Kids these days. When I was a lad, tantrums were redressed with a spanking. Heck, spankings (at school) were answered by further spanking (at home). In polite company, we might apply the euphemism “attitude adjustment” to mask the unpleasant image of a bawling kid bent over the knee getting red in the tail. I’m not going to wade into the issue of whether or not such treatment is the most effective way to shape responsible adults, but I will say that I think our society needs some sort of attitude adjustment when it comes to expectations of our future. I’ll take a pause from the renewable energy juggernaut recently featured on Do the Math and offer some seasonal scolding. Think of it as my “airing of grievances” component of Festivus: “a holiday for the rest-of-us,” as introduced on Seinfeld.

People Want Stuff

Over the years, my diligent observation of people has led me to a deep insight: people want stuff. I know—bear with me as I support my argument. Donald Trump. Okay, I think I’ve covered it. No, it’s true. On the whole, we don’t seem to be satiable creatures. Imagine the counter-examples: “No thanks, boss. I really don’t need a raise.” “I’m done with this money—anybody want it?” “Where should I invest my money to guarantee 0% return?” (Answer: anywhere, lately.) I’m not saying that the world lacks generosity/charity. But how many examples do we have of someone making $500,000/yr (in whatever form) and donating $400,000 per year to those in need, figuring $100,000/yr is plenty to live comfortably? I want names (and actually hope there are some examples).

This basic desire for more has meshed beautifully with a growth-based economic model and a planet offering up its stored resources. The last few hundred years is when things really broke lose. And it’s not because we suddenly got smarter. Sure, we have a knack for accumulating knowledge, and there is a corresponding ratchet effect as we lock in new understanding. But we have the same biological brains that we did 10,000 years ago—so we haven’t increased our mental horsepower. What happened is that our accumulation of knowledge allowed us to recognize the value of fossil fuels. Since then, we have been on a tear to develop as quickly as we might. It’s working: the average American is responsible for 10 kW of continuous power production, which is somewhat like having 100 energy slaves (humans being 100 W machines). We’re satisfying our innate need for more and more—and the availability of cheap, abundant, self-storing, energy-dense sources of energy have made it all possible.

As we stand on the precipice of a transition away from this magic elixir, we are still heady with our sense of progress. We feel the wind in our hair and we know with certainty that the present would have been unimaginably rich and complex to someone living 200 years ago. Humans—and especially homo economicus—are ruthless extrapolators, and “know” with the same apparent certainty that the future will be as mind-bogglingly rich and complex and incomprehensible to us simpletons alive today. I get it. I admire the sentiment that we would be foolish to think we know where the far future leads. But as I’ve already pointed out, the same humility can be applied in the opposite direction: “Who, in the year 2011, at the height of the fossil fuel binge, could have possibly imagined that here we would sit in 2211, huddled around a fire, sharing stories—ever less believable—of the days when we could walk on the Moon? Hey, you gonna eat that last grasshopper?”

How many people are offended, scandalized, or just plain irritated by my suggestion that the future may be a step backward from where we are today? If you’re one of these, then you’re a candidate for an attitude adjustment. Don’t you give me that look!

The Case for Reversal

Bear in mind that I am no more qualified than any living person to know what the future will bring. Be very wary of anyone who expresses confidence about where we will be in 200, 100, or even 50 years from now. In truth, the future could be unrecognizably harder than today in as little as 20 years. To reject this real possibility is to be willfully biased toward a bright future. Just because I warn of a possible future of hardship does not mean that I reject the notion that we could pull through the transition ahead in glorious fashion to a splendid shiny future for all. In fact, I’d love to see this happen, and I’d love it if we find a way around all my worries. But given the scale of our challenges, we would be foolish to assume that this path will materialize.

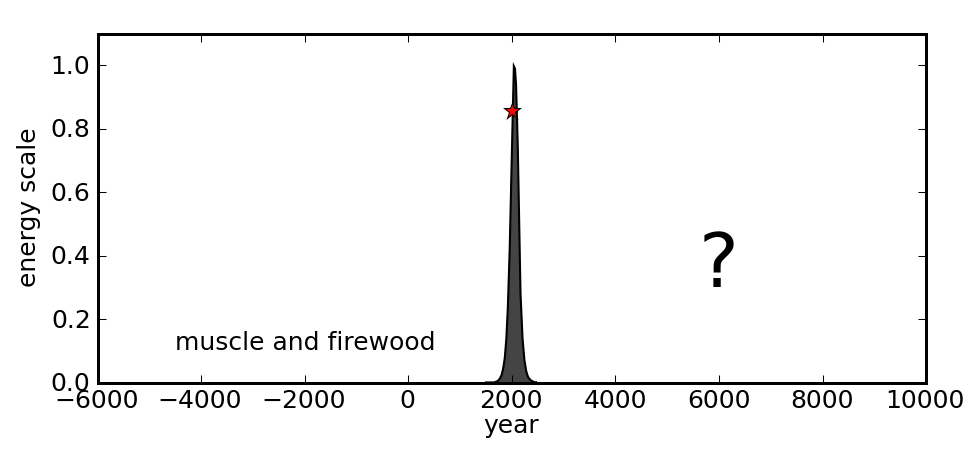

For me, the most compelling way to put the present era in perspective is to look at a cartoon plot of fossil fuel availability over the long term (as in the sustainable post).

This plot snaps us out of the short-sightedness of our own lifetime (that things are always growing/improving as we have always known them to be), and highlights the utterly special nature of the here and now. We learned from the Copernican Revolution that we should adopt humility in assessing our place in the cosmos: we are not at the center of things the way we tend to think. Perhaps we have taken this lesson too much to heart, because it makes it harder for us to appreciate that we actually are near the center of the fossil fuel curve. Assuming that a high-tech future will naturally unfold on the back-side of this curve is dangerous. If you’re stuck in this mindset, I’ll give your backside something to think about…

On a related note, the fossil fuel boom has brought with it a population boom, unprecedented resource exploitation, global warming, etc. Yes, humankind has always faced challenges. And we—arguably—have a good track record for coping with them (if we exclude the moronic Romans, Mayans, Easter Islanders, etc. from our club). Many are tempted to extrapolate past successes into a postulate: that we will always innovate our way out of problems. The only thing that remains mysterious is just how we will manage. But for us to pretend that we are not stressing the ecosystem on a multitude of fronts at a scale never before seen in this world is irresponsible. It really is no wonder that we have a sense of unraveling. The future is unwritten, and the recent past may not be a good template for the near future. We must accept that we face in the decline of fossil fuels the mother of all problems for humanity, and that past success has been against the backdrop of cheap and abundant energy. An unfamiliar phase awaits.

See the Do the Math post on peak oil for particulars on one scenario that has me worried. In brief, a declining petroleum output leads to supply disruptions in many commodities, price spikes, decline of travel/tourism industries, international withholding of oil supplies, possibly resource wars, instability, uncertainty, a sea change in attitudes and hope for the future, loss of confidence in investment and growth in a contracting world, rampant unemployment, electric cars and other renewable dreams out of reach and silly-sounding when keeping ourselves fed is more pressing, an Energy Trap preventing us from large scale meaningful infrastructure replacement, etc. There can be positive developments as well—especially in demand and in “attitude adjustments.” And perhaps the market offers more magic than my skeptical mind allows. But any way you slice it, our transition away from fossil fuels will bring myriad challenges that will require more forethought, cooperation, and maturity than I tend to see in headlines today.

Reactions

People often misinterpret my message that “we risk collapse,” believing me to say instead that “we’re going to collapse.” It’s interesting to me that the concept of collapse is taboo to the point of coming across as an offensive slap in the face. It clearly touches an emotional nerve. I think we should try to understand that. Personally, this reaction scares me. It suggests an irrational faith that we cannot collapse. If I did not think the possibility for collapse was real, I might just find this reaction intellectually intriguing. But when the elements for collapse are in place (unprecedented stresses, energy challenges, resource limitations, possible overshoot of carrying capacity), the aversion to this possible fate leaves me wondering how we can mitigate a problem we cannot even look in the eye.

