As a nod to human supremacy, any time we hear the word “population,” it generally goes without saying that we mean human population, of course. Other such words include health, lifetime, prosperity, intelligence, wisdom, murder, pro-life, culture. To many in modernity, it makes no sense to discuss the murder of an animal, the wisdom in mushrooms, or a culture among crows. Such self-centered arrogance!

As a nod to human supremacy, any time we hear the word “population,” it generally goes without saying that we mean human population, of course. Other such words include health, lifetime, prosperity, intelligence, wisdom, murder, pro-life, culture. To many in modernity, it makes no sense to discuss the murder of an animal, the wisdom in mushrooms, or a culture among crows. Such self-centered arrogance!

But where was I? Oh my—I got derailed before even starting. This post is about population of the human sort. In the 1960s, the rate of growth of human population appeared to be on a runaway ascent, enabled by the fossil-fueled Green Revolution. This alarming phenomenon prompted Paul Ehrlich to write The Population Bomb in 1968, warning of the inherent downsides in such an uncontrolled explosion of humans. But interestingly, the word “bomb” can also describe a dramatic failure, or falling flat—as in bombing a test.

In the past, my attention to population has been limited to the following points.

- The growth rate is grossly unsustainable, has accelerated historically, and is a reflection of temporary fossil fuels (Section 3.1 of my textbook).

- Despite lower birth rates, population growth in prosperous countries constitutes the largest population-growth-related resource burden on the planet (not poor countries).

- The demographic transition that worked in a past age for today’s “developed” countries is not really an option for the rest in a thoroughly-exploited world. Also, the inevitable population surge and resource demand accompanying the transition is an ecological double-whammy that Earth is not obligated to (and cannot) support.

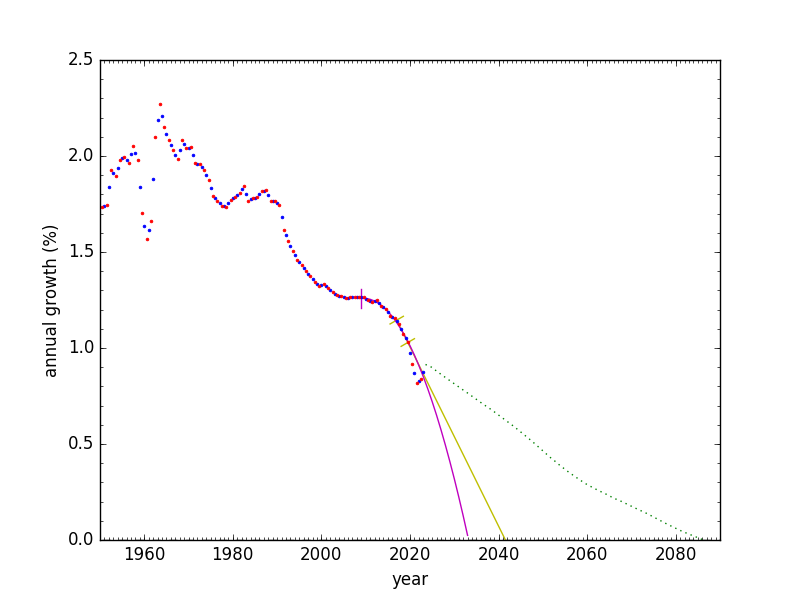

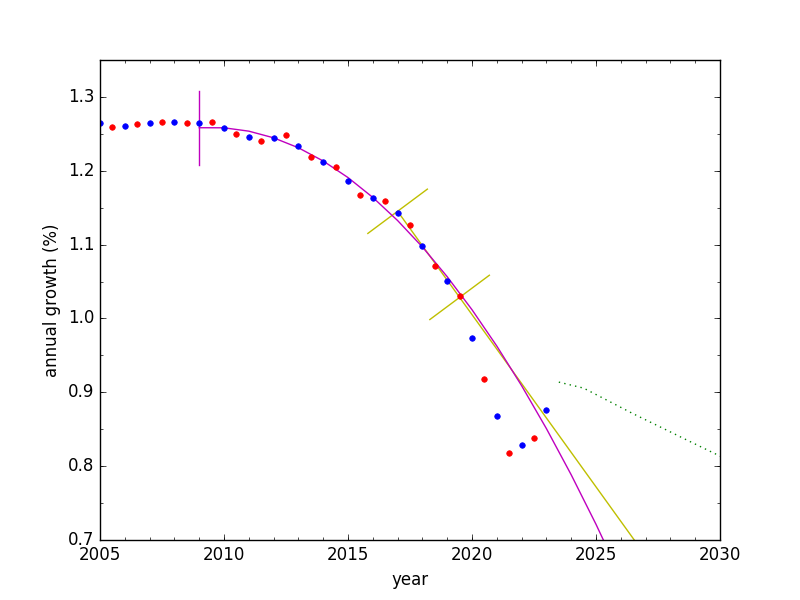

These views are still valid for me, with an asterisk on the first point that will be the focus of this post. Last week’s post included a plot of human population growth over time. I was struck by the recent phenomenon of rapidly declining growth rates, which I had noticed in tables (pre-COVID) but had never seen in visual form. Here is the relevant graph in a larger format, straight from the United Nations’ 2022 population report and associated data.

Data (dots) and projection (green-dotted line) from the United Nations. We’ll get to the solid curves later.

The annual fractional increase, in percent, is shown as blue or red dots, depending on whether tracking the July 1 to July 1 annual increase (blue, centered on the year boundary) or January 1 to January 1 (red, centered mid-year). The green dotted line is the U.N. 2022 projection for how growth rate evolves (look how it changed its mind on the slope!). When it hits zero, in 2086, the population peaks at 10.43 billion. Or their model tells us so. I’ll get to the magenta and yellow curves in due course.

The rapid decline in population rates in recent decades is impressive. The first plummet transpired from about 1988 to 2005, dropping from 1.8% per year to 1.25%. After a decade’s pause, the downward trend resumed, lately averaging 0.85% per year.

Since human population plays a huge role in the global meta-crisis, what do we make of these trends, and how might they shape our future?

Dumb Extrapolation

I tend to be wary of extrapolations—because they often take an unsustainable and manifestly transient trend and pretend it can go on forever, even though it is unlike anything that came before and is in no way proven as a long-term normal. Obviously, shorter extrapolations are safer than longer ones. Since I spend probably too much time wondering what happens millennia from now (for which extrapolations are nonsense), it is a luxury to now think in terms of years and decades, where recent trends are more likely to hold. Extrapolation misgivings aside, what happens if we project the tail end of the decline in population growth rate?

