Surfing YouTube, I came across an interview of Ezra Klein by Stephen Colbert. He was promoting a new book called Abundance, basically arguing that scarcity is politically-manufactured by “both sides,” and that if we get our political act together, everybody can have more. Planetary limits need not apply. I’ve often been impressed by Klein’s sharp insights on politics, yet can’t reconcile how someone so smart misses the big-picture perspectives that grab my attention.

He’s not alone: tons of sharp minds don’t seem to be at all concerned about planetary limits or metastatic modernity, which for me has been a source of perennial puzzlement.

The logical answer is that I’m not the sharpest tool in the shed. Indeed, many of these folks could run cognitive/logical circles around me. And maybe that’s the end of the story. Yet it’s not the end of this post, as I try to work out what accounts for the disconnect, and (yet again) examine my own assuredness.

Imagined Basis

What is the basis of pundit-level rejection of my premise? Oh yeah: my premise is that modernity is a fleeting, patently unsustainable mode of life on Earth that will self-terminate on a historically relevant (i.e., brief) timescale—likely to convincingly crest the peak this century. Modernity can’t last.

I will reconstruct how I think an ultra-smart person might react, were I to present in conversation the premise that modernity can’t last—based on past interactions with such folks. Two branches stand out.

One branch would be the unwittingly spot-on admission of “I don’t see why not.” I could not have identified the core problem any better, and would be tempted to say: “Wow—what a courageous first step in recognizing our limited faculties. That humble confession is very big of you.” My not having the wit to prove conclusively to such folks that modernity can’t work (and I would say that no human possesses such mental powers) says very little about the complex reality of our future—operating without giving a flip as to what happens in human brains. But it’s also quite far from demonstrating convincingly how something as unsustainable as modernity—dependent on one-time exploitation of non-renewable resources—might possibly address the host of interacting elements that will contribute to its crumbling.

That branch aside, the common reply I want to spend more time on goes something like: “Just look at the past. No one could have foreseen the amazingness of today, and we ought to recognize that we are likewise ill-equipped to speculate on the future. In other words, anyone expressing your premise in the last 10,000 years would have turned out to be wrong [well, so far]. Chances, are: so are you.”

Damn. Blistering. How can one get up from that knockout? And the thing is, it’s a completely valid bit of logic. I also appreciate the intellectual humility involved. Why, then, am I so stubborn on this point? Is it because I want to be popular or rich? Then I’m even stupider than I thought, because those things are basically guaranteed to be incompatible with such a message. Is it because I crave end-times, having been dealt a bad hand and never “good at the game?” Nope: I thrived as an all-in astrophysicist and had/have a rather privileged and comfortable life that I would personally, selfishly prefer not to have disrupted. Is it out of fear of collapse? Getting warmer: that was a big early motivation—the alarming prospect of losing what I held until recently to be a glorious civilization. But at this point all I can say is that based on multiple lines of evidence I really think it’s the truth, and can’t easily or honestly argue myself out of this difficult spot. Denial, anger, bargaining, and depression don’t help us come to terms with the hard reality..

Returning to the putative response: I’ll name it as lazy. It’s superficial. It’s a shortcut, sidling up to: “Collapse hasn’t happened yet—in fact quite the opposite—and thus most likely will not.” It declines to examine the constituent pieces and arguments, falling back on a powerful and persuasive bit of logic straight out of the left brain. It has all the hallmarks: certain, crisp, abstract, decontextualized, logical, clever.

It carries the additional dual advantage of simultaneously avoiding unpleasant confrontation of a scary prospect and inviting starry-eyed wonder at magic the future might bring. No wonder it’s so magnetically attractive as a go-to response!. We’re both driven to it and attracted by it! The very smartest among us, in fact, often have the most to lose, and may therefore be among the most psychologically attached to modernity. We mustn’t forget that every human has a psychology, and is capable of impressive levels of denial for any number of reasons.

Some Metaphors

Its time for a few metaphors that help to frame my approach. I offer two related ones, because none are perfect. Together, they might work well enough for our purposes.

Take One

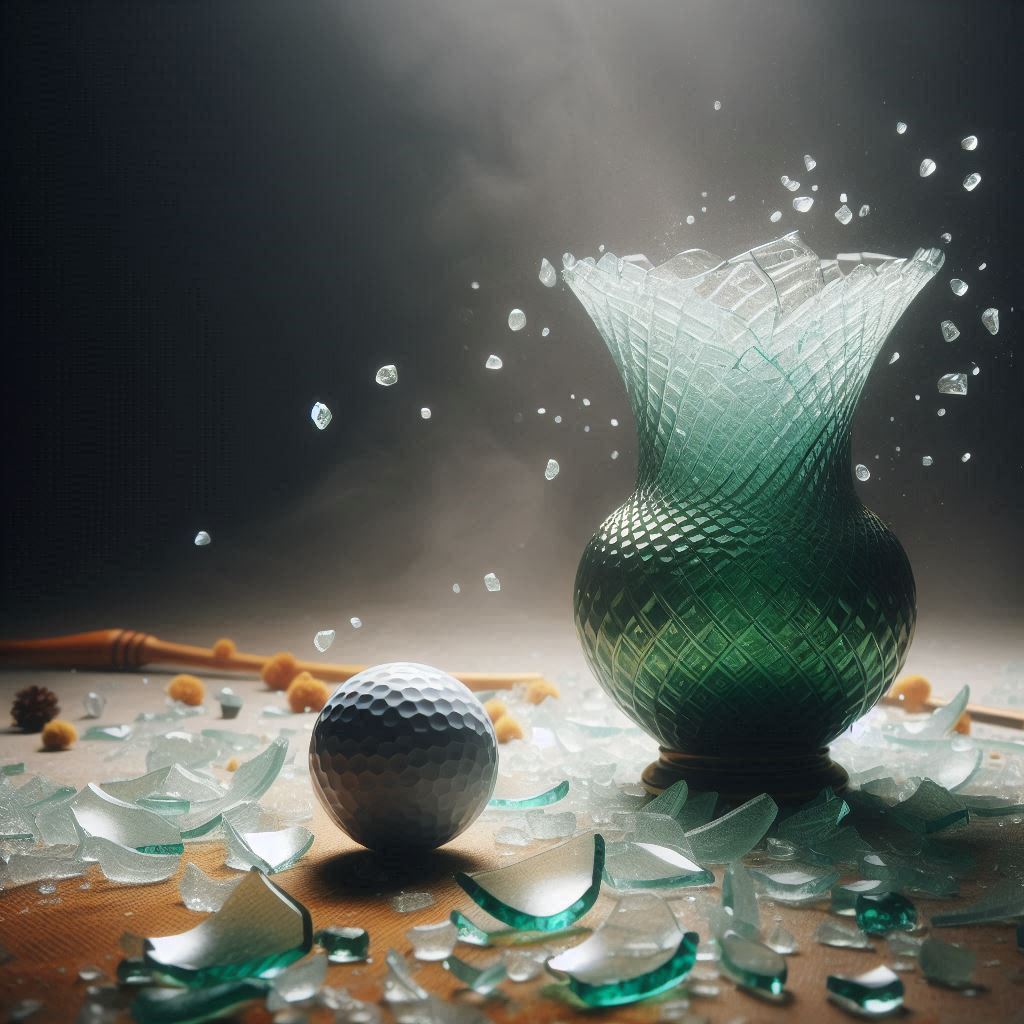

Imagine that someone tees up a golf ball in an indoor space full of hard objects: concrete walls and steel shelves—maybe loaded with heavy glass goblets and vases, etc. Poised to deliver a smashing blow to the ball with an over-sized driver, they ask me: “What do you think will happen if I hit this ball?” Imagining a comical movie scene where the ball makes a series of wild-ass bounces shattering priceless collectables as it goes, it might seem impossible to guess what all might or might not happen. So, I “cheat” and say: “The ball will come to rest.”