Others react by an over-use of the word “just.” We just need to get fusion working. We’ll just paint Arizona with solar panels. We’ll just switch to electric cars. We just need to go full-on nuclear, preferably with thorium reactors. We just need to exploit the oil shales in the Rocky Mountain states. We just need to get the environmentalists off our backs so we can drill, baby, drill. This is the technofix approach. I am trying to chip away at this on Do the Math: the numbers often don’t pan out, or the challenges are much bigger than people appreciate. I have looked for solutions to things we can just do to alleviate the pressures on the system. With the exception of just reducing how much we personally demand, I have been disappointed again and again. I’ll come back to personal reduction in the months to come: lots to say here.

Another common reaction (that I have had myself) is to get excited about a technology that is not yet demonstrated, but seems awfully promising. Some refer to the effect as “hopium,” and yes, it is addictive. What I have found in myself is that the less I know about something, the more prone I am to the “hopium” effect. This is another part of human nature. I have noticed in my professional life that when multiple people are involved in the diagnosis of a complex problem involving many interacting components/subsystems to which each member has contributed some piece, there is a tendency for each person to cast suspicion on the component they understand the least. Conversely, when looking for a solution, we give a pass to the concepts with fewer known, demonstrated hangups.

It may well be that our energy/resource salvation lies in some presently obscure or unappreciated technique. But realizing that obsession with these notions means bypassing tried-and-true “conventional” technologies like solar photovoltaics, solar thermal, wind, hydroelectric, geothermal, conventional fission, lead-acid storage, etc. to me is a tacit acknowledgment that the main ideas we have on the table are not obviously going to cut it. Such enthusiasm for the unproven—often accompanied by statements of unmitigated hope (“our best hope,” “the only real solution,” “we must aggressively develop,” etc.)—carries with it a ring of desperation. It’s maybe like a dog whistle: I’m not sure all of us hear it. The trick is to remain attentive to the real potential underneath the shrill sound of fantastical thinking, in case salvation actually does lie within.

Addiction to Growth

I kicked off the Do the Math blog with a two-part argument that growth is fated to end. A surprisingly common reaction to the irrefutable physics telling us that growth on Earth must cease was the exuberant assertion that we would just move our growth show to space and to other planets. I was (temporarily) at a loss for words. I later addressed this attitude in a post on the hardships of space, but was still dumbfounded by the cult-like tenacity of the space-faithful. How did we create this phenomenon? Again, I’m not opposed to the notion that space futures may be possible someday, but how will we confront our near-term challenges in a rational way when many see space as the solution?

Aside from the cadets, the message was clear from reactions that growth is a sacred underpinning of our modern life, and that we must not speak of terminating this regime. After all, how could we satisfy our yearning for more without the carrot of growth dangling in front of us? Some argue that we need growth in the developing world in order to bring humanity up to an acceptable standard of living. I am sympathetic to this aim. So let’s voluntarily drop growth in the developed countries of the world and let the underdogs have their day. Did I just blaspheme again? I keep doing that. I perceive this compassion for the poor of the world as a cloak used to justify the base desire of getting more stuff for ourselves. Prove it to yourself by asking people if they would be willing to give up growth in (or even contract) our economy while the third world continues growing for the next half-century. You may get rationalizations of the flavor that without growth in the first world, the engine for growth in the third world would be starved and falter: they need our consumer demand to have a customer base. I’m skeptical. I think people just want stuff—even if they’ve got lots already.

So I don’t know how this impasse gets resolved. Growth must one day cease, but human nature seems to be stacked in opposition to this prospect. Maybe it means we’re incapable of establishing a steady state, and are instead fated to boom/bust cycles on a global scale. And that doesn’t taste very nice, does it, precious?

A colleague pointed me to a well-thought article in The Nation by Naomi Klein making the case that climate change poses a legitimate threat to capitalism, so it’s no wonder that we find opposition to the science on ideological grounds. But the point is valid whether talking about climate change, peak oil, resource limitations in general, or the very notion that there are limits to growth. All challenge the prevailing economic scheme, and therefore threaten sacred ideologies. Capitalism and democracy are a match made in heaven—together maximizing the potential for growth. But physics puts us on a collision course. Democracy in particular will have trouble coping with limits, because to the extent that the right answer involves scaling back, an adult politician (I know—snort) proposing such austerity will be handicapped against a candidate promising a chicken in every pot.

As an aside, science has enjoyed broad public support as a foundation for technology. But as science increasingly tells us what we can’t expect to do in a world of diminished resources and compromised environment—rather than only opening up new possibilities—we’ll see how popular science remains. The ideological lines are already forming.

Where are the Adults?

We’ve all seen kids present parents with irrational demands. It could be a pony, a jet pack, a real light saber, a trip to the Moon, or a swimming pool on the roof of the (single-story) house. Adults are adept at deflecting these requests—sometimes with logic, and sometimes with distraction tactics. Adults know that some of the demands are technically impossible, or that others are simply outside their financial means. Just because we want something doesn’t mean it is possible to have it. Just because we want our fossil fuel alternatives to be as cheap and convenient doesn’t mean they will be, no matter how much we might belly-ache.

Somehow, kids who vow to eat only ice cream as adults or look forward to never having to go to bed learn for themselves as young adults that these are not viable strategies—no matter how desirable they seemed to be as a kid. Likewise, kids grow out of fantasies like believing in Santa Claus, the Easter Bunny, and the Tooth Fairy. Yet, just as we don’t shake all of our mythical beliefs as adults, we don’t shed all of our irrational expectations and demands for the future.

When we are told we can’t keep growth going, that we face resource limitations, or that alternative energy sources may not be able to maintain our current standard of living, we see tantrums. When we’re told we can’t have free checking anymore, we howl in protest. When fuel prices skyrocket, airlines dare not raise airfare enough to cover costs, or the fits we throw will cause significant loss—so they lose money with under-priced fares and hope to make it up by keeping prices a bit elevated after fuel prices begin to ease. When taxes go up or stamps cost more, what do we do? We kick and pound the floor. Granted, some injustices are addressed effectively by tantrums, and sometimes with stunning results (Boston Tea Party). But on the whole, our tantrums are not held in check by the equivalent of a parent. We’re free to howl.

Many look to political leaders for, well, leadership. But I’ve come to appreciate that political leaders are actually politicians (another razor-sharp observation), and politicians need votes to occupy their seats. Politicians are therefore cowardly sycophants responding to the whims of the electorate. In other words, they are a reflection of our wants and demands. A child who has just been spanked for throwing a tantrum would probably not re-elect their parent if allowed the choice. We all scream for ice cream. Why would we reward a politician for leading us instead to a plate of vegetables—even if that’s what we really need. Meanwhile we find it all too easy to blame our ills on the politicians. It’s a lot more palatable than blaming ourselves for our own selfish demands that politicians simply try to satisfy.

My basic point in all this is that I perceive fundamental human weaknesses that circumvent our making rational, smart, adult decisions about our future. Our expectations tend to be outsized with respect to the physical limitations at hand. We quickly dash up against ideological articles of faith, so that many are unable to acknowledge that there is an energy/resource problem at all. The Spock in me wants to raise an eyebrow and say “fascinating.” The human in me is distressed by the implications to our collective rationality. The adult in me wants less whining, fewer temper tantrums, realistic expectations, a willingness to sacrifice where needed, the maturity to talk of the possibility of collapse and the need to step off the growth train, and adoption of a selfless attitude that we owe future generations a livable world where we can live rich and fulfilling lives with another click of the ratchet. Otherwise we deserve a spanking—sorry—attitude adjustment. And nature is happy to oblige.

Okay: “Airing of grievances” complete. Now for the “feats of strength.”

