Fossil fuels have leveraged human power and ingenuity to a remarkable degree. Their discovery and accelerating utilization utterly transformed lifestyles, achievements, and even how we perceive ourselves as a species.

Yet, one thing we know for certain about fossil fuels is that they are a finite resource on this planet—slowly developed in select locations over hundreds of millions of years and being used about a million times faster than the rate of production. We know that we have already consumed a sizable fraction of the initial inheritance: perhaps now halfway through the irreplaceable allotment of oil. So we know that this phase of the human adventure is a temporary one.

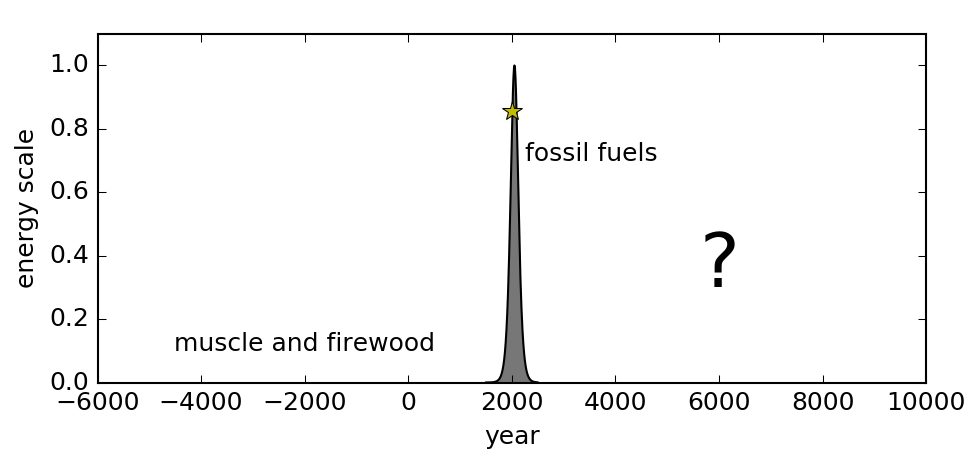

The quintessential graphic for conveying this idea is one I have used many times, because I believe it is the most important plot modern humans could possibly absorb. Human energy use has shot up in the last 150 years, and in the context of fossil fuels will plummet on a similar timescale, leaving—what, exactly?

The fossil fuel energy explosion that powers our current fireworks show is a momentary phenomenon that will be over in a historically short time.

Over timescales relevant to civilization (which began 10,000 years ago with agriculture and cities), plots of almost anything relating to human activity look like hockey sticks: population, agricultural output, industrial output, mined materials, deforestation, species extinctions, and so on [see this later post]. Many of these certainly correlate to population growth, but the per capita impacts also have shot up, compounding the human footprint to a frightening degree. At this point, humans and their livestock account for 96% of mammal mass on the planet, leaving a mere 4% for all wild animals (half of this from massive whales and other marine mammals). It’s not just a footprint any more: it’s a boot on the throat of the planet, leaving non-human life gasping and silently begging for even a little mercy. Is anybody getting video of this?

Almost all of this explosive impact can be traced to fossil fuels, which I have started visualizing as a suit donned by humans that has given us literal superpowers. What would we be without our fancy suit?

It’s All Based on Fossil Fuels

The fossil fuel suit epiphany was partly stimulated by recognizing that we have not built a single hydroelectric dam of any consequence without the aid of fossil fuels. No nuclear plants, wind turbines, or solar panels have been made without the bulk of the work (energy) required coming from fossil fuels. From mining to earth-moving to materials processing to transporting ingredients and final products, the renewable/alternative energy enterprise has been a fossil endeavor through and through.

So when you look at plots of global energy trends, seeing fossil fuels towering over the diminutive-but-rising renewables, recognize that even those alternatives are just a ghostly reflection of fossil fuel use.

