The day you met your spouse, it was love at first sight. They were charming, witty, warm and affectionate, good-looking, complimentary, showered you with gifts, devoted time to you, pledged to look after you into your old age and even to help take care of your aging parents. They impressed you with their big dreams: raising a family, buying a big house, owning expensive cars, traveling the world, and they were inexplicably adept at putting meat on the table.

The day you met your spouse, it was love at first sight. They were charming, witty, warm and affectionate, good-looking, complimentary, showered you with gifts, devoted time to you, pledged to look after you into your old age and even to help take care of your aging parents. They impressed you with their big dreams: raising a family, buying a big house, owning expensive cars, traveling the world, and they were inexplicably adept at putting meat on the table.

It goes without saying that you got married. What a lucky catch!

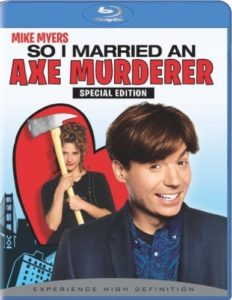

It didn’t take long before suspicions arose: unaccountable nocturnal absences; waking to the sound of laundry being done at 4 AM; an odd reluctance to move the axe out of the car trunk and into the garage with the other tools. But why spoil a good thing with awkward questions? Life for you is going great, so better not to rock the boat with silly notions of some monstrous secret. Plus, you’re in love!

But the cops finally caught up and your yard turned into a media-infested nightmare. It took ages to even accept the possibility that this was real—not a case of mistaken identity or wrongful framing. How could such a generous and loving partner really be a violent menace?

So here’s the thing: Modernity is an axe murderer, and we’re—unfortunately—married to it. It isn’t hard to see modernity’s fatal flaw of being constitutionally unsustainable, and that it’s on a violent rampage. Turns out it’s been out at nights murdering the planet.

So how do we react? What does this mean for us?

Most people make the mistake of being so enmeshed (co-dependent?) in modernity that they lose themselves within it and come to believe that they themselves are modernity—and that humanity in general is modernity. By this logic, a failure of modernity is a failure of humanity, which is grievously unacceptable. If modernity is an axe murderer, and has finally been caught out (by an ecosphere that can’t take any more), then life would seem to be over. Despair sets in. Denial, anger, and bargaining might also compete for attention, but acceptance seems tantamount to suicide: total capitulation; complete failure.

This is an unfortunate tendency. We are not modernity. Humans are not modernity. If modernity fails—as it must—then so be it. We’ll do something different. The spouse of an axe murderer need not themselves be locked away on death row, but more constructively can get a divorce, heal emotionally, and move on. The transition will be painful, confusing, involve heaps of uncertainty, and unavoidable ugliness. But something awaits on the other side that could well be better. In fact, if it doesn’t have failure and ecocide built into its foundation, isn’t it automatically better?

If this sounds like magical thinking: that we could just wake up sporting a post-modernity attitude and suddenly be free of its burdens, then I apologize. Nothing about the transition will be easy, or fast. Most individuals alive today are unlikely to navigate such a momentous mental shift, so that the transition will largely come about through generational turnover. Those born into a transforming world will have less trouble accepting key new realities they find themselves operating within. Despite my best hopes, I have to admit that the transition probably won’t be ushered in on a wave of awareness and proactive changes, but rather will involve a reluctant, protracted retreat as continuation simply becomes untenable. Some will adapt better than others, taking it all in stride.

But maybe a number of us can help the transition by recognizing what elements can persist long-term and what cannot; what attitudes are helpful vs. harmful; and what our relationship to the more-than-human world would need to be for long-term happiness and thriving of humans as part of a larger community of life. We can help “midwife” the transition and get people through the turbulence—most simply by remaining calm and thoughtful as big changes unfold.

Also, having more people be aware of the inevitable failure of modernity will allow a more graceful sloughing-off of its trappings so that we’re less clingy and not helping to propagate modes that just don’t make sense anymore. It has to start somewhere.

I can appreciate that my assertions of modernity’s necessary demise may strike many readers as unjustified and overly-dramatic. This topic deserves a post (or more) of its own, which I am preparing. But in brief, unsustainable things fail—by definition. Any growth-based system fails on a finite planet. Any system reliant on non-renewable resources (fossil fuels, mined materials, drained aquifers) fails. Any system that drives ecological collapse fails. Any system whose population, scale, and complexity is based on a temporary resource (ahem…fossil fuels) fails. A look at the cliff edge plot might suggest shifting the label of “overly-dramatic” away from me and onto modernity’s destructive capacity. I’m not the one producing the dramatic assault on Earth’s vitality.

A Comment on Comparisons

Getting people to recognize the atrocities of modernity (seeing beyond the numerous and obvious personal benefits) is most effective when comparing its many negatives to atrocities against humans. We don’t tend to register other kinds of atrocities as reliably. In the foregoing metaphor, it goes without saying that the axe murderer is targeting human beings. This fact seems to be what makes the murderous behavior abhorrent In fact, we typically restrict the word “murder” to the killing of humans for some reason. At a larger scale, when speaking of the obliteration of the natural world, we might relate it to a holocaust (again, typically applied only to humans), which we universally recognize as a bad thing. To me, this speaks to our human-supremacist cultural tendencies: we view human lives to be “sacred” in ways that we fail to apply to the more-than-human world. Think about the question: is it possible to murder a plant or animal? Does the context matter? Might we categorize killing for subsistence differently than for extermination, elimination, eradication (e.g., pest control)? What if the same result is a matter of negligence? Can we still go to jail for the unwitting slaughter of the natural world?

In any case, pointing out that our culture is rooted in human supremacy—even if lacking a hateful basis—conjures connections to white supremacy, male supremacy, and quickly leads to thoughts of a Nazi regime as an apt analogy: domination by a self-declared master species. Will future generations look upon modernity as similarly monstrous in its elevation of humans above other life? God, I hope so.

I’m sure that just like our axe murderer, Nazi Germany provided many welcome perks to most of its citizenry—more easily appreciated if not aware of or receptive to the tremendous cost to others. Likewise, modernity provides many short-term perks to many humans, but the entire community of life is suffering greatly in the bargain, now gasping for breath.

Anyway, it’s a bit of a sad confirmation of our culture’s human supremacist leanings that analogizing to an atrocity against human beings seems like the only sure-fire way to make the point that something is bad.

Next Time Around

I’ll say this: after the ordeal with the axe-murderer is over, you’ll ask better questions on future first dates! In the post-modernity case, those questions might be:

- Do you elevate humans above the rest of nature, or put the entire community of life first?

- Are you more attracted to hubris or to humility?

- Do you promote growth, or place more value on long-term sustainability?

- What are your control issues? Do you seek ultimate mastery or do you humbly accept limits?

- Do you support legal ownership of land (and its life and resources), or see Earth as a gift to the entire community of life, to be shared?

Any affirmation of the first halves should constitute instant disqualification. No more monsters!

Views: 2642