This is part of a series of posts representing ideas from the book, Ishmael, by Daniel Quinn. I view the ideas explored in Ishmael to be so important to the world that it seems everyone should have a chance to be exposed. I hope this treatment inspires you to read the original.

In the Foreword to the 25th anniversary printing, starting on page xxiv, Daniel Quinn offers seven pages of additional material that he suggests could be appended to what is already the longest chapter in the book. The audiobook I listened to rolls right into this material at the end of Chapter 9 without pausing to indicate that it was not in the original.

Rather than making the Chapter 9 post even longer than it already is, I decided to make a separate entry for this material (also inserted into the schedule so-as not to disrupt the normal cadence of two “real” chapters per week).

Unlike the original content, this addendum is not split into numbered sections. I create section headings all the same just to break things up a bit.

Population Surge

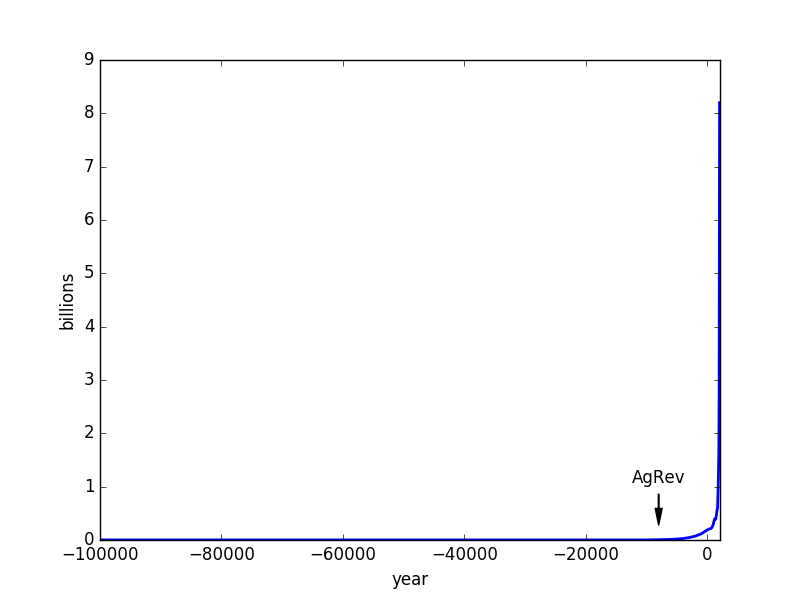

In the context of asking Alan what fate he imagined we faced, Ishmael presented a plot of human population over the last 100,000 years. I don’t need to show it to you, right? It looks pretty-much like an upper-case L tipped 90 degrees counter-clockwise. At 90% of the way along the graph—at the start of the agricultural revolution—population is less than 0.1% of today’s value: basically invisible, hugging the bottom axis. At 99% of the way along, it’s still less than 4% of today’s level [the cartoon graph in the book actually understates the starkness of the rise; see my own version below].

Some quibbling ensues about the choice of start date on the graph, but since the line does not begin at zero population, all is fine. For all this, Alan [still slow after 25 years!] fails to see how the graph is relevant to the question about our fate as a species.

Ishmael speculates that we are so inured to this shocking phenomenon that it fails to register as breathtaking and frightening. Had the plot applied to badgers, for instance, our eyeballs might pop out of their sockets: it would clearly indicate that something was seriously out of whack. Ishmael was disturbed by the degree to which Alan remained undisturbed.

The Sixth Mass Extinction

Injecting a bit of “future” knowledge into this passage, Ishmael speaks of Charles Atterley, known as “B” in Europe, who is going around the continent delivering underground lectures on related material to a dedicated following [see the “sequel” book The Story of B]. In a recent letter, Atterley updates Ishmael on the fact that biologists around the world are in agreement that a sixth mass extinction is underway. The exponential population graph has a mirror in extinctions, now transpiring at 1,000 times the natural rate: all down to humans.