That in itself is not particularly problematic. Based on the favorable energy return on energy invested (EROEI) in renewable technologies—well above break-even—it is possible and beneficial to leverage fossil fuel use into non-fossil forms. This non-fossil augmentation could be treated as a form of efficiency. Rather than getting 100% of our energy from fossil fuels, we get only 80% in direct form and squeeze another 20% out of other fossil-enabled resources.

The bigger problem is that the processing of industrial materials (cement, steel, aluminum, etc.) requires a great deal of heat, which currently is obtained by burning fossil fuels. Almost all alternatives to fossil fuels (the exception being burning biomass) create electricity, which is not particularly suited to creating the kind of heat required in industry.

To understand this, think about the usual method of creating electrical heat. Toasters, space heaters, dryers, and stove tops use metal coils that get hot and even glow orange. But to get hot enough to melt steel, you’d also melt the coils. So that’s no way to go. Electric arcs can make small volumes very hot (think arc-welding), but only tungsten electrodes resist melting under the arc’s heat. Put simply, creating enough heat—in large volumes—to “destroy” (melt, re-form) materials will tend to destroy the heating agent as well. In the case of fossil fuels, we don’t care if the heating agent (fuel) is “destroyed” (burned) in the process of creating heat: that’s what we do with them in any application. But we don’t want to destroy electrical heaters in the process of creating enough heat for an industrial application.

This view may be oversimplified, but I think it helps us understand the nature of the challenge, and why heating by burning is an entirely different animal—and much easier—than heating by electricity.

Without Fossil Fuels?

What, then, is left when fossil fuels are more scarce? One possibility is a well ordered world in which sophisticated new technology maintains our modern capabilities in an utterly transformed way. This is probably the default assumption of most, but not a carefully examined one that can be easily supported based on current knowledge/evidence: owing in part to the grossly distorted perspective fostered by the fossil fuel age. The other world is one in which life gets tougher, high technology is harder to maintain, resource wars are the most obvious and common strategies to secure basic needs, and the resulting disruptions make it difficult to achieve the utopian vision of a high-tech future dependent on global supplies. Today’s energy-rich lifestyle may well turn out to be a privilege conferred by the fossil fuel suit, as if satisfying a dress code for the high-tech club. Once the enabling elixir is spent, we may be kicked out of the club.

While we can’t know the future, one thing we can do is ask what might be learned from the past. We once lived in a world without fossil fuel use. The year 1712 marks a turning point, when the first commercial steam engine—powered by coal—was used to pump water from coal mines in order to access more coal. Did you notice a theme there? What inventions existed before the start of the fossil fuel era? Those can be truly said to be independent of fossil fuels. After this date, the capabilities afforded by an abundant energy source slowly permeated the world and opened new possibilities. How many of the subsequent inventions can trace some dependency to fossil fuels somewhere in their lineage? Hint: the flurry of inventions—as listed here—tended to come out of places that were early-adopters of fossil energy (i.e., England, Scotland, France).

It is entertaining to muse about what we might not have today if fossil fuels had never been available or utilized. Would we have computers or lasers? Would we have skyscrapers or photovoltaics? Would we have understood nuclear energy or fundamental physics that relied on high-energy experiments? Would we even have bicycles? It is, of course, impossible to say with any certainty. But since all of these things first emerged after fossil fuels took hold, and built upon each other in ways that at least had access to the benefits of fossil fuels, it is plausible that most of what we see around us in the developed world owes its existence to fossil fuels. In fact, one might say that it is a much tougher case to argue the counterfactual that we would still have comparable technology today had fossil fuels not burst onto the scene.

Aren’t We Special?

