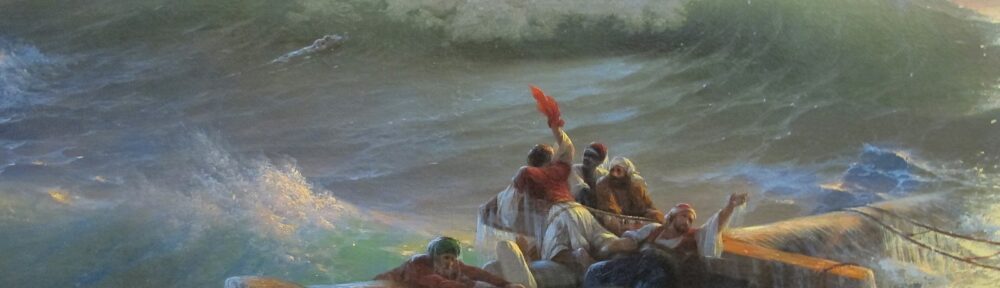

The mental image is easy to form: it’s just after first light on a morning in 1800 and your wooden ship has sunk after a surprise attack by canon fire. Random bits of wood and spars bob here and there on the waves, and you’ve managed to scramble atop the largest one. The next thing you notice is a horde of rats desperately treading water and aiming for your floating safety—as if vacuuming them from the surface of the sea. Within minutes your haven is teeming with clinging rats. Aside from the rapidly-receding gunboat, the horizon is clear of any other escape from immersion. It’s just you and the rats.

Why bother to describe this scene? It will serve a dual purpose. First, it vaguely mirrors a false impression many have of modernity as the only safe way to live in a perilous world. Second, it serves as an instructive contrast to actual encounters between modernity and tribal people. Both highlight the severe misimpression we have been handed of life outside modernity.

The Terror

Modernity relies on controlling food via agriculture, controlling “pests,” eliminating dangerous animals, controlling the spaces in which we live, controlling domesticated animals, and controlling other people’s actions via money and laws (carrots and sticks). We’re control freaks, one might say—seeking control over an ever-expanding set of concerns.

This approach to life shelters its participants to the point that they are robbed of the sort of freedom every wild being knows. Importantly, inability to secure satisfying wild food without much effort makes us daily-dependent on “the system” in order to get fed. Talk about control!

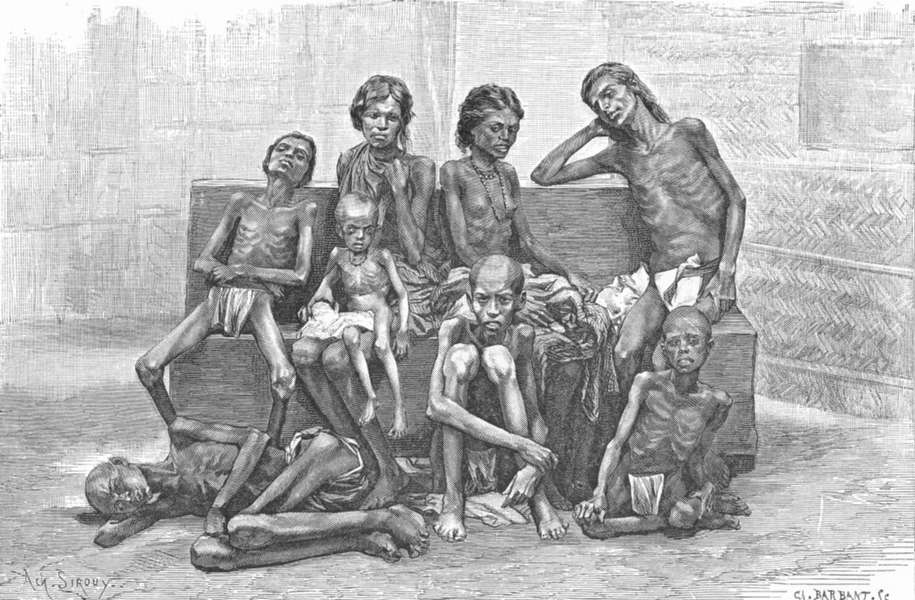

From the vantage of this enfeebled, helpless state of domesticated captivity, it seems inconceivable that one could enjoy life or even simply survive without the support of modernity. People really freak out at the suggestion that modernity must collapse one way or another, and that we need to find other ways to live. It seems as hopeless as standing on flotsam without any other dry option in sight. Leaving modernity surely means an unpleasant death. It’s the nihilism of ignorance: the conviction that nothing else (worthwhile) exists. Television “reality” shows are set up to have us gawk at how essentially-impossible life is when stripped of our comforts. We tell stories about how we saved ourselves from a life of misery and terror—how we struggled to reach the safety of our hunk of flotation. That our “system” is initiating a sixth mass extinction makes us feel all the more hopeless: between a rock and a hard place.