Alan suggests that if elevated extinction rates are human-made, then perhaps they might be human-unmade. Perhaps, offers Ishmael, but this is impossible under the prevailing mindset. As long as we prioritize human well-being to the exclusion of the rest of the community of life, we make ourselves enemies of life. By increasing annual food production to “solve” hunger, we have surged to 8 billion in a few centuries. Without changing our mentality, we will not un-make the unfolding pattern of extinctions.

Quinn (via Ishmael) speculates that one billion humans might be indefinitely sustainable [I have my doubts]. In any case, a huge mental shift is needed if we are to deliberately pull back from the brink. It’s no small order: billions would have to change their mindset before the tide would turn.

Food Makes Babies, Again

Alan remains unconvinced about the formula that increased food production drives human population up [that such a crude biological relationship would apply to godly humans]. Ishmael counters that the dramatic rise in population deserves some explanation, and retools the argument.

First, Ishmael checks whether Alan agrees that if we have more people, we need to produce more food. “Certainly.”

Well, where did “more people” come from? How is it that population doubled in a mere 40 years? Such a biophysical anomaly demands a biophysical explanation. Death didn’t “take a holiday.” Did the surge come out of nowhere? Was it utterly spontaneous? [And what do we make of its perfect coincidence with mechanized agriculture and fossil fuels (the Green Revolution)?]

Ishmael points to Peter Farb and Thomas Malthus regarding the food–population connection. Malthus recognized the incompatibility of exponential population growth and finite (linear) agricultural potential. He also wondered how it is that more mouths appear, needing to be fed. He noted that increased food capacity enabled population growth.

Changing Mentality

If humans are to un-make the metacrisis, it must start with a change of mentality: a refusal to answer population growth with more food in an endless positive feedback loop [positive feedback leads to exponential runaway: not a “good” feedback, despite the positive “vibe” of “positive.”]

Alan asks: Won’t this refusal lead to worldwide famine and starvation? Ishmael: Why should it? Holding food production steady provides enough food for the current population. The madness has to stop, somehow.

But could we even hold steady at current rates? Would that reverse the damages and defuse the sixth mass extinction? Ishmael admits that: no, it’s not enough. But halting growth is a crucially-important first step. Dialing down necessarily involves the cessation of going up.

The Hard Descent

So, what follows this first step of halting growth? Ishmael acknowledges that stopping growth is easy compared to the next part. Temporary as they must be, the “gains” of modernity continue to coddle us if we only halt growth. It is the path down that will take a heavy toll—perhaps unpleasant enough to make extinction seem preferable.

Quinn again speculates that one billion humans might be maintained indefinitely, but correctly notes that we need not set a target in advance. If we find that one billion is still too much, we continue the downward glideslope. The process would take a century or two—becoming normal/routine, and even instinctive. Only by accepting this transition will we earn our moniker of Homo sapiens.

Alan, in a decent capture of how many react to such propositions, erupts in indignation over the prospect of purposeful population descent:

What ‘process’ are you talking about? Wholesale genocide? Everyday extermination of female infants? Genetically-engineered epidemics spread globally? Do you think we’re capable of atrocities like that?

Ishmael’s reaction is similar to my own: don’t be absurd. [It’s an unnecessary but perfectly predictable tantrum, in reaction to the offensive suggestion that humans face limits and are not entitled to anything we wish.] Ishmael observes that if a newspaper suggested ending the sixth mass extinction by attending to human population and shepherding it to lower numbers, the comments section would blow up with manufactured and hyperbolic atrocities of every flavor. The prospect strikes a deep nerve, which is revealing.

[As I believe we are likely to witness this century, global population can go down by demographic dynamics alone—influenced by a growing host of negative feedback factors that are causing fertility rates to plummet: no one need die of “atrocity.” Every person has no choice but to die, eventually, as an absolute certainty. Bringing new humans into the world is not comparably certain, and this flexibility alone is capable of a surprisingly quick population descent. See my video and related posts.]

