A post from last year titled The Ride of Our Lives explored the game theory aspect of modernity: those who adopted grain agriculture and new technologies had a competitive advantage over neighbors who didn’t. The “winners” were destined to be those who followed the path that we now call progress.

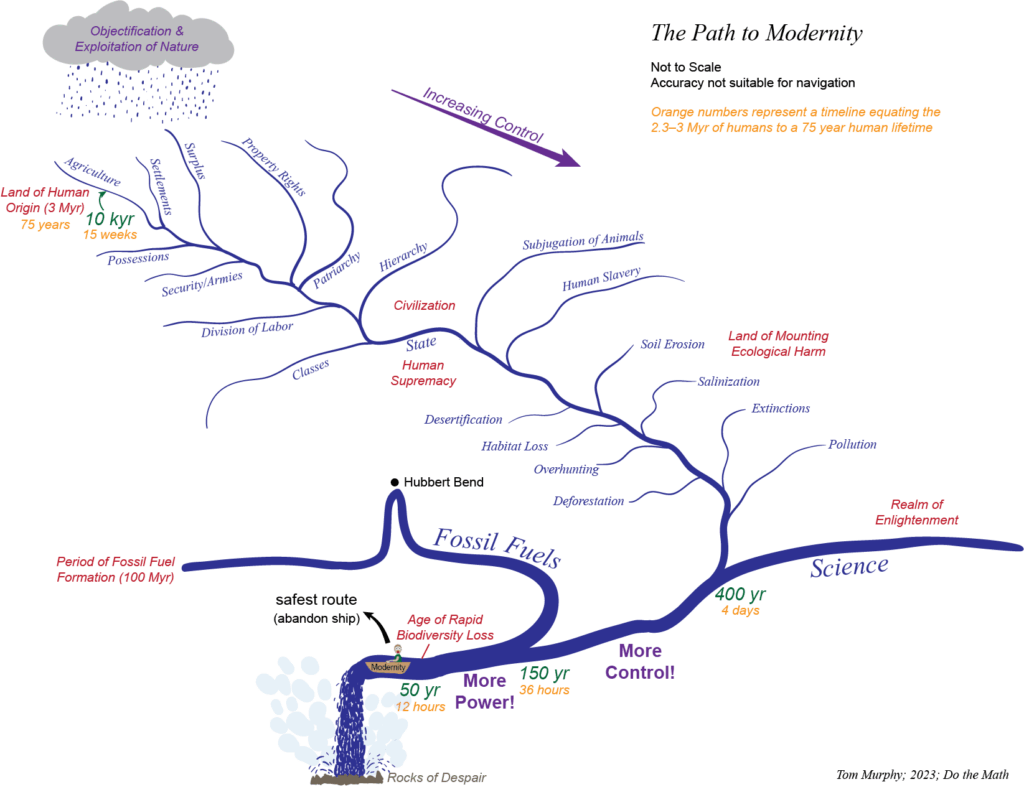

In that post, I used the metaphor of a gentle stream turning into a swift river—by now a raging class-5 rapid—heading toward an inevitable waterfall as a feature simply built into the landscape from the start. In this post, we will examine this river more closely, pausing to pay tribute to the various tributaries that contribute to its estimable flow. I even drew a map!

Metaphorical map of modernity’s journey. The orange time references relate to the post: The Simple Story of Civilization. Click the image to enlarge.

Here is a PDF (vector graphics) version. I suggest having this open in another window while reading the post.

Before Wading In

Humans have been around in some form for 2.5–3 million years. Homo sapiens came onto the scene at least 200,000 years ago. During much of our time on the planet, we dabbled in horticulture: favoring certain plants, tending to “food forests” and landscapes, sometimes using fire to condition the land. Metaphorically, we might say this was dipping a toe, or even wading into the headwaters of modernity.