People tend to prefer the narrative that we, ourselves, are the superheros, and that our superpowers are not from the fossil fuel suit, but are cognitive in nature. Yet we have the same neural hardware (if not slightly downsized) as our prehistoric ancestors. The main cognitive revolution happened about 70,000 years ago when humans started to believe in things that do not exist (like spirits or potential future gains) that allowed large-scale coordination and shared identity to outcompete evolution’s more biophysical tricks of sharp teeth/claws, speed, strength, camouflage, poison, or overwhelming numbers. Global spread of homo sapiens and megafauna extinctions quickly followed, and it is at this point that the human experiment began to smolder: something was off. About 10,000 years ago, agriculture started and the fist visible flame ignited. About 300–400 years ago, the Enlightenment lit a fuse by developing a scientific approach to understanding the world. It was not long before the fuse found fossil fuels and we now witness the predictable explosion that ensued. The explosion is breathtakingly rapid on any meaningful timeline, only appearing in slow motion to the few generations experiencing the phenomenon and thus seeming “normal.”

So we can trace some part of our current planetary dominance to human ingenuity, but perhaps the lion’s share actually is attributable to the energy bonanza—as suggested by the dramatic change in the pace of innovation before and after the fossil transition.

For most people, however, the critical role fossil fuels played is easily overlooked. In so doing, we form a grotesquely warped view of who we are. Anything seems possible: we would appear to have transcended nature to be the masters of the planet. Lots of self-assigned rights and privileges follow. It is an age of human exceptionalism. The resulting narrative is highly appealing and stubbornly held even when cracks in the foundation are evident. Many fewer life-changing inventions have entered the scene in the last 60 years than in the 60 years prior to that. Such an inconvenient and obvious truth threatens deeply held beliefs and is quickly brushed aside as anything but obvious.

That leaves the question: if most of what we praise about ourselves is not so much us but our fossil fuel suit (we do look good in it, don’t we?), then what’s left when our empire loses its cladding? Just how feeble, pathetic, and dull are we, under that thick and powerful shroud?

I am not claiming to have a definitive answer, although it is clear where my suspicions lie. The fairest thing to say is that we do not really know. We don’t know what will be possible in a world beyond fossil fuels. I would rest easier if more people acknowledged this constructive uncertainty. Decisions about the future will simply be better if admitting limitations to resources and to our own capabilities, while pulling back from some intoxicated vision of human triumph over nature.

Views: 11251

Good questions all.

A couple thoughts…

I like to use a rock in a pond relationship to think about fossil fuels and renewables (or pretty much everything else). Fossil fuels are the rock thrown into the pond. Renewables (and almost everything else) are one of the ripples.

Another question that worries me is whether democracy, or civilization itself, are purely artifacts of energy surplus. I suspect they are. This is worrying because it suggests that a reduction in available surplus energy will likely result in a reduction in the availability of democratic values and civilized behaviors/living arrangements. Can we get from here (high energy surplus) to there (low energy surplus) and hold on to the best aspects of civilized human endeavor? I don't know. I hope so. But I don't know.

Hi Brian,

Yes, I agree. I strongly suspect that democracy requires an expanding pie of resources. Is it really a coincidence that the first and only large republic since ancient times germinated on the cusp of a vast virgin continent that was rich with resources? Or that democratic values only (yet suddenly) started to prevail in the rest of the world after the discovery of petroleum—which unlocked abundant new resources? I think not.

In an age of expanding resources, voters make good supervisors of government: the incentive is to keep government in its place to allow the people to enjoy the fruits of their own prosperity.

In an age of privation and declining resources, however, the overwhelming incentive is for the poor and unemployed masses to use the ballot box to vote themselves money and resources, cannibalizing the society's infrastructure in the process. No elected official could tell the people: "We have to permanently reduce your gasoline ration so that we can pay for the hydroelectric system." The result is a hopelessly dysfunctional government, eventually leading to popular demand for a dictator to come in and sort the mess out.

Very good essay. I'll answer your concluding question about what we'll be after we've burned all the fossil energy:

An intelligent rapacious social fire ape that believes in gods and denies death.

