Whenever I suggest that humans might be better off living in a mode much closer to our original ecological context as small-band immediate-return hunter-gatherers, some heads inevitably explode, inviting a torrent of pushback. I have learned from my own head-exploding experiences that the phenomenon traces to a condition of multiple immediate reactions stumbling over each other as they vie for expression at the same time. The neurological traffic jam leaves us speechless—or stammering—as our brain sorts out who goes first.

One of the most common reactions is that abandoning agriculture is tantamount to committing many billions of people to death, since the planet can’t support billions of hunter-gatherers—especially given the dire toll on ecological health already accumulated.

Such a reaction definitely contains elements of truth, but also a few unexamined assumptions. The outcome need not be reprehensible for several reasons.

We All Die

Presumably this doesn’t come as a shock to anyone, but the 8 billion humans now on the planet are all going to die: every last one of them. This will happen no matter what. It’s inevitable. No one lives forever, or even much beyond a century.

Are we mortified by this news, intellectually? Of course not: our individual mortality comes as no great surprise. Some even accept it emotionally! So, there we go: whatever (realistic) proposal anyone else might offer for how humanity goes forward has the exact same consequence: OMG: you’ve just committed 8 billion people to die! You decide to have toast for breakfast? 8 billion people will end up dying. Nice going. Monster.

Timescales

I suspect that many strongly-negative reactions to suggestions that we adopt a “primitive” (ecologically-rooted) lifestyle trace to an implicit assumption about timescales. Maybe this is a result of our culture’s short-term focus on quarterly profits, short election cycles, or any other political proposal that tends to promise short- or intermediate-term results. So, perhaps it is assumed without question or curiosity that I am talking about a radical transition taking place over years or decades rather than centuries or even millennia. I would never…

Maybe I need to be better about pre-loading my discussion with this temporal context, since the assumption of short-term focus is so universal, and I get accused of misanthropy for something I never said—a running theme in this post. Abandoning agriculture need not happen overnight (and can’t, reasonably)!

Hypocrite!

Some of the angrier reactions suggest I volunteer to be one of those killed dead as part of my assumed/conjured “program,” or that I get my hypocritical @$$ out into the woods to eat lichen, naked. First of all, normal attrition, accompanied by sub-replacement fertility, is all it takes to whittle human population down, without requiring even a single premature death. And suppressed fertility needn’t be programmatically mandated like it was in China for a few decades: it’s happening on its own volition right now, around the globe. Roughly 70% of humans on the planet live in countries whose fertility rate is below replacement. It’s not a niche phenomenon, and presages a nearly-inevitable population downturn once the already-rolling train reaches the reproductive station in a generation’s time.

Part of the “you first” reaction, I believe, relates to our culture’s emphasis on the individual self. People automatically translate that I am asking them, personally, to become a hunter-gatherer or die. Again, I never said that, but it’s not unusual for people conditioned by our culture to take things personally, given ample reinforcement that we are each the deserving center of our own universe and little else matters. It is therefore understandable that members of modernity would assume (project) the same outlook is true for me. For those operating under this narrow (self-referential) assumption of how all others work, many valuable voices in the world must become baffling—or suspected of being disingenuous—which is a little sad.

When I point my passion toward avoiding a sixth mass extinction (which I interpret to include humans), I am not thinking about myself at all, but humans not yet born and species I don’t even know exist. My concern is focused on the health and happiness of a biodiverse, ecologically rich future. I myself am practically a lost cause as a product of modernity still trapped within its prison bars, and sure to die well before any of this resolves. Moreover, I can’t decide to roam the local lands hunting and gathering as long as property rights prevail and I do not enjoy membership in an ecological community operating outside the law. But, what I can do is try to get more people to wish for freedom, so that when opportunities arise good things can germinate in the cracks and force the cracks wider—even if I’m long gone when the crumbling process is complete. To repeat: it’s not about me. Talk of hypocrisy misses the boat entirely, by decades or centuries.

Not Even a Choice

Even if my audience gets over the shocked misimpression that I’m not talking about them personally, or a transition in their lifetimes, the objection can still remain strong. Isn’t keeping something like 8 billion humans alive indefinitely (via replacement in a steady demographic) far superior to something like 10–100 million hunter-gatherers living in misery?

First, the Hobbesian fallacy of believing foraging life to be “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish and short” is so far off the mark and ignorantly uninformed as to be pitiable—but certainly understandable given our culture’s persistent programming on this point. Christopher Ryan’s Civilized to Death does a fantastic job dismantling this myth based on overwhelming anthropological evidence. Turns out we don’t get to fabricate stories of the past out of whole cloth (i.e., out of our meat-brains), without one bit of relevant knowledge or experience.

More broadly, if one’s worldview is that of a human supremacist (nearly universal in our culture, after all), then preservation of a ∼1010 human population makes complete sense: can’t have too much of a godly thing.

But we mustn’t forget that 8 billion humans are driving a sixth mass extinction, which leaves no room for even 10 humans if fully realized, let alone 1010. Deforestation, animal/plant population declines, and extinction rates are through the roof, along with a host of other existential perils. We have zero reason or evidence to believe (magically) that somehow 8 billion people could preserve modern living standards—reliant as they are on a steady flow of non-renewable extraction—while somehow not only arresting, but reversing the ominous ecological trends.

No serious, credible proposals to accomplish any such outcome are on the table: the play is to remain actively ignorant of the threat, facilitated by a narrow focus on this fleeting moment in time during which the modernity stunt has been performed. If ignorance did not prevail, we’d see retreat-oriented proposals coming out of our ears for how to mitigate/prevent the sixth mass extinction—but people say “the sixth what?” and go back to focusing on the Amazon that isn’t a dying rain forest. Most people know about climate change, but the dozens of “solutions” proposed to mitigate climate change amount to maintaining full power for modernity so that we motor-on at present course and speed under a different energy source. The IPCC never recommends orders-of-magnitude fewer humans or abandoning high-energy, high-resource-use lifestyles…because it would be political suicide—which says a lot about the limited value of such heavily-constrained institutions.

Saying that the planet (and humans as a part of it) would be better off with far fewer people can result in my being labeled a misanthrope, though I’ve never said I dislike people. I’ve heard it put nicely this way by several folks: I don’t hate people. I love them—just not all at the same time.

Quantitatively, 10–100 million humans on the planet for the next million years seems far preferable to 10 billion for only 100 or so more before the dominoes fall in a cascading ecological collapse at mass-extinction levels. Factoring in infant mortality and life expectancy among pre-historic people, a population of 10–100 million for a million years translates to roughly 200 billion to 2 trillion adults over time—far outweighing the total human life of 10 billion over a century or two.

Perhaps, then, I’m justified in turning the tables: reacting in horror to those who would propose to maintain a population of 8 billion, as this effectively condemns humans to a short tenure before mass extinction wipes us out. Why do proponents of maintaining present population levels hate humans so much? I’m actually serious!

Try this on: people love their kids, right? Let’s say that parents having 1–10 children are capable of expressing adequate love and providing adequate resources for all their kids. But if kids are so great, why not have 800 per family? You see, even great things cease to be great when the numbers are insane. 10–100 million humans can know a love and provision from Mother Earth that 8 billion surely will not. It’s madness, and our nurturing mother is being ravaged by the onslaught of the teeming, unloved—thus unloving—masses. Indeed, our culture wages war against the Community of Life, erroneously convinced that it was at war with us first. Yet, it created us, and nurtured us, or we would not be here!

Allowing normal demographic reduction to a sustainable population maximizes the total number of humans able to enjoy living on Earth. Now, I can’t really justify that as a valid metric—especially given our crimes against species—but I’m exposing my bias as a human (short of human supremacy: just expressing a preference that humans have some place on Earth rather than none). Not all human cultures have acted as destructively as ours, by a long shot, and many have considered Earth to be a generous, nurturing partner. Sustainable precedents liberally spread across a few million years at least somewhat justify the belief that humans can enjoy living on Earth without killing the host, and I’ll take what I can get.