Invent

Ishmael clarifies that he suggests no such program of atrocity [see note above]. But, Alan wonders, what is Ishmael proposing?

“You’re a tremendously inventive people, aren’t you? … Then invent.”

Alan is disappointed not to receive a packaged answer [Takers love their programs], but Ishmael points out that this whole process is meant to draw answers out of Alan, not plant them into a passive pupil.

Next Time

In the next installment, Chapter 10 turns into a novel again before Ishmael reluctantly resumes the lesson plan.

I thank Alex Leff for looking over a draft of this post and offering valuable comments and suggestions.

Views: 1350

Hi Tom. First comment, as I have recently come across your blog, and I read the Ishmael book on your recommendation.

I think the whole argument of expanding food production (being the decisive factor in population growth) in the book is a weak one that is being shown to be incorrect by the reducing rate of population growth in most continents and a predicted peak and decline of world population even under BAU conditions. (It may have been a reasonable argument 25 years ago, but not so much today.)

This of course is good news and means there is a better chance of getting to a sustainable, survivable planet. Your thoughts?

BTW, I'd like to have a solid understanding when talking to other people. Also can you point me to good references/resources for extinction rate estimates?

Thanks for your mahi.

Daniel Quinn's repeated argument that food makes babies seems to generate more resistance than any other (likely why he keeps coming back to it in future works). I can't tell how much of the reaction is due to a "we're not like animals, goddammit" objection. "We're better than that."

The outcome of a thought (or actual) experiment in which the rate of food provision is controlled for a captive population (of bacteria, crickets, mice, deer, chimps, humans?) is very clear: the population will adjust to the available food. Once stabilized on a steady input, decreasing the food will decrease the population—guaranteed (humans of course as well: no doubt at all). Increase food and population will tend to increase.

Ah, but does it *have* to? This is where I think most people get hung up: theory vs. experiment. No: in theory it doesn't *have* to. But does it in practice? Yes, as a rule.

So, it might be useful to make the distinction between: MUST it, or HAS it? I would say it certainly *has*, in practice. Two enormous pillars of evidence: first, agriculture changed food availability, locking in surplus, on the whole. That key development just happens (!) to mark the point when human population began exponential increase. Coincidence? Well, had the surplus NOT been made available, we can be absolutely *sure* no population growth would have occurred, right? Must it have happened? Theoretically, no. Did it, in practice? Absolutely. The second instance is the Green Revolution. Intensifying agriculture using fossil fuels was not in *response* to a giant boom in population and soaring global famine. It *created* the conditions in which human population could (and DID) surge to a degree never seen on this planet. It was more of a: "hey, look what we can do with fertilizer and diesel: make more food than we did before on the same land."

It's a positive feedback situation that has persisted for millennia. The dots are not hard to connect, even if we have a theoretical bias against the *necessity* of the causation. Positive feedback cannot obtain forever. Negative feedback mechanisms that have been absent or overpowered rise when population becomes increasingly problematic. It can be subtle and take many forms. Ask young people why they are not having children and you'll get a dozen or more different (valid) reasons that relate to current conditions that are present today and weren't so much for the preceding millennia. This is negative feedback in many forms, all acting in parallel. It had to happen, eventually, as exponential growth (positive feedback dominance) never lasts. But the ultimate overpowerment of positive feedback does not invalidate the associated dynamics that prevailed leading up to this point—for many thousands of years. The "look, it's changing now" line doesn't wipe the historical connection.

Had population *not* increased coincident with the advent of agriculture or the Green Revolution, the argument against the "food makes babies" relationship would be on solid ground. It's not what happened, which makes the consistency of objection something of a fascinating phenomenon, to me. It touches a nerve, apparently.

Certainly an increase in food in the past has enabled an increase in the population. Of course. And in the future, our population is bounded by the quantity of food we could obtain (/produce).

