Our prized cerebral capabilities at the level of awareness don’t stack up to very much when compared to the vastly-more-numerous-and-amazing capabilities of almost every other aspect of Life. The relatively meager mental capacity we tend to worship is in many ways the slightest addendum whose capabilities are comparatively rather modest. Yes, we have devised ways to lock in small gains and ratchet them into powerful forces, but the process is embarrassingly slow and limited compared to most processes carried out by Life.

The Impressive Base

The overwhelming share of what makes humans amazing operates far beyond mental awareness. Outside the sacred cerebrum, we breathe, circulate blood, digest a diverse menu of food, filter and clean internal fluids, eliminate wastes, heal wounds, coordinate movement, generate the cells for reproduction, build and rebuild ourselves from a cryptic blueprint, and perhaps most impressively solve very thorny open-ended problems of devising antibodies tailored to disable novel pathogens. For all their “massive” brain-power, the average living human would not have the first clue how to devise a functioning, fully-integrated replacement for any of these and thousands more tasks our bodies handle without a thought. Even the best teams in the world wouldn’t be able to pull it off (though would at least have “the first clue,” and in so doing would know it to be beyond their capability).

Now add the cerebrum and a whole suite of additional capabilities emerge—still beyond our awareness. Perhaps most stunning is visual processing. Among other attributes, it’s nearly instantaneous, seamlessly combines vision from two optical instruments, fills in gaps, enjoys excellent color representation, and has extraordinary dynamic range (putting our film/print or electronic cameras/displays to shame; it’s why total solar eclipses can neither be captured nor displayed adequately by technology). Add to this an incredible capacity for auditory processing able to differentiate subtle sounds and comprehend language. What’s easy for a two-year-old still stumps technological implementations. Our brains perform pattern recognition tasks that are light years ahead of what lots of investment and smart people have been able to cobble in crude technological form. Remember the self-driving car hype from about a decade ago? And the fact that captchas work at all is remarkable testimony.

Don’t ask us how we do it—we have no idea. We just know so many things that we can’t articulate or are not even aware of: we take them for granted—as must be the case when literally unaware of the underlying processes.

Unbidden, the Disney Jungle Book tune for “Bare Necessities” slid into my brain in connection to the “spare capacity” title and theme of this post. Maybe I should try a song version sometime…

Spare Capacity

I would guess that the extensive wiring in brains is mostly dedicated to the aforementioned real-time sophisticated capabilities that operate beyond explicit thought. All the same, our prefrontal cortex is cross-wired to many parts of the brain so that it can be (dimly) attentive to parts (distillations) of the process.

The main point is that the “aware” part of our bodily function is the tip of the tip of the iceberg. On second thought, I don’t like that metaphor because it aggrandizes awareness to some sort of ultimate pinnacle. Maybe its more like the freckle on the cheek (which sort of cheek is reader’s choice). In any case, it’s a small, spare capacity. If rated in some metric of operations per second (which must go beyond neurons firing, since many of our internal miracles do not utilize neurons), the part of our process we call conscious thought must account for a very small fraction of the whole. Again, it’s a spare capacity—simultaneously employing two meanings of the word: “extra,” and “slight.”

To put the spare capacity in perspective, first consider the aphorism that a picture is worth a thousand words. What we perceive visually in a split second accomplishes more than can be expressed in seven or eight minutes of language (taken literally). Moving beyond cliches, some science hippies at Caltech (as Ze Frank would lovingly call them) quantified the processing speed of humans in both thought and sensory processing. Thinking proceeds at a ballpark rate of about 10 bits per second (10 Hz “bandwidth”), whereas sensory processing is in the range of a billion bits per second (GHz). Thinking is 100 million times slower! That’s pretty darned “spare.” Thought is also very serial: one-track. Our bodies and other brain functions, however, operate in a massively parallel mode. Talk about a bottleneck!

Granted, a fair bit of machinery operates underneath thinking, in support of the awareness level. But the final product—the part of which we would say we’re consciously aware—is rather slim.