Views: 8985

Interesting post. However, as far as I have seen you have not actually demonstrated in your postings so far why all out nuclear based in fission reactors would not be feasible in the same way as fossil fuels based systems are. I understand that there is a strong emotional resistance to this, but that is different from saying that it cannot be done. When I look at the numbers, it looks clearly doable and main problems have to do with politics.

I will ultimately tackle the nuclear side of things. In short, yes, the numbers are supportive (under breeder programs). But there are a variety of practical challenges even outside the political/fear issues. I believe nuclear will play an increasing role, but I also don’t hold it up as any form of salvation.

Nuclear is probably a part of what we are going to do. But it is trivially obvious, and earlier posts made it abundantly clear, that no energy technology, even zero-point perpetual-motion voodoo, will allow growth to continue. Growth must stop.

Growth must (and will) stop, yes, but we’ve got many, many generations before growth itself is our biggest problem. Our problem right now isn’t growth per se but exhaustion of our current favorite resources and our inability to clean up after ourselves. But there’s still more than ample room for growth, and it would be foolish to reflexively assume it would be a bad idea to grow ourselves out of our current problems.

Have one of Tom’s magic ice-cream-eating ponies build a seaborne raft the size of Texas covered in photovoltaics with superconducting connections to all the world’s electric grids, and have it also power a plant to suck CO2 out of the air and turn it into petroleum products, and we can merrily continue on our existing growth curve for several generations before we’d have to worry about anything.

Had the industrial revolution been fueled from the beginning by photovoltaics rather than petroleum, that’s exactly where we’d be right now (though, of course with much more distributed production). We’d have grown even faster and bigger than we did and we wouldn’t be facing the problems we do today. (Of course, that’s a fantasy; energy storage as good as petroleum is a hard problem, a key component to our industrialized society, and still not practical today outside the lab.)

It may well be that the best way forward is a solar-fueled growth spurt, and to not attempt to slow and stop growth until (long?) after we’ve fully outgrown petroleum. I don’t know, and neither do you…but I think Tom might have a crystal ball which could give us some answers.

Cheers,

b&

How many, many generations? There have only been 70 generations of 70 years, end-to-end, since written history began five thousand years ago.

It’s more like 200 generations. A generation is your birth to the birth of your children. Currently around 30 years, but shorter in the past. (I used 25yrs to get 200 generations.) 70 years is a lifespan, and is also much longer than they used to be.

I am not afraid of (overall) growth to stop. But I am afraid that if it does stop things will become unstable and we will collapse as many civilizations before us. The only difference now is that it wont be contained to some remote island (i.e., Easter Islands) or jungle (i.e., Mayas) or city state (i.e., Mesopotamia). It will most likely be global but it will not be the end of the world. It will be painful but the human brain is very much able to adapt to hardships very quickly (after the fact). Apparently people who are left paralyzed after an accident report very similar happiness scores as people who won big sums in the lottery just one year after the event (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/690806).

This suggests that we as human beings are very much able to adjust our expectations but only if we are really forced to do so.

There’s nothing wrong with wanting more wealth per person, the real problem is wanting more little people who look just like you. Children are the ultimate wealth, and the best bit is you don’t have to ask anyone for one, you just make one yourself.

But imagine an economy that grew by 0.1% (not “1%”) per year, and was 0.2% more efficient each year in terms of impact on the environment. That people lived about 83 years, dying at the rate of 1.2% per year, and had one child each, shared with one other parent (born, in the steady state, at 0.6% per year).

Then the average person in a lifetime would benefit from 0.5% more share of the environment every year, and 0.7% more wealth, while the population fell at a modest 0.6% per year, and the environmental impact on the Earth fell at 0.1% per year. As young people would start with the least wealth, the actual annual income rises experienced by one person could be several percent per year (the 0.7% p.a. would only be the rise in the population average, the individual life trajectory could be much steeper). That’s not a bad life to live.

If you allow that people should not want more children than one, then you don’t have to worry where the ever-increasing wealth per person is coming from. If you don’t, then no amount of wealth is going to be enough to make all the new people better off.

Efficiency gains can’t continue forever, as you will always need *some* amount of energy to do stuff – making this argument invalid, unless I’m missing something here. Perpetual growth isn’t possible at *any* rate, 1%, 0.1% or 0.0001%, due to the nature of the exponential function. At lower rates it simply becomes ruinous less quickly. This argument smells like common-or-garden economics voodoo to me.

Does it bother you that the economy in this model is growing 0.2% faster than the environmental impact? Easily fixed. If we set that to zero, the economy is now shrinking at 0.1% per annum, while the share of the economy per person falls from 0.7% p.a. to 0.5% p.a. Still not a bad life.

And, as tmurphy points out, we’re close to crisis here; there’s value in just slowing down the growth in resource use. Even if it just puts off the crisis for another two hundred years, and makes the impact softer, that’s still a good thing.

It’s like complaining that hitting the brakes will not stop the impact with the wall– don’t you think there’s value in a) buying more time to react to the crash, and b) making the crash a bump?

[edited: Some folks] need a utopia guaranteed to last forever. I’m just looking for a way to muddle through and give the future people some options.

I had expected the objection to be that 0.6% annual decline in population eventually makes humanity extinct. That’s another problem I expect people in the future to be grown up enough to handle (“Gee, we could use more people, let’s allow two or three children per family!”) People are not going to go extinct because I passed a law, they’ll just repeal my law, which is fine.

Even if the population stabilizes, exponential consumption growth will eventually outweigh the gain of population stabilization.

That’s why I favor an exponential population decline, instead of mere stability. At -0.6% per annum, starting from 7.3 billion in 2015, it takes until 2130 to get down to 1970 levels. That was a time when population growth rate was higher than it was before or has been since, which implies it was a historically favorable time to benefit from the environment/people ratio. And there’s no reason to suppose technology will dial back down with population, so we won’t be stuck with 1970s technology or wealth per person next time around.

The bad news is, negative population growth is not as easy as I make it sound. China had one-child laws in place for decades and never managed to get its population growth rate below +1.0% per annum: that is, it never went negative at all. Only six Eastern European countries and Zimbabwe have population declines over 0.5% p.a. today, and only in Estonia, Latvia, and Ukraine is this due to birth rate rather than disease or emigration. And these populations are declining because of the necessity of poverty, which is the opposite of what we want. Japan, a rare example of a prosperous country with a declining population, is going down by less than 0.2% p.a. This means either a growing human impact per capita, or a small-to-zero growth in consumption per capita.

New little humans, much though we like them, are the ultimate emission, much more significant than carbon, and are either a cause of carbon emissions themselves, or must stay poor forever. Neither of those options is a palatable one.

I think that the human instinct to propagate is (still?) the biggest problem facing us, and still like the saying “whatever your cause, without population control, it’s a lost cause” (Paul Ehrlich).

It’s hard to see us enforcing a declining population (and achieving it) while still remaining a liberal democracy. However, if we have another great depression (or worse) because of resource limits or pollution, we may not be able to maintain democracy anyway…

Sounds perfect – bought!

One minor detail concerns the “innocent” assumption of economic growth (and be it ever so moderate) together with population decline.

Have you ever wondered how we achieve this growth? Much of it (and ever more of it) is securitisation of future cash flows. Your stock, bond, real state (i.e., in your pension fund) is (at least in theory ) valued be discounting all future cash flows. If one assumes positive real growth one can justify almost any price. In other words you feel/rich today because of all the future earthlings are going to buy the products of your stock or want to live in your house. The valuation today becomes very very sensitive to growth expectations and the valuation today influences the growth expectation of tomorrow. Consumers who feel rich spend more. The Federal Reserve Bank and other (political) bodies are trying very hard to stop any of those downward adjustments of growth expectations because it is very painful.

I think you really underestimate the problem of elites here. Take a look at the better opinion polls, such as NORC’s General Social Survey. They show the public at large wants to do more on these issues. And that is without any serious leadership on the topic, not to mention indoctrination.