However it seems that the past (population following food production) is not the same as the present, where in the wealthy world (Europe and most of Asia and the Americas) birth rates are below replacement level despite people still being able afford enough food to feed larger families if they wished.

The exception is much of Africa and some other nations where population is still expanding as much as food resources allow. (I.e. still sticking to the same patterns we saw in the past.)

A common explanation links this to security of food/basic needs/retirement income. The argument would be that if food production is labour intensive and there is no retirement provision other than having children, you want to have as big a family as you can. And overall population expands to the boundary of the food resources available.

However, I'd posit the future doesn't have to be the same as the past, and indeed in many parts of the world it already isn't. I'd argue human culture can limit our population to a size lower than the food bound. And this is already happening.

This is what Ishmael wants, and it's what most of us would surely prefer so we can scale our human population down to fit better on the earth.

Are we actually in disagreement?

In the future population will reduce and food production will reduce. If this happens through widespread famine and war over resources, then we could probably agree population continues to be limited by the food available. But if we manage to avoid those scenarios, and particularly if we're able to choose a population lower (and wealthier in some ways) than the largest possible population, then surely we'd agree we have managed to achieve a decoupling?

Again, I'm not arguing that the "food makes babies" relationship wasn't present in the past, but it seems to me this is changing, and need not be the determining factor in the future. Of course there is an upper limit beyond which we cannot go (and the upper limit will be reducing as time goes on,) but whether we can get ahead of the limit with a faster reducing population would seem to be a critical determinant of whether our degrowth will be happy or not. No?

Thanks

I don't think we're in much disagreement here. Of course the future need not (and cannot) look like the past when positive feedback and exponentials are involved. I expect that human population will be perhaps half what it is now in 100 years, and possibly below 1 billion in 200 years (as the accumulated ecological damage, resource exploitation, instability of decline become the new normal for a while). Famine will likely play a role in some parts of the world (not a monolithic single one-size-fits-all saga).

It's good that you can accept the "food makes babies" argument for the past. Many moderns are unable to cede that animalistic, biological nature to godly humans. Quinn was mainly stressing this formula for how we got here, but in his experience of the decades prior to 1992, it seemed like sheer lunacy to keep increasing food production and expect a different outcome. I could see the rapid fertility decline in progress as unwillingness to keep perpetuating a world out of control (getting ahead of things), but this is not by careful design or planning: the brokers of modernity are freaked out by it, in fact. They are not in control of it, and it has the potential to create economic meltdown and associated instability. Our economic house of cards must falter no matter what, but don't tell them that.

One other quick point. If some (non-existent) uber-authority decreed that global food production would stay constant at 1960 levels, then we would maintain 3 billion humans on the planet. The point is: it's a powerful, non-negotiable knob that we've historically only turned up in annual increments—predictably facilitating population growth.

As to your request for extinction references: an ugly compilation of links to DOI records:

http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0801918105

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/brv.12974

http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.1400253

http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature09678

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/brv.12816

http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.aau0191

http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1704949114

http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1922686117

Thanks for those links 🙂

This is a basic tenet of ecology, also known as "trophic excess enables fecundity". Look for the classic Lynx-Hare paper.

The problem (as always) is we humans seeing ourselves as apart from nature. If we view ourselves as just another species, all subject to the rules of ecology, it becomes much simpler to understand.

As to your counter-example of declining birth rates and projected (not actual) reduced global population, I have a theory, based on the work of the late ecologist Howard Odum, that excess non-trophic energy counters the typical reaction to increased food production.

If a new electric-powered well in a poor village means women don't need to breed a water-fetcher, the birth rate can go down. If a pension means women don't need to breed a retirement plan, the birth rate can go down.

This raises a disturbing possibility.

As fossil sunlight goes into permanent, irrevocable decline, women will once again need to breed a slave labour force and retirement plan. I predict that fecundity will actually increase, perhaps more than offset by increased death of children under five.

