We’ve all heard the outrageously skewed statistics. The top 1%, or 0.1%, or even 0.01% of humans control an outsized fraction of total wealth (something like 30%, 15%, and over 5%, respectively). Because our culture values the fictional construct of money far more than is warranted, and the ultra-rich have a hell of a lot of it, they acquire status and access to power unavailable to almost everyone else. How can such a small fraction of the population possess such a disproportionate share of this resource—one that we’ve decided bestows influence and power? It doesn’t seem at all fair.

But, money isn’t the only disproportionate power-conferring asset on this planet. What else does our culture value above almost all else? Brains. What—are we zombies?! Large brains are what (we tell ourselves) set us apart from mere animals—taken to justify a sense superiority. Earth belongs to us. We can do whatever we want, because we’re the ones with the big brains: the self-declared winner of evolution—as if it’s even possible to have a winner in an interdependent community. Through innovation and technology development, we now wield god-like power over the rest of life on Earth—for a short time, anyway, until it becomes obvious that “winning” translates to “everybody loses.”

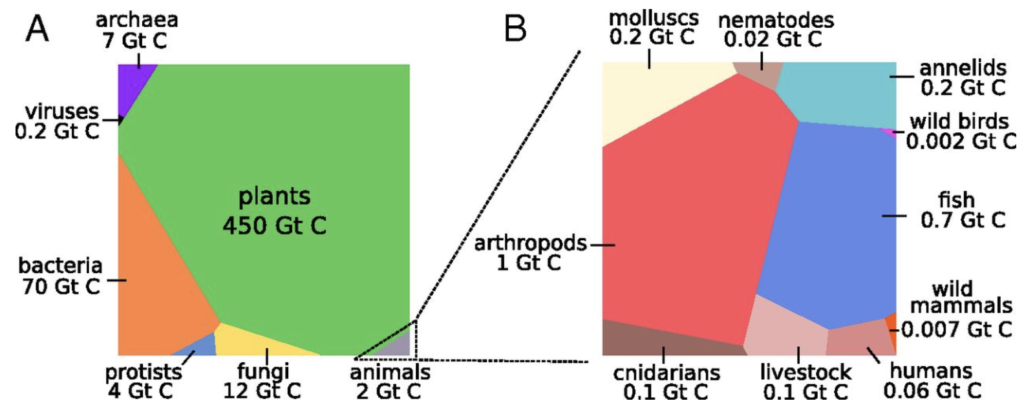

Given our similar tendencies to overvalue money and brains, I was motivated to compare inequality in brain mass within the community of life to the gross inequality we abhor in financial terms. Is it as bad? Worse? Humans constitute 2.5% of animal biomass, and 0.01% of all biomass on the planet. We are also one of perhaps 10 million species, which in those terms means we represent only 0.00001% of biodiversity. Any way you slice it, we are a small sliver of Life on Earth—while managing to dominate virtually every ecological domain. As our culture tells it, humans are the deserving elites.

What fraction of the planet’s brain wealth do we possess? To be clear, in performing this analysis, I am not making the case that brains are what matters—far from it. But in our culture, our brains are cherished and essentially worshiped for their unique capacity in terms of ingenuity, allowing us to defy the limits that all other species “suffer.” What is our disproportionate share of brain mass? Is it as bad as 15% or 30%, like our egregiously-lopsided wealth inequality?

For this exercise, I rely on biomass assessments by Greenspoon at al. 2023 (mammals) and Bar-On et al. 2018 (all life), as well as scattered data I could pick up on brain masses, body weights, etc. I was moderately careful, but not excessively so, as the purpose is not precision but illustration in an approximate sense. I got a result that at least helps me put things in context—better than I could do on a guess.

Humans

We start, as we are wont to do, with our supreme selves. Greenspoon et al. have human “wet” biomass at 394 Mton (mega-tons; metric). Call it 400 Mton (it’s still growing, after all). That’s 8 billion people at an average of 50 kg apiece. The entire mammal population on Earth, including humans of course, sums to 1080 Mton according to Greenspoon et al., so that humans amount to about 36% of mammal biomass.

Human brains are typically about 1.4 kg, so that we’re dealing with about 11 Mton of brain mass. I’ll switch to kilotons for easier comparisons, so that’s 11,000 kton. At this point, feel free to skip to the Summary Table if you don’t care for the nitty-gritty that follows.