Also take a look at the psychology of wealth and power. The rich are indeed different: They are greedier and less pro-social in both their attitudes and their immediate reactions. Power and privilege not only corrupt, but attract the most corruptible.

Alas, big money utterly dominates public discourse in this society (and most others). The latest research from the Sunshine Foundation says 25% of all political donations come from the richest 1% of households. The share of lobbying efforts is almost surely even more concentrated than that. All the while, getting elected to Congress takes a million dollars, due to the fact that TV advertising is the main determinant of votes.

Human beings lived for millennia without economic growth being a prerequisite of all socio-economic conduct. We could do so again, and the idea might be quite popular, if it had any ability to receive a fair hearing and some proper representation.

Alas, the power structure rules this possibility out.

I thinks it’s defeatist (and hence dangerous) to leave this out of our explanations of reality.

“Power and privilege not only corrupt, but attract the most corruptible.”

Apparently sociopaths are over-represented in politics and the higher echelons of corporations. Also, in my own experience rich people are far more damning of the poor than the average person. They come from a culture of “grab it all and keep it”, almost by definition.

Yes, I think it’s one of the two fatal flaws of capitalism (the other being the structural requirement for unending growth). By setting up raw command and wildly excessive compensation as the rewards for the most “enterprising,” these organizations function as magnets for those who are both insensitive to the impacts of their own actions and insatiable in their need for status and privilege.

Personally, I think that a large part of the human population is actually satiable, and does NOT fit the description of always wanting more. These satiable types tend to become teachers, craftspeople, and other sorts of humble workers.

I also think it’s vital to remember that whatever hold insatiability does have among the non-elites, much of it is situationally induced, not truly chosen. In a society where a comfortable, stable existence is guaranteed to nobody, there is always pressure to put as much padding under one’s belt as possible. If everybody had a livable income, a job, access to doctors, and a promise of decent care in old age, I believe most people — even in America — would immediately become far less “conventional” and far more interested in humanity’s imperiled collective welfare.

Hi Michael Dawson, I would like to learn more about your statement “The rich are indeed different: They are greedier and less pro-social in both their attitudes and their immediate reactions. Power and privilege not only corrupt, but attract the most corruptible”. Can you show me the useful studies and empirical evidences? Thanks.

Hi, Tony. Here’s the press release from one recent piece. The actual report requires access through a library or other research pay-point.

http://www.psychologicalscience.org/index.php/news/releases/social-class-as-culture.html

I would also recommend looking at Sam Pizzigati’s work, particularly his book, _Greed and Good_. Fortunately, that is available online. Look especially at the survey done by _Worth_ magazine, at page 51.

http://www.greedandgood.org/NewToRead.html

Happy New Year!

Thanks!

Great essay; thanks!

I would suggest a subject for consideration: How much energy is needed for a decent middle-American middle class life, «Doing the Math» on the basis of a significantly reduced energy budget?

Much discussion is called for on what is essential for a decent enjoyable middle American/class life, of course. Trouble is, this is not a DO-THE-MATH subject.

But I think energy is the proper currency. (The idea was proposed back in the first half of the past century by Technocracy, a movement currently headquartered in the NW of the State of Washington.)

One benefit of such analysis could be that life in a constrained-energy steady-state economy need not be all that Hobbesian − nasty, brutish and short − but with technology, we should be able to do a Whale of a lot better.

I wonder if there is some national Freudian style self loathing as we all love to hate politicians, but they seem to epitomize our own conflicted desires?

So one question is what about the EU austerity measures? They do count as an attempt by politicians to do something unpopular and say no you can’t have everything.

I thought of this too. It’s ironic that they’re doing something which is not only deeply unpopular, but also terrible for their economies. If, instead of austerity, they would instead borrow more money from the ECB and use it to fund renewable energy projects, they could have the best if both worlds.

The austerity in the EU is being implemented by the banks through “technocrat” governments that have been imposed, not elected, by … the banks. Well, the bank – Goldman Sachs leads the new governments of Greece and Italy. We’ll see how “grumpy pappa-bank” plays shortly. As for renewable energy implementation in the EU, part of the new austerity is reduction in the FiTs there, which is, combined with the banking and credit freeze, absolutely killing the industry right now.

We have meticulously honed our political-economic system to extract wealth – in order to sate our quest for instant gratification – by creating fiscal and ecological debt we then pass on to the next generations. Flawed accounting and false economic metrics have obscured these inter-generational and intra-generational injustices. Yet, they challenge our very identity: our values of justice and equality, and our commitment to democracy itself.

Bring on the attitude adjustment!

I don’t think that the problem is that people want stuff. The problem is that people want more. More of everything, which includes stuff, but also include the metaphysical. Basically, people are never satisfied with life today, wanting (and, at this point, frankly, expecting) more. When this fundamental feeling of entitlement to more runs into the practical, physical limits to growth, it seems unlikely to end happily.

I hope I’m wrong, but I’m not sure that people really change that much. Do we have any demonstrable evidence that there has ever been widespread satisfaction with the status quo among and between groups of humans? I’m not aware of any, but it isn’t my area of expertise. It seems to me that we have always been in competition with each other over resources of some kind, always wanting more or better than what we currently had. Can a mass realization of reality really change this permanently? Or is it more likely that it might ignite a temporary change, destined to last only for some short period of time? I certainly hope for the former, but my gut reaction is that the latter may be more realistic for our species.

We are a species that always wants more, in love with our growth-based economy. What is the likelihood of accepting a change in the latter without first having a change in the former?

Check out the video The Ad and the Ego (1997)-and lots of other writings. There’s a strong case to be made that inherently people don’t “want more stuff”, or “want more”. The want some, but their wants are easily satisfied at low levels of consumption The point of advertising has been and is to create want. Without it, folks mostly stop buying.

Nicely done. I especially liked your statement, “It’s interesting to me that the concept of collapse is taboo to the point of coming across as an offensive slap in the face. It clearly touches an emotional nerve. I think we should try to understand that. Personally, this reaction scares me. It suggests an irrational faith that we cannot collapse.”

It feels like suggesting that things could eventually collapse makes people assume you are a conspiracy theorist, or overdramatic, etc. etc., but when you “do the math,” so to speak, it’s clear that the world has a limit, and we would do well to respect that before the results are disastrous.

Exactly! Believe me, I still find it uncomfortable to speak of collapse. It’s the math and the appreciation that the enabling resource is about to decline that’s got me worried. The physics and math don’t tell us we must collapse: there are ways out. But these only work if we can acknowledge that business as usual runs a high risk of producing collapse. Absent that urgency, look out!

Let me further embolden you to focus on the possiblity of collapse. While I was born into and embraced the ’50s cuture of boundless optimism, my own “do the math” processes had by the ’70s opened me to the possibility of collapse.

In time I observed – whether correctly, people may disagree – that our human problem-CREATING was outpacing our human problem-SOLVING; and that the RATE at which the gap was growing…was ALSO growing.

These observations, even fairly considered against that era’s cadet escapism and Julian Simon optimism, were early indicators, I thought, of the collapse of civilization. The phrase was discomforting then (and is still, as you’ve discovered) and I was not emboldened to use it publicly until years later when three smart and courageous individuals went public:

Lester Brown (Plan B: Rescuing a Planet Under Stress and Saving a Civilization in Trouble, 2006, following decades laying out metrics for the health of civilization); Jared Diamond (Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed, 2004); and Ronald Wright (A Short History of Progress, 2004).

We own them each, and now you, Tom, a great debt of gratitude for articulate analysis and great courage challenging sacred beliefs with “do the math” rationality.

Though it is happening more slowly than most humans can see – encumbered as our species is with short-term-vision and perpetual-growth-ideology filters – evidence that civilization is collapsing is increasingly apparent – to me, anyway. This observation is informed by lots of real world time and energy spent trying to tip civilization toward sustainable. But what mere human brain can really know? I agree, none of us can, not quite yet.