And guess what: I’m right! No matter how crazy the flight, it is guaranteed that in fairly short order, the ball will no longer be moving. I could even put a timescale on it: stopped within 10 seconds, or maybe even 5—depending on the dimensions of the room. I can say this because each collision will remove a fair bit of energy from the ball, and the smaller the room, the shorter the time between energy-sapping events.

During the middle of the experiment, it is clear that mayhem is happening, and it’s essentially impossible to predict what’s next. That’s where we are in modernity. So, yes: some intellectual humility is called for. We could not have predicted any of the particulars, after all. But one can still stand by the prediction that the ball will come to rest, much as one can say modernity will wind itself down.

Take Two

The golf ball metaphor does 80% of the work, but I don’t fully embrace it because the ball is at maximum destructive capacity at the very beginning, its damage-potential decaying from the first moment. Modernity took some time to accelerate to present speed, now at a fever pitch. For this, I think of a rock tumbling down a slope.

I do a fair bit of hiking, sometimes off trail where—careful as I am—I might occasionally dislodge a rock on a steep slope. What happens next is entirely unpredictable (even if deterministic given initial conditions). Most of the time the rock just slides just a few centimeters; sometimes it will lazily tumble a few meters; or more rarely it will pick up speed and hurtle hundreds of meters down the slope in a kinetic spectacle. Kilometer scales are not entirely out of the question in some locations.

Still, for all these scenarios, I am sure of one thing: the rock will come to rest—possibly in multiple fragments. I can also put a reasonable timescale on it, mid-journey, based on its behavior to that point. I can tell if it’s picking up speed. I can evaluate if the slope is moderating or will soon come to an end. It’s not impossible to make a decent guess for how long it might go, even if unable to predict what hops, collisions, or deflections it might execute along the way.

Maybe the phrase “a rolling stone gathers no moss” can be re-interpreted as: kinetic mayhem is no basis for a healthy, relational ecology. If tumbling boulders were the normal/default state of things, mountains would not last long (or more to the point: never come into being!). Likewise, one species driving millions of others to extinction in mere centuries is not a normal, sustainable state of affairs. That $#!+ has to stop.

Modernity’s Turn

Modernity is far more complex than a tumbling rock. But one side effect of this is a multitude of facets to consider. When many of them line up to tell a similar story…well, that story becomes more compelling. I offer a few, here.

Population

Global human population has been a super-exponential, in that the annual growth rate as a percentage of the total has steadily climbed through the millennia and centuries (0.04% after agriculture began, up to 2% in the 1960s). It is no shock to anyone that we may be straining (or overtaxing) what the planet can support. Indeed, the growth rate has been decreasing for the last 60 years, and the drop appears to be accelerating lately. Almost any model predicts a global peak before this century is over, and possibly as soon as the next 15–20 years. This is, of course, highly relevant to modernity. Economies will shrink and possibly collapse (being predicated on growth) as population falls from a peak. Such a turn could precipitate a whole new phase that “no one could have seen coming.” I’m looking at you, pundits!

The argument of “just look to the past” and imagining some sort of extrapolation begins to seem dubious or even outright silly in the context of a plummeting population. Let’s face it: we don’t know how it plays out. Loss of modern technological capabilities is not at all a mental stretch, even if such “muscles” are rarely exercised.

Resources

Modernity hungry!. Fossil fuels have played a huge role in the dramatic acceleration of the past few centuries. We all know this is a limited-time prospect. Oil discoveries peaked over a half-century ago, so the writing is on the wall for production decline on a timescale of decades. Pretending that solar and wind will sweep in as substitutes involves a fair bit of magical thinking and ignorance of myriad practical details (back to the “I don’t see why not” response). We face an unprecedented transition as fossil fuels wane, so that the acceleration of the past is very likely to run out of steam. Even holding steady involves an unsubstantiated leap of faith—never fleshed out as to how it all could possibly work. “I don’t see why not” is about the best one can expect.

Mined materials are likewise non-renewable and being consumed at an all-time-high rate. Ore grade has fallen dramatically, so that we now must pursue increasingly marginal and deeper deposits and thus impact more land, while discharging an ever-increasing volume of mine tailings. This happened fast: most material extraction has occurred in the last century (or even 50 years). We would be foolish to imagine an extrapolation of the past or even maintaining similar levels of activity for any long duration. More realistically, these practices will be undercut by declining population and energy availability. I’ve spent plenty of time pointing out that recycling can at best stretch out the timeline, but not by orders of magnitude.

Water/Agriculture

Agricultural productivity has also steadily increased, but on the back of “mining” non-renewable resources like ground water and soils—not to mention an extraordinary dependence on finite fossil fuels. Okay: at least water and soils can renew on long timescales, but our rate of depletion far outstrips replenishment. Land turned to desert by overuse stops even trying to maintain soils, while also suppressing water replenishment by squelching rainfall. This is yet another domain where the fact that the past has involved a steady march in one direction is quite far from guaranteeing that direction as a constant of nature. Its very “success” is what hastens its failure. The simple logic of “hasn’t happened yet” blithely bypasses a lot of context sitting in plain sight.

Climate Change

I don’t usually stress climate change, because I view it as one symptom of a more general disease. Moreover, should we magically eliminate climate change in a blink, my assessment is hardly altered since so many other factors are contributing to the overall phenomenon of modernity’s unsustainability. I include climate change here because it seems to be the one element that has percolated to the attention of the pundit-class as a potential existential threat. It isn’t yet clear how modernity trucks on without fossil fuels. Yet, even if we were to curtail their use by 2050, the climate damage may be great enough to reverse modernity’s fortunes (actually, the most catastrophic legacy of CO2 emissions may be ocean acidification rather than climate change). Again, the “logic” of extrapolation becomes rather dubious. The faith-based assumption is that we will “technology” our way out of the crisis, which becomes perfectly straightforward if ignoring all the other factors at play. Increased materials demand to “technofix” our ills (and the associated mining, habitat destruction, pollution) puts a fly in the ointment. But most concerning to me is what we already do with energy. Answer: initiate a sixth mass extinction by running a resource-hungry, human supremacist, global market economy. Most climate change “solutions” assign top priority to maintaining the destructive juggernaut at full speed—without question.

Ecological Collapse

This brings me to the ultimate peril. As large, hungry, high-maintenance mammals on this planet, we are utterly dependent on a healthy, vibrant, biodiverse ecology—in ways we can’t begin to fathom. It’s beyond our meat-brain capacity to appreciate. Long-term survival at the hands of evolution has never once required cognitive comprehension of the myriad subtle relationships necessary for a stable community of life. An amoeba, mayfly, newt, or hedgehog gets on just fine without such knowledge. What is required is fitting into the niches and interrelationships patiently worked out through the process of evolution. Guess what: in a flash, we jumped the tracks into a patently non-ecological lifestyle not vetted by evolution to be viable. It appears to be not even close.

This is not just a theoretical concern. Biologists are pretty clear that a sixth mass extinction is underway as a direct result of modernity. The dots are not particularly hard to connect. We mine and spew/dispose materials alien to the community of life into the environment. Good luck, critters! We eliminate or shatter wild space in favor of “developed” land: exterminating, eradicating, displacing, and impoverishing the life that depends on that land and its resident web of life. The struggle can take decades to resolve as populations ebb—generation after generation—on the road to inevitable failure. Even this decades-long process is effectively instant compared to the millions of years over which the intricate web was crafted.

I have pointed out a number of times that we are now down to 2.5 kg of wild land mammal mass per human on the planet. It was 80 kg per person in 1800 and 50,000 kg per person before the start of the agricultural revolution—when humans held a roughly proportionate share of mammal biomass compared to the other mammal species. In my lifetime (born 1970), the average decline in vertebrate populations has been roughly 70%. Fish, insects, birds decline at 1–2% per year, which compounds quickly. Extinction rates are now hundreds of times higher than the background, almost all of which has transpired in the last century.