Domesticated Mammals

Greenspoon et al. provide a table of domesticated mammals (in the supplement). I folded in some crude estimates of individual mass to get population counts, and added brain mass, resulting in the following table. In this table and the ones that follow, the total (wet) biomass of each species or group is given (in megatons), the number of individuals (population) in millions, approximate brain mass of an individual, in grams, and the total brain mass of that species, in kilotons.

| Category | Mton | Pop. (M) | brain (g) | total brain (kton) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cattle | 416 | 830 | 450 | 375 |

| Buffalo | 68 | 140 | 450 | 61 |

| Sheep | 39 | 560 | 140 | 78 |

| Swine | 38 | 380 | 180 | 68 |

| Goats | 32 | 800 | 130 | 104 |

| Dogs | 22 | 1,500 | 72 | 106 |

| Horses | 16 | 40 | 700 | 28 |

| Camels | 8 | 16 | 600 | 10 |

| Asses | 7 | 18 | 370 | 6 |

| Cats | 2 | 330 | 30 | 10 |

| Camelids | 1 | 2 | 600 | 1 |

| Mules | 1 | 2.5 | 190 | 0.5 |

| Rabbits | ~1 | 170 | 10 | 1.7 |

| Rats | ~1 | 2,300 | 2 | 4.5 |

| Mice | ~1 | 36,000 | 0.4 | 14 |

| Total | 650 | 870 |

Please do not mistake these for definitive numbers. They’re good enough for this very approximate exercise, but not to be taken as authoritative.

The total mass of domesticated mammals outweighs even humans—representing nearly 60% of mammal mass on the planet—while total brain mass in this grouping is about 13 times smaller than human brain mass. How’s that for a stoking a smug sense of superiority? It just gets more extreme as we continue.

Land Mammals

Adding up to a mere 20 Mton (wet), the wild land mammals are highly varied, so that only about 45% are represented in the top ten list provided in Greenspoon et al. Here’s their table, amended with brain data.

| Category | Mton | Population (M) | brain (g) | total brain (kton) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White-tailed deer | 2.7 | 45 | 200 | 9 |

| Wild boar | 1.9 | 30 | 180 | 5.4 |

| African elephant | 1.3 | 0.5 | 4,800 | 2.4 |

| Eastern gray kangaroo | 0.6 | 20 | 35 | 0.7 |

| Mule deer | 0.5 | 7 | 200 | 1.4 |

| Moose | 0.5 | 1.5 | 120 | 0.2 |

| Red deer | 0.5 | 2 | 200 | 0.4 |

| European roe deer | 0.4 | 20 | 200 | 4 |

| Red kangaroo | 0.4 | 1 | 56 | 0.6 |

| Common warthog | 0.3 | 5 | 120 | 0.6 |

| Total | 9.1 | 25 |

First, note the drop in scale compared to previous numbers: this is itself of huge concern, leading to the fact that only 2.5 kg of wild land mammal mass remains per human on the planet: almost gone! But once getting over that shock, we calculate 25 kton of brain mass while capturing 45% of total wild land mammal biomass. So, I apply a simple scaling correction to arrive at a total brain mass of 55 kton for wild land mammals. This likely results in an underestimate, as smaller mammals tend to have a higher fractional brain mass, but we’re probably not off by more than a factor of two, which in any case hardly makes a dent in the running total. Remember: these numbers need not be at all precise to make an overall point.

Marine Mammals

At roughly twice the biomass of wild land mammals—40 Mt—we might expect roughly twice the total brain mass for marine mammals (especially given how smart dolphins and whales are). But whales are huge, and the scaling works out so that fractional brain mass is smaller. In any event, the following table tracks what happens. Note that I have thrown in an extra line for dolphins as a group.

| Category | Mton | Population (M) | brain (g) | total brain (kt) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fin whale | 8 | 0.1 | 6,900 | 0.7 |

| Sperm whale | 7 | 0.4 | 7,800 | 3.1 |

| Humpback whale | 4 | 0.1 | 4,700 | 0.5 |

| Antarctic minke | 3 | 0.5 | 2,700 | 1.4 |

| Blue whale | 3 | 0.05 | 7,000 | 0.4 |

| Crabeater seal | 2 | 10 | 500 | 5 |

| Bryde’s whale | 1.3 | 0.1 | 5,000 | 0.5 |

| Common minke | 1.3 | 0.2 | 2,700 | 0.5 |

| Harp seal | 1.2 | 10 | 400 | 0.4 |

| Bowhead whale | 1.1 | 0.05 | 2,700 | 0.14 |

| Dolphins | 3 | 20 | 1,650 | 33 |

| Total | 35 | 49 |

Accounting for 87% of the total marine mammal biomass in these eleven entries, we need only a small correction to the total brain mass to arrive at 56 kton of marine mammal brain mass—basically identical to the estimate for wild land mammal brain mass, despite twice the total biomass. The economy of whale scale is a hefty part of that story.