In my own crude approximation, a 2,000 word Do the Math post takes about 12,000 bytes (100,000 ASCII bits) of uncompressed HTML space, or maybe a quarter or a third of this in compressed form. I could easily argue that words are “stored” less cumbersomely in our brains than spelled out bit-wise, so that a vocabulary of 8,000 words (stand-alone nuggets) can be addressed by 13 bits, in which 2,000 words involves 26,000 bits to address. Hey: very similar to the compressed value. If read over about 12 minutes, we’re at 36 bits per second: in the order-of-magnitude ballpark of the Caltech study (around the high end of their varied assessments for many task types). [Actually, our storage is likely more efficient, effectively indexing more common words using fewer “bits.”] This example is actually a hyper-compressed version of delivery: truly internalizing as you go—experiencing the parent thoughts—takes longer, and developing the thought in the first place took far longer, even.

For another perspective, how many truly novel epiphanies or profound realizations does a person have in their lifetime of thought? Even if occurring at the hyper-prolific rate of one per day, each requiring a blog-post-length exposition to convey (when a few sentences might actually suffice—apologies!), we’re talking about 0.3 bits per second. Drip…drip…drip…

Severe Limitations

In last week’s post, we looked at how our spare capacity stacks up to the complexity of even a “lowly” microbe by considering the prospect of designing Life. Not only would we fail miserably—using our brains—to invent a viable form of Life, we couldn’t even expect to make from scratch a single protein to perform some novel function not already worked out by the über-genius of Life. Forget the multitude of proteins required by a cell, their myriad interactions, and the even-larger job of sensible regulation.

Life is made of extraordinarily complex arrangements that exceed our design capacity by such a tremendous gulf as to be ridiculous—triggering many to engage in dubious “god-of-the-gaps” style speculation to paper-over the scary gulf.

Persistent Penciling

Despite the surrounding ubiquity of Life’s amazingness, examples of what we are woefully incapable of doing are rare in our culture, as the focus tends to be on what we can do that’s amazing. We do indeed design contraptions “from scratch” that allow us to perform feats we otherwise could not—however inelegantly—like flying or breathing underwater or computing the square root of pi in a split second. I again stress how pale these inventions are when stacked against even an amoeba, as they cannot reproduce, self-heal, fight disease, or evolve. Nonetheless, here we are with cities, cars, airplanes, scuba gear, and smart phones.

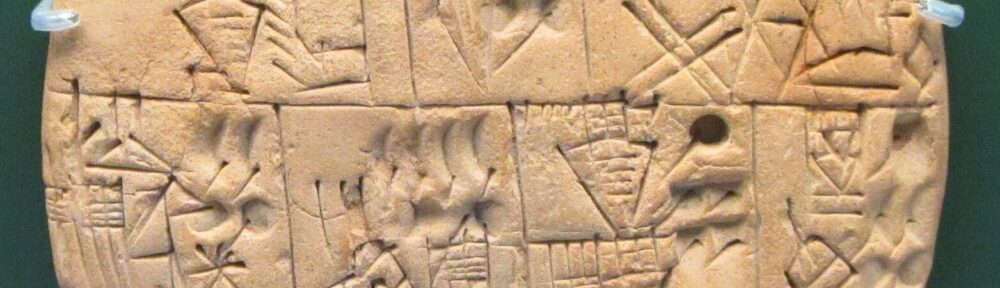

The main trick we employ to effect such accomplishments is symbolic, written language. We “lock in” crumbs of thought and connect them. I can’t tell you how many times I have attempted to work my way through a tough problem without access to some means of writing or drawing. It’s nearly impossible, exceedingly slow, and error-prone.

Even with implements of writing, the process of working through a difficult problem is extraordinarily slow compared to the “real time” processes of our brains (e.g., visual processing; pattern recognition). But, our ability to break down the problem into smaller and smaller steps, committing each to semi-permanence—outside our brains, importantly—allows us to leverage and ratchet this spare capacity to a tremendous degree. The accumulation of paper-thin steps can stack quite high given enough of them.

Outsized Impact

Obviously, I should not completely dismiss this spare capacity, as it clearly has the power to upend an entire planetary ecology on timescales that are lightning-fast compared to those of evolution. But, identifying this core “trick” helps me reconcile how an incremental cerebral capacity translates to a “quantum” leap in its expression: a nonlinear threshold phenomenon. Chimps do not make skyscrapers or rockets or smart phones (nor have most humans who have ever lived, either, if we’re being honest). Chimp inventions are perhaps millions of times less sophisticated than a computer. Yet, it’s definitely not the case that human brains are millions of times larger or more complex than those of chimps, and in fact human brains today appear to be smaller than they were 10,000 years ago.