Just like the golf ball in the room or the rock tumbling down the mountainside, these figures allow us to place approximate, relevant timescales on the phenomenon of ecological collapse—and that timescale is at the sub-century level. We’re watching its opening act, and the rate is alarming. The consequences, however, are easily brushed aside in ignorance. Try it yourself: mention to someone that humans can’t survive ecological collapse and—Family Feud style—I’d put my money on “I don’t see why not” being among the most frequent responses.

So, Don’t Give Me That…

I think you can see why I’m not swayed by the tidy and fully-decontextualized lazy logic of extrapolation offered by some of the smartest people. This psychologically satisfying logic can have such a powerfully persuasive pull that it short-circuits serious considerations of the counterarguments. This is especially true when the relevant subjects are uncomfortable, inconvenient, unfamiliar, and also happen to be beyond our capacity to cognitively master. Just because we can’t understand something doesn’t render it non-existent. Seeking answers from within our brains gets what it deserves: garbage in—garbage out.

We used the metaphors of a golf ball or rolling stone necessarily coming to rest. Likewise, a thrown rock will return to the ground, or a flying contraption not based on the aerodynamic principles of sustainable flight will fail to stay aloft. Modernity has no ecological context (no rich set of evolved interrelationships and co-dependencies with the rest of the community of life) and is rapidly demonstrating its unsustainable nature on many parallel, interconnected fronts. This would seem to make the default position clear: modernity will come to rest on a century-ish timescale, the initial reversal possibly becoming evident in mere decades. [Correction: I think it will likely be mostly stopped on a century timescale, but it may take millennia to fully melt into whatever mode comes next.]

Retreating to the logic of extrapolation or basic unpredictability amounts to a faith-based approach that deflects any actual analysis: a cowardly dodge. Given the multi-layer, parallel concerns all pointing to a temporary modernity, it would seem to put the burden of proof that “the unsustainable can be sustained” squarely on the collapse-deniers. The default position is that unsustainable systems fail; that non-ecological modes lack longevity; that unprecedented and extreme departures do not become the rule; that no species is capable of going-it alone. Arguing the extraordinary obverse demands extraordinary evidence, which of course is not availing itself.

When logic suggests an attractive bypass, recognize that logic is only a narrow and disconnected component of a more complete, complex reality. Most importantly, the logic of extrapolation only serves to throw up a cautionary flag, without even bothering to address the relevant dynamics. That particular flag is later recognized as a misfire once the appropriate elements are given due consideration: this time is different, because modernity is outrageously different from the larger temporal and ecological context. Pretending otherwise requires turning a spider’s-worth of blind eyes to protect a short-term, ideological, emotionally “safe” agenda. Pretend all you want: it won’t change what’s real.

Views: 5938

Yes. The main driving pistons of the machine will come to a rest within a century or so. But the myriad wheels-within-wheels will continue spinning, expending their momentum for quite some time; as you say, perhaps a millennia or more. But I don't look at the end of Modernity as a death knell; I see it rather as an extended introduction to the next act. I find it exciting to think about the new epics that will be written during this next millennia, the new works of art produced, new forms of music and dance and expression, new ways of regarding one another as human creatures and living together on a planet filled with other lifeforms. I know many folks think we are stuck, condemned to the will of 'human nature,' doomed to forever repeat our mistakes. And I know we are at the brink of our own extinction. It keeps me awake at night. But we shouldn't discount the possibility that we will change in ways we can't imagine; and who's to say the changes won't be for the better?

Well put, and I share this excitement. Let's get this modernity thing over so we can usher in a more lasting and healthy phase…

Murmurations ((mighty flocks of birds) appear to be following ‘air path’ that no individual member of the flock predicts or chooses. In recent book Neil Theise recognizes the murmuration-like pattern in human modernity.

And like many of us sees that the planet won’t sustain this pattern. Life is complex, and pattern bound. Awareness isn’t complex nor patterned.

It's hard to get very excited about stuff that might happen long after I'm dead. I think your optimism has no foundation but we can, of course, wish for anything, and those wishes can become extreme for timescales that stretch out long past our demise.

Humans didn't actually do anything wrong. Without free will, humans are just following the neuron sequences that have evolved over millions of years. If you regard that natural behaviour as a mistake, then, yes, humans, if they remain a species, will probably repeat those mistakes, once the dust of this civilisation has settled.

Brilliant, Dr Murphy, as always. It is heartbreaking to experience the denial when speaking with friends and family who should have more wisdom. I, as well, think a future that has the remnants of human population may find a much more meaningful existence than what we find ourselves in now. Perhaps I am prejudiced as one who has a temperament for the visceral in life instead of the “bells and whistles” of modernity. Fully on board with Wes Jackson and Wendell Berry as the “smart” ones.

Hey, Tom…

I probably sound like a broken record, at this point, but I feel compelled to mention Ernest Becker once again. When I read his book, 'The Denial of Death,' more than a decade ago, it clarified so much that had confused me. Hard to put it in a nutshell, but the behavior you describe, "Look at how well we've done. Of course we will keep doing better." This is a commitment to a "way of life," a "world view," a means to ensure oneself that the work to which one has committed one's life will guarantee that one's way of life will continue…forever! Because, if it doesn't, then all my life's work will have been wasted, and I might just as well never have lived at all! But, just look at me, at all I and my fellows have accomplished, at the wonderfulness of my mind that can project itself into an endless future, into the vastness of space, into the quantum nature of everything…surely this proves that my way of being in the world will never disappear. Your petty challenges to my superior cognitive/logical intelligence are beneath me. And while it is true that, one day, my body will cease to function (although we are working on that one), and my mind will disappear from existence (until we can figure out how to transfer it into an immortal biological computer), despite all that, the Work! that I have Accomplished! will be Remembered! by all those who come after me, and I will be IMMORTALIZED in the collective memory of my race!!!!!

That kind of thing is hard to give up.

I actually started the Becker book but failed to stick with it. The prevalent "hero" theme was not resonating. I don't doubt I'm missing out on great insights, so at some point I'll probably give it another go.

There is now a movie, “All Illusions Must Be Broken” where you can hear Dr Becker’s voice, including on his death bed.

It is no waste of time to watch this one. 🙂

That "hero" thing… The essential thing that makes a hero is the willingness to give up one's own life to save another's. Perhaps the most essential thing we must face as civilization falls, is that we will all have to be heros.

@Gordon Shephard

Indeed.

Oblivion waites for all of us.

Long time reader, first post! No doubt the proponents of human

ingenuity often have a background in economics or are technological

ueber-optimists? Whenever I express doubt about our ability to

innovate ourselves out of our mess, I am told by said proponents to

reflect on our amazing progress and how it surely will extend forward,

and that I could be wrong about my misgivings (so can you, I think to

myself). Being a natural scientist myself, I find it hard to

understand the economists faith in innovation as a driver of perpetual

economic growth.

I recently read a blog post by Economy prize winner Paul Romer on The

deep structure of economic growth, in which he claims that

"non-economists have said that it helped them understand why unlimited

growth is possible in a world with finite resources". Innovations can

multiply indefinitely, much like cookbook recipes in a kitchen,

allowing endless combinations of ingredients. One would think though

that the recipes would be useless if the refrigerator is empty, but

apparently I am missing the bigger picture here.

I do have one question regarding your comments on recycling. Bob Ayers

has written a lot on recycling (e.g., The second law, the fourth law,

recycling and limits to growth) in which he shows that infinite

recycling is not thermodynamically impossible, provided you have a

sustained energy source and a large enough waste bin from which to

mine. I'm sure you are aware of it, but I don't know if you have

commented (if you indeed have, sorry if I missed it, I haven't read

everything you've written 🙂 ).