The terror “out there” is a very common perception. Probably 95% of the time anyone invokes the Hobbesian line that life before modernity was “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short,” or Tennyson’s characterization of nature as being “red in tooth and claw,” it is in affirmation of these sentiments rather than dismissing them as terrified ignorance.

First, humans outside modernity are definitely not solitary! They are not poor, being the “original affluent society“—obtaining all they need on part-time “work.” They spend lots of time singing, dancing, teasing, laughing, and relaxing—which sounds opposite of nasty. While they might, out of necessity, be aggressive toward intruders and sometimes make shows of strength to neighbors, daily life—the vast majority of lived moments—is cooperative and not brutish. Life spans are not as long as by modern standards, but once making it to ten years old, a reasonably long life becomes quite likely and normal. Old people are not rare. Simple math involving reproductive ages and child-bearing capacity indicates it could not possibly have been any other way. It’s more than speculation or storytelling. As an aside, I am well aware that saying even one positive thing about hunter-gatherer lifestyles brings charges of romanticizing “noble savages.” I recommend ignoring this defensive overreaction.

But on the subject of danger: does nature contain teeth and claws, sometimes colored by blood? Most assuredly, it does. Every effective lie contains a healthy dose of truth. Outside modernity, is puncture of a given human individual’s skin by such implements a daily, weekly, monthly, annual, or even every-decade experience? We would not be here if that were so.

Modernity barricades us in a bristling fortress set against the wildness outside. From this position of retreat, having disengaged from the external reality for generation upon generation, we tell spooky stories about what’s out there and shudder to think about the certain death of leaving our safe haven: thus the analogy to standing on flotsam in an otherwise empty sea. We either cling to our safety or face a cold, wet, hopeless, and short existence—cloudy and wet with a chance of sharks.

We Will Not Be Rats

This heading borrows from the title of a book I am enjoying presently called (in the U.S.) We Will Be Jaguars, by Nemonte Nenquimo and Mitch Anderson.

So, here we are in our well-provisioned floating fortress-of modernity, and we have figured out how to make smaller fortified boats so that we can travel into the wild world while clinging to our protective gear (this is essentially what I do when I go backpacking like the pathetic modernity wimp I am). Sometimes—and rather frequently in “explorer” days—these offshoot boats would encounter “wild” humans.

The fascinating observation is what didn’t happen in these encounters—time and time again. The “natives” did not swarm to the lifeboat like rats to flotsam (spoiler hint: they aren’t like rats). They did not say: “Finally, we are saved from our solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, short lives. Finally, we have real food obtained from the sweat of someone’s brow. Finally, we have protection from the nightmares in the dark. Finally, we have proper shelters and apparel. Finally, we can be truly human.”

No: most perplexingly, such reactions kept not happening. What the free people did do—time and time again—was fight like hell to keep their beloved way of life. Instead of rats desperate to be saved, they fled our boats and shot arrows back at us. Those two scenarios look remarkably different, don’t they? How could we have gotten so confused?

Rationalization

The typical response is that: “The savages were just ignorant. They had no idea what they were missing. The poor beings were too dumb to recognize that they were running from a glorious lifestyle—one that offers money!” But this is completely incompatible with the simultaneous conviction that native life was miserable, terrifying, and desperate. Miserable, terrified, desperate people will gladly accept help and jump to safety and comfort—or be too weak to resist help.

To give one’s life in order to preserve a lifestyle speaks volumes to the merits of that lifestyle. Moreover, the very fact that such people possessed the strength, capacity, and determination to sustain stiff resistance says that they were less than desperate: they were healthy and well-fed. They correctly assessed that by far the biggest dangers in their lives were not teeth or claws of any color, but bullets, money, and property rights. BY FAR!