Space Parallel

Tipped off by Rob Dietz of the Post Carbon Institute, I listened to a fantastic podcast episode called “The Green Cosmos: Gerard O’Neill’s Space Utopia”. In the last four minutes, professor of religion Mary-Jane Rubenstein reported that her students held an inverted sense of the impossible. To them, it was utterly impossible to imagine living on Earth with “nothing” (tech gadgets) as our ancestors actually really definitely did for millions of years, while not doubting the possibility that we could build space colonies in the asteroid belt and keep our devices and conveniences—despite nothing remotely of the sort ever being demonstrated. The delusion is fascinating, reminding me of Flat-Earthers, as featured in the insightful documentary “Behind the Curve.” Just as the earth looks flat to us on casual inspection, a few expensive stunts make it look to the faithful like we could someday colonize space. That’s right: I’m lumping space enthusiasts in with Flat-Earthers: enjoy each other’s company, folks!

But the base disconnect is very similar, here. Maintaining 8 billion human people on Earth is no more possible than invading space. It’s not an actual, realizable choice—beyond transitory and costly stunt demonstrations.

Hating the Likes?

The other head-exploding facet to the proposal of a much-reduced population living in something closer to our ecological context is that it would seem to amount to a callous repudiation of precious products of modernity: opera, symphony, great art, lunar landings, modern medicine, David Beckham’s right foot… Why do I hate these things? Well, I never said I did. Again with the words in my mouth… What I—or any of us—might like or dislike is completely irrelevant when it comes to biophysical reality and constraint.

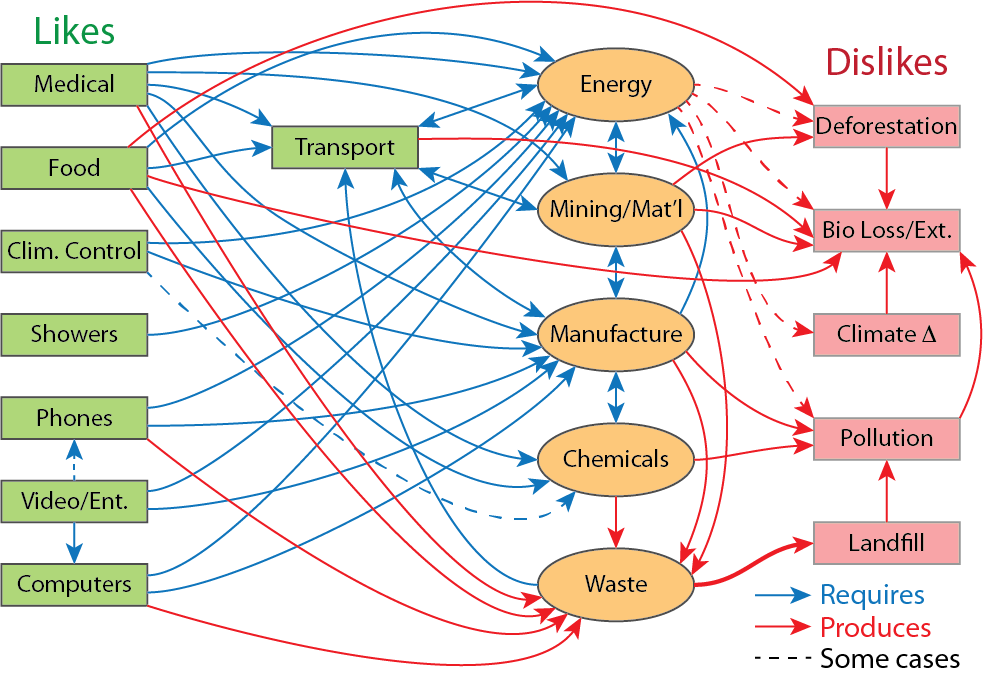

What makes us think we have a choice to separate the good from the bad, when they are most decidedly a package deal that we’ve been wholly unable to separate in practice, all this time? The following tangled figure—itself a staggering oversimplification of the actual mess—is repeated from an earlier post on Likes and Dislikes.

The fundamental flaw is that when faced with an unfamiliar landscape, our brains instantly and automatically assign separate qualities and features to a reality that in truth is inseparably inter-linked. Because the connections are numerous and often far from obvious, we are tricked into believing the entry-level mental model of separability. It’s the most basic and naïve (often adaptively useful) starting point to recognize a bunch of “things” without delving into the Gordian Knot of relationships. But that’s the easy part, and many stop there before it gets hard—often too hard for the very limited human brain, in fact. No blame, here: we all do it.

The Likes and Dislikes are a single phenomenon, having multiple interrelated aspects. Despite initial unexamined impressions, apparently we don’t actually get to choose to have modern medicine without advancing a sixth mass extinction. I’d give up a lot to prevent such a dire outcome—including modern medicine, since preserving it appears to translate to its own terminal diagnosis. Living seven decades is not rare in hunter-gatherer cultures; dental health is far better without agricultural products like grains and sugars dominating diets; and the chronic diseases we know too well in modernity are effectively absent for foraging folk (and not because lives are too short to expose them to the possibility—look deeper!). Modern medicine has extended adult life expectancy (once surviving infant mortality) maybe a decade or two, but at orders-of-magnitude greater per-capita ecological impact: a fatal “bargain” that calls to question our judgment.

Let the Standing Wave Stand

Some cloud patterns stay fixed relative to terrain—a coastline or mountain range/peak—even though the wind whisks along (see orographic and lenticular cloud formations). Moist air condenses at the leading edge, droplets careen through the formation, then evaporate on the trailing edge. These “standing wave” patterns are at once stationary and dynamic, with individual constituents playing a transitory role in a larger, more persistent phenomenon.

Human lives are similar: we flow into and out of life, while genetic patterns preserve a slowly-evolving human form across generations. The problem is that the magnitude and practices of the phenomenon are destroying the ecological conditions that allowed the phenomenon to arise and get so large in the first place. Our 8-billion-strong “cloud” is grossly unsustainable, so that it will collapse via its own downpour if not allowed to shrink. It’s possible to do so by natural attrition and generational transformation of lifestyles. While many factors threaten to make such a transition turbulent and “lossy,” the endpoint itself does not inherently demand a tortured path. Again, given modernity’s structural unsustainability, where we end up is not really an open choice. So, it’s best do what we can to make the only real positive outcome emerge as smoothly as it might: by embracing it and leaning into it rather than putting up a futile and destructive resistance that will hurt (all) lives far more than on the gentler path. Either way, 8 billion people will die. The bigger question is: will millions still live?

Views: 7023

I often think: In India, a billion people live on less than $10 a month.

It's shocking. This forced poverty is shocking. This is an incredible hidden demand for everything from transportation to diapers. This is hidden terawatts of energy…

These people don't live in a hunter-gatherer society, they live in capitalist slums in big cities, as scavengers and scavengers. Do any of the great economists, politicians and thinkers think about this when they call for doubling the human population for the sake of growth? I don't think so. The horrors of plague, smallpox and other diseases in the Middle Ages were already markers of unsustainable population growth and population density.

No, they don't.

I came away from an Energy Council (University-based, trans-discipline) seminar alongside a long-standing academic who is actually on the Council.

"…after all," I said, "energy underwrites money".

To which he – an economics/finance Professor, replied: "I've never thought of it that way".

I looked at the sky. How could he not? But he did – and they all do. It's amazing mental sleight-of-hand which I sometimes envy.

But then I don't. I have constructed a life which attempts to give-back to the biosphere, more-or-less within the rules of the present paradigm. It is actually a lot of fun, very rewarding/satisfying, and you go to sleep with an easy conscience.