But even if civilization is collapsing, managing a softer landing is still persuasive. And – if my observations are all wrong – those sofer landing efforts could well make the difference in averting a collapse. Whichever turns out to be our CHOSEN history, thank you for your heroic efforts. Our fate is in our hands.

Thanks for the validation. My one guiding principle is that even though people as organisms may be predisposed to overshoot and collapse, we do have big brains that might be capable of plotting a trajectory to a “soft landing.” We should at least try. If we are wrong about the likelihood of collapse, then so what?! If we end up succeeding in putting ourselves into a sustainable existence as a consequence, then who could howl about that? The risk is asymmetric: Responding as if collapse were likely is far less costly than assuming it can’t happen and watching it crumble.

Your “so what” is right on, and is captured by this cartoon that I have at the end of some of my presentations on energy issues.

Tom, you’ve spilled many electrons detailing all the problems we face, and you’ve written on some broad-brush alternatives, but you haven’t really posted a whole lot on how we might realistically get from here to there.

In the last go-round, I expressed some optimism that, in the past decade, we’ve gone from hybrids being a curiosity to mainstream; and that plugin hybrids and pure electrics, though currently curiosities, seem poised to similarly become mainstream in another decade. And I think that would go a long ways towards leveling out the petroleum plateau.

I’d love it if you could “do the math” on some of those types of scenarios. Take a “long picture” view. How fast do we have to transition our vehicular fleet away from petroleum to avoid significant hardship? Can it be done in a way that lets us keep airliners in the sky, all the way to the point that we’re using PV to suck CO2 out of the air and turn it into jet fuel? Of course, the faster we transition, the longer our remaining reserves will last…and that kind of recursive analysis is way above my pay grade.

I’d also appreciate if you could work some basic economics into the mix, since I think that’ll be the best predictor of what we’ll actually wind up doing. After all, if solar cost half as much as coal, nobody would ever dig another coal mine. Can you project out some price curves as petrochemicals get more scarce and (hopefully) alternatives continue to get dramatically cheaper? And, again, include how price will influence extraction rate and therefore remaining reserves and time to depletion?

As it is, I don’t think anybody who frequents this site really has much of a clue how much (or even if) we should worry. We’re all guessing and handwaving. But I think you could perform a realistic analysis of the big picture, just as you’ve done for so many of the individual pieces, that would give us an excellent idea of just what kind of future is most likely.

Cheers,

b&

“So let’s voluntarily drop growth in the developed countries of the world and let the underdogs have their day.”

*Energy* growth per person has already voluntarily dropped, at least in the US. Was this not already addressed adequately in the comments on the Growth article by Jim Glass?

https://dothemath.ucsd.edu/2011/07/can-economic-growth-last/#comment-167

As Glass points out, from 1973 to 2009 energy consumption per person in the US dropped an average of 0.4% per year, while during the same period GDP per person increased 2% per year. I’ll add that since 2000 the drop in US energy US per capita has accelerated, to over 1.5% per year. If the point is curiously instead about an objection to economic growth as detached from energy then I have missed it.

Have you accounted for the exported industry (e.g., China) that supports our standard of living? We “hide” a lot of our energy dependencies overseas.

Good question. I don’t know how to address it other than to get some idea of the embodied energy in both US imports and exports.

The top categories of US exports by dollar value appear to be transportation equipment, computers/electronics, chemicals, machinery, petrol and coal *products*, misc. manufactures, agriculture [1]. Aside from smart phones, I suspect those those categories are high on energy intensity. Then there is the issue of trade imbalance. The 2011 US trade deficit is some $600B/year [2]. About half of the trade deficit is accounted for by the ~9.1 mbbl/day of crude imports @ ~$80/bbl, the refinement and consumption of which already goes on the US energy tab, if not the foreign incurred production energy. This leaves ~$300B (2% GDP) more (say) Chinese t-shirts and Korea cars coming in than (say) Caterpillar excavators and Boeing airplanes going out. Maybe I’m wrong, but I don’t see a large *net* export of energy dependence here, relative to US domestic energy use.

[1] http://tse.export.gov/TSE/ChartDisplay.aspx

[2] http://www.census.gov/foreign-trade/balance/c0004.html

Not to mention, much of the GDP “growth” involved deficit spending (private and public), essentially pulling forward demand.

This aside from all the problems with GDP itself as a measure of progress.

I do not credit much GDP growth to deficit spending, given the federal deficit has averaged only 2-3% of GDP since 1970 until the recent deficit explosion in 2008, after which GDP growth has been negative or lousy.

http://www.usgovernmentspending.com/spending_chart_1970_2011USp_13s1li011mcn_G0f

I would not attempt to make GDP and progress an exact match either, but I gather GDP growth is close to what Tom means when referring to the end of economic growth in his articles.

Not all of the deficit is in the government.

Bill Gates gave about 90% of his wealth to his foundation. But I guess being the richest man in the world puts a different perspective on things.

“His foundation.” Keywords. That’s not charity, that’s tax evasion.

Eh, no. The foundation spends the money on things like malaria vaccines.

Malaria vaccines – delivered by mosquito, no less – which will increase population in the most poverty-stricken areas of the world. I’ve spent a lot of time in some of those areas and wonder occasionally about the long term efficacy of such programs. Gates might spend his foundation cash closer to home, perhaps in rehabbing and retrofitting the nation’s decayed rail rights of way in preparation for the collapse in liquid transportation energy availability.

At least he’s not backing – that I’m aware of – the comical “SeaSteading” constructs of people like Elon Musk (“libertarian man made islands” for rich people … if you’ve lived around Aspen or Vail, the concept is hilarious, since these folks have lawyers with nothing to do but litigate over HOA rules for decades!)

That you disagree with his charity’s goals doesn’t make it any less of a charity.

Gates talks quite a bit about overpopulation though. Fixing the problem is complex and counterintuitive. Higher rates of child mortality, for example, lead to faster population growth, because people overcompensate with even higher birth rates. On the other hand, better education, particularly of women, lower birth rate. The foundation does a lot of work on education in the third world (and also some in the U.S.).

The solution to high population growth is to make those regions more like the regions with low population growth.

Point taken, but I think the other side is that empirically, technology does advance. If you project a future without taking that into account, you’re not going to get it right.

This can be as true of nuclear power (for example) as any other technology. It hasn’t happened very quickly in the U.S. because of political and bureaucratic interference, but China is starting to make major investments in advanced fission reactors, from GenIII (safer but still inefficient in uranium usage) to fast reactors and liquid thorium reactors (much greater long-term potential, but it’ll take a decade or two before they’re ready.)

For most power sources, this series has looked at the theoretical limits of what they can achieve. If you do the same with fission, the answer will be very positive.

“Point taken, but I think the other side is that empirically, technology does advance. If you project a future without taking that into account, you’re not going to get it right.”

Dennis, it is too simplistic to say only that “technology advances”. In fact, what we are witnessing is a deceleration of the rate of advance in many areas of research. The idea of a continual, linear advancement in technology may turn out to be the same type of myth as the inevitability of continuous growth. And our perception of the value of new technologies may have to be tempered by the unprecedented environmental destruction happening now as a result.

Technology definitely isn’t linear. Some areas are hitting their limits, others are exponential (computers, dna sequencing), or at least at an early stage of an S-curve. Nuclear technology stalled for a while because of political obstacles in the U.S., but now it’s picking up, because of new investment in a variety of places, chiefly China. (And nuclear is a solution to quite a few environmental problems.)

“Where Are The Adults?”

Haven’t you heard that the U.S. is down to its last one hundred grown-ups?

http://goo.gl/WjmOX

(The Onion truly is America’s finest news source these days.)

Super funny. Indeed, these are the very adult traits I’m talking about:

Off topic, but I seriously cracked up over the headline: U.S. Finishes A ‘Strong Second’ in Iraq War.

“Growth must one day cease, but human nature seems to be stacked in opposition to this prospect.”

