This is the fourth of about 17 in the Metastatic Modernity video series (see launch announcement), putting the meta-crisis in perspective as a cancerous episode afflicting humanity and the greater community of life on Earth. This episode addresses the more subtle and under-appreciated aspects of evolution, which acts on the whole community of life in full ecological context.

As is the custom for the series, I provide a stand-alone companion piece in written form (not a transcript) so that the key ideas may be absorbed by a different channel. The write-up that follows is arranged according to “chapters” in the video, navigable via links in the YouTube description field.

Introduction

This is the usual 10-second naming of the series, of myself, and the topic of this episode (evolution) as part of the process for putting modernity into context.

Evolution Basics

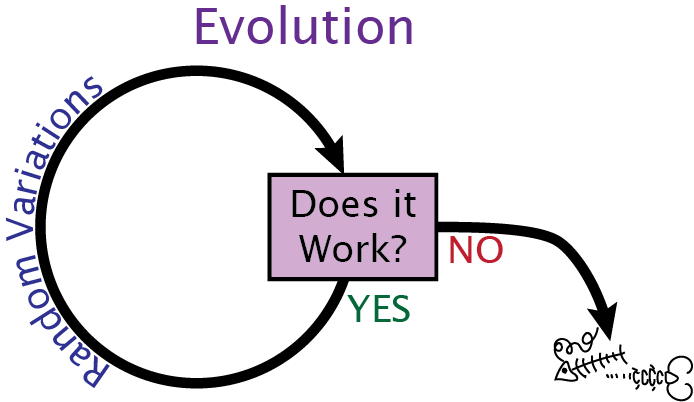

Because almost everyone knows something about evolution, I spend very little time on the basics so that more time can be spent on the subtle and under-appreciated aspects of the subject. I do, however, provide an overview using the diagram below.

Evolution is simple, elegant, and essentially circular: If it works, it works. Any organism participating in the game of life is constantly being evaluated on this simple basis: if you work, you can stay around, and if you don’t work—well, you’re out of the game. It’s a very simple process that really has no choice but to operate in conjunction with life. Random mutations and variations along the way haplessly try new things that will be judged by overall effectiveness.

Works: Definition

We need to better define what it means to “work” in this sense. Obviously, a large enough number of individuals need to acquire energy (food) and survive long enough to reproduce in order to meet the criterion of being selected for “success.” That’s the outer, most obvious layer of “working.”

The main point of this episode is that far beyond individual-level selection, evolution works in a full ecological context—in relation to all other life. It’s not operating on isolated species, but on everything at once in a massively parallel approach.

Among other considerations, an organism has to participate in the local nutrient cycle in order to acquire the requisite atoms (hydrogen, oxygen, carbon, nitrogen, phosphorous, sodium, etc.—see post on inexhaustible flows). These cycles have been worked out by evolution over millions and billions of years, only tolerating life forms that don’t require exotic materials. Any organism only “works” in the long term if it taps into and donates to these flows, approximately in equal measure.

Whether something “works” or not is also evaluated over a very long timescale—in the million-year ballpark. This is the scale of longevity for successful species.

Nothing in Isolation

Having been “brought up” in modernity, we are trained to separate concepts. Divide and conquer. Establish disciplinary specialties. Stay in your lane. Break it down. Such an approach has been very effective in understanding the building blocks of our world, and is the primary skill emphasized in education today. We have far less practice in systems-thinking and appreciation of the complex, unfathomable, interconnected whole.

Take the adorable Douglas squirrel, for instance, with its tawny orange belly. We think of the squirrel in isolation, as a genetically separate entity unto its own. But the squirrel could not exist in isolation because it completely relies on mushrooms, tree seeds (cones, acorns, maple), and bugs to eat. It also needs the tree for safety, shelter, and nest materials. The squirrel can’t exist without those other forms of life (not to mention the sun, air, water, gravity, rock, ocean, and all the rest). Nothing stands alone. You are as likely to find an isolated human eyeball wandering about as to find a squirrel population without its supporting web.

Complex Inter-relationships

Relationships go the other way, too: the tree needs the squirrel for planting its seeds, the mushroom for exchanging nutrients in the soil, and insects for pollination and other services. Thus, many two-way, three-way, and many-way relationships exist. But it does not stop there, because the web just gets bigger and bigger. Every species depends on other life.