Birds

Wild birds amount to less than 0.1% of animal biomass—about 30 times smaller than human biomass, and roughly half that of wild land mammals. I had a harder time tracking down specifics (and was running out of steam to be honest), so I take a bit of a punt, here. The most impressive bird thinkers, like ravens and parrots can have 2% of their body mass in brain form. Guessing an average of 1% across the birds (which comes out high compared to mammals, but okay for smaller creatures) and applying to approximately 13 Mton of bird biomass results in 130 kton of bird-brains. That’s about double wild land mammals for half the mass. Given the uncertainty, I’ll round to 100 kton, but feel free to rework the conclusions with your own number if you don’t like mine (hint: nothing substantive changes).

Domestic birds—dominated by chickens—have a biomass exceeding wild birds by a factor of 2.5, amounting to one-twelfth of human biomass. That’s 33 Mton (wet), translating to about 10 billion chickens. Raisin-sized chicken brains are 2.6 grams, resulting in about 30 kton of chicken brain.

Reptiles and Amphibians

Bar-On et al. characterize the biomass of both these categories as “negligible” among animals. That, together with small-ish brains, leads me to ignore the contribution here, which would no doubt hardly register against the foregoing numbers.

Fish

Fish, however, constitute almost 30% of animal biomass, and they do have brains, however quaint. A shark’s brain is only about one-three-thousandth its body mass, which is 100 times smaller than humans relative to body mass. But the vast oceans contain many fish, and the brain’s fraction of body mass tends to increase as fish get small and numerous.

I also punted on this one, but found two sources of value (here and here), from which I gathered that the biomass distribution of fish is roughly equi-partitioned: similar total mass in each logarithmic mass bin. That means ten times as many individuals between 0.1 and 1 kilogram as between 1 and 10 kg, but amounting to the same total mass. The other piece quantifies the rate of increase of fractional brain mass as fish get smaller. What I find is that the fish in the 10–100 kg range contribute about 150 kton of brain mass; the next decade down 400 kton; then 1,000 kton, followed by 2,000 kton for fish between 10 grams and 100 grams. The next tranche of tiny tots (1 to 10 grams) has about 7,000 kton. It adds up: lots of fish in the sea thinking about seafood, or how to avoid being seafood. The net result is comparable to human brain mass, at about 11,000 kton—very approximately.

Non-Vertebrates?

I stopped at the vertebrates. A cursory look at insects (arthropods being substantial, at 40% of animal biomass) tells me that their aggregate brain mass may add up to numbers comparable to humans and fish. Ants alone, for instance, amount to 20% of human biomass and have fractional brain masses around a few percent, contributing something like 2,000 kton to brain mass totals.

But I don’t really know what I’m doing here. For instance, should I count worms? Do brain stems count? In our wealth analog, worm and insect brains are almost like an unrecognized currency, unavailable for exchange. People in comas are not valued in our society for their innovative capabilities, or even tested in experiments like ravens or mice might be. Since I’m trying to track attributes that humans of modernity value, my strong sense is that it’s more about the cerebral cortex than the portions that maintain bodily functions. Maybe I should be subtracting out brain stem mass, and perhaps even cerebellum. This is well outside the scope of a weekly blog post. While insects (ants, bees, beetles, etc.) obviously have more going on than just bodily functions, it might be most appropriate to just consider mammals and birds in our comparison (sorry, fish). There’s no correct way to do this, so let’s focus more on what we can learn than on the elusive goal of getting it “right.”

Summary Table

It’s worth collecting the foregoing (approximate) numbers in one place so that we might put the matter into perspective.