Tom,

You could not be more correct. It’s not just human nature that is opposed. As Richard Dawkins (http://richarddawkins.net/) would point out, it is a key characteristic of all life forms to attempt to dominate resources (ie, grow & reproduce) at the expense of less-closely related life forms. In the absence of high pre-reproductive death rates due to pathogens or predation, a boom and bust cycle based on resource fluctuation is the norm. While some of us may hope to see a more equal and less populous world, recall that a guy like Osama Bin Laden had over 20 children, while most of your readers have had one or two. So in the next generation, whose genetically determined attitudes toward sharing resources, or limiting reproduction, will get spread most effectively?

“genetically determined attitudes toward sharing resources”

No such thing exists, and whatever human nature is, not only are we are decades or more away from understanding it, but one thing we already know about it is that it is deeply and radically affected by the eco-social conditions in which it operates. Go back and read your Einstein. Human nature is compatible with a large number of eco-social arrangements. What matters is how we configure those arrangements to channel our urges and choices and habits.

If “human nature” is so inherently and clearly greedy, why did our species spend it first 40,000+ years out living in super-egalitarian bands? Why don’t you charge your children money for their suppers?

Inverted Social Darwinism will get us nowhere.

“Why don’t you charge your children money for their suppers?”

Let’s explain this with basic evolutionary principles. People (and all living things) seek to advantage their children (and even other adults in their “super-egalitarian tribe”) because they are closely related and therefore are more likely to bear the same genes. Conversely, they have are evolutionarily biased against sharing resources with those of unrelated heritage. So, for example, no human consensus has arisen to share the Great Plains so buffalo can have their grazing grounds back, even though we all understand that what we did to the buffalo was not fair.

Mathematicians and physicists write blogs like this to explain that answers to energy depletion cannot violate the laws of thermodynamics. However, fewer of these highly trained minds are also equally conversant in the biological sciences. Deciding that we can solve our problems by somehow teaching 7 billion people how to share is just as naive as thinking we can drill our way out of our oil dependence, or that cold fission is going to arrive just as coal and oil run out. No solution will work that violates ANY of the sciences. Tom’s article shows that he gets this:

“Growth must one day cease, but human nature seems to be stacked in opposition to this prospect.”

CBreeze, if your Social Darwinist just-so story about why I don’t charge my children for their spaghetti is accurate, then why don’t I charge my step-daughter for hers? Or my friends, for that matter?

Meanwhile, human nature is neither well understood nor obviously stacked against non-growth economies. In fact, our species has spent 99.9 percent of its life living in such economies. If greed is so powerful, why the long delay in its enshrinement?

Our problem is situational, not genetic. We developed class-divided societies 6,500 years ago. The elites that perpetuated them eventually learned to sail the oceans and make steel weapons. Then, they discovered fossil fuel combustion, and we off to the races.

I prefer an analogy to a drunken teenager. Will we grow up in time to save ourselves from the convergence of class domination and fuel binging? Genes have no part in the debate, other than in the fact that our genes make us human, meaning a social animal capable of learning and surviving, or sticking our heads in the sand and dying out.

How does the human propensity to naturally limit child bearing when prosperity is available factor in. The key factor appears to be education and a per capita income of $5000 or so or at least the prospect of such income.

We know of China’s one child policy but what is less well known is that just about every section of the planet including India, Arab countries, Latin America and North Africa are voluntarily curbing their populations so dramatically that fertility per woman is approaching sub replacement and heading lower over probably the majority of the World population. It is only due to long lifespans that the population is still growing right now.

The sole exception is sub-saharan Africa where some estimates show 50% of human population will live by 2100.

Also once women stop having children societies have all sorts of problems getting that switch turned back on. Even in the US for instance a large measure of population growth is due to immigration. Natural population growth in the USA is only about 0.3% and heading lower. Takes 250 years to double population at that rate.

I don’t see this statement:

as being accurate. Science magazine put out a special issue on population in July 2011 with a map of fertility rates (color-coded countries). In Africa, every country save Tunisia is > 2.2 births/woman, and most are much higher than this. In South America, all but Chile and Uruguay are > 2.2. Central America, the Middle East, India, and central Asia are all colored dark on the map (> 2.2). The fertility rate in developed countries is about 1.7 now (and on an upward trend!). The world average is 2.5.

The populations of many of these countries are so bottom-heavy (majority are young) that even holding fertility to 2/woman in these countries will produce a surge in population as this spate of youngsters reproduce.

So even outside of sub-Saharan Africa, growth by birth is still the norm: it’s not just about living longer.

Yes that was poorly worded. I meant to say the trend lines appear to be headed that way at least for now. Do you know what year that data was from. AFAIK Brazil and Argentina are at replacement. Brazil in particular is at 1.9 children per women per World Bank data.

In less developed countries replacement fertility tends to be higher at 2.3 or 2.4 children per women at present.

The source appears to be the Population Reference Bureau, 2010.

I forgot to add. Take a look at this UN map of world fertility and projected fertility. Growth by birth is not a dominant as you might think.

http://na.unep.net/geas/newsletter/images/Jun_11/Figure5.jpg

They are different strategies – r strategy (quantity) and K strategy (quality). See http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/R/K_selection_theory.

Evolution is a very powerful basis to understand our current predicament, but it is also much complex than we think. Don’t stick to any interpretation too quickly, learn more about evolution. You will see the light.

heh heh

I love it. I get exactly the same technogeewhizzery-outer-space-energy-mining-we’ll-figure-it-out-no-matter-what responses to my exhortations to pay attention that you’ve been getting here.

I’ve concluded there’s no medicine for it, at least nothing rational anyway. I’ve even stolen some of your thermodynamic illustrations in desperation, but to no avail.

I blame it on early exposure to the Jetsons, personally.

🙂

I do want to tell you that I’m enjoying your essays enormously. Happy New Year!

Tom, Thanks for your ongoing Do The Math posts. I do not connect with some of the math, but the lay language rationale is eminently compelling.

Most of us do not realize how highly leveraged our food system is with regard to direct and indirect energy consumption. Here in fly-over country multi-hundred horsepower tractors and a myriad of other energy hungry, labor replacing tools and technologies churn out industrial inputs for our processed food industries and foolish fuels. Rare is the farmer that directly consumes any of the “food” he/she grows.

Todays typical farmer is at the center of a complex of fertilizer suppliers, poisonous herbicides, fungicides, and insecticides, fuel suppliers, bankers, truckers, elevators, food processors and distributors, and refrigeration and freezing storage and distribution systems, to name a few.

As we come off of the energy and other natural resource peaks, food production and affordability will decline dramatically with far reaching consequences for social stability and population reduction. Not that we are not already entering that era…see the current work by Dr. Don Huber re the new to science “entity” associated with GMO crops and the widespread use of glyphostate (http://www.eureporter.co/2011/12/an-unknown-entity-en/, and at http://foodfreedom.wordpress.com/2011/12/20/toxic-botulism-in-animals-linked-to-roundup/). Yikes!

I hope you take a shot at the current disaster we call industrial scale agriculture. If we are to have long term hope for a sustainable food production system it looks like soil building instead of soil destroying agriculture will have to dominate our future. That means organic farming, more animals and people out on the landscape, more local production, seasonally adjusted diets, etc. Talk about needing an attitude adjustment!

We had a back to the land movement about 40 years ago. Today we have much bigger farms and most of the farm homes, barns, wells, etc are gone. Getting people back onto the “homeless” land will in itself present a huge challenge.

Thanks again for your very informative and sobering blogs.

Norm

If we are looking at zero growth societies many examples exist on earth already.

Prominent amongst these are the Pacific islanders. Take Tokelau for instance. Area 10 sqkm. Population 1200 or so. Time settled 1300 years! How is that possible you ask. Tokelauans practice replacement fertility. They have elaborate customs that ensure one is to one replacement. Large chunks of the society are reproductively celibate even is not functionally so. Other unsavory and draconian actions were necessary in the past to control the population to the bearing capacity of the land. Surviving intact for 1300 years is a quite staggering achievement.