It seems to me the most important variable in this equation we call modern civilization is population. Population growth is both driven by fossil fuels and fossil fuel usage is also driven by population growth. This circular dynamic feedback loop falls apart as fossil fuels diminish in availability leading to an inevitable decline in both population and fossil fuel usage. I seem to recall that the natural carrying capacity of the earth is somewhere south of 1 billion people. If the population is reduced to levels like this then alternative forms of energy become more adequate for sustaining that level of population. Natural production of food also become more plausible like it was before the fossil fuel revolution. So if this is true then the real issue isn't the limitations of fossil fuel availability to sustain us but the need to limit or reduce our numbers. Most of these reductions will likely happen naturally due to environmental declines due to climate change and the food scarcities that will result regardless of what happens to how we use or not continue to use fossil fuels. The transition will be horrific but unfortunately necessary because we simply won't do the things necessary for a soft landing. In other words, things will work themselves out one way or another. If we ignore the 800 lb gorilla that is population growth we overlook the true main driver of this whole dilemma. The earth was never meant to support this many people sustainably and it simply won't in the long run.

The Chinese have never had an intoxicated vision of human triumph over nature. On the contrary. They have nature preserves that are 3,000 years old, and a variety and density of flora and fauna unmatched elsewhere. Tigers, for example prey on sheep outside Beijing which itself is home to 512 kinds of birdlife.

China also commissions more renewable energy each year than the rest of the world combined.

I got the opposite impression from recent student interactions. When confronted with limits, Chinese students tended to react with a staggering degree of human-over-nature dominance. For instance, when presented with seasonal lulls in hydroelectric plants: why don't we make it rain more? Wind capacity factors limit output: can we generate wind to keep a steady flow? Solar panels are dead at night: rig lights to shine at night time. Granted, these also flirt with perpetual motion nonsense, but I was often stunned by the fairly prevalent attitude among Chinese students that we can master any problem and shape the world to our purposes.

' The Retreat of the Elephants : An Environmental History of China "

by Mark Elvin is 500+ pages of evidence to the contrary.

The devastation of the natural world by agricultural and industrial

civilisation in China has been enormous. Read some of the reviews of it on Amazon.

Hi Godfree,

I was discussing this very topic with a Chinese friend of mine yesterday. She said that the ancient Chinese belief was definitely that humans must always be in balance with nature, and that if you become arrogant with nature then you will be destroying yourself. Very different from the Western idea of man against nature.

However, the communists made it their business to stamp out most of traditional Chinese culture in the name of heavy industry and economic progress, she said. The wholesale destruction of natural resources is ongoing.

She says wild preserves exist in some remote places where development is not economically viable, and there are projects to preserve some animals like the panda bear. But otherwise, she says there is no such thing as environmentalism or Thoreau-style naturalism in the modern Chinese mind, and it's full steam ahead in terms of resource extraction.

Is that humour ?

There isn't a single tiger left in China, a lot due to a Mao directive to exterminate them as "pest".

In fact Mao also had a directive to exterminate sparrows, which lead to a famine with the proliferation of insects.

Not even talking about the result of "traditional chinese medicine" or food delicacies with Rhino horns, shark fins, etc …

Excellent article, as always!

I have been thinking hard about what a plan for the future might mean. We can't plan for unknowable events, but we can preserve some of the knowledge people might need to make materials, chemicals, and manufactured goods in a lower-energy environment.

John Michael Greer points out some of the reasons why so many technologies were lost in the collapse of Rome's economy:

(1). No demand for new production. A steep drop in demand (and population) left an abundant stock of materials on hand, removing the market for new production for several generations.

(2). Centralization. Production of key components (like Roman roofing tiles) was highly centralized in a few large factories, resulting in communities having no need for local manufacture, and thus no knowledge of it.

(3). Specialization accentuated the process of knowledge loss. Even in places where the factories existed, they were geared toward production of specialized types of pottery, not small-scale manufacture of the whole range needed by communities. Worse, the knowledge possessed by a factory operator seemed useless without the specialized inputs for that factory, and was thus quickly forgotten.

