Two posts back, we discussed common objections to the materialist (monist) perspective, before visiting the idea of material sentience. Another form of objection is to label such views as “reductionist.” The thinking is that claiming Life to be “nothing but” matter is not only a staggering simplification, but also reduces the amazingness of life to mere “dead” physics.

But see, not only is the “dead” part dead wrong (animated interactions never rest!), the objection itself requires a fundamentally dualist perspective: asserting/fabricating a hierarchy and division between Life and matter as a non-negotiable starting point. If the concern is that Life is devalued by comparing it to (or even further, saying it fundamentally is) “just” matter, the problem is in concocting a dual valuation in the first place. Why not say the entire singular phenomenon is amazing? Maybe the problem is in denigrating matter. What’s the equivalent of “racist” when it comes to matter? I guess “dualist” will do.

Thus, we may appreciate how “sticky” dualist beliefs are. Without truly inhabiting a non-dualist viewpoint, any materialist approach seems reprehensible from within that biased framework. Lots of belief systems feature similar mechanisms to quell questioning or discourage straying far enough from the path that the path begins to seem janky.

Reduction Everywhere!

Firstly, to live in the universe is to be a reductionist. To sense and react is to represent some aspect of the world in a simplified way and respond according to thresholds. To have a brain is to make flawed and woefully-incomplete mental models. Everyone is a reductionist. We’re quite happy to accept that the sun is a star, that snowflakes are made of (identical) water molecules, or that oxygen is the component of air we need to breathe and live. We don’t blink at the reductionism of integers or addition. The Periodic Table doesn’t get criticized as reductionist in preference to an uncountable number of elements—no two atoms alike (assuming they’re even real!).

Most people are perfectly happy to divide life into a collection of species and phyla, or to draw a sharp line between animate and inanimate, inner and outer, subject and object. These are highly reductive acts, but such is the price for making limited sense of the world using a limited meat-brain. No one escapes the label, but this doesn’t by itself imply complete equivalency.

Or think about language as a scheme to reduce the messy analog world into a digital (discrete) representation using a relatively modest number of words. Or going even further, the complete works of Shakespeare, or the Bible, or the Encyclopedia Britannica, or those and many more combined can be reduced to 26 letters (in English; far fewer suffice in other languages). Letters are like the atoms of written language, and the small count hardly matters in terms of how expansive their combinatorial use can become. Importantly, just as for atoms and molecules, interactions between letters determine valid expressions—or else we’d sift through random garbage like “OknjsYTJvrPTE, sBdHV” all the time. Arrangement matters, for both letters and atoms!

As expressed in the previous post, labels do not change the actual world we experience, so that a marmoset is every bit as adorable and well-adapted whether or not we believe interacting atoms are sufficient to produce the result. Materialism need not remove “specialness,” although doing so across the board does have the side benefit of combating supremacism. Placing everything on the same footing can be accomplished by either “demoting” Life to “matter status” (a dualist dichotomy from the start, and a stubborn sticking point for recalcitrant dualists) or elevating the whole singular phenomenon—which gets my vote, for what it’s worth.

Since it often seems to go unappreciated, I’ll hammer this key point again: adopting a position that all we experience is built on matter and its interactions is not the same as offering a tidy, complete, settled explanation for how it all works. In fact, it’s sort-of the opposite. It’s simply a position that nothing more is required at the most fundamental level: we needn’t be greedy, and we needn’t make up stuff to paper over our ignorance. Ignorance is okay! It’s inevitable! Nothing to be ashamed of… In light of this, limited cognitive capacity to connect all the dots constitutes insufficient grounds for rejection: we are not gods.

In other words, and relevant to the charge of reductionism, don’t confuse a simple foundation for a simple explanation. Limiting to 26 (or fewer) letters does not in itself translate to a comparably small set of possible language expressions. Indeed, this particular paragraph—or even this sentence—has probably never appeared before, without once utilizing exotic letters. Materialism amounts to a position of incomprehensible complexity rather than an attempt to “explain” it all in shortcut (reduced) form. It’s a humility of the unknown; an embrace of uncertainty. The fact that matter is observed to arrange in such a dizzying array of configurations and interactive sophistication blows our minds. The universe gets up to tricks beyond our wildest imaginations—all possible via a core set of actors and interactions. Facetiously, it’s like Taco Bell: able to fill out a menu of dozens of items based on four ingredients. How do they do it? The menu (the universe) is no less tasty as a result.