First, we must discuss the recent impact of COVID, beginning in the first half of 2020. Looking carefully, the blue point at the year 2020 involves data spanning from 2019 July 1 to 2020 July 1, which is the first data point “contaminated” by COVID. I therefore work with points before this disruption.

I fit a linear curve to the last six points in the plot above, from 2017 to 2019.5 inclusive (indicated by yellow ticks), and a quadratic fit to a longer interval from 2009 (magenta tick) to 2019.5. The linear fit indicates an intercept to zero growth as soon as 2042, and the quadratic in 2033 (zero-intercepts are visible in earlier full-scale graph). Wow—that’s fast! I had no idea this was even feasible. Granted, we probably won’t follow either curve, exactly. The decline could ease up (or speed up), but it is fascinating to recognize that the pre-COVID course was on track to deliver us to the peak of human population on planet Earth as soon as the next decade or two! Who knew?

Starting from the last blue data point (which is already close to the extrapolation curves, having recovered from the COVID dip), if we indeed followed either of these curves toward zero growth, the world would peak at 8.8 or 8.5 billion people in the linear or quadratic cases, respectively. If this came to pass, color most of us (including me) surprised to not exceed 9 or 10 billion, and to find that we’re already 95% of the way to the peak. It’s not what we’ve been led to believe.

Yeah, But Really?

To be clear, I’m not claiming that this is what’s destined to happen. But I am now persuadable that population could peak in the first half of this century. The U.N. projection acquires a discontinuous slope from the pre-COVID dynamic, which seems suspect: where does that come from? I’ll mostly resolve this mystery in a bit.

A key reason to be incredulous is that recently-reduced birth rates across the globe represent an amalgam of many factors that are somewhat baked-in and hard/slow to change. From my years of interaction with college students, I sense that a big factor is skepticism on the part of young people about the promise of the future. We’re not in 1955 anymore, when projections came up roses. Young people today worry about climate change, war (including the nuclear variety, now pleasantly back on the table), declining prosperity, rising authoritarianism, and basically a world circling the toilet. Sure, many cling to faith in technology to save us, but that faith is justifiably getting thinner and starting to feel empty and internally desperate. So: wanna have some kids? “Maybe I’ll pass.” Perhaps relatedly: as many of the younger women I know are expressing in their lives, this seems like the best time in history to be gay. But my misgivings go beyond speculation and anecdote.

A few months ago I was pointed to an article by John Michael Greer (and later a related article), who I respect as a clear and independent thinker based on some of the things I’ve seen from him (his Elegy for the Age of Space was the bomb!). Here is a two-paragraph excerpt where JMG lays out some numbers [emphasis mine].

Let’s start with the demographic realities. It requires a total fertility rate of 2.1 live births on average per woman to maintain population at any given level; this is called the replacement rate. (That .1 is needed to account for the children who die before they reach reproductive age themselves, or who never reproduce for some other reason.) In 1970 the world’s total fertility rate was well above 5 live births per woman; now, it’s right around 2.3 and is falling steadily. Africa still has a total fertility rate of 4.1, down from nearly double that in the mid-20th century and still falling; but Asia and Latin America both have fertility rates of 2.0, North America (including Mexico) is at 1.8, and Europe is down to 1.6 live births per woman.

Some of the biggest countries are surprisingly far down the curve. India, the world’s most populous nation these days, is at 2.0, below replacement rate; China, second most populous, is at a stunningly low 1.1 despite recent efforts by its government to encourage births. The United States, third most populous, is at 1.7, and Indonesia, fourth, is at 2.1. Only with the fifth, Pakistan, do you get a rate that will sustain population growth, 3.3, and only with the sixth, Nigeria, do you get the kind of fertility rate the whole world had half a century ago, 5.1. Only six countries on the planet have a higher fertility rate than Nigeria does, while 187 have a lower rate. At the very bottom is South Korea, with a 0.8 fertility rate; if that stays unchanged, it will leave each generation not much more than a third the size of the generation before it.

I can’t argue with the numbers. But wait: something feels inconsistent. If global fertility rates have come down from above 5 (we’ll call it 5.1 for convenience) to 2.3, that’s 93% of the way to the 2.1 replacement (zero-growth) figure, yet the growth rate in the same period has fallen from just over 2% to just under 1%: less than 60% of the way down. Likewise, many of these countries, like India, are still growing their populations, despite a fertility rate that’s already below-replacement. How does this square up?

The secret is inertia stemming from the demographic distribution of ages, which has been youngster-heavy for the world as a whole. This means that the number of reproductive-aged people is on the rise in many regions of the world, so that even if the fertility rate had been at replacement rate (2.1) for the last 20 years, the total population would still grow as the more-numerous youngsters move into reproductive status. Eventually it would level out, but after a generational lag.

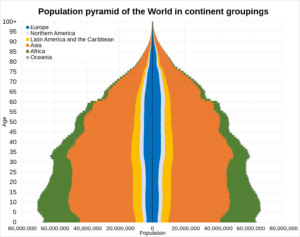

Age distributions across the world. This kind of figure is called a “population pyramid,” which tells us something about the historically “normal” bottom-heavy shape (i.e., it was very triangular several decades ago, and still is in Africa). It’s in the process of turning from a population pyramid into a “population spade” which metaphorically will dig the grave for population growth.

But a look at the global “population pyramid,” above, indicates that the bottom-heavy days are ending. Leaving out Africa, the world is already convincingly past “peak infant,” and even with Africa it’s teetering on being “demographically flat.” So: things are about to change. By the time the youngsters of today reach reproductive age, fertility rates will probably have fallen further—continuing the trend of the last decade seen in countries the world-over—resulting in a convincing population contraction. It’s essentially locked in, and a matter of waiting out the delay.

Incidentally, the downward trend in the rate data (data points in first two graphs) already folds in the dynamics of declining fertility and changing demographic realities: it’s the final result of all these real things, so that the trend reflects the aggregate effect, including demographic inertia. The “pyramid” gives us a sneak peak at what lies ahead, providing no reason to expect much in the way of a rally/surge in the coming decades.

Says Who?