| Category | Brain mass (kton) |

|---|---|

| Human | 11,000 |

| Domestic Mammals | 870 |

| Wild Birds | 100 |

| Wild Land Mammals | 55 |

| Marine Mammals | 55 |

| Domestic Birds | 30 |

| Reptiles & Amphibians | — |

| Fish | 11,000 |

Comparisons

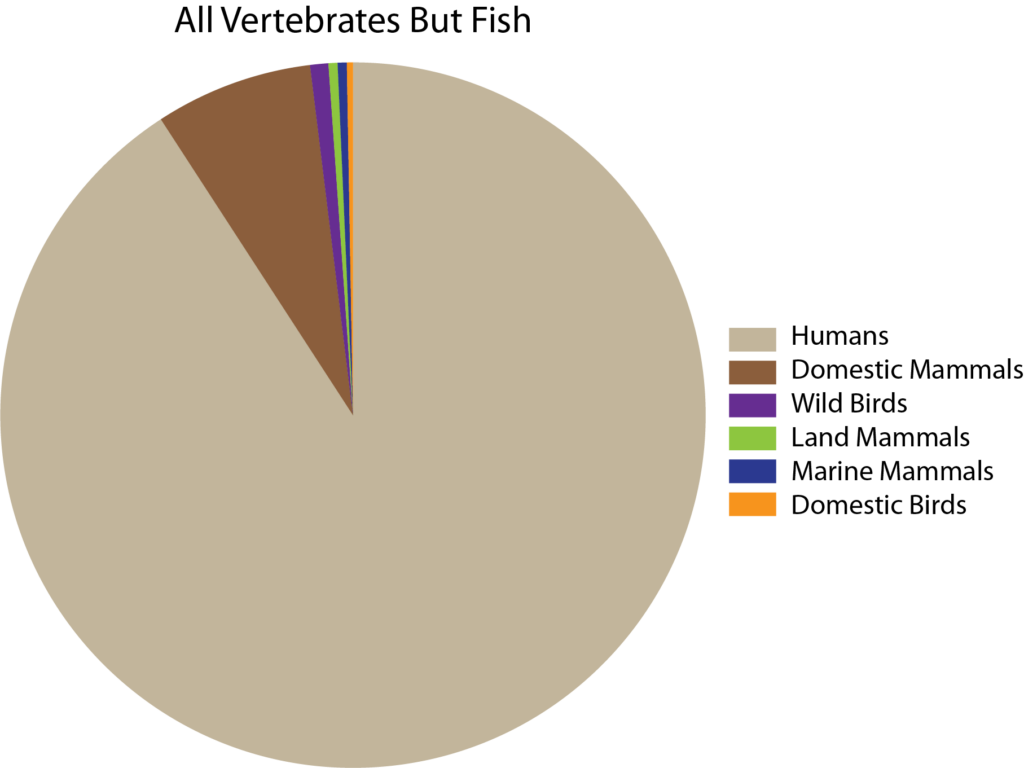

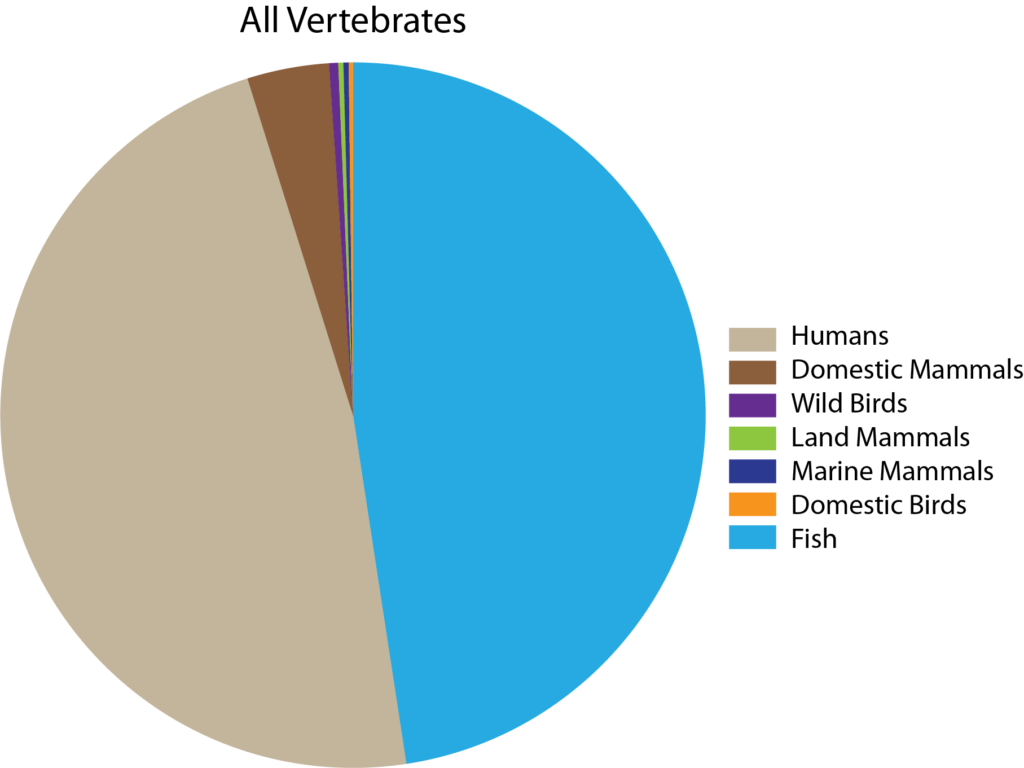

Depending on how one considers fish—which carries a similar ambiguity for some vegetarians—the assessment looks different. The first notable outcome is that a single species (humans) tops whole categories, and even when including fish account for roughly half of vertebrate brain mass on Earth. But let’s first look at the fish-free comparison.