If The Limits to Growth standard run continues to be approximately correct, I do think there will be a massive die-off of billions of people within this century, continuing into the next century. That population reduction would be mainly caused by increased mortality from famine, disease and wet bulb events. Even if we eventually end up with a small sustainable population of perfectly happy hunter-gatherers in a fully recovered environment, that's not much of a comfort to people who have to live through the collapse.

One thing to consider is that the environment our hunter-gatherer ancestors lived in simply does not exist anymore. The environment will eventually recover from all the ecological devastation but not necessarily within a timescale that is relevant to humans.

One of the most honest, thought provoking, and calm offerings/observations of our "8 billion" predicament I've read or encountered to date. Thank you, TM!

Awesome! But given the choice, I would prefer to die slowly.

If ignorance did not prevail…

My own latest read was Carl Sagan's 'Demon Haunted World', his observations were keen at the time, though the situation he describes has gotten much worse since the book was published (1995). People are not only drawn to many irrational and strange beliefs, the dominant (misguided) culture is inculcated into us since birth. There are extremely well funded and wide-reaching propaganda campaigns, disinformation, misinformation, algorithms, AI, bread and circus distractions, psychological impediments, and more. Add on a dismally bad education education system, a populus untrained in critical thinking, the opportunity costs of specialization (mental bandwidth, time, brain-shrinkage), and it should be no surprise that the cult of ignorance reigns supreme. Frankly, it is rare to find people bucking the default trends, which is why those who understand and care about the sixth mass extinction remain a small minority. Most people may eventually care, but not until it is on their doorstep and impacting them personally (probably when it's too late).

Describing modernity as a prison is apt when one considers how we are 'locked in' to the prevailing constructs causing the suicidal push for infinite growth on a finite planet. I can identify four legs to the stool, perhaps there are more. 1) The competitive nation-state system that results in multipolar traps like arms races, causing profligate energy waste to maintain militaries, which themselves want economies, infrastructure, populations, and industrial bandwidth behind them to be 'strong', to amplify their own strength. 2) The embedded growth obligation of the market to service debt and the constant push to grow the economy to avoid recession/contraction. 3) Consumption culture driven deep into the brains and lives of billions of people over decades. 4) Uncontrolled population growth.

I am happy to cheer on demographic downshifting relating to a potential reversal of the fourth item, though do not see evidence that any of the other drivers will stop, reverse course, or change substantially of their own volition before hitting the consequences of negative feedbacks. The fact that negative feedbacks are delayed and take some time to fully express relative to the point of overshoot violation creates an almost a trap-like situation by itself.

It seems that our collective overshoot situation is largely crystalized at this point. Business as usual appears to be slated to continue on with the momentum of a thousand freight trains until it goes off the tracks. Though I personally fail to envision any way that it will end up being a gentle trainwreck.

"People are not only drawn to many irrational and strange beliefs, the dominant (misguided) culture is inculcated into us since birth."

The process of inculcating the culture in which you are raised is called enculturation. As you say, it is a powerful force, especially as most of the work is done in the subconscious in the first few years of a child's life because of the hard-wiring for culture in the human brain. When you adapt to another culture in your later childhood or as an adult, this process is called acculturation and happens at the conscious level. It is more difficult BUT it can be done. This is the same process that one can use to acculturate to a much-reduced sustainable lifestyle.

Now consider why all the righwingers STILL hate us "dirty hippie commie pinkos." It is because smoking weed is an easy way to shift paradigms. This was not lost on us in the 1960s. Now the mainstream culture has decided to accept psychedelics in therapy since they think they can co-opt the consciousness-raising aspects so that the patient/informant/subject will remain in the dominant culture. I have to laugh at this oxymoronic view. [If you raise your consciousness, OF COURSE you will reject the culture that got you into this mess in the first place.]

Smoking weed and ingesting psychedelics was just the opening of the door. The next step of seeing "whose backs that strong" required a LOT of work. It still does, fifty-five years after the Grateful Dead made that comment in New Speedway Boogie (Workingman's Dead, 1970).

I remember David Suzuki pointing out how domesticated animals grow bigger, but remain in a lifelong state of social immaturity. Perhaps those who cling to hierarchies the most fiercely are the most domesticated and infantilized of the human animals.

Maybe modern consciousness raising merely approximates more closely the state of our ancestors, who had naturally larger brains. Often there are descriptions of 'oneness' or 'connectedness' with the universe associated with these substance-induced experiences, perhaps smaller plastic-filled brains need a 'boost' to achieve that frame of thinking.

"My concern is focused on the health and happiness of a biodiverse, ecologically rich future"

Why does this matter though? At some point the earth will be lifeless anyway. The universe won't care. Why is a planet with more species better than one with fewer or none?

To each their own, I guess. It's not an expression of pure logic or rationality. Something is more satisfying than nothing, to this being. Not caring is just not how I'm wired.

I am playing devil's advocate here and thinking on geological timescales….

You are lamenting the 6th mass extinction, but isn't it true that there is normally an evolutionary "explosion" follwing mass extinctions? In which case the future *will* be ecologically rich again (no matter what humans do)… so it seems you are exhibiting a time-preference bias and I have a sneaky suspicion that lurking there is some unrecognised anthropocentricism…

Yes. It may be without humans but, provided some life gets through the bottleneck, there will be a highly diverse biosphere again. This particular mix of species is no better or worse than any other mix of species that the Earth has hosted in the past or will host in the future.

I'm not completely indifferent, being of this age of peak biodiversity. I don't feel awkward wishing against what still may be an avoidable mass extinction. Lamenting the potential extinction of many millions of species whose blood is on our hands is, I hope, a smidge shy of anthropocentrism. On the other hand, neither do I give 0.00000% weight to the species I happen to be part of, and who are not manifestly bad news in every time and culture. Plenty of ground exists between logical extremes.

"what still may be an avoidable mass extinction"

Is it avoidable though? Or are we just following our evolutionary programming (because there is no free will… 😉 ) and using up the resources available like most other species do? ( To be clear: i don't wish for a 6th mass extinction either but struggle with the philosophy behind that)

We can't know how things will unfold. A near-term collapse of modernity simultaneously increases short-term pressure and decreases long-term pressure. Part of our evolutionary programming involves apprehending novel threats/stimuli and responding to them. That can actually mean prefrontal-cortex-driven restraint. Free will need not apply: we're either wired to respond appropriately (or just ride it out and hope luck is with us), or we're not. If 6ME awareness is made high and the strong response to that stimulus is to try avoiding it at all costs, who are we to rule out the possibility that things might go that way? I say: bring on the stimulus and let's see what happens. What else am I doing today?

Another related essay here from W. Rees. :

https://reeswilliame.substack.com/p/fatal-delusions-and-the-curse-of?utm_source=post-email-title&publication_id=3740437&post_id=174381923&utm_campaign=email-post-title&isFreemail=true&r=ba5a6&triedRedirect=true&utm_medium=email

Personally, I wish humans had never invented agriculture but I don't have illusions about a return to hunting and gathering (not that I'll have to do that personally, but you never know). As a description of "Civilized to Death" mentioned, "Prehistoric life, of course, was not without serious dangers and disadvantages. Many babies died in infancy. A broken bone, infected wound, snakebite, or difficult pregnancy could be life-threatening." I can't imagine many people, in that life-style, dying peacefully in their sleep, after a long fulfilling life.

I recall an episode of "The Ascent of Man" which looked at the Bakhtiari peoples of Iran. They were a nomadic herding people moving their herds around during the seasons. Old people who could no longer make the journey were eventually just left to fend for themselves, as the rest of the group moved on with their herds. Of course, this isn't necessarily what hunter-gatherers would do, but one wonders whether a similar logic would play out.