Tokelau may have zero *population* growth, but the term growth is used more broadly on these pages to include energy use and economic growth. Many OECD countries have *declining* population. Apparently Tokelau’s economy and energy use are far from primitive.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tokelau#Economy

Yes, things have changed recently as they have in many other places but until 1930 or so they were isolated for 1300 years. So what if they didn’t make it to 1400 years.

Their energy consumption and resources consumption was mostly in balance and sustainable indefinitely.

It is merely a touch stone that it can be done. But do we want to. More pertinently, since it was brought up, do we have the maturity to do what it takes. Including and up to the less tha savory things that will have to be done.

We could “just” switch to bikes, buses, and electric trains! Or at least bikes. Oh wait, that’s one of those grown-up responses. Biking to work in the cold winter is a sure sign that you’re nuts. Or so I’m told as I change my bike headlight batteries again…

And I’m all for paying for checking, as long as everyone does, and the bank executives earn less than the US President. Shoot – shared sacrifice – that’s another of those grown-up things to think.

As for collapsing societies, wouldn’t that be *every* society, except maybe China and Japan, pre-coal? How did the Chinese pull it off? They collected their poo to return to the farm fields, and generally accepted steady state. How did the Japanese? They protected their forests on threat of death. Adults can be harsh. Thanks for helping us think straight.

[shortened by moderator]

Tom,

Some of what you wrote seems like ad hominem argumentation. For example, you claim that your opponents are akin to religious dogmatists, and that you are “blaspheming” or “opposing sacred ideologies” etc.

This tactic of invoking the supposed religious underpinning of one’s opponents is increasingly common these days.

I don’t see anyone who has accused you of blasphemy, or attempted to take down your blog, or censor its comments, or claimed that you have contradicted sacred ideology. Instead, they are making claims relevant to the content of this blog. I haven’t seen anything even remotely resembling religion, or the Church, in any of their claims.

Quite the contrary, I think the “religion” criticism could be more easily leveled against doomsday scenarios. I have noticed that peak oil “doom” scenarios are quite similar to end-of-the-world scenarios which have always been common. For example, they both posit a day of reckoning when apocalypse will finally arrive, and we’ll be punished for our excesses, and disbelievers (which in this case are those who failed to prepare) will perish, and the world will be transformed into a paradise (in this case, a paradise of eco-friendly organic-farming communes that they’ve always wanted). Many followers were hard-left types with serious grievances against industrial civilization anyway. Many were part of the “back-to-the-land” movement in the 1970s, who were disappointed that society had never reverted to manual farming, and who held out hopes for a new “back-to-the-land” movement enforced by oil decline.

And there are many, many other similarities between energy collapse theories and other end-of-the-world scenarios.

But that is all beside the point. You have made mathematical arguments on your blog. Regardless of what I presume your motives to be (in fact I’ve never considered your motives in particular), the arguments stand on their own. Furthermore, the arguments of peak oil doomers also stand on their own, _even if_ they really want the decline. Just because they want the decline doesn’t mean it won’t happen. It’s all too easy to dismiss the arguments of one’s opponents by speculating about what motivates them.

Fair point that I am reacting to an invisible boogey-man. It’s partly comic relief. It’s partly based on arguments I have had with real people in my corporeal life. And DtM has been the target of DDOS attacks on a number of occasions, sometimes succeeding in taking the site offline. Luckily, the black-belt IT guys at UCSD have prevailed and made the site much more robust. And the comments on the why not space post came pretty close to religious belief, in my opinion.

In any case, yes, I am capable of unfair attacks on human grounds. For what it’s worth, I tend to be intolerant of religious attitudes in whatever direction. I am also perturbed by those who say with certainty that the world is collapsing. They also damage my cause—which is to raise collapse as a serious possibility worthy of our focused attention. I too often see casual dismissals of that possibility. If I were forced to pick sides: team A saying things will work out by just letting innovation and market forces and growth play out; or team B saying we must embark on an all-hands effort to save ourselves from collapse, I’ll play with team B. At least if that team is wrong and we end up on a sustainable track as a result of the effort, I’m happy with that outcome. If team A prevails and is wrong, no one wins. My personal experience is that team A is larger and more influential.

As for my motives: I certainly am not pulling for doom scenarios. I’m simply scared by what I perceive to be their real possibility. I would not have started a blog if I didn’t think it was worth my every effort to avoid collapse. First we need to educate ourselves on the scale of the problem, and on options for facing the challenges ahead.

“I certainly am not pulling for doom scenarios. I’m simply scared by what I perceive to be their real possibility.”

After you have understood the scope of the problem, you might wonder for how long we have known. Then you will find out that we had ample time to deal with the problem in a sane way. If you then became a disgruntled doomer who is watching the reality gap in society widen, hoping that it may collapse rather sooner than later, you could be forgiven.

This would definitely reduce your credibility, so I hope you can avoid becoming a doomer. Maybe looking into the future and not thinking about wasted opportunities can help.

Funny article. Its too bad though, people have been trained from since birth to accept wanting more, as right normal and proper. This idea is something pretty much all of us have been conditined to accept at level deeper than thought. Its not as if we were brought up ‘correctly, with a frugal, elgalitarian value set’ then suddenly, at some point, we all took a left turn and became voracious consumer-bots. No, weve ALWAYS been this way. School, media, yes, even our parents, all teach us to be good consumers since day 1. Were are into our what now? 3rd, 4th generation of a pure consumption culture? How do you turn that around on a dime? Unfortunately, human nature being what it is, I suspect the comeing age of shortages will not be perceived by the current generation as an opportunity to set things right, but rather as an excuse to go [crazy], once it becomes clear they cannot keep buying all those toxic plastic garbage,cars etc, they value so much.

Tom, I find it ironic that you are upset by people who will not acknowledge that the future might be inferior to the present. I am upset by young people who get visibly upset when I try to tell them that the past was just as good or better than the present. Other than computers and medicine I haven’t seen anything that stands out to me as being appreciably better. Commercial airliners aren’t much faster, in fact the flight experience is worse and you have to be searched like a criminal besides. Cars have better tires but they’re harder to work on, more expensive to fix and in many cases even get worse gas mileage. I used to be able to drive from Seattle to Bellingham in half the amount of time I spend now and there were no traffic jams. Houses I guess on average now are bigger but the quality of wood and quantity of it is less than in the past and most of them don’t last as long. My parents refrigerator lasted for 30 years, good luck finding ANYTHING that lasts that long now. People are bottoming out their credit trying to live equal to their parents and not being able to admit to themselves that they can’t. Then there are the intangibles that no one wants to be honest about. Such as…more crime, political correctness, too much immigration. Population is growing faster than the solutions. India thinks they are going to populate themselves into prosperity and they are wrong. Africa? Does anyone really see anything getting better? Mankind I am afraid is not going to learn the population lesson without pain. They have already overpopulated and the “wealthy” nations (ha ha) are not going to bail them out. To understand the mindless desire for growth you have only to understand that capitalism is a Ponzi scheme, it depends on more and more people to have vast consumption and pay into the system with taxes. This is of course another lesson that people seem determined to learn only with even more pain.

Jeremy,

You must be careful of the “good old days” phenomenon where people mis-remember the past and treat their own childhoods as a golden age. This effect is a frequently studied bias in Psychology.

Of course you can give examples of things that have gotten worse, but you must be careful of selective examples.

[moderator removed lengthy point-by-point counter-arguments to the effect that many of Jeremy’s “worse now” items are flawed.]

…When I was a teenager, there were 12 TV channels, nobody had a VCR, long-distance phone calls were about 20x more expensive and so were infrequent, nobody had a computer (much less an internet connection), lightbulbs used 100 watts, cell phones didn’t exist, airline travel was for rich people, cars didn’t have air conditioning and most houses didn’t either, you couldn’t get any medical procedure more complicated than an X-Ray, music was on analog equipment (which believe me did NOT sound better unless you paid a fortune), clothing was about twice as expensive in real terms (and it didn’t last longer) than now, everyone worried about nuclear war with the USSR destroying the entire world, and Herman Daly and Charles Hall were predicting imminent energy collapse, which I admit is the same as now.