The interrelationships go all the way down to microbes—important in both soils and digestive tracts. As a result, it is not meaningful to speak of the squirrel without worms tending the soils for the trees. The dependency may not be direct, but that’s exactly the point: most dependencies are indirect but no less crucial (with some resiliency). It’s all one interconnected web that has co-evolved together as a sort-of package. The myriad inter-dependencies and relationships are too numerous and complicated for us to fully track. One might view squirrels as the “fruiting body” of a healthy forest: one component of a whole, each species serving the others in some way that has been established in a long-running relationship.

Competition Overemphasis

Our culture over-emphasizes the competitive side of evolution. We think in terms of winning—perhaps because we fancy ourselves as having “won” the game of evolution (grow up!).

To be sure, evolution involves many examples of competitive “arms races,” whereby incremental improvements in one species must be countered by compensating improvements in another in order for the aggregate to still work in approximate balance. So, yes, competition has driven a great deal of evolutionary change. But it is the obvious layer. It doesn’t stop there.

Cooperation is also a powerful agent. Evolution does not set any rules on what strategies might be tried: if it works, then okay! This leaves plenty of room for mutual benefits (symbioses). This is part of how nutrient cycles are realized. Some species help each other, and many absolutely rely on each other: “my survival depends on your survival.”

Multi-cellular Cooperation

Multi-cellular life was a fascinating early example of cooperation starting 1.5 billion years ago. Member cells no longer operated in a “looking out for Numero Uno” sort-of way, instead working with other cells toward a collective goal.

Thus, the cells in our bodies are not competitive with each other, and nor are our organs—when healthy.

Organ Analog

The organ analog is useful here. The heart, kidneys, pancreas, and lungs are not competitive, but cooperative. Each has its niche role in the body, and none could function in isolation without all the other organs. The liver and intestine need each other.

Ecological communities are similar: all play a role and all need each other in some way because that’s how the whole thing works. Whether organs or species: they all evolved together, in relationship, as part of a package, sharing a common goal of surviving. Any collection of organs or organisms that can survive for millions of years at a time—slowly changing and always in relationship—is testament to the fact that the arrangement works in the context of that particular package (other variants are not guaranteed to work).

In this analogy, cancer is associated with a rogue organ that is no longer working in cooperation with the rest of the system, but draining resources while inflicting harm on itself and other organs. It is effectively at war with the organism. The cancer is not vetted by evolution to be part of a “working” arrangement. It will not work long-term: it’s self-terminating. We will return to this theme in the context of modernity later in the series.

Survival of the Fittest?

“Survival of the fittest” is a phrase we often hear in connection with evolution. Okay, it has a solid basis, but by itself misses the larger point. What does “fittest” even mean? The construct belies our tendency to separate (divide and conquer) so that we conceive of the squirrel as an isolated entity that could “win” if it just had sharper teeth, better hearing, greater stamina, a larger brain for remembering food storage, etc.

But in an ecological context, an adaptation that is too successful becomes counterproductive. A squirrel that remembered every stored nut would fail to inadvertently plant the next generation of trees, so that after a few decades of “crushing it” in their memory games, the forest would be gone and with it the squirrels. That particular squirrel adaptation would be ruled a failure, so we end up with squirrels that work. Similarly, becoming too successful at hunting prey risks wiping out the prey and thus yourself. Why don’t we have an organism simultaneously boasting the best eyesight, best hearing, best sense of smell, infrared vision, echolocation, magnetic field sensing, and all the rest? This “super-predator” would be so far out of balance as to be self-defeating. So much for the “fittest.”

There is no such thing as “winning” in a complex community of life. It’s not a competition. If you think you’re winning, it’s probably a sign that you’re engaged in the slower and larger process of losing.

As an aside, I personally view the emphasis on “survival of the fittest” as a reflection of the macho, capitalist, winner-take-all, supremacist, market-competitive, selfish culture we have constructed. I could trace it back to early agriculture and its associated domination of the land, other animals, and other humans. This “mantra of evolution” is therefore heavily influenced by our distorted values within modernity.

Survival of the Best-Fitting

Seen through an ecological lens, a better approach is “survival of the well-integrated,” or perhaps “survival of the best-fitting“—although the word “best” is still problematic. A better choice might be “suitably-fitting.” The “fit” is then judged in relation to the encompassing community of life, as it must be.