Still, I doubt anyone would choose a hunter-gatherer lifestyle in preference to having at least some of modernity's comforts around (nor is it possible for 8 billion), so there is no need to try to convince people of the benefits of a primitive lifestyle. It will be whatever it will be.

Thanks for the book recommendation, though. I've ordered it.

The planet would be better off without humans? Well, perhaps ask the planet. What does it say?

I don't quite get your apparent quantitative measurement of preference for the human population times longevity. I don't think there is any way to quantitatively measure that without first assuming that the product of total human life years is the determinant, though you later admitted that it is simply your preference. What does the planet think?

You made a great point about what humans would like is irrelevant if those likes go against physical reality. So many people seem to rail against those who project a collapse of modernity, because what about health care, roads and overseas holidays? Humans couldn't possibly live without those things, so they must continue. No; go ask the planet.

Sorry about the criticisms, that's just the way I am. I agree wholeheartedly with most of the post; you have a great way of breaking things down.

Agricultural systems will collapse in many countries in the coming decades according to this paper form Jem Bendell.

https://insight.cumbria.ac.uk/id/eprint/6927/1/Bendell_BeyondFedUp.pdf

I have linked to this paper before, I think.

They even give a nice little summary

In this chapter we have looked at the six hard trends that are already happening, and lead to food system breakdown:

1. We are hitting the biophysical limits of food production and could hit ‘peak food’ within one generation;

2. Our current food production systems are actively destroying the very resource base upon which they rely, so that the Earth’s capacity to produce food is going down, not up;

3. The majority of our food production and all its storage and distribution is critically dependent upon fossil fuels, not only making our food supply vulnerable to price and supply instability,

but also presenting us with an impossible choice between food security and reducing greenhouse gas emissions;

4. Climate change is already negatively impacting our food supply and will do so with increasing intensity as the Earth continues to warm and weather destabilises, further eroding our ability to produce food;

5. Despite these limits, we are locked into a trajectory of increasing food demand that cannot easily be reversed;

6. The prioritisation of economic efficiency and profit in world trade has undermined food sovereignty and the resilience of food production at multiple scales, making both production and distribution highly vulnerable to disruptive shocks.

Considered individually, each one of the hard trends presents a very significant challenge to global food security. Considered collectively and interdependently, it becomes clear we have created a predicament on a scale and depth unprecedented in modern history, and unprecedented for the sheer number of people who will be affected.

Due to these trends, we will see a major die off as Pirkko mentioned above. By 2100, the population maybe a half to a third of what it is today.

I lament the anguish my grandchildren will almost certainly traverse (if they are among the survivors). I also probably lament the almost inevitable loss of some of our culture, and science, and knowledge.

Sapience seems to have been an evolutionary progression – an inevitable one – but one which was always going to go one step too far. By the time the most-sapient species realises that it is overshot….. it's already overshot. Hard to imagine a double-jump bypassing that stage. And it hasn't.

My old man used to say that you'd expect half the people you meet, would be below average – but he opined that it was far worse than that..

My pick is that pockets of humanity will survive – flourish, even. For a long time they'll have a lot of material to cannibilise, so it won't be hunter-gatherer in the old sense. But they will have trouble hanging onto information, indeed the ones who do – probably writing-up recordings of water, soil ph, seasons, growth-rates etc. – will likely also be the best-led and the most successful.

I just want to push back slightly on this section:

"Living seven decades is not rare in hunter-gatherer cultures"

While your statement is fundamentally correct it does somewhat ignore the very high child mortality rates observed in such communities, and in my opinion the biggest single benefit of modern medicine has been the vast reduction of child mortality rates.

I've linked to this BBC article about the Tsimane people before, and it does illustrate the good health and long life expectancy but also includes this statement from one of the Tsimane:

"Counting on her fingers, one woman says sadly that she had six children, of which five died. Another says she had 12, of which four died – one more says she has nine children still alive, but another three died."

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/ceq55l2gdxxo

I do not disagree with your post but we do need to be aware of the realities awaiting us. Hopefully a focus on essential needs over conspicuous consumption will help address this.

Do chimpanzees think about healthcare? What about blue whales or elephants? How are humans different? Selection works on the whole system and on each individual. That's the price to pay for having big, wily balls of meat on your shoulders. And that's how it's always been, until recently.

You're right to point this out, but how many times have we read that "We've doubled our life-span in the past century!"? To say that "Living seven decades is not rare in hunter-gatherer cultures" is not factually false or even misleading. But the ubiquitous propaganda about massively extending life-span certainly is. What percentage of people think our ancestors were old by 30 and dead by 40? I'd bet it's over 90%.

"Ignore" is perhaps too strong a term for something acknowledged in the same paragraph as the quote you pulled. Yes: there was a steep price to maintaining stable populations, but also steep reward in doing so.

Try this: first-year mortality among chickadees is staggeringly high. It's a real problem. It's too high a price. What if we intervened with technology to render first-year chickadee mortality essentially a thing of the past. How wonderful! In fact, why stop at chickadees: baby sea turtles, mice, mosquitos… Except then populations would explode exponentially leading to a tangled set of ecological crashes and disasters too numerous (and non-obvious) to name. On second thought, such interventions destabilize what evolution has worked out in a full ecological context (a form of deep-time wisdom we utterly lack).

Why any species should deserve a get-out-of-mortaility-card-for-free is beyond me. Life is paid by death. Removing the child mortality piece for humans is unquestionably complicit in the 6ME story. Superficial benefits are not true benefits.

That childhood deaths were much more common in early hunter-gatherer communities is something to temper a more optimistic view of going back to those ways. However, humans are almost certain to go back to that way of life, if they don't become extinct, since that is probably the only sustainable way of life.

Future humans won't be able to take healthcare with them when they move back to the hunter-gatherer lifestyle, but may be able to take some of the knowledge that could help reduce suffering.

There are simpler cultures who practice such things as not naming a baby for the first ~10 days of life and giving them only a simple burial should they die during this time. A period of grace where there is an acceptance of nature's weeding out of unhealthy babies.

Or you can take the modern world, where we don't trust that nasty nature stuff, where interventions are insisted upon and unhealthy babies, sometimes with serious disabilities or debilitating conditions, are put into specialized environments, pricked with needles, attached to tubes, given medicine, surgeries, artificial life support, and forced to endure. Arguably there are some moral pitfalls on this side of the coin as well.

Great article, well said.

Modern medicine, along with the emergency services etc, has given people a safer, but much more constrained (and boring), existence. What's been lost outweighs all the protections of the state.

And humans' precious safety comes at direct cost to the rest of the living world. Yet they buy into it, indoctrinated from birth by the system, inexorably tightening its grip on the host (Earth).

A paradigm shift is needed, such that people understand how their humdrum lives kill the living world.

There've been a couple of comments ~ 'why does it matter – Earth will eventually be lifeless anyway?' etc.

It may not immediately matter to commenters, but it definitely does to the plants and animals being destroyed *now*. It matters to them, as people's own survival does *to them* (otherwise, why express fear of death by snakebite/wound infection etc?)

But the creatures can't avoid the explosives or the mining machines, diggers etc. If it were possible to ask them, I'm sure they would prefer not to be destroyed by machines. Therefore, the users of that technology bear responsibility. Unfortunately though, the machine operators (just like the vast majority of society) are indeed indoctrinated.

So any words drawing attention to the folly of modernity's endless conversion of life into products, buildings, waste etc are to be commended.

(The Sun is *predicted* to fry Earth, ok but – no one knows exactly how it will unfold. Eg, an interstellar body could disturb Earth's orbit, allowing life to continue for longer. Unlikely, but the future is not set.)