Who’s the Reductionist?

For many, the fact that no one can offer an end-to-end account for how Life and consciousness arise from quarks and leptons (and of course all the interactions between them) is taken as invalidating the premise. But think of what this means. Consider the arrogance; the impatience; the assumption of mastery. The fatal flaw is more easily attributed to cognitive incapacity (of humans as a species) than to illegitimacy of a materialist view, right? I mean, let’s be honest with ourselves on that point. Odds are, we will never understand the full story, but how on Earth does that translate to cause (or “legal standing”) for rejection?

The poetic irony, here, is that rejecting the incomprehensible complexity of conscious experience as emerging from material interactions is perhaps the most reductive act imaginable! Labeling it “consciousness” and declaring it to be its own irreducible phenomenological “substance” (thus already reduced to an extreme) is cutting a huge corner, like attributing to “God” any phenomenon whose origin is less than obvious. Is it cheating? For me, it robs the phenomenon of Life of its full splendor, sweeping the amazing (incomprehensible) part under the rug in hasty retreat.

Materialism takes the “irreducible” amalgam called “mind” and explodes it into hundreds of billions of cells, hundreds of trillions of synapses, and an enormously larger number of atoms and physical (mainly electromagnetic) interactions—not in fact confined to the meat-brain, but involving participation by the rest of the body and even the surrounding environment. How does this explosion shrink “mind” to a simpler notion? Where’s the actual reduction? Maybe instead of “reductionists,” materialists ought to be accused of being “expansivists” or “explosionists” or “complexinistas” or something in this vein that more accurately captures the position.

