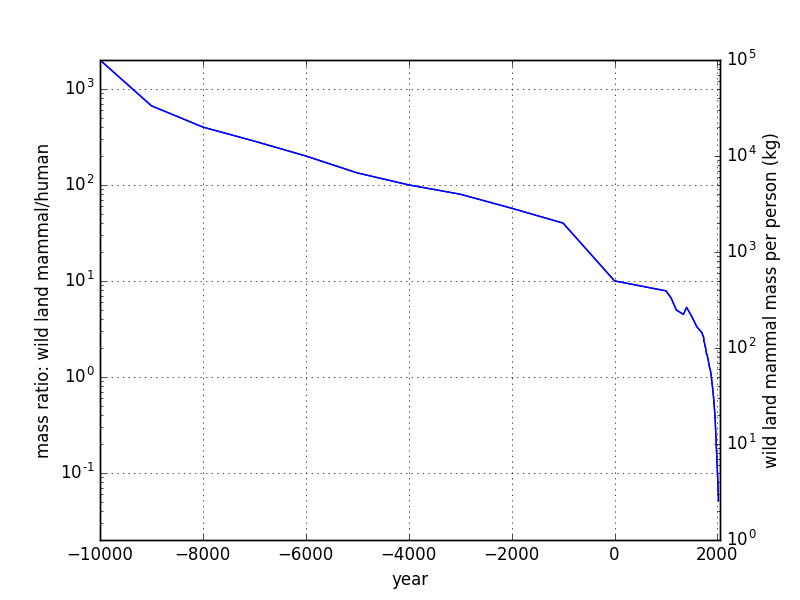

The numbers had already left impressionable marks on me, and as they swirled in my head for some months I certainly had a sense for the urgent warning they wanted me to hear. But it wasn’t until I rubbed the numbers together that the message really rang out. Then plotting the historical evolution shook me anew. I was staring at the ecological cliff we appear to be driving over.

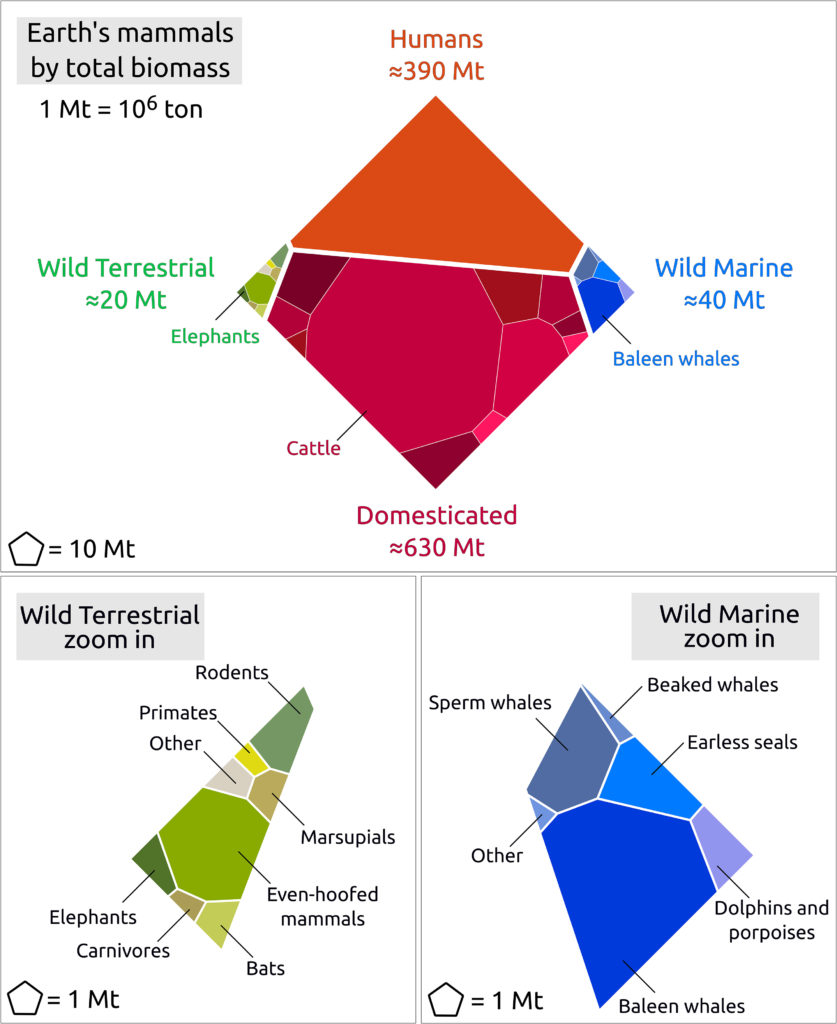

Let’s build the punchline from a few facts that were already rattling around in my head. Human population, at 8 billion today, was 1 billion around the year 1800. At a global average human mass of 50 kg, that’s 400 Mt (megatons) of humans—matching the 390 Mt I had seen in a superb graphic from Greenspoon et al., shown later in this post. This same graphic shows wild land mammal mass at 20 Mt today. I also knew that wild land mammal mass was about 4 times higher in 1800, and 5 times higher 10,000 years ago.

Put these together, and what do you get? In 1800, every human on the planet had a corresponding 80 kg of mammal mass in the wild. Wild land mammals outweighed humans in an 80:50 ratio.

Today, each human on the planet can only point to 2.5 kg of wild mammal mass as their “own.”