James, it is "sad" that modernity is destroying the current biodiverse life on planet earth. But that "sadness" is a human construct. To me, there is solace and wonder to be found in the evolutionary process and the fact that life will go on *and "flourish" again* long after humans are gone (with many new and amazing creatures to come). It will be different, but not better or worse than what we have now. If the 5th mass extinction hadn't happened, we wouldn't be having this debate…maybe some future species will look back and be "glad" that we caused the 6th ME?

(Also, before the earth fries in a couple of billion years the movement of tectonic plates (in only a few million years) will affect the global climate and reshape the biota on earth once again https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=HRVkB2daFjM). This is where I struggle with some of Tom's reasoning (which overall has helped me immensely with my own thinking): he states that humans aren't special and just another species (agreed), but then seems to hope that some humans survive. (Maybe I have that wrong Tom?). This is maybe where we differ. I dont *want* humans to suffer/disappear, but recognise that where we lose, some otger life form will gain eventually. If all life should be valued equally then shouldnt that also include "future life" (in whatever form it is) and the recognition that that is just as important as "current life"? Unless there is some sort of time discounting going on which is what I don't quite get.

The problem with my thinking is that you end up in a "nothing really matters" situation and that feels uncomfortable too…

I have no trouble squaring "humans aren't a superior species" and "I prefer humans to survive." I also prefer newts to survive. I like my biome-home better than I like the one 70 million years ago or the one 200 million years into the future, because I'm a part of it. It's a bias. Biases are fine. Most species show a bias for their own, and for the Community they live within and depend upon. Similarly, I can place higher value on *some* life rather than *no* life, even if entirely different from the slate we have today. However, I can still curse the 6ME machine that we drive, and advocate not advancing it further. Likewise, I find myself against nuclear annihilation, even if (different) life may again flourish in 200 million years. Call me crazy. Otherwise you're right, and nothing really matters, which I'm glad I'm not wired to embody.

Well, indeed, nothing really matters.

https://mikerobertsblog.wordpress.com/2025/06/12/nothing-really-matters/

Not come across your blog before Mike. Interesting.

I keep coming back to the quote from Hamlet (if that isn't too pretentious?) " there is nothing either good or bad but thinking makes it so".

The next line is interesting though "To me, it is a prison" and it isn't entirely clear whether he is still talking about Denmark or that phrase itself.

If nothing matters/mattered, there would be nothing and nothing would ever happen.

Bim,

"If nothing matters/mattered, there would be nothing and nothing would ever happen."

I don't see the logic there. But, obviously, certain things matter to various people. However, one cannot argue the case, objectively, for whether something matters or not. One can state that, for some specified goal to be achieved, this or that matters, because it helps achieve that goal. But mattering is a human construct and so varies from human to human.

@Mile Roberts

Is the real human construct lying underneath all this confusion about whether anything (objectively) matters actually the subject-object split, and the assumption that the subject must always be a conscious/human agent (which is essentially dualism)?

Let’s ditch talking about “objectively matters” and “subjectively matters” (the latter of which seems to be the only form of mattering that you think exists, but then claim doesn’t actually matter/exist – “nothing matters”?) and just use the word “matters”. Particles, their interactions, and everything else made from them (including “subjective thoughts”), everything in the universe – all of that matters because these things exist and things actually happen because particles are of consequences to each other. It’s obvious that things will mean different things depending on perspective, but to say “nothing matters” and that consciousness is required for something to “matter” seems ludicrous to me. Saying it’s all just physics is right (or may be?), but physics is about interactions. Interaction is what makes particles matter to each other.

I guess I just don’t think the word “matters” should be restricted/forced into pertaining only to value judgements made inside (human) brains, and that definition then used to claim “nothing matters”.

Sorry to belabour the point, but I think this actually matters…

If one can say the following : “Anything that has appeared in the past light cone of any particular particle in the universe is/has been of consequence to this particle. Anything that appears in the future light cone of any particular particle in the universe will be affected in some way by this particle. The universe and everything in it (including “subjective” thoughts) is built up from such interacting particles (ultimately, ALL the inseparable, interacting particles in the universe). Therefore, everything is/was/will be of consequence to everything else.”

Then: it just seems natural to me to condense this to “everything matters”. If I can’t say this and it be a true/obvious statement, then the word “matters” seems to be very bizarrely and human-“privilegingly”defined/restricted in meaning. I think one could even make the case that such a limited definition has dualism and human supremacism built into it.

I know that in some sense this is just silly arguing over words and definitions, but I think the definition – or more importantly, the sense of the meaning – we humans have of the word “matters” is important if we are going to have the word at all. If a lousy/faulty definition leads people to claim “nothing matters” and trying to convince others of the validity of this claim based on such a definition, then I think there is a major problem with what me mean by “matters”.

Bim,

We are humans, discussing what matters. All the words we use are words that humans invented, along with their meanings. When humans claim that something matters, that last word has a meaning that humans understand.

""sadness" is a human construct"

Sadness is emotional pain. Is pain a human construct? Try jamming a red-hot poker up your nose and maintaining that pain is a human construct.

If there is "wonder to be found [in] the fact that life will go on", surely there is, by the same token, sadness at witnessing its demise (6ME)?

There's no point speculating about what some future species may or may not think. They don't exist. The species that exist *now* matter – because only now exists. That's why it *is* sad to see modernity causing such wanton destruction all over the planet.

You and other commenters can say "nothing matters" if you like, but down that road nihilism lies – and if you stare into the abyss too long, it stares back into you.

James, my first point did state that it was sad, so we agree on that 🙂

But i disagree that only *now* matters. If having some sort of life on earth is what matters to you (and Tom), then rest easy, because life will carry on for at least another billion years, and probably flourish again after humans have gone. It will be in different forms (not better or worse ones), but that would happen without us messing up the current biosphere anyway. I don't see that as nihilism. I can be both sad that we are destroying large parts of the current biosphere while being comforted by the fact that the biosphere will "recover" once we're gone and some more amazing life forms will appear.

My definition of “matters” is “is of consequence”. If something exists it matters because, by virtue of its existence, it contributes to what the universe actually is and what happens within it, regardless of what anybody thinks and how they choose to classify it (good, bad, etc.).

@Mike Roberts

Even your thought that “nothing matters” (or, if you like, the atoms and interaction underpinning it) matters in terms of what actually happens in the universe.

When two particles interact, it matters to both because it determines what happens next to both of them. All the particles mattering to each other is what gives us the universe we have and the story that actually plays out.

In terms of the whole objective vs. subjective aspect/confusion surrounding the question of “whether anything really matters at all”, something to throw into the mix is Smolin’s idea that “you can consider the universe to be the sum of all the "views" or partial perspectives of its own causal past, originating from a process of continually recreating itself through the transfer of momentum and energy” (the “Casual of Theory of Views”). The universe is essentially composed of a collection of “subjective” views.

The whole question of good and bad need not feature at all in a discussion of whether any or all things matter or not.

Lastly, if something matters to one thing in the universe, it matters to every thing else because everything is connected in some way.

Yeah, I covered that in the second last sentence of my post. That every particle in the universe affects every other particle in the universe is just physics. When someone says this or that matters, it's subjective.

Pain itself is not a human construct, and sadness is emotional pain. The meaning or mythology that we ascribe to the experience of pain or sadness can be human constructs, but at the basic level we are talking about experiences that are not unique to humans, and that represent useful genetic heritage.

One of the first lessons that I ever learned in life was when I put my hand on a hot stove to balance myself as I was learning how to walk. Ouch! I wasn't old enough to formulate human constructs, but the message was clear, 'don't touch that!'. Leaving your hand on a hot stove for any length of time could result in serious tissue damage, which then maybe result in infection and death. Thus pain is a useful evolutionary adaptation to aid individual survival.