Among mammals, humans hold 92% of brain mass. That means one species out of 5,000 (thus the “top” 0.02%) hogs 92%. Adding birds hardly changes the number (91%). By comparison, in financial terms the wealthiest 0.1% hold “only” 15% of the loot. Looking at the other 99.9% of mammal species, wild land mammals and marine mammals each cling to only about 0.5% of mammal brain mass, making them the poorest of the poor—but wait: we haven’t even gotten to the enormous bulk of life having no brains at all. Are we to consider them more poorly than the poor? Worthless?

Among all animals, 2.5% of the biomass (humans) claims nearly 50% of brains (now including fish). Among all life, humans represent a 0.01% slice by mass or 0.00001% by species, while holding almost half the brain mass. And you thought wealth inequality was bad. Compare these results to the top 0.01% of wealthy individuals hoarding 5–7% of wealth. Brain inequality blows financial inequality out of the water!

What of it?

I am aware that a number of readers might think: well, good on us: more proof of human supremacy. Careful there. Assertions of physiological superiority have a dark history (and present). In financial terms, just imagine the billionaire being pleased with the lopsided nature of his wealth—serving to prove how remarkable he is. (I’m casting the billionaire as a man because these jerks usually are…) Imagine the justifications that are possible for the billionaire who sees his wealth accumulation as validation of intrinsic greatness. How is it any more acceptable when it comes to brain discrimination?

Read the following statements in two parallel ways: a billionaire discussing a poor person, and a human discussing a lifeform lacking brains—like a particular species of paramecium, lichen, spurge, or jellyfish:

They are nothing to me. I might find ways for them to be useful to me, but I doubt it. They are dispensable. They could disappear from this earth and newspapers won’t report it. They neither have nor deserve the power I possess. Only I and my ilk can make the world a better place, accessing tremendous assets. Because the lower classes don’t have the capacity (or luck) to be graced with my resources, that’s just tough for them. How would such a being even be capable of appreciating its plight when they never have and never could experience life as I know it? I deserve to be on top of the heap, and I’ve got the money/brain to prove it.

Give it some consideration: are you a brainist (parallel construction to racist)? Do you believe our brains give us special privileges and justify any action we find convenient to ourselves—no matter the cost to life without brains, or to those with inferior cerebral hardware? Are other species nothing to us except utility—and even then only in some cases? Might such an attitude contribute to the initiation of a sixth mass extinction that we now witness? Might a sixth mass extinction also seal the fate of a large, hungry, complex, high-maintenance mammal? Will it somehow favor metabolically-costly large brains, or will we find it to be unsympathetic to our own admiration?

Beyond Brains

There’s a lot more to life than brains. Note that we share a third of an amoeba’s genes, regulating many of the critical nuts-and-bolts functions of our cells. We share 60% of a banana’s genes. Only 0.5% of biomass is in animal form, and not even all animals have neural centers that qualify as brains. Yet, that tiny sliver of life boasting brains could not exist without the much larger and more diverse (spectacular) brainless web of life existing alongside. Because many of these species have been around much longer than us, they know more than we do where it counts. Their knowledge might not be processed by neurons in a cerebrum (a recent trick), but is still unquestionably present and robust. Brains are just one way of knowing, and not the dominant one, or longest-lived one, in fact.

Consider also your own body, where perhaps 2–3% of your mass is brain meat. Yet the brain would be a useless lump without the heart, lungs, kidneys, stomach, pancreas, and all the rest. There’s much more to being human than having a brain, and much more to life on this planet than the few species that happen to utilize the brain adaptation.

Humans hold up brains as the most important attribute. Is it a coincidence that this just happens to be our most heavily-invested niche, in evolutionary terms? What would a bat think defines excellence? What would a snail define as the ultimate quality, or a barnacle? Silly goose: these animals don’t bother defining anything at all (a cerebrally-biased habit of questionable value), and are arguably better ecological citizens for it.