We have clearly made “the most” of this spare capacity, and I strongly suspect that written language plays the primary role. What it does, effectively, is captures pieces of thinking—selected for “worthiness” (logical consistency, utility, etc.)—then makes them available to be “hooked up” to other written thoughts. Written/drawn records become a sort of externalized and shared brain. The actual, raw mental capacity devoted to these pursuits can be as spare as you like. Reminiscent of an enzyme’s action, as long as we are able to hold a few pieces of this externalized knowledge together at the same time in novel combinations, novel knowledge/capability can emerge and get locked into written/drawn form. A type of selective evolution preserves the “successful” ideas and discards the more numerous idiotic ones. The process can be glacial compared to real-time internal brain processes, but by virtue of preservation, no longer has to be “instantaneous.”

Overemphasis

Obviously, we put great stock in our accumulated knowledge. Libraries (and digital equivalents) form a sort of super-brain—though incapable of thinking on its own (so far). When we say that humans are smart, we really refer to this external bank and our scraping capacity to access/process it. An individual member of modernity pulled aside and deprived of access to this bank (and the derivative tools) will be incapable of doing almost anything we consider to be technologically impressive: perhaps unable to even start a fire or find edible food. Nor could they likely explain much of the accumulated knowledge “off the top.” A hunter-gatherer pulled aside, by contrast, is likely to personally possess the majority of (non-trivial) knowledge upon which their lifestyle is based: they have to.

Meanwhile, I keep emphasizing the genius of Life. Plants know when it’s safe to put out buds; which year is good for fruiting; how to fend off intruders and alert others; and—let’s not forget—how to turn sunlight into sugars, for gods’ sake! Birds weave elaborate and sturdy nests out of materials at hand that survive the winds and rains and jostling chicks. Give a person a table full of the same materials and even allow them to use all the spit they wish and you won’t get anything as functional. Examples abound of genius capabilities in the living world, learned and honed over deep time.

We discount such “genetic” genius, even if it dwarfs our own spare (even written) capacities to a staggering degree—accomplishing feats that utterly baffle us. We have this external repository, and that’s what counts as genius, by golly. Yeah, and it’s also driving a sixth mass extinction, so huge pat on the back, there.

Oral Tradition

This is a bit of a new line of (characteristically slow) thinking for me, though obviously well-connected to the previous snail’s-pace train of thought I’ve been riding—which of course I have written down. I’ll be contemplating the relative importance of agriculture—when some humans broke from ecological life and donned a conquering, controlling mindset—and the subsequent development of written language—when we cemented techniques, established accounting/money, and concocted written laws. The rest, in a hyper-literal sense, was “history.” But perhaps it’s foolish to pretend that agriculture and writing are separable phenomena, as perhaps the first is bound to lead to the second in short order—as actually happened.

Spoken language has, of course, been with humans since humans have been on Earth. Oral traditions dominated transmission of knowledge. This important capability in itself gives humans enormous leverage. But oral traditions are more fluid, evolutionary, malleable, form-fitting, shaped by feedback in terms of applicability/relevance, and thus “alive” in many regards—almost as members of the Community of Life in their own right. Is oral-only communication intrinsically better? Is that form of language inherently more ecologically compatible? Is use of our spare cognitive capacity to commit thoughts and stories to rigid permanence itself problematic? It’s certainly new, and we’re entering a sixth mass extinction, so circumstantial evidence is not smiling on the case. Conversely, spoken language failed to threaten mass-extinction for millions of years, so might get an ecological pass.

But obviously I don’t know, we don’t know, and we probably can’t know if writing is a bridge too far: our spare capacity isn’t up to the task, as usual. Only the ultimate arbiter that rules on evolutionary cases can speak to the matter, in its slow and inexplicit manner. Preliminary courtroom revelations, however, are not reassuring.

Views: 569

Oh, you haven't added another layer of complexity. Interaction between individuals. It's amazing how easy it is for swallows to teach their chicks to interact in a population. How incredibly and imperceptibly and naturally other animals communicate with each other. And what difficulties arise in the most intelligent species on the planet.