Also running counter to the “ignorance” charge, those Europeans who meaningfully integrated into Native American culture tended to choose staying in that culture, when still possible in the wake of surrounding genocide. Native Americans who had a taste of modernity tended to go back when they could, but this was seldom realistic given the obliteration of their cultural ways and communities. Full, adult exposure to two markedly-different lifestyles cannot be called ignorance.

Ironically, in 1651 when Hobbes offered his nasty nugget, many people around him were living lives far more poor, nasty, brutish, and short than those who never had the pleasure of modernity’s acquaintance. Returning to “reality” television, shows like Alone betray their fundamental flaw right there in the title of the show! Banishment from a tribe (for being a narcissistic jerk, for instance) was essentially a death sentence. A severed finger is of no use without a hand. Similarly, the one season of the show I watched (on Great Slave Lake) imposed the additional constraint of strict boundaries that confined the solitary competitors to small patches of land. The hunted animals were not likewise artificially confined, nor are/were the Indigenous folks of that region.

A More Balanced View

The image of a lone safe haven on an empty sea—or a fort surrounded by howling dangerous chaos—is just wrong. What looks like shark-infested waters to our ignorant eyes (correct: I’m flipping who’s ignorant, here) that any sane rat would surely want to escape turns out to be a sea of waving grass providing innumerable accommodations and food opportunities for the rats. Actually, the rat analogy is terribly off because it suggests those happily living outside modernity are vermin—which I hope is obviously opposite my intent. It’s more a projection of how modernity views destitute people deprived of modernity’s graces.

Chapter 11 of Ishmael—and section 4 in particular—first offers a powerful image for how modern people perceive life outside modernity, and then a truly brilliant role-play dialog that exposes the disconnect rather well. I recommend taking a look, if you’re unfamiliar.

Very few modernist people have spent significant time embedded in hunter-gatherer bands, thus our collective egregious ignorance is completely understandable. But, those who have spent time report contentment rather than miserable suffering. Our reaction is usually something like: “That can’t be right; the anthropologist was clearly deluded.” Imagine the arrogance this requires: zero personal exposure outweighs decades of lived experience (witnessing millennia of successful tradition).

But, the main point of this post is that we don’t even have to trust the anthropologists. This simple pair of facts does most of the work for us:

- We in modernity are understandably frightened of a lifestyle with which we have zero personal experience—a lifestyle that we are assured is miserable and dangerous.

- The overwhelming Indigenous reaction to modernity was to fight and flee rather than scramble onto the lifeboat, clinging to relief from misery and terror.

There: I just saved you from decades of embedded living in order to realize that the ignorance is ours and that life outside modernity is not a living hell. Otherwise I would not marvel at and celebrate the chickadee chicks emerging from the nest with joy in my heart, but shake my head in tragic horror at the hellscape they are about to experience as they flit desperately from tree to tree, chittering in terror.

Views: 1289

Gracias por tu esfuerzo Tom. El párrafo que termina mofándose de la falsa sensación de control y evidenciando que por ella hemos perdido la libertad es para enmarcar.

Google translation: Thanks for your effort, Tom. The paragraph [This approach to life…] that ends by mocking the false sense of control and showing that we have lost our freedom because of it is worthy of framing.

Hi, what a good site. This commentary got me thinking.

The Architecture of Captivity

Modernity thrives on control—scientific, systemic, total. From farming to AI, we’ve built a world not of freedom, but of managed captivity. We regulate ecosystems, behaviors, even beliefs—then call it progress. But what if our dependence on these engineered systems is the real prison?

We fear collapse because we’ve internalized captivity as safety. Indigenous societies, often more connected and joyful, resisted this system. Our fear of “the wild” may be less about nature and more about our alienation from it.

Now, in trying to preserve democracy, we censor dissent, violate rights, and justify coercion. That’s not protection—it’s betrayal. You can’t save freedom by destroying it. Maybe it’s time to stop optimizing the zoo—and start questioning its walls.

I think it might be the comparison with modernity that would put a hunter-gatherer existence as terrible. It seems doubtful that most people could change to that way of life, survive, and be happy. And disease or injury would be a death blow for many. Personally, it sounds like a much better way of life than what we have now but almost impossible to transition to. However, it's an impossible way of life for 8 billion people, but some much smaller human population will have to make that transition at some unspecified time in the future. It''s the only potentially sustainable way of life.

Yes, modernity often acts as a one-way trap door: develop dependencies while removing/eliminating the basis for survival in the old ways. For example, replacing a forest with fields eliminates the possibility of reversion. And I agree that 8 billion people cannot live ecologically on the planet. It's probably nowhere close to that. If we're lucky, natural demographic down-shifting can get us there over time: not by next week.