On population…….

Quinn talks about first nation Americans having to keep their populations in check because expansion into a neighbour's territory wasn't an option.

Does anyone know how this was achieved? Infanticide?

I can remember watching an episode of Bush Tucker Man in the 1970's.

He was in northern Queensland with an aboriginal community.

There was a certain berry that when eaten would induce a miscarriage.

But not all the berries!!!!!!

The berries were dropped in water. The ones that floated were good to induce a miscarriage. The ones that sank would kill you!!!!

(Or was it the other way round 🤷🤔😲?)

That's a, hard come by knowledge!!!!!

I'm not sure what practices were employed by Native Americans (does anyone know?), but Jared Diamond wrote about Tikopia in Collapse. They used a variety of methods, to greater or lesser degrees:

1. coitus interruptus

2. abortion

3. infanticide

4. celebacy

5. suicide (sometimes swimming out to sea)

6. virtual suicide (young men set off in boats never to be seen again)

7. (rare) warfare

When Christian missionaries arrived, they said "Oh, no, no, NO, that's shameful, sinful, abhorrent behavior." Once "set to rights" by the Christians, the island suffered a population explosion, ecological collapse, and many had to be moved off-island. Thousands of years of population stability was shattered in mere decades. I say: who are we (Takers) to judge something that worked well for those people. It wasn't imposed, but agreed as the proper way to live in accord with a finite ecology.

A fascinating read is "Just Enough", by Azby Brown.

Brown describes an extended period of about 200 years — the Edo Period in Japan — when famine was averted, and the population was fairly stable.

He alternates narrative fictional chapters with more expository prose. The family he follows are poor rice farmers, with just two children. He notes that the midwife "sent back" several pregnancies that would result in children they would not be able to feed.

I've read Just Enough and can recommend it.

Just one caveat, Edo Japan was a very structured society with little personal freedom and lots of State Violence " to keep everything in check.

Just a reflexion on the effects of the expanded (human) food production. It was said that it does not need to increase the population numbers and examples were given that in the wealthy parts of the world birth rates go down. I just thought "what about weight" and found statistics on obesity that says that in the wealthier parts of the world obesity increases.

Thus instead of increasing the human body mass by population numbers (as in the poor world) the excess food production (in wealthier countries) increases the average weight of the population.

I suspect that doesn't quite correllate, but it's an interesting thought. It seems obvious to me that increased food production, beyond a certain point, doesn't equate to increasing population. In the same way that increased energy invested doesn't equate to increased energy return, or increased volume of mining doesn't equate to increased volume of copper (or whatever). At a particular point, the resource is exhausted, and whilst the volume may appear the same, the quality becomes the deciding factor. Not all calories are equal. As the nutritional value of the food declines, then the various blocks of life, as a whole, become less viable. People have less virulity, less sperm, less fertility and so on. The available nutrition gets spread ever thinner across the populace.

Basically, what I'm arguing is that it isn't food that is the driver of population growth, but nutritious food. Could it be possible that we in the West – as an average population – have reached peak nutrition?

I think ultra processed food are the big culprit for obesity in the West. UPF with poor nutrient content. People eat more because their bodies aren't getting the nutritions they need.

It's a vicious cycle.

That's not due to over production of food but market forces, value added and increased profits for food processors/manufacturers

Probably an eighth measure of population control was leaving disabled babies out in the bush to be eaten by the wildlife.

I recall a FB video years ago that went a bit viral, showing a stork throwing out of its nest a several week old chick, because it knew the carrying capacity of its region wasn't up to the number of chicks that had been born that year.

As regards food increasing babies –

It's basic evolutionary process – any species will fill out an environmental space to the maximum of its ability, the limit being the carrying capacity. See the work of Dr William Rees (many videos on YT).