Don’t Let it go to Our Heads

My main point is: just as our culture misplaces value in money, we misplace value in brains—in a transparent display of ugly self-flattery. We’re the insufferable billionaires of the brain sector. Human brains are a very new experiment on the planet, which appears to be driving a sixth mass extinction, presently. Time to reign it in. Let’s not double-down and soothe ourselves with empty stories that we can solve any of our mounting problems (of our obvious unwitting creation) with more brain-driven innovation and technology (brain-farts, as I’ve taken to calling them).

Now, are our brains capable of self-deprecation, or did evolution produce an organism only just capable enough to produce great harm but not capable of self-limitation? Well, some cultures deliberately crafted self-restraining customs and stories, so I don’t believe we can rule out living responsibly. If we are to succeed for the long term, it won’t be in a style that looks like modernity, but will most likely have great overlap with the ways of other beings who have proven their longevity on this planet. Rather than exalting brains and our thoughts, a successful human culture will be suspicious of where these narcissistic, unconstrained, decontextualized shortcut machines might lead us, if left unchecked.

[Note for subscribers: Last week my gmail test account put the Do the Math newsletter into the “Promotional” bucket. You might check your own, and persuade your mail client to accept these mailings as “legitimate.”]

Views: 2902

"Rather than exalting brains and our thoughts, a successful human culture will be suspicious of where these narcissistic, unconstrained, decontextualized shortcut machines might lead us, if left unchecked"

There are too many questions, with no answer, about the brain.

Do you think of a different checked kind of brain for other beings?

How independent its work is from the microbioma?

Our brain is clearly, I think, a technological might.

This allows the spicies to arrange too many things in order to keep confortable and successful in a changing world.

We have the bias of adding elements to get to the solution of a problem, when logically is better to eliminate elements, to simplify the problem.

This strong pressure creates a much more chaotic environment.

We love aporía, discuss about the sex of angels, but we have some kind of contempt to our integration with the rest of life in this world.

At the end I'm afraid that using a simplify model could be most understandable for our shortcut-machines (except for solving problems), and this is thinking of cancer.

Cancer in a body behave like humanity in the world.

A bee can't explain the behavior of the colony,

Can a person or a brain explain the behavior of humanity?

Maybe the superorganism is not the same as the individual.

Doing the math we are more a micro life carriers, than autonomous individuals.

https://www.microbiologyresearch.org/content/journal/mgen/10.1099/mgen.0.001322

One does not preclude the other.

Of course not.

But helps understand how "narcissus" humans are.

All living forms are microbial life carriers, and you're right.

Reading made me think about the very concept of "life"… The boundaries are quite blurred, as in many other "exercises of the mind". Big Huge! Colossal!!! the wisdom of complex to understand, but simple to feel, "concepts", of NON-Western indigenous peoples seems amazing… This method of "contemplation, feeling and experience" seems to have given communities meaning, gratitude, humility, care, and a sense of "grounding". Literally. We are totally spoiled.

We seem to be entering a period (the Enshittocene) where the likes of garbage-in-garbage-out-type AI (set up, run and interpreted by humans with infinite growth mindsets) are seeing us more rapidly approach the logical end-point associated with inhabiting a defective human mental model of the world rather than the real world.

I hope/pray that this somehow miraculously lead to a major tipping point where huge numbers of people simultaneously realize, "Hey, this is where stupid human thinking, including my own, gets you!". Maybe witnessing MAJOR jamming of the cogs that run the human modernity machine is what is required to initiate meaningful change? I don't think "prophets" or words will cut it, sadly.

But maybe entering the Enshittocene will just see us destroying what's left even faster…

Still, my hope is that the phenomenon of exponential-like enshittification might somehow serve as a grand-scale wake up call, rather than being the final crescendo that finishes us humans off, along with the majority of our current earth-others.

But I really have no idea how it's all going to pan out…

Thanks for another great essay. I totally agree about human supremacism, with its emphasis on brains ('intelligence'). Intelligence is not needed to describe truth, but to invent lies.

How do we ascertain ('left brain') facts? By experiments in the physical world. This is what's now known as science.

How do we accrue ('right brain') wisdom? Not in the same way. Both types of knowledge are aspects of reality. Both are useful.

Science's mission, at first, was to study the works of 'The Creator', and it was subject to ethical constraints. Over time, it became completely secular – and amoral (see nuclear weapons, guns, bombs, chemical and biological weapons, vivisection, genetic manipulation, mass production etc etc).