Thanks a lot for you thoughtful posts, I enjoy reading them a lot.

I assume you meant, " in which he shows that infinite

recycling is not thermodynamicall possible" rather than "impossible." But if such a possibility requires "a sustained energy source and a large enough waste bin from which to mine" then it really becomes impossible.

I am not aware of Ayers' work. I also find have little tolerance for armchair theoretical capabilities. Theoretically, thermal power plants should be able to achieve 80% efficiency, but in practice it's half that. Post-distribution recovery of manufactured materials is itself a practical limitation that will stymie theory dreams. I won't bother to look it up myself, but I would lay money on the supposition that Ayers has never engineered anything.

Finding a metaphor to fully describe our predicament is tricky.

How about an avalanche?

Starting small and picking up material as it goes until the whole cascading mass comes to an abrupt end at the bottom of the valley.

(An abrupt end being my prediction of the future of modernity. I can't see things unwinding over a long period of time, in the mirror image of modernity's "rise")

Most graphs show the measures of modernity "rising", so the avalanche metaphor, is perhaps wrong.

Or modernity has always been on a downward slope, but we have never looked at it like that.

Growth always seems to be imagined as going upwards. (In my head anyway) But why not downwards?

Yep, good article.

"….yet can’t reconcile how someone so smart misses the big-picture perspectives that grab my attention."

That's easy, the vast majority do not see the world through an ecological lens. Once you do, the implications are clear, enormous, and liberating. You don't have to be a trained ecologist, just learn a slightly different way of thinking.

The vast majority will not countenance anything that threatens their perceived privilege, whatever their status may be in the social pecking order, and will fight like hell to maintain that privilege:

John Kenneth Galbraith:

“People of privilege will always risk their complete destruction rather than surrender any material portion of their privilege.”

The golfball/rock will indeed come to rest. When the human population has declined to whatever the new sustainable carrying capacity is. It was c35 million before modernity:

http://paulchefurka.ca/Sustainability.html

(not sorry if I've posted this before, I do think it's important)

by any logical extrapolation of ecological overshoot, it will be less than that, if not zero.

"Biologists are pretty clear that a sixth mass extinction is underway as a direct result of modernity."

I would say, rather than underway, the 6th mass extinction is near the end point. The 70% decline you mention in our lifetimes is only measured on a 1970 baseline; if it was measured on a 1750 baseline, or 12000BC baseline, it would be nearer 99%.

Lyle Lewis has some thoughts on this, I've just got round to ordering his book:

https://race2extinct.com/

The 6th mass extinction is not just because of modernity, but because of humans full stop.

Scientific Briefing https://xkcd.com/2278/

Another xkcd, but this *is* related to the post imho.

Tom,

I recently finished Slouching Towards Utopia: An Economic History of the Twentieth Century by Brad Delong. It has a similar thesis that we are moving toward an era of abundance and the ability to provide a safety net for all. He acknowledges the impact on the environment but seems mainly focused on the opposition by the plutocracy to increased social democratic support structures.

We are likely entering a time of economic stagnation and a collapse of social support structures precipitating an all out assault on the ecosystem. Trump is now trying to restart shut down coal fired plants.

Much worst is ahead. With difficulty I watched a YouTube video of Musk railing against empathy. He indicated that empathy was a poison to the “West”. The hyper and super rich will strive to accumulate everything to themselves while crashing the world.

For some reason, I think that you are too cautious in estimating the time of the start of the acceleration of the collapse, the speed of the change of states and the depth of the consequences.

It is clear that all these are "scenarios", but I would give a different story:

A car (present day) inside which there is an ant, a parrot, a newt, a squirrel, a dog and a person (driving) on a section of 250 m (the time of the set of future "consequences"), begins to accelerate by pressing the pedal to "growth", in front of a concrete bumper perpendicular to the road (growth limits).

It is clear further… the trip will not end well for everyone, perhaps except for the ant and uninvited microbes and viruses (the base of life).

Forming chains of interconnectedness of many sectors of the meta-crisis, you see that the risks increase, like snow sticking to a wet stone rolling down a mountain. The mass of the ball is growing and it is not possible to control it, even trying is futile and dangerous for life. Only its collapse and disintegration will stop the danger and destruction.

Your observation that seemingly inteligent people ignore the reality of ecological overshoot is quite accurate, but unfortunately it's to be expected. If you haven't read Jeff Schmidt's "Disciplined Minds", I highly recommend it. He makes the case that the formal university and professional training institutions of modernity function as a filter; preventing people who might not fully support status quo modernity–and all it's assumptions and myths–from occupying positions of relative authority. And so according to him we should expect that educated and inteligent people are more likely to avoid facing reality than people who are less educated and less inteligent.

The idea is that the majority of white collar professionals view their positions and the institutions they are part of as being meritocratic. They got where they are today because they worked hard and applied themselves, and because the overall system is built on a just foundation (any potential issue can be addressed with piecemeal reform). Accepting the reality of ecological overshoot would mean accepting that role that professional institutions have played in normalizing overshoot. Really coming to terms with this and letting your mind stray from the ideology that allowed you to so easily acquire power/priviliedge in the first place would amount to carreer suicide.

To develop the capacity for critical thinking on a systems/governance level, it really helps when there is no immediate consequences for your own material well being as a result. Which is way i find it much easier to talk about collapse with people who didn't go to university or people who work blue collar jobs.

But you are absolutely correct that despite all this, smart and inteligent people have a moral responsiblity to seek the truth, no matter how awful/unpleasant such a process might be. It is better to be frightened by what we think is true, than to cower behind comfortable illusions that help us deny those uncomfortable truths.

100% agree.

As I see it, university diplomas have become too transactional and are perceived in the social psique to act as a vehicle to higher (and therefore safer) lands in the social pyramid. The factual knowledge that comes along undergoing higher studies has become completely secondary, and underpinning the social pyramid structure that allows those with a diploma to live relatively comfortably today in the managerial-professional class poses an existential need for most of them. It doesn't matter how well put and logical your input may be that if it contravenes the future, idealistic life perspectives (mental models of the world) of these people you are going to be ignored at best. People form their opinions on the basis of herd behaviour in most cases and seek comfort in hearing like-minded opinions. I wouldn't take the ostracism so close to my heart, at the end of the day humans are social animals looking for maximizing comfort on given available resources with minimal effort without thinking too much on the long term, feeling sure that they will be able to adapt and steer the boat. You can call that optimism, in spite of the multiple and obvious holes in the hull of the modernity vessel that was always bound to sink.

Good article and comments.

I'm reminded of sitting in an office years ago with a bank employee as he referenced a long-term stock market value wall-chart showing overall growth over decades. His logic was that any long-term investment must increase in value. I pointed out the fine print of "past values are not predictive of future performance", and he essentially waved that away. It wasn't long afterwards that I decided investing wasn't for me, and garden tools and seed-saving were a better store of wealth.

Anyone predicting the future on past performance should be reminded that they haven't died on *every single one* of the thousands of previous days. By their logic, they are then immortal. I'm sure the dinosaurs would have argued with each other that since they had been the dominant life-form for millions of years, there's no way that could ever change. Things are the same, until they aren't…

Entropy—its irrevocable nature, and the fact that it can only increase in a closed system—has proven to be the key concept in my discussions with educated people.

Once people grasp the implication of the Second Law—that all energy consumption must irreversibly increase total pollution—a door seems to open. They realize that the faster we consume energy (regardless of the immediate source of the energy), the faster we pollute. And they perceive "time's arrow," the ratchet effect, the irreversibility, of the changes caused by energy consumption.