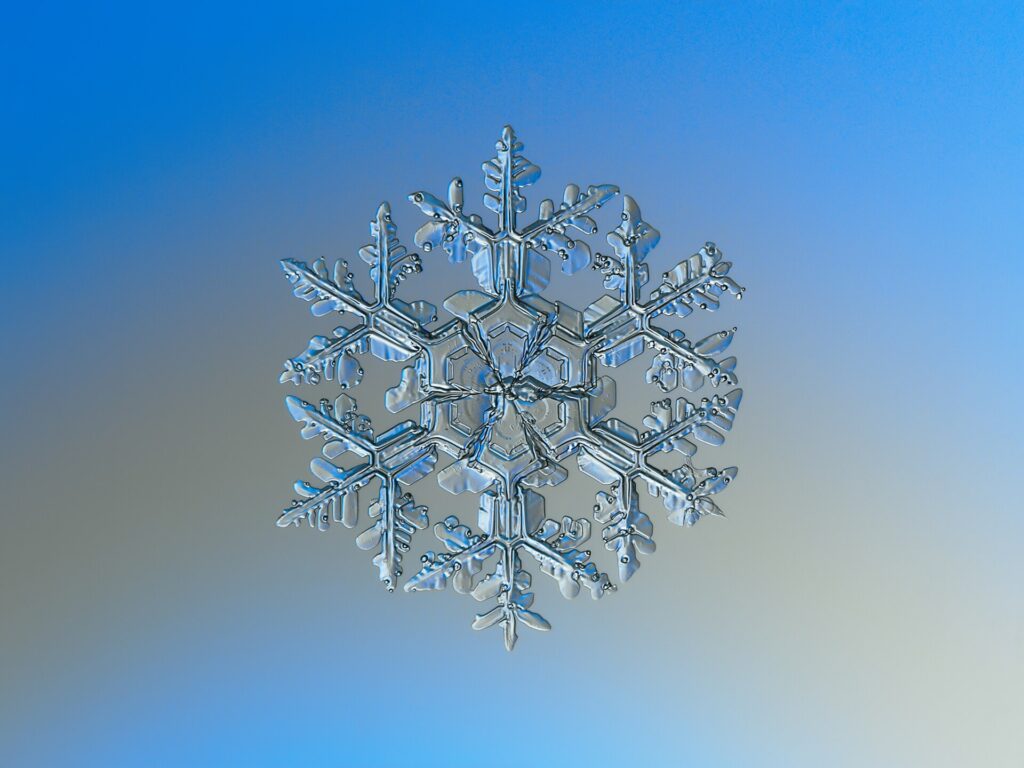

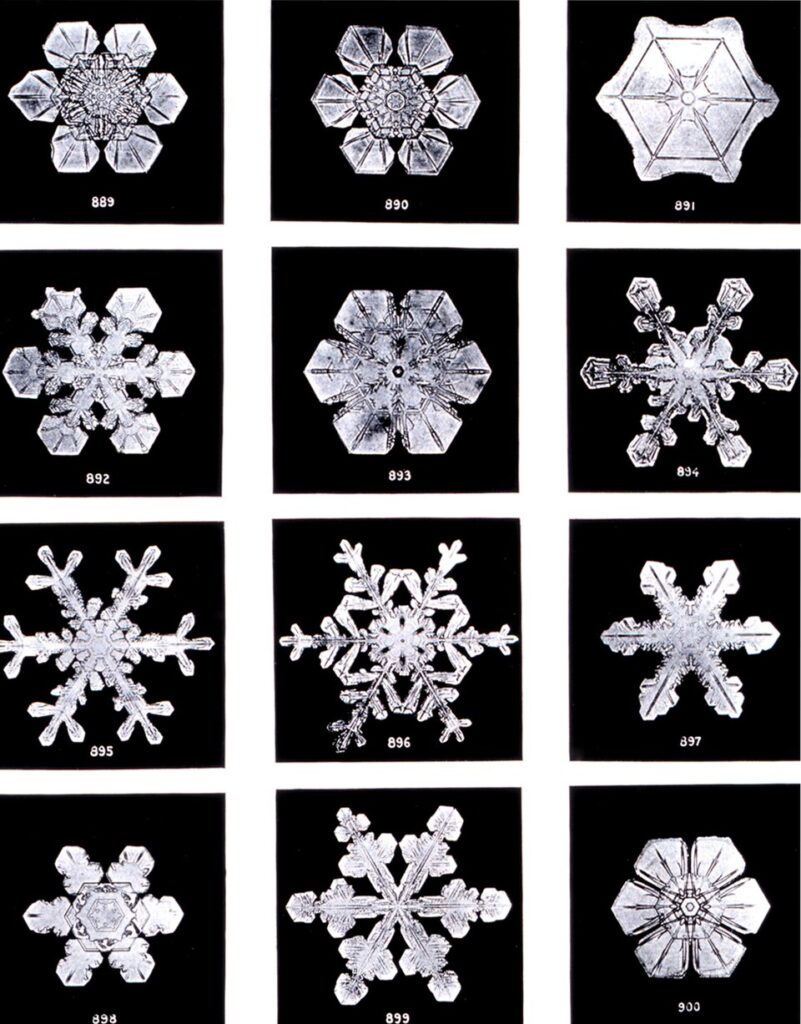

The small number of unique actors or fundamental interactions involved isn’t terribly relevant to the staggering complexity that can manifest, and may constitute a trip hazard for those who have not invested in exploring how physics works. The properties of water bear little resemblance to those of the nuggets that comprise it, and snowflakes can acquire stupendous intricacy, uniqueness, and symmetry even though the same water molecule is behind it all, in great numbers.

Given the explosive complexity involved, the “reductionist” charge rings as a hollow playground taunt, coming as it does from reductionist dualists.

Breaking the Symmetry

It would, of course, not be surprising for someone who is not a materialist-monist to characterize “it’s all physics” as being equally—if not more—expedient. But I perceive several fundamental differences. Mainly, we have a universe of evidence for atoms and their interactions in every single phenomenon we investigate: from galaxies to hurricanes to DNA. We indeed find that living beings are composed of said atoms in arrangements whose sophistication mirrors behavioral sophistication (consistently traceable when techniques allow). Why the close correspondence? Mere inconvenient coincidence to be brushed aside and ignored? The other key difference is that the materialist proposal isn’t slapping lazy labels on complex phenomena, but suggesting that undiscovered (normal-physics) intricate relationships underlie every observation, which in principle could be ascertained—and sometimes are. Not being “there” yet is more about complexity and capability limits than indicating some fundamental (unsupportable) reason why it cannot be so.