Emotional pain, such that one might feel if they take in the reality of the 6ME, could be useful in a similar sort of 'stop doing that!' kind of way. We are, after all, destroying the substrate that we rely on, so feeling emotional pain as a warning makes sense.

All life is struggling to survive, and we are a part of that struggle. Pain and emotions are not unique to humans, so having empathy for non humans also makes sense. We do have some useful genetic tools including pain and emotions that could be useful to life in its current struggle, but in modernity, these have been largely misunderstood, hijacked, or misfired.

"Pain and emotions are not unique to humans" – I could not agree more.

It's human-centric to call sadness a "human construct". Eg a rabbit with electrodes protruding from his head, strapped to a laboratory bench, surrounded by white-coated, cold-hearted nerds, could reasonably be described as being sad. Conversely, another rabbit, playing in a meadow on a sunny day, could be said to be happy.

It's not 'anthropomorphising' – they are animals, just as humans are, happy and sad, just as humans are.

People's emotions have indeed been hijacked by modernity. It seems to have happened slowly, as a constrictor chokes its prey. The system itself is now a true AI, operating outside the control of any one person or group while giving them the illusion of being in charge (very much like in 'The Matrix' in fact). Irrespective of how humans try to stop it, when its fuel (FF etc) runs out it will die, but life will not.

There are studies of fruit flies where they change their levels of aggression in response to repeated failures and seem to experience something like frustration. https://phys.org/news/2024-01-sexual-failures-social-stress-fruit.html

Does a spider that is running away from you feel fear? (I leave them alone in any case). Is it just instinct? It's impossible to comprehend the subjective experience of other organisms, but the building blocks of emotions seem to permeate through even so-called simpler life forms.

Yes, I read of a similar experiment in which fruit flies deprived of sex drank more alcohol (just like humans!)

Really though, what gives us the *right* to experiment on animals at all? If, like Descartes, one views them as mere mechanisms, then maybe it becomes easier. Mechanisms cannot feel.

Here, we come to the crunch. Good and bad, right and wrong etc. Those who believe physics to be the beginning and end have no grounds to appeal to what is 'right', or to what humans 'ought' to do. They ought do follow path x because… it benefits their survival as a species in the long run? Is that *it*? Or are 'good' and 'bad' real, with all that that implies?

To me, animal experiments are wrong. Cruelty is wrong. The ends *do not* always justify the means – in fact they rarely do so, where humans are involved (see also: most wars).

Science 'works' and we use it – so? It is but one means of apprehending (and controlling – look how that went) reality.

What I continually fail to understand is the need people have that physics (or science) be the ultimate foundation of reality. Isn't it better to simply say "I *don't know* the ultimate foundation of reality"? Then all options remain open.

Why the need for certainty?

The perspective that good vs evil is what is of ultimate importance, as if everything else is background while this classic dichotomy plays out as drama on the cosmic stage, I do find to be humanocentric. There are parallels with the Star Wars universe, Tolkien's Lord of the Rings, or even central Biblical themes, such as Adam and Eve eating from the tree of the 'knowledge of good and evil'. – We don't live in any of these worlds, nor should we pretend to.

It's my intuition that we're better off at a small scale where our human imperfections and moral failings can express themselves freely without causing serious harm. We've created something of a self-fulfilling prophecy in elevating our powers with extremely destructive technologies like nuclear weapons, where moral failings can now cause catastrophic consequences.

Throughout my life I 've taught multiple cats to play-wrestle with my hand, for fun. Some really got into it, they would grab my wrist and chew on my fingers and kick my arm with their hind legs, they'd even puff up their backs, circle my hand menacingly and pounce. It was all good fun, but one thing to note is that each cat that I did this with instinctively knew that it was 'play'. They would bite playfully, not with the intention of breaking the skin (none of them were declawed so often I would bleed a little anyway). The point I'm getting at is there is some empathetic connection here, between human and cat, and of course it has been shown that a cat's brain releases oxytocin when a friendly human looks into its eyes, it feels something like love.

In the right context, emotions like love and empathy, a sense of belonging, properly expressed, would likely tame most antisocial behaviors in humans. Reinforced by mating selection preferences for generosity, honestly, etc. Good vibes would mostly persist in a tribe, I would venture, without any grand narrative needed on the nature of good and evil, or attendant legal structures. Empathy is sufficient to bind cruelty. When we have to read tomes on the nature of good and evil (especially when gods get involved) is when we have a problem.

But I never said "good vs evil is what is of ultimate importance".

I said "Those who believe physics to be the beginning and end have no grounds to appeal to what is 'right', or to what humans 'ought' to do".

Of course, small-scale societies or tribes are better. They are usually not hierarchical at all. The bigger the hierarchy, the more destruction follows (corporations/governments, nation states being the most egregious examples {so far}).

The 'tree of knowledge' story can be interpreted many ways. Maybe the advent of agriculture *was* a descent from the 'Garden of Eden' (small, egalitarian tribes of hunter-gatherers). Similarly, scientific knowledge has given humans great control over the physical world – far too much, as it turned out. Science marched (marches) foward without right or wrong being considered, only 'utility'.

There's no need to read tomes on the nature of good and evil (or on anything, really). People instinctively do know the difference between right and wrong.

James said: "A paradigm shift is needed, such that people understand how their humdrum lives kill the living world."

Yes, a paradigm shift is needed. But it has been present since about 1966 in the counterculture. Just ask one of the old, snaggle-toothed hippies from the 1960s in your neighborhood. They may not be as articulate as you like, but they picked up on something that was happening at the time. Then they did something about it. As I say so often, "If YOU would have listened to US fifty-five years ago, WE wouldn't be in trouble NOW."

Let's get granular. In order to have a paradigm shift at scale, you will need to have an accumulation of individuals shifting their paradigms. We saw this in the 1960-70s. But the mainstream did not acknowledge or accept this paradigm shift. Instead, they disrespected our efforts, jailed us, and killed a lot of us. Now you have only a few left. If you want a paradigm shift this time around YOU are going to have to do it for yourself on an individual basis. Then you will have to encourage others to do the same. At some point in the near future, there will be a collapse and dieoff. Those of you who have undergone a paradigm shift will have a greater probability of survival and can then help others. Then you can build local, sustainable communities. But you will have to learn how to use the power that is lying about all around you. While you are waiting for collapse, there are many advantages to shifting your paradigm right now and in the mid-term future. Growing your own food is just one example.

The next level is figuring out how to make your own paradigm shift. I provide templates and examples in my 2024 book, Paradigms for Adaptation. The thesis here is that only YOU know your own unique situation, so you have to build your own new paradigms. The off-the-shelf, one-size-fits-all paradigms are usually designed to make money and continue the presenty System. If you want REAL change you have to do it yourself. This is not as difficult as it sounds.

There are plenty of people saying, "It's bad." There are plenty of people saying, "Someone has to DO something." There are plenty of people saying, "Buy my product and life will be grand." There are plenty of people whining and winging and wringing their hands. There are only a few actually willing to get their hands dirty doing positive things. You can be one of the latter.

Whatever those old hippies 'did about it', it didn't work, did it? A paradigm shift means the whole culture must shift, not just a few weed-smoking deadbeats. One does not have to be a hippy to see that the prevailing culture is sick af.

It's all very well saying "grow your own food" and "build local communities" – not that easy with no land or money.

But, with or without a PS, the current system is (I'm glad to say) doomed anyway.

So I'll just keep on "winging" and wringing my hands until the house of cards comes down.

No, no and hell no! A paradigm shift is individualistic. It does not need total acceptance by everyone in order to provide guidance and real material success. Let's use the "grow your own food" paradigm as an example. When I grew up on a dairy farm in the 1950-60s, we were dirt poor, but we had plenty to eat. This kept us alive. You can keep putting patches on your clothes for a long time when you have milk and meat from your own labor, land and cows. When I was a market gardener I made about 50 cents/hour for all the blood and sweat I put into the land. But we had plenty to eat AND when we sold out and moved to France, we got a better price for our farm than if I had done nothing to improve the soil. In addition, we got the usual return on sweat equity a farmer gets when they sell out.