Sometimes I have to give examples to explain the Second Law (air flowing from a punctured tire, heat moving from a stove to a room (and never in the other direction), aging, etc.) Sometimes discussing collapse of the natural world (loss of half of all wildlife in the last 50 years, loss of 40% of phytoplankton, recent extinction of the vaquita and other species, etc.) is helpful. But once they "get" the Second Law, the end to which modernity is driving becomes clear.

Perhaps I have been lucky in my discussions. But I've yet to encounter an educated person who, having grasped the Second Law, did not perceive the problem of modernity.

There needs to be a Second Law of Wealth corresponding to the Second Law of Thermodynamics/Energy.

Wealth is supposed to represent energy, but behaves exactly the opposite way in the second law sense: It always flows from the less wealthy to the more wealthy.

The First Law of Wealth corresponds to the First Law of Energy, if it is admitted that the economy, despite protestations to the contrary, is really a zero sum game. For some people to be wealthy, other people have to be poor.

I don't think I could pull off an entropy-based argument without making stuff up. Since the "closed system" is the universe, including the sun, entropy can experience local reductions as long as the books balance overall. Just as ice cubes can be made (even in nature!) as long as the overall "room" entropy increases, lots of amazing negative-entropy processes can happen on Earth as the sun spews photons and particles into the void (driving total entropy way up).

I guess my argument of modernity running out of non-renewable resources has a tenuous connection to entropy, but not in a strict thermodynamic sense (thus can't really invoke the almighty authority of the 2nd Law without being on shaky ground). See my 2013 post called Elusive Entropy for more. Basically, as a physicist, I wouldn't dare go there.

Persuasive power of the entropy argument derives from its break with the mechanistic (and, therefore, time-reversible) nature of Newtonian physics (Georgescu-Roegen).

Biology, chemistry, and thermo (to a large degree) break sharply in their manner of thinking from physics … And it is the perception of this break in thinking (especially about the nature of time) that allows the entropy argument to be persuasive.

In physics, we're taught to think of the flight path of the ball as a time-reversible arc—the path is the same going "forward" as it is going "backward."

Biology, chemistry, and thermo are different. Natural processes as "irrevocable." The explosion cannot be reversed. Humpty Dumpty cannot be reassembled without creating more pollution. Time's arrow cannot be reversed (Eddington, Gibbs). So the local reduction of entropy at Point A (by some construction of modernity) creates, in practice, an *irreversible* increase in local entropy at Point B (a mine, a former habitat, ground or surface water, etc.)

The entropy argument, as conceived here, need not postulate anything more than that there is no unalloyed good in nature; that all things in nature are conversions, trade-offs.

It's this notion of an irrevocable trade-off inherent in all constructions of modernity that, I think, once grasped, proves persuasive to the educated.

(You'll find that Georgescu-Roegen and his students provide a thoughtful critique of the mode of thinking about time that's inherent in classical physics.)

Yes to everything you say about irreversibility and the arrow of time being related to entropy. Most videos shown in reverse are obviously reversed, which brings home the ubiquitousness of this feature of nature. Entropy is a fine argument for why modernity would not continue for tens of billions of years. But to invoke it, or the second law of thermodynamics to argue that modernity's gig will be up on century or millennium timescales strikes me as pretty dubious. For instance, entropy limits the efficiency with we could use solar energy to 95%. That's so far above any practical limit that it's not relevant. So, I don't think I could pull off any entropy-based argument with an entropy-savvy techno-optimist about modernity's likely demise/decline in the near term. Other practical arguments come to bear.

[edit: shortened considerably]

I’m curious if you have any particular rationale for suggesting that ocean acidification may be worse than climate change? I’m not personally sure which is worse but see them as extremely interconnected problems as they are both products of same CO2 pollution.

My instinct is not to downplay climate change but to up-play it, using it as a familiar ‘hook’ that people have already been exposed to while introducing them to the broader polycrisis while pointing out that the mainstream actually downplays climate change’s severity.

The Tolkein-esque way I play it in my head has Frodo on Weathertop with his short-sword Sting, climate change is the Witch-King of Angmar (wouldn’t want to mess with him), but there’s 9 ringwraiths all converging simultaneously with their swords drawn (ocean acidification, deoxygenation, the sixth mass-extinction, biogeochemical flow disruption, land degradation, fresh-water depletion, emerging & exponential tech, energy & material descent, climate change), there’s also some big orcs like deforestation, overfishing, geopolitical chaos, 9-nuclear weapon states engaged in a Mexican standoff, while Sauron is perhaps ecological overshoot. I’m not sure exactly which sword is going to enter Frodo’s (modernity’s) belly first, but ultimately, all of them will, and the poor little guy isn’t going to make it…

"I’m curious if you have any particular rationale for suggesting that ocean acidification may be worse than climate change? "

That jumped out at me too, briefly, but then I remembered.

Something like 68% of our oxygen comes from the ocean phytoplankton. Trees make up the bulk of the rest.

That same phytoplankton has seen a 40% decline since some date stamp I can't remember. Ocean acidification, stratificiaton and heating are the prime drivers of the loss. Although no doubt pollution is adding in ways we don't know yet.

12,000 years ago there were 5 million(-ish) humans and 6 trillion trees by modern calculations. Now there are only 3 trillion trees and 8 billion humans. If climate change didn't do us in, lack of oxygen would eventually.

I think that this is a fairly common misconception. I would suggest reading the paper ‘Impacts of Changes in Atmospheric O2 on Human Physiology. Is There a Basis for Concern?’ by Ralph Keeling and team. Basically, there is a vast store of atmospheric oxygen that was gradually accrued over hundreds of millions of years, starting about 2.7 billion years ago, and it is not modified contemporaneously very much by photosynthesis. Due to other processes like respiration and death and decay of organisms, most of the oxygen produced by these organisms is also consumed by them. A quote from the paper: “even if all photosynthesis were to cease while the decomposition continued, eventually oxidizing all tissues in vegetation and soils, including permafrost, this would consume 435 Pmol, equivalent to a 1.9 mm Hg (1.2%) drop in

P′O2 at sea level. Although land and marine biota can impact O2 at small detectable levels, they are not the “lungs of the planet” in the sense of ensuring global O2 supply.” There is some atmospheric oxygen depletion happening now, mainly due to the burning of fossil fuels, but relative to the vast atmospheric oxygen supply, this turns out to be fairly nominal.

Oxygen depletion is a concern when it comes to the loss of dissolved oxygen in the ocean and in lakes however. There are two major mechanisms, first there is the ‘a cold beer is fizzier than a warm beer effect’ in that cold water can hang on to more dissolved gasses than warm water per physics, thus these bodies of water reaching record hot temperatures contributes to aquatic hypoxia. Secondly, agricultural runoff of phosphorus and nitrogen pollution support toxic algae blooms that spawn oxygen-eating bacteria that cause anoxic aquatic ‘dead zones’. The ocean has lost 2% of its dissolved oxygen since the 1950s (the situation with lakes is much worse), and this is definitely a concern.

Loss of phytoplankton is a serious concern and would be a disaster for the biosphere because they are the base of the marine food-web, so their absence would cause cascading extinctions all the way up the trophic pyramid. There have been concerning observations such as a 65% loss of phytoplankton productivity in the Gulf of Maine in the last couple of decades, while there was another study tracking diatoms where declines greater than 1% per year were observed. As for ocean acidification, it would impact coccolithophores especially badly since they have calcium carbonate plates/scales/shells as part of their physical structures.

First, let me say that I could be wrong. If I list the threats we hear about from climate change: sea level rise; higher temperatures; more extreme weather,; fires—and compare this to a moratorium on shell production in the ocean, I think the latter is far more devastating. Crabs, corals, shrimp, snails, clams, and countless others would quickly go extinct.

How ecologically devastating is it if Miami is flooded over a century, for instance? Temperature and storms might well add up to big ecological disruptions (certainly economic mayhem), but maybe not at mass-extinction proportions. Getting rid of calcification in the ocean seems almost sure to cause a marine mass extinction (eliminating a MAJOR trophic component), which I think ripples to the land as well (richly interconnected in ways we can't fully appreciate).