Let that sink in. You only have 2.5 kg (less than 6 pounds) of wild mammal out there somewhere. A single pet cat or dog generally weighs more. Not that long ago, it was more than you could carry. Now, it seems like hardly anything! I especially fear the implications for mammals should global food distribution be severely crippled.

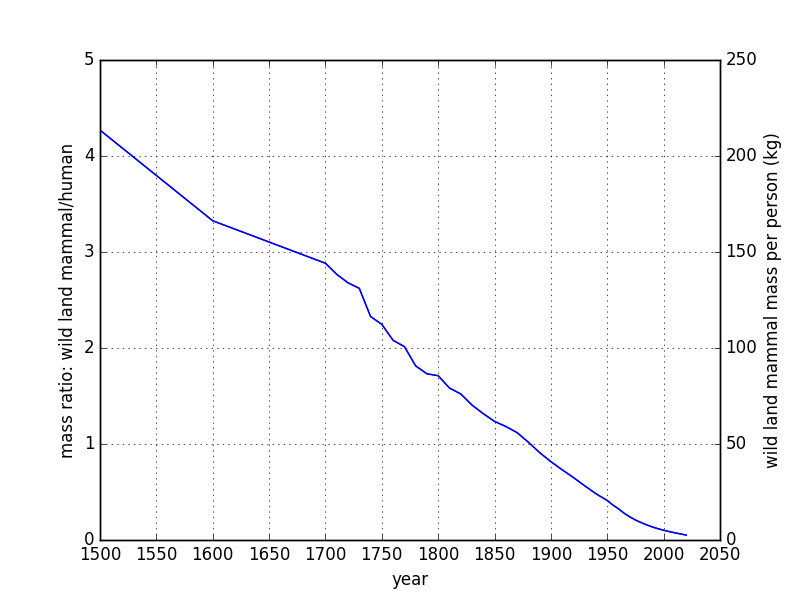

The graph is even more alarming to me.

Mass ratio (left axis) and total mass (right axis) of wild land mammal mass per person on the planet. Note the logarithmic vertical axis, as is necessary to show the wide range of values.

The vertical scale is logarithmic in order to show the enormous range involved. The precipitous drop in the present age is staggering. How can we look at this and think that we’re heading in the right direction? That’s modernity for you, folks.

I front-loaded the core content, and what follows is simply housekeeping. First, here is a linear graph of the tail end of the long-term graph.

We’re almost there! We can do it! Or wait: pull up! Pull up!

Most of the character in the curve—especially until about 1800— is simply a reflection of growing human population while land mammal mass was relatively stable. Since that time, human population has increased eight-fold, while mammal mass has decreased by a bit more than a factor of four. Combined, this is about a factor of 35 (e.g., roughly 80 kg vs 2.5 kg per person).

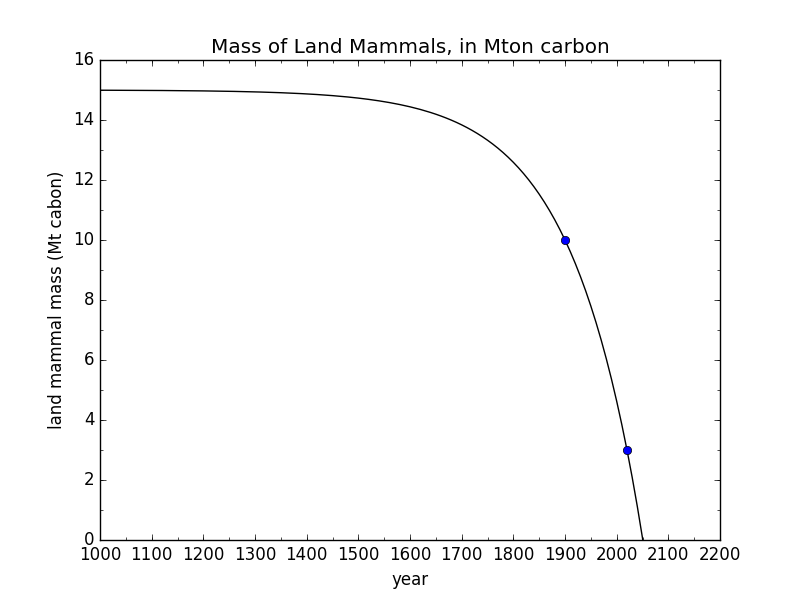

For mammal mass, I used two sources. One came from an aggregation of data incorporating Barnosky (2008), Smil (2011) and Bar-On et al. (2018), as presented here. These data show dry carbon mass of land mammals declining from 15 Mt 10,000 years ago to 10 Mt by 1900, and 3 Mt today. From this, I construct a smooth exponential fit that looks like 15.0 − 10.37×exp[(year – 2000)/137.07]. The graph, below, also appeared in the Death by Hockey Sticks post.

I translate the dry carbon mass into living wet mass based on the Greenspoon et al. (2023) data.

The graphic shows wild land mammals at 20 Mt, implying that 15% of the mass is in the form of dry carbon. This checks out against other information: 70% of mass is water, and half of the dry mass is in carbon form.

Incidentally, straight from this graphic, we see that land mammal mass is only 5% of human mass. At an average human mass of 50 kg, we recover the 2.5 kg of mammal mass per person.

That’s all. It’s a brief “special edition” post without elaboration. The shocking result speaks for itself. What the hell are we doing?

Views: 9758