You could try an experiment to test the thesis. Whatever back yard or garden you have, will have a set number of rats either living in or nearby. You'll rarely see them. But if you start leaving out food scraps in the middle of that yard every other day, within 12 weeks your neighbours will be complaining about the number of rats they have seen, and you might trip over some yourself. In other words, you have increased (however temporarily) the carrying capacity of that space.

Another example is my front yard. Fronts on to a main road, and is paved all around. I have pots with lots of wild flowers/plants in, including red campion. Every year the red campion sets a few more seeds successfully, and more plants appear in other pots. Every year, each stalk of the red campion is covered in aphids. It must be symbiotic relationship because the plant comes to no harm. Within a few weeks, the aphids are eaten by visiting ladybirds. So in a natural process, the red campion is spreading slowly towards its carrying capacity (the number of soil spots vacant in the top of the pots) and the number of aphids increases each year (as its carrying capacity is increased by the increasing number of rad campion stalks). I would post a photo if I could.

So yes, increasing the food supply does increase the number of babies. The bulk of the population don't see it because all they see is packaged food in the stores, we disguise the increased carrying capacity behind the complexity of the international supply chain. If everyone grew and/or collected their own food, we'd certainly know about it.

After reading this, I happened to listen to the recent address of renowned economist Prof. Jeffrey Sachs to the European Parliament, where Malthus also got a mention. You might care to listen to the last few minutes from 1:26:20 onwards (https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=u4c-YRPXDoM).

“As an economist, I can tell you we have plenty on the planet for everybody’s development, plenty”.

Like many, Sachs appears to have faith in technology to solve all our problems and thinks that the only major thing standing in the way is human conflict. With technology and peace, he says, “we could transform the planet, we could protect the climate system, we could protect biodiversity” etc.

I truly marvel at how people can look at a population surge graph like the one above, as well as data on extinction rates etc., and be so optimistic about the future. The idea seems to be that we’ll level off around 10 billion, pull everyone up to a decent standard of modern living, and technology will magically reduce our collective footprint and make it all sustainable, job done. It all just seems like such magical thinking to me. I’ll admit that I have never been the most optimistic person, but still…

(I have heard some people gleefully proclaim that Malthus was wrong because food supply can increase exponentially, not just linearly. All my worries for nothing then…)

Agreed. I've known enough "geniuses" like Sachs to have a sense for how they can look at a stunning graph like the population explosion and say: marvelous. It's, in part, a kind of showing off. "Smaller minds may cower in fright over what this means, and without brainpower of my caliber I can see why the wittle peepel wood bee scared. But I am undaunted. No: this is fantastic news—exactly as it should be. Oh what a pity that you cannot see its magnificence as I can." Their Jedi mind tricks aren't effectivce on me. I just hear pathetic insecurity, and they have no idea how transparent their chest-thumping adolescent displays of greatness come across.

In any case, it's heady stuff to imagine riding the dragon. To me, it's a fascinating example of how one of the meat-brain limits is a failure to acknowledge limits. Imagination is decontextualized and unconstrained, so can fly off into untethered territory in an instant. And our brains are too limited to tell us when we've crossed the line. So we befriend the dragon and become its master. More realistically, we're charred. Even more realistically, there are no dragons.

"So we befriend the dragon and become its master. More realistically, we're charred. Even more realistically, there are no dragons."

Well put🤣

I'm a simple person, new to this blog (thank you for it) and I'm struggling to understand it all and come to terms with it all. My first question is: at the level of the individual, what you/Ishmael are advocating is to become a Leaver? That may seem like a stupid question, because of course you are, but aren't you also trying to 'prevent the inevitable', at the level of the species, by trying to 'change the story' in as many people's heads as you can (including in mine)? Is it a part of being a Leaver to tell (true) stories and help people? I am struggling with this.