In ascribing all the glorious phenomena in the universe to a physics core, the point for me is not to rob Life of splendor (can’t be done: it is splendid whether or not we can explain it), but to create a space in which splendidness can emerge by the universe’s exploratory hand without requiring our cognitive approval. I mean, isn’t anything beyond our imaginative capacity—like how fundamental particles/interactions can conjure Life—automatically grand? It would be hard to do any better! Demanding full comprehension based on our limited brainpower cheats the universe of its potential brilliance: chaining it to our mental constraints. It’s essentially a form of loud protest over the notion that the universe might possibly be smarter than us: able to figure out tricks that defy our comprehension. But isn’t it obvious that it does so constantly? Each incremental discovery verifies that it’s been ahead of us the whole time as we scramble—often in vain—to catch up, only scratching the surface as we try.

When I think of the reductionist aspect of materialism, of course I see some point to it. Narrowing all experience to a small handful of particles and interactions constitutes an impressive feat of reduction in some sense (I would say on the part of the universe, not by me or other humans). But that’s looking only in one direction. Once comfortable with that position, the expansive opportunities that can can explode out of this foundation are beyond imagining. The situation is sort-of like a cone, reducing down to a sharp vertex. Peering into the cone and noticing that it all (somehow) looks as if it comes to a point might be called reductionist. But from that vertex, just turn around and look at the infinite “expansivist” cone that can blossom from there! The anti-materialist likely doesn’t protest the reduction to three macroscopic spatial dimensions as the stage upon which all experience plays out, or a small cast of letters (or sounds) from which words are constructed. Certainly they do not protest reduction toward irreducible concepts like consciousness or categorical distinctions like animate/inanimate that in reality are not crisp. Why, then, protest a small handful of material actors and rules, when every experiment points that way? Whence the hangup?

We Can’t Know

I spend a fair bit of time denigrating mental models as shabby representations of a more complex reality, fully aware that I, too, have no choice but to construct mental models of my own. This opens plenty of opportunity for the pot calling the kettle black.

Landing on materialism is easily painted as a limited mental model that is not capable of full and explicit representation of reality. True enough. Clinging to such an appealing model would seem to serve an emotional need for tidy simplicity—especially if one’s view is that materialism is a grossly simplified “Lego” model of the world.

This is fair to a point. I am indeed attracted to the bare-bones elegance of materialist monism: no need for invisible “magic sauce” to explain our experience of consciousness: the magic of materials is quite beyond full human comprehension all on its own. I am captivated by what these simple rules can get up to, much like the rabbit-hole captivation people experience when first exposed to the Game of Life.

But the symmetry is not total. Materialism also acquiesces to unthinkable complexity. It surrenders the requirement that we possess end-to-end accountability, living instead with ambiguity and uncertainty. Confident assertion that consciousness cannot emerge out of matter does not strike me as being tolerant of ambiguity and uncertainty (and where is such sure knowledge acquired?). Importantly, material monism is not claiming to have a model for how it all works; not pretending to understand; not demanding certainty. Rather, it is comfortable with not-knowing—submitting to complexity, while still respecting and acknowledging that atoms are found wherever we look and no violations of physics have been exposed in living beings or otherwise.

This mountain of evidence also breaks the pot–kettle sense of symmetry. I am not aware of any evidence (not counting opinion) that material is incapable of generating conscious experience. Idealism or dualism—claiming mind/consciousness to be a phenomenal reality not emerging from matter/interactions—is not based on evidence but on a feeling: that it’s irreducibly “like something” to exist (again implying it’s already been reduced as far as it can go into distinct consciousness and matter categories, for instance). Meanwhile, the universe is free to express relationships that exceed our ken.

In a key sense, the materialist monist is not attached to a specific mental model for how it all works: just a general commitment to the reality and complexity of material interactions—as witnessed. I suspect that those insisting that consciousness cannot be of material origin are much more committed to a mental model that allows less ambiguity and is less tolerant of not-knowing.