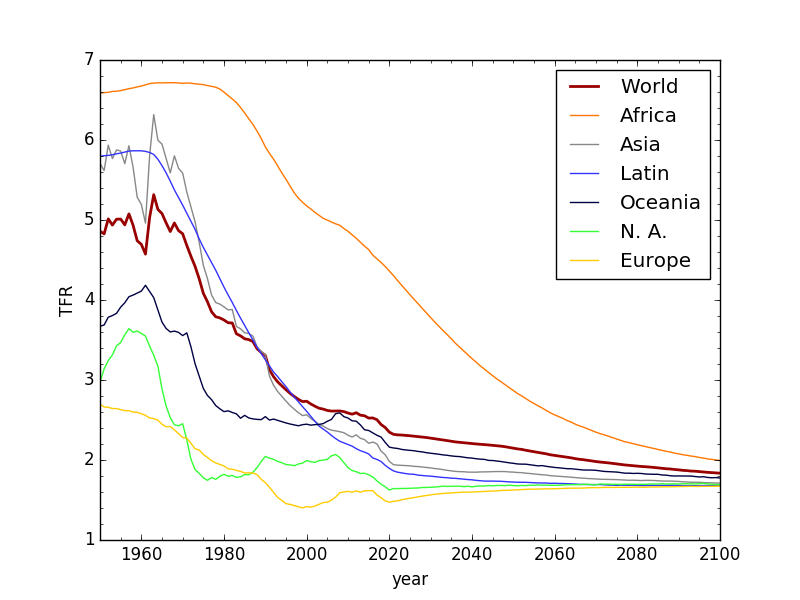

Many of the “official” projections for global population still show a lazy peak and in some cases stabilization above 10 billion people near the end of the century. I wondered how much of this is motivated by belief, so that models of future fertility rates are chosen for “sensible” and politically palatable results rather than trying to predict underlying dynamics. I initially wrote the last sentence in the present tense and then converted to past tense after looking for answers and stumbling across the following jaw-dropping graph (extracted from the 2022 UN model’s giant spreadsheet, but also here). The figure below reveals that the United Nations’ expert “model” appears to have picked an arbitrary long-term fertility rate out of who-knows-where to which all regions asymptote, abruptly abandoning their current declines to head for theory-land! I’m honestly a bit aghast.

U.N. Total Fertility Rate data (pre-2020) and projections (post-2020). Like the Nazgul who suddenly drop whatever they are doing to race to the Ring, the U.N. model forsakes recent trends to race toward a steady asymptote—around 1.7—seemingly pulled out of thin air. “Latin” includes South America, Central America, Mexico, and the Caribbean. N.A. stands for Northern America (mainly the U.S. and Canada).

I mean: look at all those artificial kinks at 2020, slapping the world out of its fairly universal (pre-COVID, note) downward trends! “We interrupt this program to bring you a special announcement from the land of wishful thinking. This station powered by fantasy.” The single-parameter “model” all boils down to this unsupportable guess at a magnificently stable and universal long-term fertility rate, leading to the green dotted curve in the first figure above. I hope you can better appreciate my skepticism now.

The U.N. model contains plenty of sophistication and granularity in projecting how each country and region evolves toward this imaginary and powerful magnet, based on a boatload of demographic specifics. But the end result really boils down to this single element of asserted imagination. It’s sort-of like painstakingly modeling the motion of all the planets in the solar system under a model where gravity is 60% as strong as it actually is: one can go to tremendous effort to incorporate every detail and interaction for every planet—but why? It’s guaranteed to be wrong based on faulty assumptions, even if otherwise perfectly executed in an almost super-human attention to detail.

They do acknowledge uncertainty in their choice and explore different scenarios that amount to varying the “universal attractor” fertility rate, but still force the world to promptly flock toward this stable happily-ever-after endpoint. Their 95% confidence intervals correspond to somehow knowing the final universal fertility rate (as if that’s even a thing) to about ±0.2, although I have perhaps no more than 10% confidence that their basic premise is right (an example of statistics conveying false confidence based on highly dubious underlying assumptions which are implicitly 100% right, somehow). I get it that predicting the future is hard, but it’s worth appreciating just how thin the U.N.’s projection is. My high-odds prediction: the real world will ignore this bit of theory and continue to exhibit unpredictable dynamics in actual fertility rates.

Other projections (like in this report) acknowledge declining fertility trends and are slightly less timid about projecting population reduction in the next several decades. I also saw a New York Times article in September 2023 expressing horror at the prospect of peak population (10 billion) late this century and the subsequent inexorable decline. The author laments the lost opportunity of humanity’s blessed ascent to greater godliness, which is classic human supremacist claptrap. I ignored most of the wailing, focusing instead on the projections, and was struck by the simplicity of models that just lock in various current “developed” fertility rates ad infinitum—resulting in an unrealistic extinguishing of humanity in a few hundred years. Sure, I was glad to see acknowledgment that the present state of affairs is not permanent, in that population would peak, decline, and bring radical change to the world. But I could not take the centuries-long single-value extrapolation results at all seriously, and dismissed the piece accordingly as it made no attempt to acknowledge changing underlying dynamics. The point of all this is that the prospect of population decline is starting to get some sporadic attention.

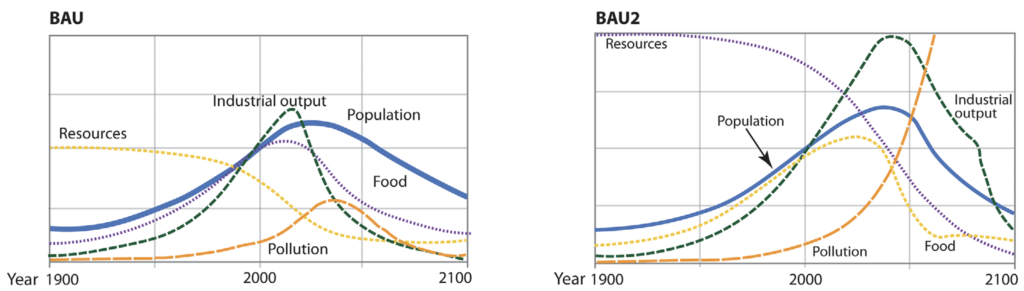

At this stage, I want to remind folks of a familiar 1972 work called The Limits to Growth, whose models almost invariably showed a population peak and decline mid-century (a bold prediction 70-plus years out that we still can’t say is wrong!). In order to coax their model into stabilized population in the face of all the inter-related factors, they had to work really hard and concoct seemingly impossible political scenarios—which is another way to say that a steady-state, non-peaking population is probably just baseless fantasy, succumbing to the ubiquitous conceit that we’re in control of our destiny and will “figure things out.” Below are two model runs from the Limits to Growth work: the default “standard” run (business as usual; BAU), and the one that doubles resources (BAU2). Both show population peaking and declining before 2050. Efforts to track progress (e.g., Herrington, 2020; see associated Resilience article) point to the BAU2 run as the one we are most closely following.