Could demographic down-shifting and luck be sufficient to reach a new population equilibrium?

While the demographic fertility declines are certainly fascinating and relevant, and may be providing some measure of pressure relief, the fact that we have gone so far into overshoot makes me think that the negative feedback corrections of dominating positive exponentials are very unlikely to be painless. I expect something more like massive famines, given our unsustainable agricultural system, and the timelines.

To quote Gandalf, "There are things set in motion that cannot be undone." Am I being too pessimistic?

Tom – When you say nowhere near 8 billion, I wondered whether you had any more definite idea of what the that human population might be. As far as I can gather, the pre-agricultural population was under 10 million, ie. about 3 orders of magnitude less than our current numbers. Given that hunter-gathers were (presumably) well adapted to their environments and had ample time to fill available niches and reach equilibrium, is there any reason to believe that post-agro-technological humanity could carry on at higher numbers? (If anything, given the environmental degradation which we have inflicted, one might expect the planet to have a lower carrying capacity). Do you foresee current demographic trends gently gliding to that sort of level? Put differently, are the mechanisms which would produce a 99.9% population reduction different from those leading to a 100% one.

Your basic reasoning agrees with my own: the experiment has already been run and optimized, so we have a highly relevant data point: 10 million. That's no guarantee that post-modernity human population will settle out to a similar number. It could be lower (down to zero) as a result of the inflicted damages, or higher because we lock in some learning from the modernity experience, adapted to an ecologically-integrated, sustainable mode. I would be foolish to stick to a number, but have doubts it could stabilize over 100 million in the long haul.

As for how we get there, I have no idea. Because the current global connectedness will erode in the process, the situation may fragment into many different trajectories spanning smooth to horrific. Or the same region could experience bits of both, and everything in between. In other words: probably not one monolithic story. Unplanned demographic decline would help, of course, but it seems fantastical to believe that major disruption and suffering can be avoided altogether, in all places and times.

You really do need to start reading Murray Bookchin's work, he was writing about this in the 1980s and his political theories would interest you greatly, they reject the hierarchical exploitation of modernity in favour of an ecologically rooted socialism that strives to live in harmony with the ecosystem rather than seek to extract "value" from it.

I tried to read Bookchin's Ecology of Freedom, but was frustrated with its presentation, which seemed unnecessarily convoluted and "scholarly." If I worked hard, I could distill many pages into a sentence or two, and wondered why the author hadn't attempted the same. I suppose the result might not have been book-length. In my own academic tradition, the goal is to be as precise and succinct as is possible. The subject matter can be hard enough to understand, so the aim of text is to maximize clarity without sacrificing accuracy. I didn't get that vibe from Bookchin, which could be due to my own inadequacy.

Nah, I felt the same, and I'm exceptionally smart*. Bookchin has some great things to say, just isn't great at saying them. If the solution to our predicament is cultural, which I believe it is, then the message needs to be simple and understandable, and I don't think Bookchin understood that (or perhaps his ego got in the way, and he strived to be smart). I also didn't think he was describing socialism, rather anarchism, but I could be wrong – it's been a while since I've read anything of his.

*This was an attempt at humour.

FWIW, I did laugh at what struck me as an obvious jest. Yes: Bookchin was more in the anarchist stream (which is appropriate in small-band arrangements). It would be nice if someone has boiled down his work to a few pages. Maybe they have, but I never looked.

Predicaments have no solution, only outcomes. The outcome, in this case, can't include the continuation of modernity.

some thoughts:

If we have evolved coherently with other species, then we must have our own niche (or way of life) that is compatible with all other species (to some extent) and our own survival, then we must understand and start moving towards it. This ecological role, of course, is not static but dynamic. But the point is, hunter-gatherers did not brush their teeth, did not perform complex surgeries and did not adhere to a refined diet and still managed to survive to this day. They did not need writing and reading, and some (for example, the Yagans) possessed incomprehensible physical qualities (withstood temperatures down to -12°C almost without protection) or cognitive abilities (verbal maps, complex modeling in the "head", etc.).