So, of all the problems caused by CO2, I put ocean acidification as more devastating (and fast-acting) than the climate change effects. As I said, I could be wrong, but this is my rationale.

Given CO2 levels (and temps) have been much higher in the past, which presumably means ocean acidity was much higher during those periods, does that imply that plankton can adjust to higher ocean acidity if given enough time to evolve with a gradual increase, rather than the breakneck speed we are forcing upon them now? Or is there a threshold at which it is simply not possible for shelled plankton to exist and other types of oxygen-producing marine life take over?

A few years back, 11 billion snow crabs died off the coast of Alaska due to a marine heatwave. The mechanism of their death wasn’t because temperatures exceeded what they could survive physiologically, but because the heatwave disrupted the trophic web while simultaneously cranking up the crabs’ metabolisms, putting them in a situation where they needed more calories while there were less calories than ever to be had. – Causing them to starve death en-masse. There was a similar situation where a heatwave caused a mass casualty event of common murres in Alaska, more than half of them died off in what has been described as the largest mass-casualty event of any single bird species in recorded history. Hot temperatures cause birds to pant, increasing their metabolisms, while the trophic disruptions create a temporary ecological overshoot situation with permanent disastrous consequences; the birds starved. The scale of the devastation was something like 16x the casualties created by the Exxon-Valdez oil spill, it happened on American soil, but ask your average American on the street and I’ll bet they’ve never heard about it. In any case, this metabolic requirement increase, trophic disruption, and mass-starvation pattern is very concerning.

2023 averaged 1.48C above pre-industrial, 2024 1.6C, while 2025 is tracking at 1.65C so far despite La Nina. A 1.57C average into the Holocene 13.8C pre-industrial baseline yields a 11.4% increase. Ocean pH has changed from 8.2 to 8.1, but because of logarithmic nature of pH scale, this represents ~26% increase in acidity, so I guess I’ll take your argument that ocean acidification is occurring at faster relative velocity than climate. Honestly, I have been somewhat surprised at the Potsdam Institute’s assessment shows climate forcing deep in the red zone while ocean acidification has yet to cross into the unsafe operating space, while there are plenty of ocean scientists that would argue otherwise.

The major impending climate risks as I see them are the positive earth-system feedbacks such as permafrost melt, methane hydrate melt, ice melt resulting in earth-dimming albedo changes, and worrying signs shaping up with cloud formation changes which all threaten to unlock further accelerations. Another factor that I don’t see being contemplated much, especially among the IPCC crowd, is the termination shock effect. Per Hansen’s work, our industrial pollution aerosols are reducing the felt-effects of climate forcing by ~20%. Thus, should there be a precipitous drop in human population and corresponding industrial activity, such as from hitting the plague-side of overshoot, earth’s weather system would wash the polluting aerosols out of the troposphere in fairly short order, within a year or so, resulting in a pretty substantial heat-boost, shocking the system. I am personally more concerned about the impact to the biosphere than whether Miami is underwater.

Another great article. However, ideas along the lines of "a stable community of life" keep cropping up in your writings, as though there were some configuration of ecosystem that would last for ever (and be a wonderful place).

Ecosystems eventually reach an apparently stable configuration, a climax state. But this is inevitably temporary (or else, the first ever ecosystem that reached a climax state, would still be around today, and we wouldn't be).

I'm not sure what a normal way of life would be. All organisms (grouped by the vague term "species") are behaving in exactly the way that they evolved to. And evolution cares nothing about what that is, though it may have something to say about how long some behaviours must last.

Don't put timescales in my mouth. Of course stasis is not in the cards. I consider what has happened on Earth in the last few centuries and millennia to be off-scale-anomalous compared to how life went for timescales many thousands of times longer. Stable is thus a relative term, and not a rigid concept of timeless, changeless fantasy.

Sorry about that. It seems we agree.

Once modernity ends, I think all remaining humans will figure out that life is a struggle. Undoubtedly, there will be moments of joy and satisfaction but it will be a tough slog for much of the time. This is why I'm not too anxious for modernity to end though part of me wants it to. I suspect I won't have to deal with it, but you never know.

Dr. Murphy, are you familiar with this? Is this about right?

https://xkcd.com/1732/

In a skim, I didn't see any alarm bells. It conveys the unusual stability of the Holocene rather well.

I think most people are just so unaware of their normalcy bias that it's bordering on impossible for them to see anything else. When they go to the gas station or supermarket, there is always gas and food. Always. Even during the height of the COVID lockdowns there was adequate food. That these systems could fail is beyond the pale, for them even to decline seems unlikely. It's hard to 'see' the interdependence of our systems without it actually happening. And also, many of our 'visible' systems can be manipulated so that they seem resilient (stock market (debt supported), renewables (fossil fuel supported), etc.).

But the way many of my peers would start to 'see' it would be via an extended flattening or dropping growth in growth. In my business, the expectation is for 3%-7% growth year-over-year. An occasional downturn can be tolerated, but if we had 5-10 years of zero growth or, god forbid, single-digit drops in growth, I literally have no idea how they would react. If it happened across the board for all businesses, there would be chaos. Not sure if I'll ever see it but I won't be surprised if that's the beginning.

My guess is that population decline will force economic contraction, as well as failure of social safety net systems (dependent on growing young workforce plus growth in economic scale). Japan and a few other affluent countries are already declining, but currently surviving economically on the back of exports to affluent countries. When these countries, too, turn over in the next decade or so, no life rafts will remain to save growth. Africa—the only region still growing population—probably won't suddenly become the prosperous customer, and it also probably can't continue growth when substantial food imports are disrupted by economic collapse in the affluent countries that currently supply its caloric fuel. Depending on whether you've got a couple decades left, you may or may not see this begin to manifest.

Another metaphor that I like, and which seems to leave most people nodding in agreement, is the baseball. When a batter hits a pop-fly into the air, how does the outfielder know where to run in order to catch the ball? It's not a prediction, the outfielder is not calculating the physics of it, but anyone can see the trajectory of the ball.

So too with the trajectory of industrial civilization, as originally described by the Limits to Growth report some 50 years ago now.

Could something unexpected happen? Sure, the ball could hit a bird, or a giant gust of wind could blow the ball out of the stadium. Not likely, as any fan of the game can tell you.

Collapse deniers! That's the phrase I was looking for. I had this very same discussion with someone last week. They were talking, with an air of superiority, about climate deniers (not paid deniers, just general working class public) with regard to electric cars and heat pumps. I put it to them that they were also a denier, but that their denial was worse – because they had the audacity to look down on those climate deniers. The way I tried to explain it as that they made the effort to understand all the science underpinning climate change, and then just stopped. They stopped investigating, stopped trying to understand. Which is something I don't understand about collapse deniers. How do you uncover something so unfathomably catastrophic – potentially – as climate change, understand the strength of political and economic forces that try and obfuscate and downplay it, and then think "well, there can't be anything else to worry about"? I find it such a strange point at which to erect a boundary.

The only thing I can put it down to, is that they've already "solved" climate change. The electric car world will see us good for eternity. When I suggested that was a bit ridiculous because it didn't solve any of the other crises, it was suggested that we should concentrate on solving climate first because it was the most pressing. That was possibly the most stupid thing I'd heard for a while. Although I don't think that's an unusual position. I asked the obvious: what if the solution to climate change either exacerbates the problem, or has to be undone in twenty years time because you didn't think of the other crises whilst planning (both are extremely likely)? It then descended into the tech solutions space.

It is the real denial we should be speaking about.

And BEVs wouldn't even solve the climate crisis, since they, and the energy source they use, require fossil fuels, quite apart from the environmental damage they do from mining and refining of minerals.