At the risk of being pedestrian, we can’t ever expect to know the truth, just as one can’t prove that the whole affair is not managed by invisible, miniature pink elephants wearing tutus while dancing on the head of a pin. None of these positions are provable, so we’re left guessing. I find merit in picking the simplest foundation requiring the fewest novel entities that is in principle capable of doing the job, while—and this is tremendously important—being consistent with all empirical evidence to date. As a bonus, the result is spectacular!

Maybe more to the point, I trust the universe more than I do the output of human brains. When we listen to the universe, it consistently delivers every message in material terms, using a surprisingly small set of actors and interactions. If I’m being reductionist, it’s only because the universe shows every indication of having beaten me to it.

New Physics?

One caveat deserves mention. Can I claim that we already have all the fundamental elements of physics in the bag? I would be foolish to do so. Fame-hungry physicists around the world are working non-stop trying to tear down the physics we know, seeking novel foundations or even paradigm shifts. It is almost certain that we’ll never have the full story.

That said, almost all the physics we know today—and especially the part most relevant to Life—was already in hand 100 years ago. Electromagnetism, general relativity, and quantum mechanics have survived a century of aggressive scrutiny (thus incredibly strong by now). Shrink to 80 years and we encompass nuclear forces and neutrinos. We’ve known about the three generations of quarks for about 50 years. These later developments involve rare or barely-interactive particles, so that the chances they play any key role in Life is pretty slim (never say never, but no apparent need to require them).

In other words, we have no credible reason (opinions/desires aside) to believe that Life as we know it and experience it requires physics beyond that which is already known. Now, might some life somewhere exploit physics not yet known to us? Just try and stop it! But is it crucial to Life writ large? We can point to no compelling reason to believe so, other than our own ignorance.

Dualism in Physics

Lest confusion arise over this point, I’ll take a brief moment to address various dualities in physics, like wave–particle duality, dual pairs like momentum–position, energy–time, and angular-momentum–direction that show up in both the Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle and Noether’s symmetry–conservation associations. Also the AdS/CFT correspondence/duality crops up. All cases actually draw deep and inseparable connections between what initially appear to be dual properties, but actually are conjoined aspects of a single phenomenon—like two sides of a coin—neither of which could exist without the other. Each points to a oneness/merging rather than irreconcilable divorce. So, dualities in physics actually argue against dualism in the philosophical sense, erasing ontological divides. It’s a case of unfortunate nomenclature, perhaps. But before you ask whether mind/matter might be dual aspects in a similar way, the parallel is not at all strong outside of word-thinking. One can’t even contemplate momentum without position no matter how simple the system, whereas consciousness is better appreciated as emergent in highly-complex arrangements rather than a part-and-parcel requirement at the tiniest scale of material existence.

The Wrong Tree?

In writing this (long) series, I may stand in violation of my own advice to meet people where they are, and gently guide them into a new space. Sounds great, but I’m not that talented at following it. Ingrained (and typically unacknowledged) dualism is deeply woven into our culture and language, so coming out swinging against it is unlikely to work well.

My goal here is to aim toward a sense of oneness; of animism; of gratitude; as lucky partners on this orb. We are one with the sun, rocks, mountains, rivers, and Community of Life. We’re all made of the same stuff and following the same rules, exchanging bits of ourselves all the time.

I happened to find a route that respects what we’ve learned—albeit by a destructive process that I might prefer had never happened. Whatever. We’re here now, and can’t put the genie back into the bottle. I can’t pretend there aren’t atoms and interactions everywhere we look, accounting for every process we’ve ever been capable of exploring deeply enough.

But, it’s not for everyone. For some, materialism—I would contend based on an inaccurate and impoverished comprehension of its contents—will seem sterile, distasteful, and carry (unnecessarily/inaccurately imposed) moral implications based on a culturally-reinforced dualistic sense that matter is relatively worthless, next to consciousness: material racism.