Two model runs from the Limits to Growth (from Gaya Herrington’s 2020 paper, with following attribution: Adapted from Limits to Growth: The 30-Year Update (p. 169, 173, 219, 245), by Meadows, D. H.,Meadows, D. L., and Randers, J., 2004, Chelsea Green Publishing Co. Copyright 2004 by DennisMeadows. Adapted with permission).

Also worth pointing out is a very simple model I created in a post called Finite Feeding Frenzy, based on the premise that most of the present human population is propped up by non-renewable fossil fuels that are critical for industrial-scale agriculture. As fossil fuels inevitably phase out, it should not surprise anyone to see human population follow. People in our culture resist the idea that godlike humans are subject to mundane realities like food, but what can I say: we are no more and no less than biophysical beings. In terms of net energy, a compelling argument can be made that we are already past the peak and might expect population to reflect this fact once the delay mechanism (aging to reproduction) has caught up in a few decades. Indeed, fertility rates in much of the world are already below replacement and marching down, still.

What’s Next?

Okay, so let’s say that a global depopulation trajectory manifests in the second half of this century, as I am now more inclined to believe. What does it mean? How does it interact with modernity’s fate, for instance?

As if I know!

But, let’s think about it. Do you think people will notice? Do you think it will be newsworthy? Am I kidding? It’s about people! It will be huge news and likely dominate conversations around the world for decades! Nothing like this has ever happened outside of plagues, which people probably also noticed and talked about. Depending on what narratives emerge (odds are, more than you can count), I can imagine a prevalent theme about impending decline with no end in sight. After all, infinite extrapolation is one of our favorite games. Older generations will panic that the utopia they imagined we were on track to achieve is threatened, and beseech the young to get busy. But younger folks (whose self-possessed attitudes count more when it comes to reproduction) might well see things differently, already accepting that the world envisioned by Boomers is a failure and a farce, resentfully wanting no part of it. Efforts to get them to make babies seem unlikely to be persuasive.

My Best Guess?

If I don’t like the unimaginative “theory” behind the UN model (which can be summed up as: TFR → 1.7), then what do I think is in store? I’ll take a stab without a crystal ball (although in parallel I have tooled up a reasonably sophisticated demographic projection tool so I can investigate consequences of different assumptions—maybe to be explored in a future post). I imagine that whatever has been driving the current plummet in fertility since about 2015 is not going to abruptly stop, as I don’t perceive any game-changers in the air at present that would increase fertility. I would not be surprised if the downward slope moderates, but for that matter I can also imagine scenarios in which it picks up steam. In any case, it seems rather plausible that global population could be in decline by 2050, setting off unpredictable consequences.

I’ll skip the intermediate reaction for now and zip to the farther future. I don’t imagine the present decline in fertility rate to be monotonic, which mathematically leads to near-term extinction. I think it rises again, and probably back up to the replacement neighborhood as population (approximately) stabilizes at a much lower value. What I say next will probably strike many as a disastrous outcome, but after modernity winds down we can probably expect death rates and infant mortality to rise, and life expectancy to fall. As an aside, and stated in the extreme, human immortality—which does not exist anyway—is obviously not what makes the world great and amazing. I hope we can see our way to acceptance that death is natural—not an evil to be defeated—and a fair price for the privilege of living in a biodiverse, ecologically sustainable “paradise” in an otherwise empty and hostile space. Since the current low levels of mortality go hand-in-hand with ecological devastation and a doomed modernity, their embrace is itself a problem (yes, I’m really swimming against the current now!). So, in the farther future—likely lacking medical birth control—I can envision higher birth rates balanced by higher death rates for a reasonable and comfortable stability in right-relationship to the community of life. Earth back in balance. Good, right?

How we get from here to there is likely to be turbulent and is difficult to predict. Rather than accepting and adapting smartly, the transition may be marked by violence and war, and/or by simple starvation as complex food production/distribution networks fragment. Either way, I would not be surprised if mortality rates rise significantly during the transition, making the population decline sharper than any mainstream model is courageous enough to explore. Meanwhile, birth rates may stay low as a result of turbulence, or could conceivably experience an uptick as birth control becomes unavailable and young couples seek after-dark entertainment when screens are no longer prevalent.

In any case, smooth convergence to a “final” fertility rate as modeled by the U.N. is about the last thing that I imagine will actually happen. Roller coaster is more our jam.

Repercussions

Presently, “healthy” economies depend on growth. Decline is no bueno, in political and economic sectors. A horizon of opportunity and expansion becomes a horizon of empty buildings, closed shops, shuttered schools, withering supply chains, and generally scaled-back lifestyles. Economies also depend on optimism and the idea that tomorrow will be bigger than today. Take that away, and what happens to investment? We’re talking about an event that makes the Great Depression look like a month-long visit of the in-laws: unpleasant, but you can have some faith that you’ll get through it—even if it lasts longer than seems reasonable. In the population decline case, we’re confronting the possibility of a generations-long—or even indefinite—phenomenon during which institutions, supply chains, and industrial food production/distribution falter. When the longstanding normalcy is shattered, when food security is a thing of the past, and when no credible reprieve is in sight, how will people view procreation? Birth rates will never drop to zero, but all things considered population growth also seems unlikely to rally amidst disorienting uncertainty.

One bright spot is that because different countries are at different stages of demographic development (age distributions, fertility rates), a handful already appear to be past their peak, including China! The game has already started, and should pick up steam. Thus, well before global population peaks, we’ll have example after example of “early adopters,” and as such possess convincing evidence of the global peak to come, and furthermore may draw useful lessons from the outcomes. These “test runs” may help soften the experience globally, by allowing others to avoid repeating mistakes in accepting and adapting to the new reality..