Agreed, however that point is slightly harder to argue in its own right. In theory, you could transition to an all electric economy, with CCS for the scraps that can't be done via electric via the "renewable" sources. In theory. It's not a theory I buy into, but it could certainly be argued that it is possible, and indeed worth pursuing, if your only issue was climate change. However, the argument becomes ridiculous when you add in the many other crises face, as the article mentions. I'm genuinely flabbergasted when I hear people who are genuinely – it seems – environmentally focused.

I have had a Nissan leaf since 2011. It broke about a month ago. There is nobody in my area that can fix it, and even if they could, the cost would be several thousand GBP. I'm having to scrap it. It lasted a year longer than the average car in the UK. Some of it will be recycled, some not. What I bought into, fourteen years ago, and what governments around the world are actually trying to pursue, was the continuation of the car industry. Not sustainability, or green industry. We could pretend that it was possible to switch the 8 billion to electric cars in a one off exercise. To replace them every thirteen years, though, is just ridiculous.

Mike, you are correct. I don't understand the push for electric privately-owned vehicles as a panacea. First, there are the issues you listed. Next, there is the problem of electricity itself. There is very little introspection about how to generate it without fossil fuels (or nuclear). Brian earlier in the comments put it well: "renewables (fossil fuel supported)".

I used 'privately-owned' as an adjective, because I've often thought about requiring everyone to travel by electric buses and trains. Can you imagine the upset that would cause?! Yet even that would not make a dent in the resource, food, and ecological apocalypse that is hovering on the horizon, as Dr. Murphy described in his post.

*I feel sympathy for Rico and his Nissan Leaf that died after 11 years. I'm still driving my mother's IC 2003 Toyota Camry, putting about 1500 miles a year on it (with no plans to change that), but I'm surrounded by new IC SUVs. This too is futile, in the larger scale of things.

What is your opinion on Ajit Varki's idea of the Mind Over Reality Transition? I think it helps explain why so many people remain in denial about our situation. There are other reasons as well, such as:

– Most of the population is not ecologically literate. I had to study this subject for several years to get a deep understanding.

– The mainstream media for the most part doesn't discuss overshoot. Sometimes they will discuss individual symptoms of overshoot such as climate change or species extinctions, but they don't put the pieces together. Even if they were aware of overshoot, they would probably lose funding or ad revenue if they talked about it openly.

– Our economic system is predicated on perpetual growth. If large numbers of people realized that growth was ending, the whole house of cards would collapse.

Your list seems to capture important pieces. Denial is certainly a powerful mental escape. I have had some exposure to the MORT premise, and find the "origin story" to be flimsy: requiring two simultaneous mutations/adaptations on the notion that awareness of one's own inevitable death (event 1) would lead to a nihilistic suppression of procreation without compensating denial (event 2). The easy hole to poke is that event 1 by itself could just as easily trigger a frantic urge to reproduce as the next-best thing to immortality: propagate your genes forever, a la Genghis Khan. So, yes to denial as an important influence, no to the simple model that fear of death is the source. Lots of stimuli might result in denial, acting in parallel and in different measures for different humans based on experiences and dispositions.

I agree. MORT is an attempt at a rational answer as to why we deny reality. However, I see our denial as a feature of being a species. Our lack of free will means that we simply follow the behaviour of any species when it comes to survival and reproduction – it's done without thinking about a far future that is impossible to predict.

I was going to paraphrase John McCarthy's 'Progress and its sustainability' [1] and say that available energy (solar insolation) is abundant and with this abundance of energy all problems can be tackled.

However, it is hard to recover from your knock-out punch:

> "But most concerning to me is what we already do with energy. Answer: initiate a sixth mass extinction by running a resource-hungry, human supremacist, global market economy. Most climate change “solutions” assign top priority to maintaining the destructive juggernaut at full speed—without question."

But still, let me play devil's advocate. Let us say that one of those currently unimaginable, but physics possible, energy breakthroughs is heavy fusion: Pb + n×α = U. Of course, this is endothermic, unlike light fusion, and is primarily intended as a means to store solar energy in the form of nature's ultimate battery—U235.

Heavy fusion would make available orders-of-magnitude more energy than possible with fossil fuels. Perhaps, with this much of available energy, the capitalist system will be able to pay for all of its externalities, which heretofore have been dumped on other creatures and the poor?

[1] http://www-formal.stanford.edu/jmc/progress/

John McCarthy references Bernhard Cohen on breeder reactors as the most possible energy breakthrough. I've used a still more imaginary 'heavy fusion'.

Okay: the dream of fusion and essentially unlimited energy budget… What happens if every jackass on the planet has access to abundant, cheap energy? Ecological restoration and trimming the scale of our impact down by several orders-of-magnitude, or a free-for-all of exuberant expansion and exploitation of what's left of the natural world. Which adult will say no and get away with it? It needs to do more than "work" in our heads. Imagining and executing are ridiculously far apart.

Addendum: "Yes, officer, I know I have a abominable track record of destruction and armed rampage. But if you just gave me the ultimate weapon, I'd suddenly be a different person and stop committing all these heinous acts. Really: can't I have it please? I'll be so good. Trust me." It's not the technology, but the intent that matters.

Agreed..

Abundant, cheap energy is the last thing we, or the rest of the planet, needs!!!

@tmurphy,

I guess you are right that energy, like fructose, is an addictive substance. Having survived for eons in an environment of scarcity of fructose/energy/other-dopamine-producing-experiences, humans have not evolved a self-limiting control mechanism, when faced with abundance of these, and do tend to go overboard.

But, it must also be remembered that there are enough competent engineers with "disciplined minds" or brainwashed in the ideology of 'perpetual progress is sustainable and absolutely necessary'. So, if light fusion, heavy fusion or effective breeder reactors are technically possible, they will be created. You or me voluntarily refraining from working on these technologies will make no difference. To paraphrase Jeff Goldblum's character in Jurassic Park: "Capitalism finds a way!"

What I'm genuinely curious about is what Klein, and those like him, really think behind the scenes – is there any internal wrestling going on? I don't disagree with the other comments that a person won't see something if his well-being depends on not seeing it, and granted, between writing a book about a glorious Abundant future and including a book about how to restart industrial civilization should it collapse on his 2024 "must-read" list, it would seem obvious, but then again, there's a lot of money in hawking hope. You found the Klein interview because he's "promoting" (trying to sell more copies of) a book, yet another one in the lengthy canon of same old story, which I expect we'll see more of as reality continues to erode that fiction. I'm starting to suspect the only ones we can trust to tell the truth about overshoot are the retired – Daniel Quinn, you, Wes Jackson/Bob Jensen (I just finished their "An Inconvenient Apolcalypse".), etc.

I would concur that it's about individual psychology more than intelligence or smarts, and one's investment in the current way of things. How in love with modernity is the person? Or, in other words, how attached are they to a vision of their individual future where modernity has finally fulfilled its end of the deal? I chewed on the idea of it being more to do with success or class, but I work a menial job and have plenty of co-workers who still believe there's a pot of gold at the end of the rainbow for them, despite all evidence to the contrary – and since most won't get the things or life they're chasing anyways, they'll still be able to hang on to that hope and run run run on the high-speed hamster wheel, whereas the well-to-do customers we serve…. well, I imagine there's occasional misgivings, but books like Klein's will keep nipping those in the bud!

We're so pumped full of that relentless, blind positivity that it's hard to turn it off, for most people – I feel like I've been hearing crap like "the sky's the limit" and "if you dream it, you can achieve it" since I emerged from the womb, ecosystem be damned! It always struck me as a trap, or an expectation full of pressure, not a path to freedom and happiness, but this view left me as a minority of one for much of my life, and the recipient of many unkind comments and disdain for the fact that I was not a striver. I was also "bad at the game", so up til this point it's easy for people I know to write me off as the "craving end times" type since I'm a failure by modernity's standards. Putting aside the fact that I've actually had a pretty *good* time by comparison to many of them, and maybe I was anticipating a collapse a wee bit soon and perhaps should have saved a little for retirement: who is going to be better off psychologically in a future of increasing scarcity: someone who adapts and adjusts their life to the available resources, who can be happy with what they have, or the aspirational type who decides as a youth how their life is going to look, and then forces that reality into existence in any way possible? Which one would you want as part of your circle? Whose book are you going to trust?