The question for me is: can we achieve the humility and oneness I believe we need without defeating the supremacy of dualism (including panpsychism) or the specialness of idealism? Maybe we can, and I can certainly hope so. It’s not my preferred route, as both retain a deeply problematic sense of separateness. On the other hand, it is a common perception that materialism is responsible for our history of instrumentalism and ecological harm. I would argue that this is actually the material aspect of dualists, who after all dominate modernity. Only within an asserted hierarchy of value is instrumentalism even “a thing.” In any case, the path hasn’t been pretty, and the material aspect of dualism tends to catch all the blame. The question is whether an animistic materialism (what I called unimism in a previous post) that seems more rooted in the reality of the universe is better than fabrications that risk preserving a hierarchy. I can’t really know.

Maybe we would have been better off as a species and as a whole Community of Life had humans not plowed down this row. But we’re here now, and might at least try to make lemonade out of the numerous lemons we’ve produced. We can turn science away from the adolescent job of smashing nature’s artwork to see what bits are inside and toward appreciation of the incomprehensible whole that emerges from said bits when left to their own. Maybe we can suppress the futile compulsion to know how everything works (which I would suggest drives all philosophical strains). We possess enough talent to smash, but nowhere near enough to construct or repair those things we smash. Perhaps, though, we possess enough talent to admire the whole that self-assembles from the parts—seemingly by magic.

Maybe the approach I have taken here is not for everybody, but I hope it helps some, as it has me.

An Appeal to Ditch Dualism

If you are not yet sold on a materialist perspective—still more comfortable believing that Life can’t be accounted by matter and physics—I ask that you try wearing it for a spell. I mean really, genuinely try it on for some days or weeks—even if you have to pretend for a bit. Starting small, see if you can make an honest effort to reconcile any experience with a physical basis—even if not smart enough to work it out in detail (a guarantee for all of us). That’s not the important part. The important part is whether you can see clear to the real possibility that the universe might make it possible, even if it eludes our cognitive capacity to fully track. The experience involves a bit of letting go: living in mystery. What would it mean if atoms in interaction really could generate what you witness? Can you get to a place where it’s even a little bit amazing? Can you turn incredulity into incredible awe? Don’t give up straight away, and you might find the Necker Cube flip—if just for an instant. One flip might be all it takes to indicate that it’s possible to admire the moxie of the universe for turning out all this amazingness using the bare-bones tools at hand—just as snowflakes turn out magnificently varied and gorgeous designs (impressively symmetric) all based on a single asymmetric, grabby molecule and a few rules of interaction.

This concludes the series as originally conceived, but I’ll take the opportunity to append a bonus post on the closely-related matter of determinism, which invites all sorts of misunderstanding and misapplication that may present yet another barrier to being comfortable with materialist monism.

Views: 1302

Your observation that (theoretically) explaining Life cannot rob it of its splendour really hits the proverbial nail on its head. Indeed, having just caught a whiff of the polar lights yesterday, I can confidently say that knowing it was caused by ionized particles interacting with the magnetosphere did absolutely nothing to temper my enjoyment of the display. Only conjurors' tricks are rendered banal by understanding. [Perhaps not even those!]

This is a relevant article about what consciousness is, from the latest issue of Scientific American, which includes related articles. It doesn't seem to be behind a paywall.

https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/what-is-consciousness-science-faces-its-hardest-problem-yet/

Interesting article, but following the NDE link revealed this depressing sentence:"Borjigin had seen the same upwelling of activity in previous studies of the brains of healthy rats during induced cardiac arrest."

Our fellow travellers didn't evolve to be tortured to death by bloodless, white-coated psychos. If these 'researchers' think such cruel experiments will give them any insights into consciousness, then they are lightyears away from understanding it.

"Maybe the approach I have taken here is not for everybody, but I hope it helps some, as it has me."

It certainly has helped me in crystalizing concerns I have had about modernity for most of my life. Thank you.

Also great image of my home town at the top of your essay

The very *nature* of our "sensors" for interacting with the world around us (yes, I know I'm on the dualistic side when I say this 🙂 )

is deeply reductionist, adaptive, and focused on the macroworld. What would it mean to see light as a stream of tiny photons, clearly distinguishing the impact of each on the special photon receptors that allow this? What would it mean if touch receptors were so sensitive that they could feel the roughness of smooth glass or perhaps the impact of each molecule on the face during the wind, etc.?

Is there a choice not to apply reductionism? Isn't it *natural*, evolutionarily provided, and materially and energetically justified (in physical embodiment)?