So, we just need to be sure to digitize and preserve all our books, right? I'm not so sure. While in high school, when not working in my mentor's laboratory I spent much of my summers browsing the enormous collection of books in the University of Massachusetts' library.

What I learned:

(1). The academy does not bother itself with recording much trade knowledge. For example, go into your university library and try to answer the question: "How do you grind glass to make a microscope lens?" What are the basic principles? How might one get started?

(2). If you do set about trying to answer such a question (as I did), I found that reading 19th-century books on the topic is often the best way forward, as more modern books assume knowledge of the basics, or assume the mechanization of the process. But even there, it's easy to lose the thread.

(3). The internal procedural manuals of industry, or perhaps what is unwritten but which a seasoned lens-grinder could write down in a few pages of type-written notes, are crucial.

We need a project to preserve basic manufacturing knowledge. Otherwise, as factories shut down, highly-skilled craftsmen will take their knowledge into retirement with them. (As we're discovering in trying to re-shore manufacturing that we off-shored in the 1980's!)

As energy becomes scarcer, it is possible that the process of specialization might have one last hurrah, in search of more efficiency. (E.g., More use of robotics and computer-automated processes). It is vital that we preserve knowledge of the older, less efficient, less specialized processes.

How do you build a telephone switching station that does not rely on computer chips? Pretty soon, we might want to know.

Somehow the phrase "turtles all the way down" comes to mind – pick almost any modern manufactured item and think about all the interdependencies of highly specialized production steps: resource extraction, shipping, refinement, processing, assembly, distribution – all dependent on machinery and worksites which in turn depend on other factories and worksites and on and on. As cheap energy and a stable environment fades, the disruption will be unimaginable.

Given we're abandoning copper now, I'm not sure if it will make sense to reconstruct telephone landlines in the future. I suspect our descendants will be dealing with more immediate challenges like all the contamination from low-lying landfills that will be inundated by rising seas – all those gigatons of buried plastic. Maybe we'll start mining them for low grade ores.

Hi Marcus,

Good point! Especially about the copper: we're down to mining 0.2% ore grades, which require moving tons of earth with diesel just to get a few pounds of copper. I should have set my sights on something lower. Maybe how to locally make small quantities of anesthetic ether for surgery like they did in the 1840's.

And if we end up banging rocks together, then the story that we humans once walked on the moon should be told, if only for the sake of the story.

The amount of useful knowledge in the world does not depend on the number of appropriate books in a library but on the number of people who can read them, understand them and apply that understanding.

Imagine that all the knowledge of humankind was preserved in a gigantic building full of books and reading glasses. If no one ever goes in, the knowledge doesn't really exist in any meaningful, or at least useful, sense. And even if people go in and start reading about basic technologies, how long would it take them to acquire the ability to comprehend, much less create, a microchip?

The sum of human knowledge is proportional to the number of brains that hold parts of that knowledge. Fossil fuels gave society as a whole an immense amount of free time to explore the universe, understand it and create a body of knowledge.

In the future, as in the past when human populations were much smaller, the sum total of human knowlege will be proportionally smaller, at best. I say "at best" because that smaller population will have minimal free time. They will have more important things to do than reading books and doing science, things like growing or gathering food and protecting themselves. The vast bulk of current human knowledge will disappear forever. Some might even say "good riddance".

Hi Joe,

That is a very good point that I didn't think of! We can think of books as "ROM" (a computer's hard disk), and human brains as "RAM" (working memory when the computer is switched on). In order to work with knowledge, it must be "uploaded" into a cloud of human brains where it turns into practical know-how.

Certain complex know-how is like a program that uses a lot of memory: just think of the many thousands of brains dedicated to making computer chips, all the way down to the guy mining the silicon.

As you suggest, fewer people in smaller networks—each with less spare time—translates into less available "RAM." (And a lot of the remaining brainpower will be consumed in locally duplicating basic manufacturing and other processes as supply-chain centralization unwinds.) The result is the practical loss of much knowledge, even if the books are preserved.