Now, modern science exclusively serves the bureaucratic, corporate machine-State.

As we strolled down the road of knowledge, science and wisdom were acquired at roughly the same rate, but soon scientific knowledge grew exponentially, rapidly outpacing the other kind.

The difficulty many have is that this second type of knowledge must come from somewhere other than science. That is unacceptable to them – but it's true nonetheless.

It can't be codified, like science can.

Where does it come from?

What is the relation between yourself and the endless and infinite universe, or, its source and first cause?

Thanks James.

I think people are truly crying out for an understanding of the relation between self and the endless and infinite universe! I think that deep down we also want to feel that this relationship is important to the universe itself. Although we want to be exist as separate selves, we don’t want to feel alone.

Many insist that science/materialism is all there is to (explaining) reality. But what is most important at this stage? Humans understanding and appreciating the true nature and workings of reality (if materialism’s version is indeed all there is)? Or humans (re)learning, through some miracle, how to live in a sustainable fashion on this planet and respect the value of all life?

It may very well be the case that, in reality, brains/minds are overrated, that mind emerges from matter, and that everything ultimately comes down to tiny particles with only physical properties interacting with one another. However, in my opinion, more important than people necessarily accepting materialism’s facts is reinstalling a sense that the universe is a sacred thing/process and that it is truly all there is, so we should DEEPLY care about it (there is no “other side” or salvation to be had).

Can science/materialism really get us to a sense of sacredness? For some it definitely can, but for most present humans I think it is way too big an ask. The “how can we get life from lifeless matter?” question is just too big a hurdle.

We should be tolerating and seeking to provide the masses with as many attractive/stomachable routes out of the modernity mindset as possible.

Speaking for myself, the world is no less amazing without Santa Claus; likewise awe and respect for life are possible without needing to be important to the universe as a self apart from the corporeal. A sense of sacredness and caring does not require elevation of the self "above" materialism, but I get that it may not work for most people in our culture. I wonder how much of that is having been spoiled by a culture of human supremacy and control over nature to believe ourselves special. It's devastating for kids when they learn there's no Santa Claus, and perhaps even harder when dealing with a core sense of self.

It's a fair point that we may be better off working with what we've got, and maybe have a "training wheels" option for those not ready to give themselves to the mystery of the big gap, instead requiring a reassuring explanation that fits in their heads. On the other hand, the real change will be by generational replacement, rather than individual transformation. Will a child of the year 2500 require a sense of self importance, or will they happily accept a more humble station?

I'd love to know how humans 20,000 years ago thought about "self." Would communication on the topic even be possible given possibly divergent sensibilities? Since life for most was only possible in tribal relation, and survival of the tribe took on paramount importance (over the self), it may be that those ecologically integrated folks needed less reassurance of their importance to the universe, and embraced mystery. Perhaps this is the most common mode of living for all beings on the planet, and it is only recently that we became intellectually greedy.

Thanks Tom.

No argument from me that the idea of mind without matter (or a self separate to the corporeal) is like believing in Santa Claus. I can even accept that something like Garziano’s Attention Schema Theory might potentially explain the phenomenon of the “self”. But somehow I find the idea that, for example, the sensation/experience of color is an emergent phenomenon underpinned by the interaction of physical matter (and absolutely nothing more than this) akin to believing in Santa Claus as well.

I accept that my brain is very, very limited though, so I may eventually be convinced to believe in this real “Santa Claus” 🙂

To me, the sensation of colour is ineffable. But I will never ever believe anything that tells me it isn’t real.

Interesting "equivalency." I suppose one could say that any phenomenon or reality that is not fully nailed down (correctly) by a mental model might as well be magic, in a sense, and thus Santa Claus. I get that. And because our brains are incapable of a full grasp, the world will always seem magic. Then it might seem arbitrary which magic one chooses: no limits. Maybe. It feels different to me to assume a "magic of tangled complexity" as opposed to a "magic of mind, soul, god, etc." No new actors, influences, planes are required, placing all the magic in ignorance of material complexity (feels humble and accurate).

While I admire/enjoy the sensation, color does not particularly bother me the way it seems to catch philosophers in terms of "qualia." That's the brain's job: to ascribe identifiable qualities to sensory input so that we might sort, categorize, associate, act, seek advantage and avoid disadvantage. Red is going to make an impression for any organism possessing color vision and able to differentiate 650 nm from nearby wavelengths. I can't track the full neural machinery from reception to recognition and trigger of memories, but have little difficulty giving biophysics enough leeway to get the job done, without supernatural intervention.