When Europeans encountered Native American territories, they did not recognize the “tended” landscapes as agriculture, because they still looked untamed. For instance, some tribes planted corn, squash, and beans—the three sisters—intermingled in an unruly but cooperative mess that looked nothing like well-ordered (civilized) row crops.

Agriculture: The Commitment

Roughly 10,000 years ago, some humans began a new form of agriculture that is recognizable today: clear a field, plant a single crop on it, yank weeds, eliminate pests, fence out intruders, fence in beasts of burden. It did not happen overnight, obviously, but adoption of these techniques is what we mean by the agricultural revolution. Daniel Quinn calls this style “totalitarian agriculture.” It was at this point that we committed ourselves to the stream. We allowed our feet to lose contact with the rocky bottom, and enjoyed being pushed along by a gentle current.

This initial branch of what later develops into a river might be called Agriculture, but just as gravity compels water to move downstream, the motivating force for our metaphorical stream is control. The idea is to be less subject to nature’s whims—securing a more predictable diet for the coming year. Agriculture gave people control over what crops to plant, seasonal timing, where to call home, and began an age of individual autonomy—less dependent on a highly-functional tribal unit (though more dependent on an impersonal system). As alluded above, we also sought control over weeds and pests, and began eliminating predators to control our safety.

This new system had a number of obvious advantages, making its adoption very hard to resist. While it tended to involve more work, the result was generally more predictable. Ironically, though, putting all our eggs in one basket made us more susceptible to famine. Increasing dependence on homogeneous crop yields made us more vulnerable to annual variations, whereas diversity made hunter-gatherers more resilient because a bad year for tubers might be offset by a good year for berries. In this sense, famine was a co-invention of the agricultural revolution: the other side of a single coin, and the cost of abandoning biodiversity.

Once set on our course and drifting down the stream of Agriculture, many other tributaries joined to invigorate the flow. What follows is an accounting of these different tributaries, accompanied by brief notes as to their nature and significance. Each tributary incrementally increased the rate of flow, whether perceptible or not. I can’t guarantee I have the ordering right: it’s hard to keep track of so many tributaries! And in practice, these influences often operated in gradual, overlapping progression—rather than as a sudden jolt of fully-formed novelty. So don’t take the map metaphor literally: it’s not meant for navigational purposes.

Settlements

Once tending fields, the nomadic life was essentially over. Fertile soil dictated where people lived, and settlements sprang up in these locations. It made sense to live next to the field where so much time was spent toiling. Living structures became more elaborate and permanent. It was no longer necessary to relocate periodically, so settlement structures became larger and relied more on heavy materials.

Possessions

Relatedly, once settled into a sedentary arrangement, it was possible to accumulate possessions. Before this, few things were “owned” by a tribe, and many of those things might be considered to be communal. Now, living in the same dwelling year after year, personal belongings could be hoarded and treasured.

Surplus

This was a pretty sizable tributary. Control over how much to plant, together with periodically poor yields suggested a “safe” strategy of planting more than was absolutely necessary. In most years, this translated into surplus food. A surplus has all kinds of implications, some of which will appear below. But primarily, it served to encourage higher rates of reproduction—with the added bonus of more hands to work the fields. More people meant the need to transform more land, to maintain the surplus buffer in the face of having more mouths to feed. The expansion game was on!

Security

Food surpluses and possessions needed protection—both from invading competitors and from members of your own community (introducing: crime!). The fruits of so much work would not be taken without a fight. So we developed ways to lock up food and task some with its protection. Full-time soldiers fit the bill, and had the bonus of being able to bring home loot from the invasion of bordering regions!

Property Rights

Once individuals had permanent structures containing personal possessions adjacent to land that they worked, it was an obvious step to associate those holdings with the person. In a move that still baffles those who live as reciprocal members of the community of life, it became customary to assign ownership of land to individuals. Usually, this meant that anything—living or inanimate—within its boundaries was owned by the master of the land. It’s a subtle formality, but the philosophical implications are huge in terms of how humans relate to the natural world.