In the past, I assumed that modernity would fail (bomb) under the weight of resource shortages, technological disappointments, exploding debt and financial collapse, ecological/biodiversity collapse, resource wars, or most likely a swirling, confusing mix of all of the above. Now, I can imagine the depopulation dynamic acting as a leading agent in the great story of how humans slough off modernity, giving the more-than-human world breathing room to recover. In some ways, this is the gentlest, most humane exit strategy, and may represent a smarter-than-expected proactive reaction to the limits that are increasingly obvious: we’d be dodging the worst by deflating the balloon before it pops.

The juggernaut simply runs out of steam, as people stop believing in the fantasy—in reaction to hollowing institutions—and get on with inventing other ways to survive that are more locally-reliant and place-specific. No more one-size-fits-all, top-down approach to living, but a fragmented diversity of living arrangements that go back to being tested on the grounds of biophysical/ecological viability in relation to the community of life. The economy as we know it will gasp and die, but people will find they’re made of sterner stuff , based on a much older genetic heritage.

As population bombs, perhaps there’s no explosion, but a whimper of modernity as the larger living world finds its voice again, accented by human song.

Next post in this series on near-term population peak.

Views: 7488

Taking into account studies that show a decrease in the reproductive qualities of sperm, it is safe to say that the decrease in the population level will not take long.

To add to the conundrum, check out Nate Hagen's Great Simplification dialogues Numbers 37 [Sept. 21, 2020], and Shawna Swan on 'fertility' [Number 2, Jan., 2022]. Seems that despite so much white nationalism across U.S./Canada and much of Europe, most people do not realize that population decline is the "worst thing to happen" for any future of "growth" without large and increasing immigration. This, of course, means "people not like us"!

I too would prefer a future where human population implodes by itself and we have a soft landing, The fatalist skeptic in me happily derides this as a bunch of wishful thinking but who knows, Perhaps the microplastics in the water will castrate us all.

The point of the post is that nothing particularly drastic has to happen: just continuing recent trends. Fertility is falling fast around the world, and much faster than the projections tolerate. To me, the "wishful" thinking is more on the part of those who see a late and high peak (which seems like a plus to those less aware of the meta-crisis). To be clear, my preferences don't have anything to do with what's actually transpiring in the world right now, which seems to be aiming for a peak lower and sooner than many imagined.

"The point of the post is that nothing particularly drastic has to happen: just continuing recent trends." – Tom Murphy in 2024

"To destroy life as we know it, all we have to do is keep doing exactly what we are doing". – James Gustave Speth in 2008

"In nature there are no rewards or punishments, only consequences." – Robert Green Ingersoll in 1881

Excellent post!

We don’t only have declining populations but we also have increasingly sick populations as a result of many factors. PFAS pollution found in rain on every continent just to name one. Even if we stop the pollution it’s already in the biosphere. Last time I checked cancer rates were going up again and particularly under young adults. Sigh, we are a very strange species.

Dan Brown ‘s character in Inferno – Bertrand Zobrist – details the problem of exponential growth in global population and presents the solution of a virus with gene coding imprinting that renders over 90% of infected males infertile, thus heralding a fairly rapid decline in humanity. Unfortunately aerosol depletion and the tricky issue of nuclear fuel instability wasn’t explored.

Long before Brown’s novel, Dr Albert Bartlett would regularly lecture his class in Colorado on this very subject and I’m sure would concur with your submission here.

The small island archipelago of St Kilda, fifty miles west of the Scottish Hebrides, was inhabited for over 3,000 years until it was evacuated in 1930. The population fluctuated between 120 and 280 where church records exist back to the 16C, and was a remarkable example of sustainable living until it was evacuated in 1930. Why did it fail?

There was a catastrophic increase in infant mortality in the 19C principally due to neonatal tetanus, initially thought to be from fulmar oil used for cleaning the umbilical cord during resection. This was thought to be ‘best practice’ by the church and nurses employed by the ministries. A recent paper suggests unhygienic instruments and certainly, by the early 1900s and improvements in surgical/obstetric practice, infant mortality from neonatal tetanus had fallen significantly – and had there not been other factors, the island could still have a sustainable, indigenous population living there.

Unfortunately, the British government had other ideas – the island was evacuated and eventually used as a military base and radar station.

It is, however, a wonderful example of sustainable living, a simple pre-modernity existence that worked for centuries.

https://www.rcpe.ac.uk/sites/default/files/stride_14.pdf

Yep. Though decline is inevitable, the process will be a roller coaster. As they say, the devil will be in the details. I believe that the ride down (especially in the USA) will be made more challenging by those devilish demographic details. All one has to do is look at a map. Though birth rates in the US are stagnant, population pressure from the south is relentless. Yes, the overall birth rate in Latin America is declining, but that doesn't tell the whole story. The US replacement rate stands at 1.7, while many Latin American countries are at or well above the 2.1 mark: Belize, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Grenada, Guatemala, Guyana, Haiti, Honduras, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Suriname, Venezuela, and the US Virgin Islands, to name several. Couple this fact with deadly heat increases in the South, and you have a wave of folks heading to the relatively wide open and empty North. I think this fact plays a huge role in the white angst and white nativism that we see in the US today. And it's only going to continue, creating a turbulent, violent and dangerous environment. Similar scenarios will probably play out globally.

"Since the current low levels of mortality go hand-in-hand with ecological devastation and a doomed modernity, their embrace is itself a problem…"

Of course, what enabled the decrease in mortality rates around the world since the Industrial Revolution was the easy access to fossil fuels, which powered modernity. There is a book by Vaclav Smil that chronicles how our modern way of life is addicted to fossil fuels: "How the World Really Works."

As Bruce says above, lower fertility may impact future scenarios, due to rapidly increasing environmental pollution. I just saw a study yesterday about researchers who sampled testes of dogs, mice, and humans, and found microplastics in every sample. They showed that dogs with higher microplastics in their testes had lower fertility. They haven't yet tested ovaries, but expect to find microplastics there too (after all, they are everywhere else tested so far in the human body and mice bodies). Human male fertility has already dropped 50%. Given that plastic production (the source of microplastics as well as a source of phthalates which is one probable cause of fertility drop) is expected to triple or quadruple in the next 2-3 decades, I wonder what the long term ramifications will be on fertility for all mammals on Earth exposed to the 10,000 or so chemicals in plastic and the micro- and nano-plastics they create.