Killer whales also think, but communication and communication are more important. Sea turtles unfailingly return to lay their eggs on a beach where they have only been once – when they themselves hatched.

In nature, bright color, shine, or contrasting unusual structures indicate danger. But in human culture, anything that shines is associated with value.

Teaching children? I think we deeply suppress the innate abilities to observe, imitate, and repeat. (This point is written without any intention to offend or discriminate) I saw a Roma child who so subtly understood the inner state, motivation, desire and, it seems, even the decision made, even before I said a word, just by looking into his eyes. He was not even 6 years old.

Thank you for the post! 🙂

Roughly speaking, the number of "tuneable" parameters in the human brain scales with the square of the number of neurons. Conversely, for computational models, the approximate neurons effectively simulated scales with the square-root of the number of tuneable parameters. The upshot is that even our most sophisticated computational toys, such as LLMs, with roughly one trillion tunable parameters are really only simulating about one million neurons, or equivalent to the average bumble bee.

Now here is where we hit some real limits. The energy consumption of silicon based digital computing scales exponentially with the number of parameters, albeit slowly, due to the curse of dimensionality. This stipulates that to simulate a modest human brain using silicon digital computing would require the entire energy in the visible universe multiplied by a number with 100 digits.

One small addendum: a few pre-contact nomadic, foraging, and pastoral cultures in North America had written language

Cool posting Tom! You do a great job of getting us to think. And since I'm the crazy fire guy, I'm obligated to cram in a shameless plug for fire. (using some AI help for the following… I know, I hate people who use AI to sell their bullshit ideas. But I'm gonna do it anyways. LOL)

"Spoken language has, of course, been with humans since humans have been on Earth."

It has? If we're talking about general vocal communication, grunt like sounds, then I'm with you. (and maybe I'm taking you too literal just so that I can tie it back to fire😊)

Fossil studies suggest Homo Erectus vocal tracts may have been more ape-like, which would have limited the range of sounds they could produce. The rapid and fine-grained motor control needed for speech articulation is facilitated by direct connections between the motor cortex and the vocal tract in humans. Modern human speech relies on a lower larynx and the ability to control and shape the vocal tract.

The evolution of the human vocal anatomy, including the larynx, played a role in spoken language. In essence, fire created a social and cognitive environment where the ability to communicate effectively through complex vocalizations was highly advantageous. While the specific anatomical changes in the larynx and vocal tract were driven by genetic mutations, fire may have played a significant role in creating the selective pressures that favored these changes.

Some researchers hypothesize that fire played a role in the evolution of the human brain, which is necessary for language and complex social interaction. Cooking food over fire made it easier to digest, potentially providing more energy for brain growth. The cognitive demands of managing and utilizing fire, such as understanding cause and effect, planning, and teamwork, may have also stimulated cognitive development.

Based on recent genetic and archaeological evidence, humans likely had the cognitive capacity for language at least 135,000 years ago and began using it widely for social communication around 100,000 years ago.

Earlier this month Derrick Jensen recorded a conversation with me for his podcast about the inventions that precipitated the current mass extinction that we've kicked off. Fire made my "provisional" list. I've written an accompanying post that will come out in another month or so.

When thinking about the dynamics that get humans into a state of ecological overshoot, the kernels that lead to that state seem to stem in part from having population densities above Dunbar number tribes, ~150 individuals give or take. – The population context in which we lived for hundreds of thousands of years as a species (or millions as hominids).

Once a population density exceeds numbers where everyone knows each other through direct meaningful relationship, artificial schemes designed to 'manage' such populations start to emerge. We can never quite get our schemes perfect however, whether it be governmental structure or economic rules, our constructs invariably fall short, being divorced from biophysical reality (not least because we don't fully understand biophysical reality). In this framing, things like governments, economies, destructive technologies (included writing), codified laws, powerful militaries, and other human constructs, up to and including what we call civilization itself, are all deleterious symptoms of population overshoot (which inexorably leads to a state of ecological overshoot). Of course, food makes babies, so all of this ties back to the adoption of agriculture.

Can governments and economies and our technologies themselves be early symptoms of overshoot, the stuffy-runny nose before the fever sets in?