There are plenty of ways to grow your own food. As I mentioned, YOU have to come up with your own plan and actually do the work. You might want to consider how to get an edge when collapse hits. In the meantime, shifting your paradigms will provide you with benefits in the short-term, mid-term and long-term.

There is one area in which biodiversity seems to be increasing, an area that may, in time, facilitate the reduction of the human population: drug resistant bacteria. It is a logical outcome in ecosystems: the larger a population becomes, the more useful it becomes as a resource for those who feed on it.

Humans ( As many as possible) should engage with the byproducts of modernity (late stage capitalism, industrial excess, Overshoot) in order to actively accelerate its hospice phase. Step back, disengage, and let the system collapse faster, so the larger population can wake up to the path ahead!!

Well, Tom; glad to see you are accepting dieoff (or die-off if you prefer). The fact that a species in overshoot will experience a dramatic decrease in population has been known for over a hundred years. The fact that this can also happen to humans if we overshoot our population resources has been around for over fifty years. I myself made a vow not to have children in 1970 because of this fact, back when the global population was less than half what it is now. [One can always help raise other people's children. That is what I did,] It is not just the absolute number of humans on the planet. Some humans consume far more resources than others. The Indian Ambassador to the UN made a speech in 1965 nothing that pushing birth control on India was misplaced because an American child would use 19 times more resources in his/her life than an Indian child. The same contradiction applies to day. It is NOT that there are too many humans per se. It is that there are waaaaaaayyyyy too many Americans. This was blatantly obvious by the first Earth Day in 1970.

When we moved to France in 2018, we entered a country where the per capita energy use was only about half of what is was for the US. If we had moved to Spain or Portugal, it would have been about one-fourth. Yet these are all modern countries with better health care and public transport and cheaper costs of living. The problem is not overpopulation around the world. It is the greedy, warmongering, overpopulated US of A.

Dieoff is in our future. I have been saying this for over fifty years. And there is nothing special about me. I am just willing to accept scientific facts. But some people will survive. The human race has suffered several bottlenecks in the last million years and the total global population was reduced to 5000-10,000 individuals. I suspect that this time around, the global population will drop to 1-1.5 billion by 2100.

You hit a good point about population. If 8 billion lived like those in India, we wouldn't have an Earth Day because we'd use less than a planet's primary productivity each year. Overshoot is about living unsustainably, not about pure numbers.

Earth Day is, though, only about ecological resources, not mineral resources. If our civilisation lived like Indians but still used non-renewable resources, it would still be unsustainable, even if not technically in overshoot.

Approximately 0% of people concern themselves with population ethics. Our collective behaviour is arguably far beyond immoral, selfish, delusional, and ignorant – it is evil. But ask anyone to Do The Math on that, and the conversation instantly falters fatally.

I blogged about overshoot a bit, but have given up.

The first Earth Day in 1970 was focused on the total resource problem, which included overuse and abuse of mineral resources I was there and worked locally in Minneapolis, leafleting and selling books and buttons. There was somewhat of a schism, with the hardcore antiwar protesters seeing the environmentalists draining human resources from the antiwar movement. Nixon certainly thought this to be the case. But that was not true in even theory or method, as The Movement continued until the War ended in 1975. That is when the fracturing occurred. You can look at the general student strike over the Cambodian Invasion and Kent State for corroboration.

If you are big on Systems Theory, you can see The Movement as a coordinated response to a System breakdown. But I am not one of the adherents of Systems Theory, especially given the history of the Rand Corporation and how Systems Theory was key to the debacle in Vietnam. And it was not just mis-application by McNamara and others. It is flawed in concept. Other social and natural scientists disagree.

None of this is new, TM keeps pulling it together though.

Pentti Linkola talks of much of this in "Will Life Prevail". Be careful, you'll be labeled an eco-fascist 🙂 His natural inclination is to preserve the ecology, so humans have to go, by force. His argument is the worst invention ever by humanity is the road, maybe he's right and it's not Agriculture.

Graeber (an actual anthropologist) is another and mentions some of this in Debt: The First 5000 years

and in this article (albeit I have not read the authors book)

https://aeon.co/essays/why-inequality-bothers-people-more-than-poverty

>But research conducted among the Ju/’hoansi in the 1950s and ’60s when they could still hunt and gather freely turned established views of social evolution on their head. Up until then, it was widely believed that hunter-gatherers endured a near-constant battle against starvation, and that it was only with the advent of agriculture that we began to free ourselves from the capricious tyranny of nature. When in 1964 a young Canadian anthropologist, Richard Borshay Lee, conducted a series of simple economic input/output analyses of the Ju/’hoansi as they went about their daily lives, he revealed that not only did they make a good living from hunting and gathering, but that they were also well-nourished and content. Most remarkably, his research revealed that the Ju/’hoansi managed this on the basis of little more than 15 hours’ work per week. On the strength of this finding, the anthropologist Marshall Sahlins in Stone Age Economics (1972) renamed hunter-gatherers ‘the original affluent society’.

Then we have the maligned philosopher John Gray for pointing out

>“The destruction of the natural world is not the result of global capitalism, industrialisation, ‘Western civilisation’ or any flaw in human institutions. It is a consequence of the evolutionary success of an exceptionally rapacious primate. Throughout all of history and prehistory, human advance has coincided with ecological devastation.” ― John Gray, Straw Dogs: Thoughts On Humans And Other Animals

An interesting anecdote, I read an article in Project Syndicate (I think it was?), from an environmentalist who said "no serious environmentalist thinks over population is an issue" 🙂 so this nonsense is near ubiquitous.

My own opinion ? Climate change is "the solution", not the problem,. we are so terraforming the biosphere our current civilisation will no longer exist and I don't think any reading of Ishmael (I disliked it but read it some time ago) by any number of people will help, as it did not with Limits to Growth

Murderer! Just kidding 😀 Having experienced the same reactions when broaching this topic also for things I never said, here’s my take on how it plays out: it’s of course hilarious to be called an ecofascist when you’re advocating for a return to small-band egalitarianism (the opposite of fascism). But the fear/denial of their own death, fantasies of progress, and the addiction to comfort and convenience all being called out in one fell swoop – which is typically how any mention of population is interpreted by those in affluent societies – leads to the aforementioned rageful sputtering/defensiveness/comparisons to genocidal dictators. Now that the nerve is struck, the attempt to regain the moral high ground in their own eyes follows, by taking the (already loud and overbearing) side of the currently living humans vs the unfortunately voiceless other beings or future humans. Finally, smug and satisfied, and safe on the majority side, they can now justify doing absolutely nothing to change their behavior or confront their delusions.

So I agree that framing any suggestions as for *future* humans is necessary in order to avoid the taking-it-personally, though it’s odd to me, as I would trade it all for hunter-gatherer life in a heartbeat if that was actually on the table! I have no idea how to deal with those who can’t even stomach the mention of death, or the notion that 8 billion humans simply cannot all live to be 90 in air-conditioned comfort staring at smartphones all day, or that pursuing such minor-league pleasures 24/7 is not the goal of living and the path to eternal happiness, which is a legit part of the problem, so kudos to any efforts to clarify what freedom actually means, and where it lies. It isn’t in constantly being jabbed with the dopamine stick.