The other thing I'm seeing is an increase in pro-natalism; stories about people panicking about the drop in population growth, and frantically having as many kids as they can. I'm guessing these people are a tiny fraction of the population as a whole, but it's interesting to see that cultural phenomenon developing in response to the drop in reproduction.

Yes, but how selfish and cruel is that! Who in their right mind would think it right to bring a child into the world right now?

Sorry that was impulsive and not directed to you, but why would anyone think that having more children is a good idea right now? Is there really anyone who thinks humanity will survive beyond this century? We’re unable to cope with the environmental changes, never mind the sociological challenges that confront us, therefore we must accept our fate and try to restore and prevent further damage to life on this planet in the time we have left.

We are the architects of our own demise; we have let our emotions and desires conquer reason and intellect – and quite properly and not before time, we are being punished. Why burden another generation with our failure?

Thanks for the self-moderation, there!

I make a point to differentiate humanity from modernity. Do I think modernity will survive beyond this century? Seems unlikely. Do I think humanity will: almost certainly. For one thing, Indigenous people who never adopted the ways of modernity and still have access to sustainable ways of living in right-relationship to the community of life could do fine once modernity is not threatening anymore and nature begins bouncing back. Climate change will be a gift that keeps giving, but not necessarily at extinction levels.

I can replace most of your "we" and "our" above with versions of "modernity" and agree. But that's not to say all humans.

Several years ago when I was looking through some sewage samples for microplastics I observed a lot of fibres and not much else in the way of plastic. Quite a large portion of the micro and nanoplastics in the environment are derived from synthetic fabrics used in clothing and for interior furnishings and carpets. Quite a few of the plastics that are used by people for everything are quite inert and have been used for implants of various types in the body without problems for decades. Some plastics such as Gore Tex (expanded Teflon) are highly absorbent, similar to activated charcoal, and will absorb most organic chemicals, but they generally eventually settle out in the environment and become part of the sediment. The nano-plastics that are found in the biological samples are super tiny and probably not capable of absorbing much.

In the complex world of biological systems it is pretty hard to find any links between things like plastic use and lower fertility rates because so many things are happening at the same time and it is super hard to find definitive evidence.

Modernity is a giant uncontrolled experiment.

If we tried to replace plastic with "natural" things, especially fibres we would have to devote vast areas of land to growing fibre crops like cotton, hemp, and wool (sheep) and I don't think we have enough land to do that without widespread food shortages.

Delhi had a record 52.9 C. today. Temperatures, CO2 emissions ,Ice , increasing climatic instability ,all mean that the food supply to feed an increasing population over the next few decades probably won't be there.

Some interesting points in this paper :

https://www.mdpi.com/2673-4060/4/3/34

Delhi's previous record was yesterday,with 49.9 C..

https://www.theguardian.com/world/article/2024/jun/01/sensor-error-means-new-delhi-heatwave-record-overstated-by-3c

Just a note that population decline in the BAU2 model looks to me to be directly related to declining food supply. That's a little scary, but it's not at all the driver for declining birth rates now. I would imagine the Club of Rome did not account for widespread availability of birth control coupled with increasing education and empowerment of women.

Actually, the LtG work (commissioned but not performed by the Club of Rome) intently pursued widespread birth control and other child-bearing policies in their modeling (plenty awareness of birth control and importance of female education in 1972). The proximate cause for collapse they cite in the BAU2 run is unaway pollution (which itself then curtails food production. At least that's my understanding of the causal linkages in their run.

That's my understanding of L2G BAU models too. I think we're seeing very clearly the "runaway pollution" right now, although I'm sure it will get much, much worse before it gets better.

With 2.3% growth in gross world product (required to keep the economy from recession, depression, and collapse) the human enterprise will double in 35 or so years, meaning (roughly) doubling the pollution we already see (as I understand it, let me know if I'm wrong). Given that every raindrop has PFAs and every breath we take and food morsel we eat has microplastics, it's hard to imagine how much worse it can get, but I think we'll find out, unless population does indeed start dropping fast before modernity can do too much more damage.

Very thought-provoking post, Tom. I wouldn't see depopulation by low fertility so much as an agent in 'sloughing off modernity' as our best hope of retaining the best aspects of modernity and avoiding high mortality rates. But it might not be as imminent as you hope.

The main fly in the ointment is that the UN has been consistently overestimating fertility decline in the remaining high-fertility countries. See https://doi.org/10.3390/world4030034 (open access article) for a full discussion. This means that the steep decline in global growth rate in recent years (on which your extrapolation is based) is at least partly an artifact of their model – the next revision will most likely push the flattish section at the start of your extrapolation out a bit further, but still 'report' a rapid decline over the past decade, as an artifact of their model. (The recent past estimates are more modelled than measured.) The problem with these countries having recalcitrantly slow fertility decline is that they are steadily becoming a bigger share of the global population, so they have greater influence on the global average fertility.

But the other issue the UN has not been anticipating well is the continued decline to very low fertility levels in east Asia. The pandemic disruption seems to have dissuaded some couples from having children (yet) and we don't yet know if TFR will bounce back. Nor do we know how low it will get. While it was only the Caucasian billion that had low fertility, whether it fell further or rebound made very little difference to world projections. But with China approaching TFR of 1, it's a different kettle of fish. But sub-Saharan Africa's population is now bigger than China's, so whether SSA's fertility falls a little faster or slower will have much more impact than whether China's settles nearer 1 or 1.5.

In short, don't count your chickens yet!

You make a very interesting point. I have followed your work on immigration in Australia, Dr. O'Sullivan, and find your views very compelling. As a civil engineer and scientist, I appreciate your views. I find your pragmatism refreshing. Indeed, we should absolutely be concerned with things such as available housing, public services, etc. that migration will bring to urban areas.

With respect to over population and demographics it seems to me that the real question is "when is the population density larger than the carrying capacity?" This obviously depends on any nation's ability to provide resources to their people, and in some nations a large influx of migration can be overwhelming. Take for example Pakistan, which has seen a wide range in the 'net immigration' numbers over time. https://www.worldometers.info/world-population/pakistan-population/ Two periods stand out for having an abnormally large influx of migration, the 1980's and the 2000's. The influx in 1980 was due to Afghan refugees fleeing the Soviet occupation of their homeland. https://www.graduateinstitute.ch/sites/internet/files/2018-12/4868daad2.pdf

Any nation with a weak or corrupt government is unprepared to deal with a massive influx of refugees. In Pakistan, the result of higher population, lack of jobs, and weak government resulted in illegal timber harvesting in the mountainous region. This in turn has had a disastrous impact on flooding and agriculture. Climate change, heavier rain events, flood prone slopes in the mountains are making it extremely difficult for Pakistan to support its growing population.