Patriarchy

As soon as land, home, and possessions were associated with an individual (a man, in practice), the parental (paternal) instinct to pass every possible advantage to direct offspring predictably led to patriarchy. The male lineage became hugely important. This also promoted obsessive attention to rules regulating which offspring were truly entitled (often the eldest born in “legitimate” circumstances). Note that monotheistic religions took root during this same time and context.

Division of Labor

This tributary has already been exerting influence for a while, but at an ever-increasing scale. I deferred its coverage because it is obvious by now how multi-dimensional the society has become. We already saw the need to have security guards or even a standing army. Folks would emerge specializing in construction, farming tools, weapons, lock and key, and law—among other vocations. Even on the farm, we could imagine specializations developing.

Hierarchy and Classes

A natural consequence of division of labor and differing amounts of possessions is a ranking system establishing degree of importance. This is in contrast to our egalitarian past, where age might confer a certain respected status, but otherwise instability-seeding hierarchies were deliberately squelched by a variety of clever norms. Allowed to flourish, hierarchy will run the gamut from divine monarchs to sub-human slaves. Note that hierarchies among humans will not exist without also perceiving a hierarchy within nature, with humans obviously perched at the top. It is a small step from hierarchies to semi-permanent classes as status and privilege are locked in and inherited.

The State

For some time now, we have been cruising through the realm called Civilization, guided by a culture of human supremacy. All of our recorded history is in this context. At every point along the journey to this point, new questions arose. Who is the boss of the security forces? Who sees to their payment? Who controls surpluses? Who adjudicates property rights? I had difficulty deciding where to bring in this tributary, since it evolved at every stage and scale from villages to kingdoms. So we rename the river at this point: the river State. Who knows how long we’ve been on it, exactly? I could just as easily have called the realm State and the river Civilization, or even Human Supremacy. Don’t make the mistake of expecting the metaphor to be, you know, accurate. Just go with the flow.

Subjugation of Life

Agricultural life is labor-intensive. It also means that individuals have little of the self-sufficient autonomy that most members of a hunter-gatherer tribe possess—where almost everyone shared an impressive suite of skills and could acquire food by their own lights. Once food was the result of a segmented, labor-intensive process placed under lock and key, humans were beholden to power structures, which often were not terribly compassionate. Slavery provided necessary labor and was another one of those tributaries that accelerated the flow. It is hard to see how it would not have emerged from the conditions unleashed by committing to the agricultural stream.

Besides enslaving humans, we have a long and continuing history of enslaving animals to perform services for us (with their food under lock and key). Some may defend the practice as offering shelter, food, parasite control, protection from predators, and other amenities. We’re doing them a favor, it is claimed. My question is: if you remove the fences (prison bars; chains), do they still decide to stay? Granted, at this point the genetics of many domesticated species are so compromised as to render them non-viable in the wild—stripped of much of their initial (and considerable) bio-intelligence. But what would we think if human slavery had persisted long enough to produce similar genetic alterations and incapacities? Would that then make it okay to retain institutionally-dulled humans as slaves? Humans are animals, too, and applying different rules and considerations is a hallmark of human supremacy.

Objectification and Exploitation

This is not so much a tributary as a characterization of the rain that sourced all these tributaries. But it makes the most sense to talk about it now. As soon as we take control of who lives and dies (crops, weeds, pests, animals), decide that we can “own” land, accumulate a lot of “things,” commodify food, and transform living beings into property, we have stepped deep into dangerous territory. It is no surprise that such a culture would develop an ingrained sense of human supremacy.

Even our language reflects this transformation. Compared to many Indigenous languages, the languages of modernity are very noun-heavy. Lots of things. Trees, rivers, and fish are all objectified things to us that are simply resources available for exploitation, whereas Indigenous languages are verb-heavy. It is to be a tree, to be a river, to be a fish (or something to that effect—I’m no expert). In this sense, such languages are animist: imbuing the entities around us with a life force, dynamics, and a bio-intelligence hard-won through the sheer and non-trivial feat of long survival.