Obviously I’m purposefully selecting things which have gotten better (or stayed the same). In response, I’m sure you can come up with many examples of things which have gotten worse. Which ones we see, mostly depends on which ones we’re looking for.

Civilization-ending nuclear weapons and their specialized delivery systems have only been around for ~60 years, and countries are still interested in building them. To be sure, I don’t cower in a bomb shelter surrounded by canned beans and iodine tablets, but we could use a dose of Cold War-era nuclear paranoia from time to time, just to remind ourselves of how we’ve booby-trapped the planet with h-bombs and fleets of ballistic missile submarines.

With respect to Hall, Daly, Meadows, etc., I take the same sort of long view: we still have plenty of time to screw things up, and our highly-globalized, fossil fuel-dependent industrial civilization hasn’t been around all that long.

[moderator removed lengthy point-by-point counter-arguments to the effect that many of Tom S’s “better now” items are flawed.]

I do not “misremember” the past. I have experienced it and experienced the present. I do not think I lived in a golden age. But there is a difference between a bad head cold and Ebola virus. [We need to stop] looking at the toys and look at the substance. Everyone is starting to sense that something is fundamentally ill in America right now but no one wants to hear it confirmed. This has been building for decades and denial isn’t going to cure it.

Jeremy,

“I do not ‘misremember’ the past. I have experienced it and experienced the present.”

You definitely do misremember the past, because we all do. Human memory is not like a slideshow, where everything is retained perfectly and weighted equally. Instead, people have _selective recall_ based upon their emotional state, and based upon many other cognitive biases, and recall biases. This topic is extensively researched in Psychology.

If memory were unbiased, then people of different temperaments would _agree_ on these things. But they do not: there are many techo-optimists who insist that everything is far better and the rate of improvement is increasing. Whose memory should I trust?

“Stop looking at the toys and look at the substance…”

Ok. If I look at statistics (not personal recall!) of: life expectancy, living space per capita, average educational attainment, and costs of various essential things, like food, natural gas, electricity, living space, and vehicular transport (adjusted for the median wage), these things have remained flat, or undulated, or improved modestly since 1978. Two metrics have gotten worse: hours worked and personal debt, most of which went to paying for expensive medical treatments which weren’t available in 1978.

“Everyone is starting to sense that something is fundamentally ill…”

How did you determine what “everyone” is starting to sense? Be careful about this, especially if you spend any fraction of your time in peak oil forums.

Of course, I don’t just mean you. I also have unrepresentative experiences and biased recall, and so does everyone else.

Okay—I’ve let the spat go on longer than it should. That’ll be it.

Well, we need much more nanotechnology so that we can make these cool solar cells, recycle our garbage, make new things, fix our cells (eliminating aging, boosting our brains etc)…AND WE NEED to do this by getting rid of all the worlds miltaries and the meme that militaries are cool etc.

Problem solved, now get back or work……….

Here is a 40 year old glimpse of what we might need to do to avoid a painful collapse, done in a DtM fashion. http://ocw.mit.edu/courses/sloan-school-of-management/15-988-system-dynamics-self-study-fall-1998-spring-1999/readings/behavior.pdf

This research has been updated several times since to keep pace with actual events, but it’s trends are broadly on the mark. Congress didn’t listen in 1971, and human nature says that it won’t listen until the worst of the trends are apparent to everyone. Our trend towards collapse is old news, our denial of it continues as a current event.

If we acknowledge that a massive ‘correction’ is coming (not the end times or armageddon or the apocalypse) and that we probably won’t act collectively until it is too late to avoid the correction, that leaves us with individual action – building our resilience so that our families and immediate communities are on the survival side of the ledger. Then we become the seeds for an appropriate collective response, which will come in due course.

Tom is right, we need to get past our reticence to even say the word collapse and start talking about how to cope. We need to do the math.

I’ve been telling some people about DO THE MATH and how Murphy puts the numbers on various daydreams about how to solve our delimma. To explain I do the arithmetic on a conversation I had back in 2008 with a blackberry plant customer here at my farm. We were having a little chat after we got settled up and got his plants loaded. This fellow had some country in him but he appeared to be making good money at the time. He had one of those deluxe pickups and nice clean clothes. He said he worked for a grocery chain as computer programmer. The price of gasoline came up and he said there was only three days inventory in those grocery stores and that if

“those trucks ever stop running there won’t be a dog or cat anywhere inside of a week.”

I respected his grasp of the situation at the time and that respect has only increased since then. After I started reading Murphy I thought about doing the math on those dogs and cats. I don’t know much math but I can do some arithmetic on my calculater. So I looked it up and The Pet Food Institute estimates that there are 75 million dogs and 85 million cats in the US. I rounded off the US population to 313 million people and divided into 75 million dogs and got .2396 dogs per person. And I divided 85 million cats by 313 million people and got .2715 cats per person.

So if the stores are cleaned out in 3 days and we start in on the dogs and cats, does approximately a quarter of a dog and a quarter of a cat seem reasonable for 4 days of food for the average American.

I’m not sure about that but it would probably beat no food for 4 days.

I’m amazed at some of the comments that come in here. The professor is trying to point out that this is serious business. The numbers don’t add up for the US lifestyle. Fission power plants and greenhouses on Mars aren’t going to put food on the table for 10 billion people. Something’s got to give.

I would have to disagree that people just want “more stuff.” If so, are they happier now than 100 years ago? I’d be happy with enough food to stave off hunger, enough friends to ward off loneliness, enough co-operation to solve my community’s local problems, and enough MEANINGFUL work to prevent lethargy and soullessness. Video games, sit-coms on TV, a flashy new car, and digital gadgets are distractions to a well-lived life. The energy wasted on all that baggage is what’s destroying the air we breath, the environment we depend on for our survival, and the bonds we once had with each other. The net energy cliff could be the impetus we need to reconnect with what really is important to us on this planet.

Tom,

Two references you might find interesting. This article has a number of asides that cast the “space cadet” dynamics in a larger context:

http://www.thenation.com/article/164497/capitalism-vs-climate?page=full

The glibertarian view of space is that it backstops the abundance of Earth with the abundance of the universe – even if the former would ever limit our ambitions, the latter will allow for business as usual. In reality, the resource scarcity of space you illustrated would make the issues Klein described come to the fore much sooner than we are – now – seeing them become obvious on a global scale. The underlying conflict is that of cornucopia – there is more then enough, nobody will give it to you, you “just” gotta take it – vs. the lifeboat.

The key claim of the other article: “The Holocene never supported a civilisation of 10 billion reasonably rich people, as the Anthropocene must seek to do, and there is no proof that such a population can fit into a planetary pot so circumscribed.”

http://www.economist.com/node/18741749

I think you might find both of these relevant to your upcoming analysis of nuclear fission as a possible part of any interim solution to what will eventually become Peak Energy.

[lengthy discussion of nuclear removed; promise to get to nuclear soon]

Indeed, I referenced the same Nation article in the main post. It is certainly worth the read–thanks.

This is so boring. Same nonsense for 1000s of years about natures bounty not being enough to sustain man’s needs, Roman philosophers were the first ones to be wrong, many followed.

You.. Don’t.. Get.. It..

When a normal theory has been falsified for 100s and 100s of times, it gets rejected and another will be found. Not the Peak “Resource” theory; it apparently is infallible.

Until you understand that the only resource that matters to mankind is the human brain, you will never be able to understand the past nor the future.

You will never understand that resources; metals and fossil fuels, become cheaper on the long run, as they measurably have since the middle ages. You’ll never understand why people have never been better fed. Or why energy use has been rising since the beginning of history. That although there where never this many people, we’ve never had it this good in history and pre history ever before.