Carrying capacity is not simply a biological limit, it is also geopolitical. We rely on strong government controls and regional planning to control an influx of immigration. Developed nations may be witnessing a reduction in population and it could be made up by an influx of immigrants, but who do we allow in and what citizenship rights do we accord them? Do we have the infrastructure to accommodate them? When do we accord them the same rights as current citizens?

Humans have long been able to move to new locations when they exceeded local carrying capacity or when weather and climate changed regional resources. This is not the case today. We face a number of issues including rising environmental toxins that are likely limiting fertility, geopolitical instability that is increasing refugees, and worsening climatic conditions. We seem ill-equipped to deal with any of these issues.

Hi Jody, migration is a bit off-topic here, but Pakistan's growth has been driven overwhelmingly by high birth rates, not migration. Since 2000, it has had far more people leaving than arriving. Corrupt and inept governance is also a feature of rapid population growth, since no honest government can make headway against such expanding needs so they lose power, and the leaders that retain it are those willing to undermine democracy to stay in power.

It's noteworthy that Bangladesh, having been cast off by Pakistan as a basket-case, turned things around through their family planning program, and have now overtaken Pakistan's GDP per capita.

Thanks, Jane, for having a look and offering insights. If the rapid downward trend of the last decade is an artificial model output, then indeed that changes my whole story. I am left confused in this case: 1) Why would the same model then correct itself abruptly in the TFR plot at 2020 (internal inconsistency)? 2) What portion of this plot https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Fertility_rate_in_OECD.svg (although just OECD) is untrustworthy? 3) I can appreciate that it is difficult to accurately assess current population, but in much of the world I would naively expect that counting annual births and deaths is relatively straightforward (recorded events), as is a reasonable-enough capture of female reproductive-age population so that a reasonable TFR can be computed (within 5% or better) pretty-much real-time (not requiring a model with decade-scale artificiality). But, I've been surprised before.

The other big question is the extent to which Africa's high birth rates and low death rates depend on stability in the rest of the world for influx of food, medicine, supplies, etc. I get it that high growth rates in a large subset of global population can overwhelm low rates elsewhere, but it seems that maintaining the situation is contextually contingent on the present, temporary world order. I suspect that demographic models do not tangle in the unprecedented and unpredictable realms of oil supply, ecological and agricultural failures (related), global resource wars, and a host of other influences because it's basically impossible to cast in model form, with a straight face. Any model therefore rests on some underlying assumption of no major changes to decades-long trajectories, which becomes suspect in a grossly unsustainable system in overshoot.

"I suspect that demographic models do not tangle in the unprecedented and unpredictable realms of oil supply…and a host of other influences because it's basically impossible to cast in model form…"

Impossible to cast in model form?

See MIT study in 1972. It's not only possible to cast a host of influences in model form but the scenarios generated by World3 have been shown to be quite accurate.

The "host of influences" are "unprecedented and unpredictable"?

Energy (oil supply today), ecology (now global destruction today instead of regional), food (industrial agriculture today), resource wars, climate change, social instability – all have impacted human societies for millennia, with basically the same outcome – groups, societies, empires, all rise and fall.

Generally nothing unprecedented or unpredictable about that. And a good reading of ancient and modern history shows patterns and even details that we should recognize are occurring today.

But yes, it's correct to say that any model that invokes "ceteris paribus" is not just suspect but will eventually lead to a distorted and damaging understanding of reality. And it's that analytical approach that brought us to the precipice that we peer over today.

It was always going to turn out this way. This is what it means to be human. It's in our DNA. We will always avoid putting limits on ourselves that prevent us from "wants". You know, greed, max power principle, ego-driven desire…

Nature doesn't care. And when biogeophysical limits are reached, nature will do what it has always done, without prejudice. But it's also human to weep. The human-caused collapse of biodiversity that threatens human existence is, of course, ironic and insulting and ignorant. But unbounded, it's simply what "life" does.

Anyway, World3 succeeded in attempting to glimpse what the outcome would be if the major variables ("host of influences") of modern civ were modeled together and not studied in situ or in silo.

World3 is not perfect, of course, but it's consistent with what we know about human history, biological carrying capacity, and thermodynamics.

"All models are wrong, but some are useful". For obvious reasons.

Right: you may have noticed the World3 (LtG) plots included in the post. These sorts of things are what I have in mind when I ask if demographic models like that used by the U.N. approach the problem holistically (knowing they don't). As a result, the output is disconnected from a host of other interrelated factors. World3 indicated the sorts of things that happen when performing whole-system modeling, although getting it "right" is a fool's errand (which LtG was not trying to do, but I suspect U.N. *is*). The important thing is to expose credible/likely modes that emerge, while admitting a wide range of credible "background" realities.

Hi Tom, with regard to your TFR chart, the aberration that matters is the shoulder in the African line, that says the deceleration that happened through 1995-2010 doesn't last and rapid fertility decline resumes. It seems that vital statistics (births and deaths) are still far from fully recorded in those countries, and the extent of revisions from one UN release to the next have been quite large for some.

For the other lines, I can only surmise that the recent dip is assumed not to last. It's not a consistent feature of the OECD data to which you link. As for the OECD data, would you not agree that it shows TFR pretty stable for OECD countries over the past three decades, with the exceptions of Mexico and Chile (still completing their transition) and South Korea's further decline in the past decade? The latter was unexpected. I suspect it might relate to Korea reaching an unusually high peak in the proportion of working-age people (due to its very rapid fertility decline in the 60s & 70s) meaning a very competitive labour market and big career penalties for motherhood. As its population starts declining, the labour market will tighten and employers will be more willing to accommodate maternity leave and more flexibility for mothers. Whether that lifts TFR is only conjecture.

You're right about projections not accounting for resource scarcity and resultant increases in mortality. My concern is that those who point to a sooner peak and decline in world population due to fertility decline understate the risks of that happening and infer that we don't have to make greater efforts to avoid it. Anyone who says fertility decline is on-track in sub-Saharan Africa is guilty of condemning Africans to an even poorer and more violent future.

Agreed that much depends on African progress, and I would not want the rapid downward trend to stall or moderate significantly.