Thanks for asking! I guess I seldom explicitly lay it out. I would not say that I am advocating individuals to become Leavers. I don't see how that could work. I'll almost certainly never be disconnected from modernity. But I won't be around forever. The shift is mostly going to happen over generations and even centuries. What I can do is help give that future the best possible chance by getting folks to fall out of love with modernity, begin to appreciate the virtues of other ways of living, and promote the associated values and elements so that work on an off-ramp is begun. In that regard, I am definitely trying to change the story: offer an alternate that may have deep appeal for some. Perhaps most alive today will reject it entirely, but this is about planting seeds that might grow into something much later.

As for Leavers telling true stories, I would say that Leavers tell adaptive stories. As Vanessa Andreotti puts it, stories that "move" something good. If a story helps us live in long-term "right relationship" with the community of life, then there is deep truth to it, even if seeming silly, flippant, whimsical, fantasy, fabrication in a literal sense (i.e., factually untrue). Modernity has trained us to only appreciate literal truth, but that's a shallow skim on valuable, deep truth.

I struggle with it myself, and, like Alan in the book, can't yet see the light. That said, the other day, prompted by the book of Quinn and this blog, I contemplated on the kind of 'trait-salad' that could be some indication for either a 'Leaver' or someone tending that way. May be being as much desireless as circumstances permit? (it should not mean the lack of passion, but could need quite frequent mediation that is not easy to fit in a busy schedule. one the other hand, there are lots of folks passionate about frequent meditation, already). Might a good helping of a stoic disposition pave the way? (sparing energies, attention and worries to spend them across the scope of actions where one can truly make a positive difference or cause least harm to a broader community of life.) And maybe a good helping of 'wu-wei'? At any rate, I found two thought-provoking examples that may illustrate these in practice; one more active, the other more observant: (i) legend has it that a Chinese master butcher so perfected cutting through the fibers of meat and sinew that he never needed to replace and even sharpen his knife, while using the least amount of cuts; (ii) a known nature-builder, only by replacing small stones in the path of a thin stream, is able to spread it so wide and shallow that downstream the otherwise parched mountainside can grow greener and lusher, year after year.

This is a correspondence between Lance Pierce and Daniel Quinn (link below) where Daniel draws the answer to "What does it means to be a Leaver" out of Lance like Ishmael does with Alan.

http://web.archive.org/web/20030422075517/http://www.mshadow.com/illusions/vol1pp6.htm

Scroll down until you get to the section titled "COMPREHENSION BY CRUCIBLE By Lance Pierce."

Quinn basically refuses to give a straightforward answer, and Lance continues to fumble—until he finally gets it. It's a great read.

'The shift is mostly going to happen over generations and even centuries.' Can you reassure me that I've got this very broad-brush calculation wrong: Based on the following assumptions: 1) Carrying capacity of planet is 2 billion; 2) Carrying capacity was reached in 1975; 3) Peak population in 2040; and 4) the shape of the human population graph going up will be mirrored by the shape going down. Therefore human population will drop at a rate of !% per year – 100 million people per year! – reaching 2 billion again in 2105? Please tell me I'm wrong. I'm sorry I'm so behind the curve on all this. Honestly, I'm in shock.

First, my heart goes out to you for being in shock. On the one hand, I wish more people were capable of absorbing a shocking new perspective, so applaud you for making space for it and making an honest effort to come to terms. On the other, it's very hard, can be isolating, and can have disruptive effects. I struggled with this as a teacher: am I doing the students a great service or great disservice by sharing my awareness?

My only quibble with your math (given assumptions) is that a constant 100M/yr is not a constant 1% decline. At the end, 100M out of 2B is 5%. So to get to 2B by 2105 would require an *accelerating* rate of decline. If *truly* symmetric (where growth rate peaked around 2% in 1960), we would just have to ask when we were at 2 billion in the past, and mirror that result around the peak date. We hit 2B in 1927, so reflected around 2040 would be around 2150. We hit 1B in 1804, which would mirror to 2276.

