What if we ask a rough-skinned newt, assigning it greater importance than is customary?

To prevent the reader from wondering if they have the wrong blog, I will warn that this post starts in an unfamiliar voice. In some respects, it reflects a younger me. But mostly it channels views familiar to modernity, by no coincidence. We start with a guy (of course) hogging the microphone.

Space is cool. Astronauts are badass. Maybe me too, someday.

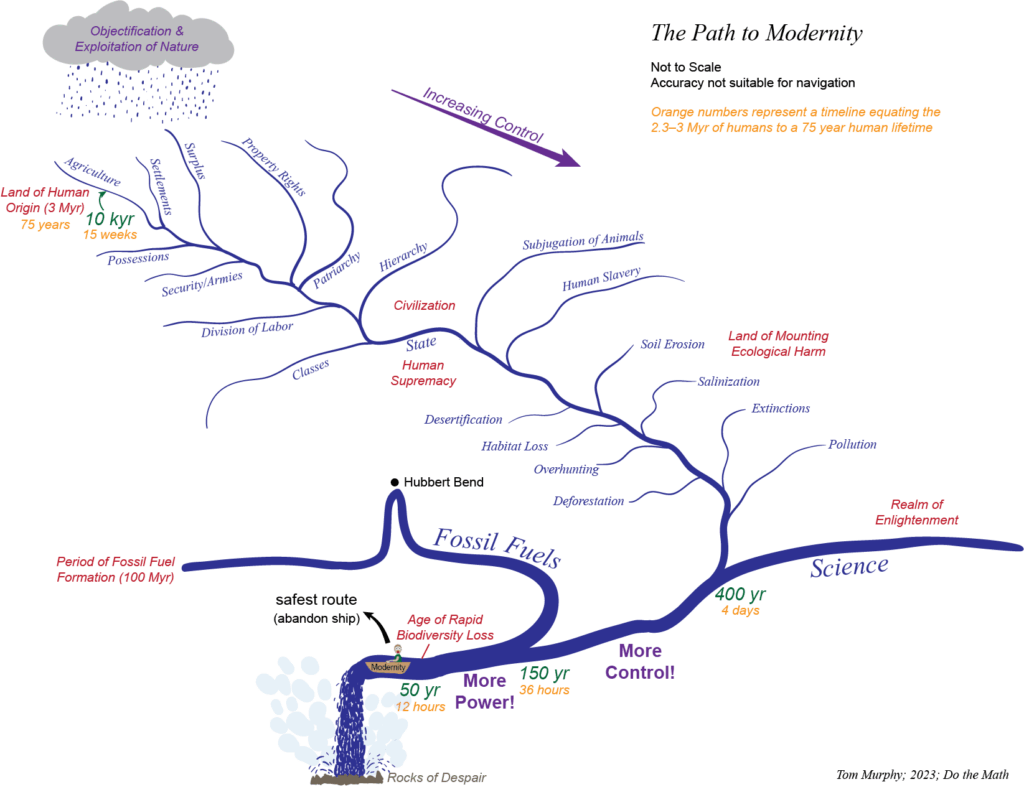

What we’ve learned is amazing—we have tamed so much—our reach and control are ever-increasing.

Information and analysis are accelerating: we’re on our way to mastering everything.

We have learned to outmaneuver all limits. Nothing can stop us from having it all—even immortality may be in the cards soon.

We are so lucky to have pulled ourselves out of the muck—no longer mere animals.

We are so lucky to be as clever as we are: ingenious innovators.

We are so lucky (and brilliant) to have found the fossil fuels that powered our ascent—but that’s just the start.

What’s this you say? Growth can’t go forever on a finite planet?

Well, not to worry: did I mention that space is cool, and that it is in our nature to skirt past limits?

What’s that? Space colonization is a juvenile fantasy, you say?

No, I can’t prove that it’s destined to happen. But why would the burden of proof be on me, when it’s so obvious that’s where we’re heading? What relevance is it that we have no examples even remotely close to sustainable living in space over long durations?

What’s this? Fossil fuels are finite and likely to decline this century?

No matter. Renewable energy: solar, wind, nuclear!

Don’t be a pest. It’s beside the point that nuclear is not renewable—you know what I mean: unlimited energy awaits. Fusion, then.

Wait: too many things at once:

- Of course unlimited energy is a great thing—why the hell wouldn’t it be?

- Why should it be relevant that we’ve never built solar panels or wind turbines without fossil fuels?

- What does it even matter if these technologies use ten times the mined resources as fossil fuels? Earth is enormous.

- Surely, you jest that we don’t have ways to make concrete and steel, carry on our mining practices, support air travel and global shipping without fossil fuels. I can probably find a cute demonstration blasting each of these, or at least imagine them—which is theoretically enough.

- I don’t understand the relevance of your point that most of our 8 billion people are fed by the fruits of fossil fuels for fertilizer and mechanization: we’ll just do something different/better!

So don’t get hung up on fossil fuels! Yes, they are causing climate change, but that’s just another hiccup that we’ll master and tame in the usual heroic fashion: just look at the explosion of solar and wind and electric cars (now roaring up to a few percent penetration!). We’re lucky, remember! Fossil fuels are just a stepping stone to an even richer future. Failure is not an option, say I: we’re increasingly capable and increasingly in control. Our destiny is clear: just look at how far we’ve come! This trajectory must continue. To think otherwise ludicrously ignores a centuries-long trend—even if you do claim to rest your argument on biophysical reality and not on an inheritance-spending extrapolation lasting only a handful of human lifetimes. It’s only your toxic (lack of?) imagination and lack of faith that threatens our greatness: we have to believe in order to mold reality to our dreams.

Hey—how dare you! Give. Me. (grunt) Back. That. MICRoph…

Continue reading →

Views: 3942