Really excellent point. Thank you.

Culture is the strongest mechanism of adaptation that evolution has ever invented. Although there are other species that also possess some kinds or forms of culture, the power of his adaptative tools are limited by the amount of energy that they are able to empower it; ultimately, these limits are dictated by his physical body. Humans are the only species that possesses the ability to use extrasomatic energy, so humans are the only species able to power culture adaptation beyond the limits of the muscles.

Fine starting point. Now what happens when the exosomatic energy balloons to 100x the biophysical value, persists for enough generations to utterly change habits and expectations, then goes away? Instead of limits dictated by the physical body, our limits will be imposed by what nature can supply. Big adjustments on the way…

Bye extrasomatic energy, bye bye superpowers…thanks for this great article Dr. Murphy

Even industrial processes that COULD be done with renewable energy will not be done with renewable energy until there's a cost advantage in doing so. Buyers rarely agree to pay a higher price for an intangible benefit, such as the social justice of the workplace, or the renewability of the energy. If they're spending "other people's money" (e.g., solar panels for a government building), they may feel a fiduciary obligation to get the lowest cost, technically acceptable product. If buyers won't choose responsible production, producers won't produce it. (Exactly the same argument applies to off-shore production vs. preserving domestic jobs.)

PS: It's great to see you writing again, Tom. Your years-ago post on "energy storage" is increasingly relevant.

For some insight into how things used to be done, I recommend "Caveman Chemistry", by Kevin M Dunn. It's not ALL pre-fossil fuel, but it explains a lot of how we got into the condition we're in. If nothing else, it'll teach you to light a fire without matches, and brew a powerful mead.

The early history of fossil fuel use is fascinating. My understanding is that Britain was the only place that relied heavily on coal before the early 1800s (see, for instance, this data for France: https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/long-term-energy-transitions?country=~FRA). In the US, coal didn't surpass wood as an industrial fuel until just before the Civil War, and wood continued to dominate residential heating until the 1890s (see https://us-sankey.rcc.uchicago.edu/). Edison's Pearl Street generating plant (1882) was powered by coal, but the first hydroelectric power plants were coming online at about the same time (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hydroelectricity).

So what might an alternative history without fossil fuels have looked like? Technology and science and standards of living would have developed more slowly during the 19th and especially the 20th century, but it's absurd to suggest that we wouldn't have bicycles. We would still have electricity, at least in the more affluent parts of the world. Industry would be more concentrated near sites of abundant hydropower, at least until wind turbines become sufficiently advanced. Electric cars would certainly exist, and probably would have developed more quickly, though it seems unlikely that most people would be able to afford them. We would of course have trains, powered by electricity where feasible and by wood elsewhere. Intercontinental travel might still be by sailing ship, and therefore much rarer, but we would have trans-oceanic communication lines. The world's forests would be in much worse shape than they are today. Fewer people would live in cold climates.

When would people finally figure out nuclear energy and photovoltaics? Maybe much later just due to slower economic development. On the other hand, necessity can be the mother of invention.

That's heaps and heaps more certainty about what we can't possibly know than I'm ready to swallow. Even the inventions (electrical, etc.) that were not explicitly about fossil fuels are inextricably tangled in resources made available via fossil exploitation. We can't really know, and I'm very suspicious.

I also do not hold the "mother of invention" quip to be anything like a universal truth: counterexamples abound—not least of which is no fundamentally new energy technologies invented in the last 50 years despite pressing needs from many angles, and those various energy inventions that have been around for so long cropped up well before necessity demanded.

If you can make the case that fossil fuels played some kind of essential role in the development of 19th century electrical technology, I'm all ears. But I think the burden of proof is on you. Franklin, Galvani, Volta, Oersted, Ampere, Ohm, and Henry all worked in countries where coal use was not yet widespread.