Even the phrase "incredible complexity" or "mystery of complexity" may not have a tangible effect, just as for most the word "infinity" or large numbers like 9^9^9 do not provide the context embedded in them and are not able to push the real awareness hidden behind these terms/meanings.

Perhaps "we do not know", as you suggested, would be better, but it does not descend to reality and does not ground in awareness, but requires practice and training in a sense of humility and letting go.

When I imagine unimistic unity, I turn to clay. Imagine everything made of ivory-colored clay, with fussy fuzzy contours and edges, connected to everything around, when you take a step, you only pull one piece from another, even the air is barely transparent from the cream dust.

Thank you!

Great way to frame the practical necessity of reductionism: unable to directly perceive the grainy distractions.

In the second part of the comment I mean the gap between reality/understanding/word, both between individuals and between parts of "complexity". Since, as far as I understand, there is no measure of complexity, we can only say that *this* is more complex than *that*. For example, a human body cell than a colonial algae. But how to explain the complexity of some processes, for example, the perception of an image to transfer it to paper (drawing) by a person and the feelings that arise when elephants visit the bones of their deceased relatives? We *say* "this is incredibly complex", perhaps without even understanding/aware of the difference, not being able to track it, etc. Or we think or say "we don't know", but I think very few people actually refrain from fantasies generated by "meat in the head"…

One condition that, I believe, every person on the planet would agree with is that more life is better than less. (Johnny Rocco: "Yeah. That's it. More. That's right! I want more!") To be alive is better than being dead. (With the possible exception of people living with incurable excruciating diseases…though I'd bet that if you could give them relief along with more life, they would choose that.)

Ernest Becker explores this in his book "The Denial of Death." One conclusion he comes to is that every person, early in life, develops a "theory" about why s/he should have more life than, say, a pig (that, with appropriate processing, is the source of tasty stuff like bacon). The principle structure, says Becker, that people rely on as a framework for why they should have more life is culture. My culture (us) is better that your culture (them), so killing you is justified if it means that I get more (even to the point that dying in order to kill you is a good thing if it "proves" that my culture is better than yours).

If you say that my culture (based on materialism) is better than yours (idealism), you are not simply exploring the nature of reality, you are challenging the basic assumptions of the idealist about why they should have more. You are suggesting that the "understanding" they have about why they should have more is false. They don't deserve more, any more than you do. Suggesting this to someone with a deep commitment to the idealist position could very well get you killed.

The current state of the planet is challenging the assumptions of nearly everyone regarding who gets to have more (That's right. I want more!).

I don't agree that more life is better than less. I don't agree with the reverse, either. "Better" is highly subjective, so I'd just go with "it is what it is." Also, I've never been dead so I don't have an opinion on whether it's better than being alive but I strongly suspect I wouldn't care about the question at all, if I didn't exist (sometimes referred to as being dead).

Thank you Tom for generously sharing your ideas and words on this matter (pun intended)…

I personally still find it hard to ditch the idea/possibility of dual-aspect monism, which I don’t see as necessarily being just a shadow form of Cartesian dualism. Formulations of it by Bohm, Pauli, Wheeler and others invoke the notion of a deeper, undivided level of reality (ontologic reality?), with the “mental” and “physical” being different aspects of this true reality (epistemic aspects?). So the underlying “substance” of reality is actually a single one, with the mental and physical being different “manifestations” of it (or ways of knowing it?). The physical and mental both derive from this single underlying “substance”, not one from the other.

I myself would replace the term “mental” with the animist’s “Spirit” (equating to self-awareness in combination with a “will to move”).

But one can argue that this is all just words and a “clever” mental trick to keep the mental on par with the physical, so “shadow dualism”. I can’t eliminate that possibility.

Thanks Tom!

Tom : I still firmly believe you should go on a mainstream podcast, such as any on this top 20 list :

https://podcastcharts.byspotify.com/

The fact that you even have this blog must mean that you want to share your message, right? Why not share it where it may be heard by more people?

I believe your message will not be liked by many people – but what matters more is that you are actually correct about probably a lot of the things involving our energy and resource consumption and limits to growth and modernity.

Thank you sir for sharing the knowledge you have gained!