But there is no reason to expect symmetry. My cohort-based model (see Peak Population Projections post) could have us at 4B by 2100 (actually not far from mirror of 4B in 1974), but this is without any drama: just fertility decline and demographic inertia. Add economic upheaval (almost guaranteed in decline scenario), war, disease, ecological breaking-points, climate change trauma, and the drop could certainly become more precipitous, and indeed achieve something like the accelerating decline of your 100M/yr model. Except it won't be smooth like that…

Thank you.

Though I've never read the actual bonus material since my copies are older versions, that Quinn's main modification to the anniversary edition was to focus on the population topic backs up my own experience in discussing the book with others – that it really hits a nerve. I never thought about "we're better than animals" being one of the reasons, but it makes sense. My suspicion was that it shakes up the whole moral foundation of First Worlders, and that people fight the idea tooth-and-nail because they don't *want* it to be true and thus will find any way to discredit it, or simply dismiss it outright. I grew up in the US in the 80s/90s, the era of "We Are The World", with Sally Struthers imploring you for "pennies-a-day" over footage of emaciated African children every commercial break and my older relatives bringing up the Ethiopian famine (or the Great Depression) if any bite of food was ever left on a plate. Facing the reality that not only did that not solve anything but led to…millions more starving children and the civil wars and atrocities we see today, situations where what little wildlife remains is being killed and eaten in response to famine, is difficult for people to face, to say the least. You could say, back then we got the glory for deciding who lives (which was everyone, even if their living conditions are absolutely miserable and desperate) and now that we have to decide who dies, we don't like the responsibility so much.

That being said, any time I come across a news article comments section on any environmental issue these days, people are not shying away from saying "global south overpopulation is the problem", but inevitably someone else chimes in with "no, global north overconsumption"…as if they aren't both ecological issues and causes of destruction and mass extinction. Only once or twice have I seen the dots connected to agriculture and food overproduction. But it's hard to argue about the massive consumption of resources and nonhuman life resulting from the average American lifestyle vs. say, average Guatemalan or Congolese, and I think it would have helped Quinn's case if he had discussed this a bit more as well. It does seem easier for some denizens of the global north who, through no merit of their own, have never known a day without access to food and likely never will, to discuss starvation in faraway lands; would they be singing a different tune if it was them, their family, their community? It's not like the hunger/population control is distributed in any kind of equitable way (though all the previous comments about nutrition/food quality/obesity, and I'll add chronic illness, got me thinking that there sure are other consequences in countries like the US).

Ultimately, though, it might all be a moot point – I agree with what you said in the Ch. 8 summary, that it is not likely we'll ever stop increasing food production. At some point we won't be able to, and then we will finally get our answer once and for all that food makes babies. I imagine Quinn will be vindicated.

Great reflections. The topic definitely hits a nerve. Quinn returns to it multiple times in The Story of B. I just finished drafting a monster post reviewing The Story of B (coming soon). That, plus comments on my Ishmael posts have inspired me to write a dedicated post on the "food makes babies" theme. Two related confounders are: 1) affluent nations have sufficient access to food yet are not hotbeds of population growth; 2) over 2/3 of the world population are in countries whose fertility is now sub-replacement—and those countries tend to have no food access restrictions. These (recent) nuances don't invalidate the mechanism that has been dominant for millennia. It is also worth asking if people would be okay deliberately stopping increases of food production. Fascinating to plumb the depths of that response!

I'll also mention that chapter 3 of my textbook emphasized that population growth in affluent countries is actually having more impact on the world than population growth in Africa. Consumption adds a hugely important layer to the otherwise one-dimensional growth rate figures. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9js5291m#chapter.3

I was hoping that you might have "done the math" around that! I'm diving into the textbook chapter now, and looking forward to reading the future posts.

Just be aware that when I wrote the textbook I had not done any "cohort tracking" math yet, so if I wrote the chapter today it would have a completely different vibe (as in my Peak Population Projections post and associated video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4-G70C90aas)