Which leads me to the “likes” and luxuries – are they really SO wonderful? Besides all being behind a paywall, so we get to degrade ourselves in myriad ways to access the necessary funds, we’ve established that our likes have terrible consequences outside of ourselves, but what about on us? Are they actually “good” for us? Are they enabling civilization more than anything? How do you develop resilience or tolerance for temperature changes living in a perpetually 72 degree cocoon, and ultimately, what kind of person does it make? Is it possible they, while initially seeming great, backfire? I can give loads of other examples. Squishy mattresses and furniture? Warp your spine and lead to painful, expensive surgeries. Phones? My Gen Z acquaintances lament how much more fun life must have been before phones (and I concur). Amazon (not the forest)? Yay, it’s way easier to buy more junk, just what we needed! Toilets? Not made for squatting. Goodbye fresh water, hello hemorrhoids. Point being, there’s even more downsides to everything.

If it was actually working and people were having a blast living and brimming with joy, I *might* feel slightly better about all the destruction, but that is not the reality I see, no matter what social media implies about the nonstop fun of this zany human zoo. To me, looking at the fascinating and magical beings results of evolutionary deep time that are disappearing to make way for more of it, there’s just no comparison, which makes it all the more tragic.

This might be controversial, but challenges to our sentimental myths around nuclear families and having children, I hope, will accelerate the declines we are already seeing. If families were considered tribes, we’d literally have hundreds of millions of them. I’ve always found it odd that those who opted out of breeding were considered selfish when I hear some of the reasons people do have children, like as a retirement plan, to “fix” themselves, or because they liked playing with dolls. There’s plenty of existing people who need love and support! Rita Rudner had it right: “we longed for the pitter-patter of little feet, so we got a dog. It’s cheaper, and you get more feet”

You're a wise one, Liza. I always enjoy and learn from your points.

Christopher Ryan does a good job in Civilized to Death knocking the "Likes" as not all that.

As for the "selfish" charge, I agree: many reasons people do have kids is selfish. Perhaps most decisions we make in our culture are selfish (how we're trained: nobody more important than ourselves), but depending on needs the outcomes can be different. I get it, though. Being a parent can suck, and parents frequently sacrifice their own needs for those of their kids, which sure seems selfless to them. But back to the reason for having kids in the first place…

I’m really happy to hear the points are useful, and always appreciate having the breathing room provided here to air unconventional thoughts. This blog has helped me in far-reaching and unexpected ways.

It’s a hard-won wisdom. I imagine you, and many others here, could say the same (though good to know there are other ways to end up here questioning modernity that aren’t *quite* as grim and sordid as my particular journey was!)

I really need to reread Civilized to Death. Totally agree that a distinction needs to be made between the job of parenting, and the choice to have children especially amongst the richest and most consumerist. Still working on that framing, though…

I had one more point on the original post, around the “why do you hate people so much? I’m being serious!” That’s a great question. I sense an undercurrent of misanthropy amongst population defenders, like they secretly (or not so secretly, in the case of evangelicals) wish for human extinction and Earth’s destruction, like they’d rather us all die that have to live with limits or rationing, or they subscribe to Rapture fantasy (note the recent failed predictions), like a child not getting the toy they want and deciding to burn down the whole house. I wonder if it’s partly an unconscious stress response to the exact situation of human overcrowding they vehemently defend. Adding the same amount of people (2 billion) in the last 25 years as existed in the first 9,950 years of civilization is a mind-boggling amount of humans and it affects everything about our lives, but as it’s so rarely talked about, no one actively factors it in, leaving it to seep out in disturbing ways.

A pertinent piece that mentions the efforts of pronatalists to increase birth rates through legislative changes:

https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2025/sep/28/should-we-have-children-burning-planet-author-bri-lee-seed-book-antinatalism-seriously-taboo

The “Modernity Machine” always seems to come up with ways to lubricate the cogs…

Is it "you first," or is it, really, "me last."

Although pretty far off-topic, a couple clarifications to James' characterization of the physics view.

1) "Isn't it better to simply say 'I don't know'? … Why the need for certainty?" I suspect it would be hard to find an assertion from me that physics is certainly the whole story, explicitly ruling out any other view. I might often shortcut all the cumbersome caveats and represent a strong sense that physics is all we need as a foundation. My basic stance is: limited imagination is no reason to conclude that physics (as we know it) can't be the entire basis. No evidence otherwise, just substantial, unsurprising gaps in understanding (that's on us). But it seems entirely capable of being good enough, without needing to pine for something else simply to fill a void in our comprehension. Until it becomes impossible to accomplish all that we observe with physics (given limited brains), it's really going out on a limb to conjure anything else. Stick with what we know for sure… Don't project our own glaring gaps onto the metaphysical foundation.

2) "Those who believe physics to be the beginning and end…" While not germane to the point about good vs. bad, this phrasing might indicate a disconnect. I'm comfortable with physics as the beginning; the foundation. But then the view from there becomes one of expansivism in terms of all the open-ended tricks physics can get up to, including Life and the sensation of consciousness. "End" seems so closed and final. Physics can be a perfectly adequate beginning, allowing everything amazing phenomenon we encounter to blossom from there, without known exception. It's not a weak position, while claiming there must be more is not really defensible. Might there be more? Sure, but why do we need there to be?

Maybe OT, but it seems as though all that life being destroyed by a human-caused 6ME represents some kind of sin… Not a logical statement, admittedly, and perhaps a weak position. Saying it's ok 'because new species will appear' somehow misses the gravity of the situation.

"[There] is no reason to conclude that physics (as we know it) can't be the entire basis" True, but that doesn't mean it is *certainly* the entire basis. Lack of evidence that science can't account for everything doesn't mean that it definitely *can* do so.

I only say science isn't the sole route to truth. Reason, intuition… some things can be known, yet unprovable (even mathematical truths).

Surely there is physics we don't know about. But there might be things we *cannot* know about – "unknown unknowns" – that may or may not be physical.

What do we really "know for sure"? All we directly know is our own experience (via consciousness, about which there is still no consensus).

Claiming there *must* be more than what is described by science is not defensible, I agree. Certainty is to be avoided, certainly.

Is life merely mechanical? Or is it a dome of many-coloured glass that stains the white radiance of eternity?

I am not sure if the difficulty lies in how physics can feel limiting like an "is that all?" situation for many.But for me, it has the opposite/magical effect. It fills me with wonder on how meaning can derive from simple patterns,particles,activities,and behaviours.It doesnt close the door for me.It opens it much wider.

What difficulty? Physics describes nature at all observable scales. Its conclusions are testable by experiments, and it has enabled countless scientific breakthroughs and advanced technology. Yes, it *is* wonderful how structure can appear by the interactions of particles and forces…

But.

It's ultimately based on mathematics. Gödel showed that there will always be mathematical statements that are true but unprovable. Thus limitations apply to *any* formal set of rules – including physics. So there will always be things that are true but not described by physics.

That last leap is a doozy: does not follow. First, physics *utilizes* math, but is not *based* on (derivable from) math. An electron is not a figment of math, but a real nugget that has properties of interaction. You can't prove the existence of an electron by any formal theorem, but that doesn't make it vanish in a puff of logic. Physics is not a formal set of rules but a physical manifestation of real stuff that interact (apparently according to rules that require no separate proof—just descriptive capacity). Gödel's theorem says nothing about empirical reality or whether everything can be described by physics: just that the abstract logical systems employed as tools in the description might not themselves all be provable. Physics doesn't care. Physics can't, for instance, prove hardly anything at all (and not it's goal), like whether there should be something rather than nothing. It's descriptive, not axiomatic. Wrong tree.

Physics has proved loads of things, eg mass and energy being equivalent, there being a minimum temperature, the Earth being a sphere etc etc. but has nothing to say about why there's something rather than nothing, as that is beyond it – even though it's obviously true.

Gödel's theorem was about maths, and maths is the language of physics. That seems to imply that any description of reality (which is what physics is) will never contain *all* of reality. Saying 'physics doesn't care' has no relevance to what it can or can't describe.