All in this Together

The only valid way to appreciate the situation is to recognize that we are all in this together. No species got here on their own merits alone: that’s not a thing. It was all co-evolution in full ecological context, fully reliant on the rest of the web of life at every step. Every species jointly benefited from countless inter-dependencies at multiple orders of removal, as it could not have been any other way. Modernity’s specialty of linear, serial thinking is not as powerful a tool in this context as it might be in designing a computer’s communication protocol or in constructing an elegant mathematical proof or calculating material requirements for a skyscraper to withstand wind load. Rocket science is comparatively dumb.

Our superficial understanding of relationships is never going to be complete. Nor should this be the goal or be considered to be necessary. It is enough to appreciate that it’s complicated, and approach the matter with awe and respect.

Part of the reason we shouldn’t expect to master it all is that these relationships were developed over millions and billions of years. The selection pressures that led to our brains would not be expected to produce brains capable of penetrating every ecological relationship on Earth. Much will remain mysterious, and that’s okay!

Evolution has no choice but to simultaneously work on the whole set of species and their inter-relationships. Evolution does not work on the squirrel by itself or the insect by itself with no interaction between them: it can’t work like that. Evolution always operates on the full ecological context. Have I said that already?

Closing and Do the Math

Next time we’ll look at humans’ biological inheritance. I make an appeal for folks to look at the companion write-ups on Do the Math, as I say in the video that “I’m better in writing.” It’s a case-in-point: “I look better on paper” would be the preferred way to write that sentiment.

Views: 2248

Thank you for publishing these summaries of the videos for those of us who prefer the written word!

I can't help myself. After I record the video I think of all the ways I could say things more clearly. But if I reversed the process and recorded videos reading off a list of points and optimized phrasings, I couldn't pull it off as natural, conversational, unscripted (because it wouldn't be).

Tom, are you familiar with the work of Iain McGilchrist? His understanding of what's happening these days dovetails into what you and others have been saying. I think you will appreciate it. Here's a link to an article I wrote that briefly summarizes his book, "The Master and His Emissary."

https://medium.com/literary-impulse/left-brain-world-e1fb29a6b9fa?sk=e601b23e5f70ad62150c8db23009188c

Indeed, I have been heavily influenced by The Master and His Emissary, and have mentioned it in passing in posts over the last year or so. I started reading it a second time, taking careful notes, but got stalled in the process. In any case, I derive a great deal of insight into different modes of thinking, and the narrow failures of the dominant analytical, logical, certain, reductionist ways of thinking. It helped me understand why I was always so different from colleagues: sure, I was cracker-jack at analytical thinking, but always rich in contextual links to many domains. I think it does capture a significant failure mode of modernity, and helps explain why ecological interconnectedness has become so alien to us (while obvious to cultures modernists would call primitive).

I will caution that I am not a fan of the later work (The Matter with Things), which appears to me to try to come up with a left-hemisphere analytic, abstract re-presentation of reality that I find to be a little bizarre. But the Master/Emissary book is fabulous—except to imply that the Renaissance was a balanced time: it, and the other two example European periods, were woefully ecologically imbalanced—all part of post-agriculture modernity as self-styled masters/owners of the world.

Yeah, I agree that his example of balanced societies is puzzling. There are other flaws as well, notably that his governing metaphor for the title is so strongly male dominant. Not that I'm a fan of political correctness, but he pretty much ignores the whole matriarchal/patriarchal thing. Nonetheless, it's an intriguing notion. As always, I'm looking forward to your next offering!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dFs9WO2B8uI

A short RSA Animate presentation of Iain McGilchrist ideas.

Thank you! An excellent 12 minute recap. A left hemisphere summation/reduction of the importance of the right hemisphere and balance!

I find it quite interesting that evolution was discovered by a very anthropocentric culture. I wonder how animist cultures view evolution.

Modernity will undo itself in a number of ways… A common thread in animist/indigenous cultures is a sense of deep kinship to all other living beings. Some call plants and animals "our older brothers and sisters, who have much to teach us about how to live in this world." It's virtually impossible to look at a raccoon hand and not see your own. Body plans are so similar among so many animals. Even a fly has a head and eyes and mouth. It may be more a matter that the human supremacism that flowed from agricultural domination obscured what was obvious to many others.