I think we need a new quotient to capture all this. I named it ECO-Q, the ecological awareness quotient, since IQ or EQ or any of those other ones will decrease in relevance by comparison, eventually, and all the past and current stories of material glories to come will hopefully be judged as harshly as they should be by the high ECO-Q folks of the future. Sure, we may be unpopular now, but that's because we're trendsetters! Soon all the kids will be on Team Life. Hey, I can dream, right?

P.S. I just listened to your interview on Crazy Town's 100th episode. Really enjoyed hearing more about your journey! and laughing about brain farts.

Here is a nice comic about overshoot by Stuart McMillan.

https://www.stuartmcmillen.com/comic/st-matthew-island

Excellent that he likens Earth to the island at the end (shameless contextual pun tucked in there…)

As I see it, certain things really just boil down to common sense and simple arithmetic. When you keep consuming a finite stock of non-renewable (and non-substitutable!) resources like fossil fuels, at some point the chocolates will all be eaten up and none will be left. And consuming them at an exponential rate would lead to them being finished way faster than we realize. Actually we won't exhaust the box of chocolates, but that's not because there's an infinite supply of them. No, it's because we'd need to put in so much in order to access the remaining chocolates that accessing them would be no compensation. None of this is 'rocket science'. So I don't care how many PhDs someone might have or how widely acclaimed as some intellectual giant s/he may be ; if s/he fails to acknowledge the above, then while I would maintain a facade of polite civility in front of him/her, at the back of my head I'd view him/her as an idiot, period.

The *ONLY* way modernity can continue indefinitely would be for Mother Nature to rewrite the Laws of Thermodynamics so we can actually reverse entropy and recycle energy itself. Well, maybe human ingenuity can bring it about (shrugs) — I'll believe it when I see it. But something tells me I shouldn't be holding my breath at the prospect of this.

"Damn. Blistering. How can one get up from that knockout? And the thing is, it’s a completely valid bit of logic"

Is it though ? It's more the simplistic gravity denial argument, "I have jumped off the top of the Empire State Building, I'm currently passing the 15th floor and can report all is well, just a stiff breeze, I'm not sure what all the worry was about!"

Even in the investment world there's always a qualifier that "past perfomemace is not indicative of future returns".

That aside i run into this rebuttal often on Mastodon, most wags just say you've "been banging on about this for over a decade and it hasn't come to pass". I can barley stop myself from referencing Cipolla's Laws of Stupidity as a rebuttal to thier point but instead leave it be 🙂

Professor Murphy, I too read about Abundance, but, in my case, in a New Yorker article entitled, "The politics of more."

The book sounded interesting enough for me to order a copy. (It will be delivered March 24. ) I felt the same way several years ago when you offered your book, except it was free, and I only wish to comment about the irony of receiving truth for free and having to pay for false hoods.

The New Yorker article begins with he premise that stagnation reigns in liberal New York while innovation is the norm in Texas ( and elsewhere like China). Your premise is that ultra- smart people are blind to the possibility of the growth- prosperity graph dropping off a cliff ( collapse). When I think to say that stagnation and blindness is the same thing. I only alleged that the opposite must be true as well. I.e. those that are not stagnated or blind are delusional. Thus there is a small subset of us (not abundant) who are not smart enough yet too clear headed to be in any leadership– oh yeah– and we are working for free!

"I think you can see why I’m not swayed by the tidy and fully-decontextualized lazy logic of extrapolation offered by some of the smartest people."

Once again on the climate narrative CO2 would contribute to the temperature increase. The difference between the science of the Middle Ages and modern science is that modern science delivers reproducible results. I know of neither an experiment or a empirical evidence for this assertion. The protective claim of statistical evidence implies that the stork brings the children. In the mid/late 60s of the last century, when the birth rates declined, ornithologists noticed a decline in the rattling stork population, and since it has always been rumored that the rattling stork brings the children it must be so, or when it thunders the good Lord scolds.

Tom

Thanks for your book – very informative. And agree with your views on “Abundance”.

Have you ever thought that the decline we are facing is a stark reflection of the rapacious nature of plutocratic systems and the learnt disciplining of the next levels down in the hierarchy to further their own interests by pursuing those of the levels above. Vide an ongoing genocide in Gaza which the West (both governments and media) are supporting, and few in the professional managerial class want to develop an informed opinion on.

If we can ignore an acute live-streamed genocide of a people, is there much hope for us to do anything to stem a more ‘chronic’ decline (in individual timescales) that you have charted. Perhaps the latter is an inevitable corollary of the former – that what we sow, we reap.

(all very simplified)

A cancer starts when some cells decide to stop listening the language of the rest of the body, uses it's own and begins a crazy growing existence.

Growth seems to be the only mission for these cells and they will create new blood vessels, new logistics to have enough energy to grow more and more.

The rest of the body is useful only to extract resources for this growth.

Why people avoid the cancer analogy? Is it because of the narcissism?

If you've seen my Metastatic Modernity series, you'll know that I personally like the analogy. In the 14th installment of that series I do point out some flaws in the comparison. But on the whole, it seems rather apt.

Great post. Like you and previous commentators, I have often wondered at the seeming obliviousness of various eminent personalities to the current ecocide and the likely imminence of "collapse". I've not followed E. Klein or Mr Thompson closely, but I had a brief listen a joint interview and got the gist (and, in a narrow context, they may have a point about the navel-gazing of the "left"). As to the serious issue, as non-scientists, their widely shared views of the "progress" and the future are unsurprising. What mystifies me somewhat more are the attitudes of thoughtful and well-respected scientists (esp. physicists), far cleverer than I (who can barely cope with a differential equation!) These podcasters and the great majority of their guests, many Nobel laureates among them, while not climate (or eco) deniers or Elonian fantasists, and not generally denying the possibility of collapse, still talk in terms which imply the ongoing march of technological civilisation: for instance, in envisaging their research programs extending out into the future over decades if not centuries, with new generations of particle accelerators, lunar observatories, ever more powerful AI, quantum computers etc.

One can, of course, understand the reluctance to countenance doomerism from a purely self-interested perspective: it's unlikely to be a pathway to tenured positions, grant allocations or even widespread public acclamation. Optimism bias and faith in progress (allowing for occasional hiccups) are so ubiquitous and deeply ingrained that the possession of a high IQ doesn't appear by itself to be an antidote.

Perhaps, at a deeper level, the situation relates to our species' loss of body hair and simultaneous hypertrophy of the linguistic areas of our cerebral cortices, so that we have replaced the social grooming of our primate cousins with its verbal equivalent. We confuse ourselves, because we focus on the information content of our utterances to the exclusion of the other benefits of grooming (bonding, stress release, status maintenance). Of course, the informational and other aspects of our verbal behaviour are normally completely enmeshed and it's easy to be seduced by the notion that rational discussion is taking place, rather than something more akin to a lullaby…in this case, the lullaby of progress. (There are obviously lullabies of collapse, catastrophy, etc., but these are much less soothing to most of us.)

Excellent comments. In my experience, even searingly bright and clever people don't necessarily expand their contextual cosmology to even contemplate the viability of modernity's continuance. To be fair, nothing about their existence or lives demand they do so. In fact, it can be damaging to "go there." Meanwhile, the playground beckons, and a clever individual finds no shortage of amusement and demand for their prodigious talent. Why spoil the party?