General-purpose money—exchangeable for practically anything of value—is an outward manifestation of this objectification, and arrived as a seemingly inevitable partner to our objectifying, agricultural ways. This construct facilitated and accelerated the pace of unfortunate, exploitative decisions.

Ecological Ills

Having established the core character of the now swiftly-flowing river, it begins to exercise erosive power over the landscape. Early on, it became apparent that totalitarian agriculture was a form of soil mining. Nutrients were depleted. Salt accumulated from irrigation. Tilled soil lost its root structures and blew or washed away. What was once a forest, then a crop field, became a spent desert—a bad bargain for the community of life. Habitats were ruined and lost forever. Species were unwittingly driven to extinction as collateral damage. This segment of the map is riddled with tributaries representing one or another ecological tragedy. Civilization built itself up at the expense of ecological health. We lack evidence that one is possible without the other.

Science

This isn’t just another tributary, but the confluence of a fully-formed (even larger) river. Up to this point, a key subtext has been control: over plants, animals/humans, and the environment in general. Science (or perhaps more generally the Enlightenment) provided systematic tools for more effective control. Experiments methodically improved our understanding and ability to predict and manipulate the world in which we lived. At almost every turn, this knowledge was used to increase profit, increase the human footprint, and drive technological development—all to provide goods and services to a single exploding species in the short term. The primary application of this knowledge has not been to benefit the entire community of life, and generally has had quite the opposite effect.

The introduction of science marked the beginning of a rapid acceleration of the modern enterprise. It deepened the sense of separateness and transcendence from nature. It planted the false notion that we could overcome any limit—ultimately perhaps even death itself. It was the elixir of godly ambitions. I can hardly overstate how much of a game changer it was to merge our already-destructive stream with science. Incidentally, the science label here also covers technology, as an application of the scientific approach.

Fossil Fuels

As if the Enlightenment was not enough, in quick succession we joined another enormous river. One could say that the process of science opened the door to fossil fuels, but science and fossil fuels might be best described as a dynamic duo. Fossil fuels gave us the power to advance our science-amplified degree of control to an entirely new level. Resources that had been previously inaccessible became available. It became far easier to clear land for agriculture and other uses. We learned to make fertilizer from methane, unleashing unprecedented agricultural surpluses that inevitably resulted in a human population overshoot. Fossil-fueled furnaces led to steel, concrete, and other materials on a massive scale, paving the way to megacities and global trade. Science itself was amplified by having access to fossil fuels, via a flood of new devices and capabilities invented with—and powered by—cheap energy. Advances in science and technology in turn allowed greater access to buried fossil energy. This positive feedback arrangement facilitated runaway expansion of the enterprise, leading to a battery of hockey stick curves.

Now we find ourselves racing along in a raging torrent! It is both thrilling to think of the seemingly infinite possibilities, and scary to realize how precarious our position has become. On the dramatic end, we have developed the power to annihilate most life on Earth in a matter of minutes. But just in case nuclear war did not come to pass, we set about annihilating life on a more modest schedule of a century or so.

Ecocide and the Boat

I no longer seem to be able to write a post without calling attention to the tragic and rapid decline in wild animal populations (see Death by Hockey Sticks). Our raging river is rapidly eroding the foundations of biodiversity—drowning out most life and extinguishing the vitality of the planet. We have succeeded in whittling down wild land mammals to 2.5 kg per person—small enough to drown in the bathtub (or sink, really).

How are we, ourselves, surviving the turbulence and not drowning? Well, first let’s point out that billions of people are struggling to keep their heads above water in the current system. Not everyone enjoys the fruits of all this extraction, exploitation, and expansion into various habitats. In the river metaphor, I think of a boat built out of technology that keeps the luckier ones dry and safe. It started simply centuries ago, as a few crude logs bound together into a raft. Constant improvements resulted in today’s marvel, complete with LED-illuminated bluetooth cupholders. The boat has a name: Modernity.