How can we be smugly proud of modernity, when on an individual level each of us is a helpless, unadapted, worthless person who will die of sepsis without a toothbrush? xD

Have you ever read Civilized to Death by Christopher Ryan? I highly recommend the book which is about the same subject of this article. I love subversive books like Ishmael and Civilized to Death. I recently had my 16-year-old daughter watch "Into the wild" which really shows how much joy you can have when you drop out of society and stop living in fear. It's the fear that keeps us trapped. Tom, thank you so much for what you do! I hope you know how much people appreciate your writing and willingness to take stand!

I am not familiar with Civilized to Death, but will check it out. Into the Wild has got to be in my top 10 list of movies. The relationships Chris forms along the way are amazing, and have a genuine quality to them. Episode 9 of Human Nature Odyssey centers on this story and is worth a listen: https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/human-nature-odyssey/id1682310706

I have heard of that book but I haven't read it.

Thank you Tom.

Learned of this post from Resillience.org rebroadcast. Well said. Look forward to reading your other posts.

The hunter gather way of life is terrifying to us "Modenistas" because we wouldn't survive. We no longer have the requisite skills.

I wonder how far back in my "family tree" I would need to go to get to a hunter gatherer?🤔

It isn't really anyone's fault that us "Takers", see "Leaver" lifestyles/culture as scary.

We are born into a time/place/culture not of our choosing.

This is close enough to a comment by Joe Clarkson on Resilience (same post) that I copy my response here:

I continually fail to anticipate readers' tendency to interpret perspectives on hunter-gatherer ways as suggesting personal transformation into that mode, or a shift of 8 billion people. That's essentially impossible, for reasons you point out: I can't do it.

For me, the point is to appreciate the mistake of modernity so we can take our feet off the accelerator and allow coasting to a stop—which may take many generations. Alternatively, we could maintain our commitment to modernity, slam into the wall (finish setting the stage for a sixth mass extinction), and all be the worse for it, down the road.

If we're scared of even the *concept* of living outside modernity, we will attach existential priority to its preservation, rather than the (ultimately) healthier act of letting go. In other words, don't be scared on behalf of our great-great-grandchildren just because we ourselves couldn't hack it, and as a result try to "save" them from that way of life. If this post helps some be less frightened (for other than themselves), then the effort will have been worth it to me.

Tom, that final paragraph nails it for me. I think you should have included it in the article!

Alas, I'm not exceptionally smart! 😉

I am doubtful people who are imbedded in modernity (almost everyone, even if their modernity is primitive compared to others') will ever be comfortable with the prospect of a return to a hunter-gatherer existence. Personally, I think such a return would be preferable to this way of life but I am no less frightened by the prospect than I was before I started to consider this subject.

All humans were hunter-gatherers at some point in the recent past. But that way of life didn't persist, for a reason. Though the means to forego that way of life will not be as readily accessible in the future, I have no doubt that humans' inevitable return to hunter-gathering will eventually develop pockets of civilisation in the future, assuming humans remain extant long enough.

@tmurphy

"so we can take our feet off the accelerator and allow coasting to a stop"

I understand the sentiment but am not sure what you mean by "coasting to a stop"?

I mean stop doubling down to keep the elements of modernity in full swing. Don't try to reverse fertility decline. Don't try to save failing institutions. Let modernity dissolve. It's a hospice mentality, not breathing machines and dialysis and radiation and chemo and all that.

Modernity ends when the availability of cheap abundant energy comes to an end.

There is no "feet on the accelerator". It's all material after all.🙂

Science has material limits. Without cheap available energy to create the machines to test theory, science grinds to a halt.

@tmurphy

"In other words, don't be scared on behalf of our great-great-grandchildren"

But I think the point is that……. For Modernity to end, the vast majority of us 8 billion souls aren't going to have any great-great grand children.

There's a "bottleneck" on the horizon. The vast majority of us are going to be evolutionary "dead ends".

We're given the impression within modernity that all species evolved to adapt to their environment—except humans, who, somehow, evolved entirely in "the wild" WITHOUT adapting to live well in that environment. Evolution adapting us to be miserable makes no sense and is the exact opposite of what evolution does. It's baffling that this is the accepted impression.

Bingo! I happened to just be reviewing my draft post covering The Story of B, and this point rings clearly. Also, Ishmael Chapter 11 does a good job exposing the absurdity of this misimpression.

My partner has laid down the law to me. No more 'end of the world' talk, it's 'too depressing'. How can I raise awareness generally when I can't even talk about it to my partner? Talk about loneliness. I am grateful (understatement) for this blog!