The OECD link I provided does convey an impressive stability from 1990 to 2010, but after 2016 gives a strong impression of universal downward trend among virtually all countries plotted, which lines up with the TFR down-trend in the U.N. data. In that U.N. plot, I assume that births/deaths are well tracked in many/most of the regions showing fast decline (thus a reality more so than a model error). No matter what, the future evolution is a matter of conjecture, which is a large part of my point: a false sense of confidence in the projections. The actual world will appear to have a "mind of its own," responsive to numerous dynamical factors—some of which we may not be aware.

I sympathize with the point that we would not want the things we say to impact the evolution, but I suspect the driving forces are not likely to be buffeted by (at least my) words.

You often bring up the notion of ecological balance, and appear to characterise it as a "paradise." I'm not so sure. For a start, prior to civilisation, just about all creatures would die horribly from predation, injuries, disease or famine. This is the natural way of things. Secondly, the history of this planet is anything but balance, overall. Indeed, it is probably the frequent imbalances that boosted evolution, eventually leading to a species that thinks it has surpassed evolution but is able to wreak far more destruction on the biosphere than any other species.

However, I sometimes garner some hope from uncontacted tribes which still live as they did thousands of years ago. Is it really sustainable (sounds close) and is it possible for some parts of humanity to not act like a species? Despite that hope, I can't help feeling that such living is impossible, at least over the very long term. Given that they have all the abilities of humans (they are humans, after all) how can they possibly restrain themselves from applying those abilities to make their own lives more comfortable? That doesn't seem like a species.

Since modernity is so egregiously *out* of anything resembling balance, what I advocate is steering toward something like balance–recognizing of course that it's a moving target and always has been. The important thing is to tuck back into the flow governed by ecological relationships and changing via co-evolution. No mistake that living this way sacrifices many of the temporary comforts and cheats we have come to expect.

The fact that 95% of Homo sapiens' time on the planet was in the mode of "uncontacted tribes" allows me to see ourselves as the aberration uncharacteristic of our species. That may be wrong in the end, and humans may be a self-defeating lost cause (excessive, maladaptive intelligence). But, the fact that humans lived in ecological context for so long suggests it's not impossible.

I almost whole-heartedly agree but I don't think that humans living in ecological context for so long suggests it's not impossible. The fact that there are so few humans now living in that mode suggests that it is, in practice, impossible for humans as a whole, and definitely over a prolonged period measured in millennia. But I guess a few millennia of it would be far preferable to what we see happening now. (Of course, "preferable" is a matter of opinion; nature doesn't care).

Surely you can't be serious. The Australian Aboriginals lived here for over 50,000 years, and at the end of that time, every early Australian European explorer waxed lyrical on the robust health and abundant life of ecosystems throughout Australian . The fact that there are so few indigenous tribes now living in similar ways is a result of the industrial juggernaut either exterminating those societies, or claiming the land on which they existed.

Industrial civilisation is riddled with systemic flaws that guarantee it won't persist for long, probably beyond this century. Those systemic flaws did not exist in hunter-gatherer societies. One system existed for 50,000 years, and at the end of that time, the ecosystems were in robust health. The other will last maybe three hundred years, and leave a wasteland in its wake.

You've expanded on my argument. Industrial civilisation was inevitable once fossil fuels were discovered to be readily available (and industrialisation made them more available). 50,000 years is a long time, a very long time, but that just shows how not discovering a rich energy source can suppress what we might now call "progress" but is really ecosystem destruction. The early civilisations arose before readily available concentrated energy sources. I've little doubt that would happen again in the same circumstances,

Perhaps. It's worth noting, though, that there were many indigenous societies, who actively avoided the agricultural path, though they were well aware of it. Similar to the Andaman Islanders today, though not as successful (so far) at preventing the destruction of their preferred lifestyle. You've probably read "The Original Affluent Society " . Plenty of time in indigenous societies for socialising, cultural festivities, etc. Not Dawn to Dusk scrabbling, as most seem to think. Did they suffer pain in life, then die ? Sure. Do we suffer pain in life, then die ? Did violence exist ? Sure. Does violence exist now ?

Anyway. We are here now. Maybe this quote from William Catton sums up modernity :

" The point of this talk. is simply that reliance on non-renewable natural resources (NNR s) which enabled us to do more things than we did before we began that reliance, has made us vulnerable. Such reliance is a commitment to impermanence. "

I’ve been reading the sometimes prescient essays from 1964 by the astrophysicist and SF writer, Sir Fred Hoyle (Of Men and Galaxies). He remarks that the most obvious prognostication is that the population of the world is going to rise with several consequences, including that is a good idea to buy real estate. Other consequences include a rise in social pressure, and in affluent countries where basic needs are satisfied, a central role of the quest for status. But eventually he transitions to the big Kahuna that Tom has so elegantly explored in Do the Math: “It has often been said that, if the human species fails to make a go of it here on Earth, some other species will take over the running. In the sense of developing intelligence this is not correct. We have, or soon will have, exhausted the necessary physical prerequisites so far as this planet is concerned. With coal gone, oil gone, high-grade metallic ores gone, no species however competent can make the long climb from primitive conditions to high-level technology. This is a one-shot affair. If we fail, this planetary system fails so far as intelligence is concerned. The same will be true of other planetary systems. On each of them there will be one chance, and one chance only.” (By intelligence in this passage, I believe he's referring to a modernist civilization.)

Interesting: had not seen that before. I agree that it's one shot, but disagree that the one shot has a chance at long-term success. The technological mode we've adopted is out of context with respect to ecology and evolution, so that its material requirements are not regenerated and supported by a web of life and thus a dead end. As for intelligence, many forms exist that we don't acknowledge because it's not *our* brand of intelligence. It could be that our brand is ecologically incompatible once taken too far (as it allows hyper-evolution outside the norms of biological evolution, quickly disconnecting us from the living world to our own ultimate peril).

Hoyle shared the common mid-century belief that nuclear reactors would provide essentially limitless energy to the human technological enterprise. He and others were wrong about a nuclear powered future, but also failed to appreciate that limitless energy would likely enable humans to annihilate their ecological surround. In conjunction, these processes and limits makes the "Fermi Paradox" appear not to be paradoxical all. And I agree that we are, as the Buddhists say, surrounded by sentient beings that most disregard.

Ok, but he did discover stellar nucleosynthesis – that's a pretty good achievement.