We also make room on the boat for some selected plants and animals. It’s like Noah’s Ark, except that we dispatch most animals (and some people) who try to climb aboard. It’s not a very bio-inclusive boat.

Waterfall!

Where do we go from here? One feature of the river metaphor is a sense of inevitability, as was emphasized in The Ride of Our Lives. Logical consequences (all those associated tributaries) teamed up with game theory to ensure dominance of the agricultural, technological, industrial, scientific, market-driven, fossil-fueled juggernaut. This system had the adolescent power to overwhelm older, wiser, gentler ways, and required little thought or deliberate design: just go with the flow, and stay in the center of the channel to maximize speed.

Now we are beginning to see the next inevitable development. A system dependent on growth, stacked to favor one species in the very short term, utterly reliant on non-renewable materials and temporarily copious energy, obliterating ecological health, objectifying nature and leaving important decisions to mindless money writes its own demise in the most elegant, efficient, optimized fashion. This churning, awesome mega-river leads itself over a waterfall. That’s just what it does. It was always so, but not at all obvious from upstream. Even now, so close to the edge, our vantage point on the river is the least advantageous for seeing the waterfall clearly, so that most people are still unaware or unconvinced. But increasing numbers of people see the clouds of mist and hear a mounting sound of continuous thunder. Others at least sense that something is not quite right.

A Bigger Boat?

Probably the most common reaction among the subset of the billions of privileged humans in the boat who even acknowledge the danger is to focus on the boat, and how it might be modified to continue insulating us from limits and danger. Technology, innovation, ingenuity, science, and extraction/exploitation have done marvels in getting us to this state (overlooking the dominant role of the river itself, as we are prone to do), so let’s double down and do more of that! Such reactions tend to be piecemeal: dividing the predicament into identifiable problems that individually might have viable “solutions” but do little to change the overall state of affairs. Solar panels might address CO2, for instance, but not the “meta” peril of ecological overshoot enabled by a hubristic, supremacist relationship to the natural world.

Typical reactions also rely too much on past trends. What worked on the river surface—even in the rapids to some extent—will not apply to a plunge over the towering waterfall. Yet, for solid evolutionary reasons, humans are predominantly backward-looking, devising strategies based on what has come before. It works 999 times out of 1,000, or more. This is not one of those times, putting our species at a marked disadvantage.

Unfortunately, the boat (modernity) seems like the only thing that keeps us safe at the moment. It isolates us from the turbulence and, well, wetness. It’s all we’ve known for generations. The context is changing, though. The boat is becoming a liability. It’s so massive and has so much inertia that it is committed to going over the waterfall—becoming a death trap for those who stay with it. It may have been possible in the distant past to alter course from the middle of the river, putting us closer to the safety of shore. But any suggestions to do so were ignored or ridiculed: the result would be slower progress, inefficiency, and not what the market (current) said was best. It turns out that modernity was optimizing its own speediest destruction—as its definition effectively required.

We might now wish to slow things down, but modernity was built on a lie; a fatal flaw. If we voiced the command: “Slow down, Hal,” we’d get the response: “I’m sorry, Dave. I’m afraid I can’t do that.”

In the next, much shorter post, I will build on this metaphorical landscape to explore reactions that might make more sense. To get you thinking, key questions are whether the boat and the passengers are the same thing, and if we even have to be on the water at all. The predicament is enormous, and requires stepping pretty far back to see a way around it. I hope this high-altitude survey of the river system we’ve traversed helps in developing a clearer perspective of where we are, how we got here, how much agency we have had and can have, and what sorts of options might make the most sense going forward.

[2025.07.08 addition: I missed two major influences/tributaries: written language, and general-purpose money. Both have hugely amplified our destructive power and objectification of the living world.]

Views: 7106