(Personally, I never believed in Santa Claus even as a child…)

Human supremacy is indeed to blame for people feeling themselves to be 'above' the rest of the natural world. The modern world, and modern culture, is deeply rooted in this supremacism – and it includes the application of science to all areas of destructive human behaviour.

It seems to me that many people (including scientists), having left-brained the *** out of the world to the point where we're facing a sixth mass extinction etc, now lament the fact that we've lost all awe and respect for Nature.

What did they expect?

Whether or not science can give us a philosophical basis for sacredness shouldn't matter too much. People are quite capable of embuing all sorts of things with sacredness, and in an age when many people are moving away from trusting in science (a trend which has accelerated post-covid), a science based sense of the sacred may even be unhelpful.

Narrative truth and consistency may be more important than scientific truth when imprinting belief systems on minds and people don't like changing their belief systems.

So how to embue the natural world with sufficient sacredness, that we cease to destroy it and indeed help regenerate it?

I believe that most people already believe that it is sacred, but they feel powerless to make a difference. They sense that the super organism is too powerful and cannot be stopped.

Some commenters seem to reading something that isn't there –

I never mentioned sacredness. I never mentioned self.

Just asked a question: what is the relation between *yourself* and the endless and infinite universe?

This relation is important to the universe in no way whatsoever.

It's how *you* relate to *it*, not the other way round.

The point being missed is that there's a mystery at the heart of all existence. That's all.

It can't be explained by science. Maybe that's why scientists try to deny it so vehemently?

James said: "The point being missed is that there's a mystery at the heart of all existence." Truly. Lots of questions science can never answer, like "Why is there something rather than nothing?" Even the details of why our physics turned out the way it did (electron-to proton mass ratio; gravity to electromagnetism relative strength) may very well be unanswerable. I'm satisfied with: "because it CAN be this way," and why not feel lucky to experience it?

Apologies James. These were just my additions to the discussion. I will be more careful in future. I’d didn’t mean to speak for you in any way.

The comment that “This relation is important to the universe in no way whatsoever” seems a bit extreme to me. Do we each at not least not matter to our family? They are part of the universe.

"…because it CAN be this way…" is a perspective I've never considered. Thanks for that one, it clears away a bunch of noise for me.

It sounds like a version of Boulding's "if it exists, its possible."

Thank you for the fun read!

I couldn't help but wonder how this analysys would look like if one were to look at neuron count instead of brain mass?

Perhaps I'll run the numbers myself and shoot you an email if the result warrants it 🙂

The way I see it, our meat brains evolve at one, slow, rate, while our cultural evolution has advanced at a rush, a much faster rate. To be sure, for our hunter/gatherer ancestors, life was complicated, but nowhere near as complex as our life has become under our bewilderingly intricate culture. Our bio-brains can't keep up. Most of us don't have the conceptual horsepower. We prefer our left-brain's penchant for simplicity, so we overlook a lot, and reduce the world to a simpler story that we can handle. Unfortunately, that simpler story is wrong at key points, and in fact is turning out to be deadly.

Well summarized. We've always had a cultural overlay generated by brains, but for most of human history the overlay was tuned for compatibility with ecological realities—in some sense constrained by a form of selection to WORK long term. The current imaginings of who we are (separate, supreme), and what we can do (anything our unlimited imaginations conjure) set us up for colossal failure when the biophysical world finally makes a (slow) pronouncement on our incompatible ways.

Merci. Wonderfull food for …brains. Brains may be an experiment, a localized one, successfull on its own but a failure at scale. And therefore will either need to stay local/limited or adapt to fit in with the whole. To tell brains how modest they are, I would say that the _position in space&time_ of species and their organization are multiple orders more ‘hefty’ than brain-gray. These patterns led to brains and they are old and vast, as well as complex.

Thanks for the essay. Although human supremacy is a major factor in industrial civilization (IC) damaging the environment, I think that the struggle for status is just as damaging. The efforts of the super and hyper rich to accumulate more wealth and political power are overwhelming any effort to deal with the climate emergency (CE). An example is the recent elections in the United States where wealthy Silicon Valley types, in particular Elon Musk devoted considerable resources to elect Trump who will accelerate the CE and the decline of IC. A book I recently read and recommend is Status and Culture by W David Marx. One point it makes is a transition from previous markers of status to pure displays of wealth. Best.

One irony is that if the ultra-rich were to distribute their wealth to the rest of the world, we would see a surge of material conspumption, which would be very bad for the natural world. Sequestered money is not "kinetic."