None of them built a power plant. Building such a plant requires large quantities of cement, steel etc, which have so far always required fossil fuels.

"We would still have electricity, at least in the more affluent parts of the world."

Maybe. The inventor would need to use a charcoal forge to make the copper wire for the windings. I'm not sure you can do that with charcoal, which is why our metals were so limited prior to coal.

Plus, electricity isn't a *source* of power, so all the motors would still need to rely on power from wood and waterwheels. And that doesn't achieve the energy intensity needed to melt crystalline silicon into PV panels for large-scale manufacture.

Even today, we can't use solar energy to make more solar panels.

"it's absurd to suggest that we wouldn't have bicycles"

With the lightweight alloys, lubricants, pressurized rubber tires, Schrader valves, perfectly round wheels—the bicycle truly is a product of high-temperature coal-powered metalworking.

Maybe not impossible, but at what cost in a society whose only energy sources are water, wind, and wood?

Anyway, no need to bicker: we'll all find out soon enough!

I'm no expert on historical metallurgy, but even I know that copper has been around for a long, long time.

Of course we currently use fossil fuels to make bicycles better and more cheaply. Tom's suggestion was that without fossil fuels we might not have bicycles at all, and that's absurd.

Absurd means "no evidence." To be fair, there is *a little* evidence: namely, that civilized humans were scratching about on the surface of this planet for many eons. Hundreds of millions of would-be inventors lived and died without inventing the bicycle (or any number of other similar gadgets) before fossil fuels.

That's not proof, but its evidence in the same sense that a stick of Dynamite which has sat on a shelf for years without exploding might lead us to suspect that some additional catalyzing element might be needed.

Anyway, we're all on the same team here, if there is a way to have some industry without the gas.

By "absurd" I mean it's an extraordinary claim requiring extraordinary evidence, and Tom has offered no evidence at all. That is, he has pointed to no link between early bicycle production and fossil fuels. He has merely made the chronological observation that the bicycle was invented after the steam engine. Are we to believe that without fossil fuels all technological innovation would have come to a dead stop after the year 1712? If not, then further evidence is called for.

There's a good summary of the history of the bicycle on Jason Crawford's Roots of Progress blog (https://rootsofprogress.org/why-did-we-wait-so-long-for-the-bicycle). The first two-wheeled, human-powered vehicle was invented in Germany in 1817. From what I can tell, it used the same types of wheels already found on wagons and it didn't rely on any technologies that were advanced for that time. At that time Germany was still getting much less energy from coal than from muscle power. Crawford has his own theories about why the invention didn't come sooner, but important factors were the poor quality of roads and competition from horses. The invention came right after the "year without a summer" when many horses died or were killed for food. Necessity can be the mother of invention.

Some of the improvements over the next 60 years did incorporate newer technologies: rubber for tires and high-precision metal working for bearings, gears, and chains. But again I see no link to coal. Rubber came from the Americas and was unknown in Europe before the 18th century. Metal working improved steadily over millennia and I don't see why those improvements would have stopped in 1712 without coal (although the replacement of charcoal by coke in blast furnaces did reduce costs).

If I'm missing something important, please educate me. But the only impacts of coal on early bicycle development that I can see were economic. Coal raised standards of living and made everything more affordable. So it undoubtedly sped up the development of bicycles, at least by the late 19th century. But given the chronology I've outlined, I don't see how that speed-up could have been by more than a few decades.

I recommend re-reading the paragraph that led to this discussion. It was a bunch of questions to consider, not assertions or claims. The bicycle was the most speculative of the questions, at the end, intended to really challenge the reader to question assumptions: "Would we even have bicycles?" I do not regret posing the question: it's not obvious—or at least it shouldn't be. Paths are obvious in hindsight, but we often lack the imagination to conceive of a vastly different path than the one we took, hinging on seemingly insignificant, overlooked, or even unknowable details. I can no more easily assert that we would still have bicycles than assert that we would not. Circumspect is where it's at.

And let's not forget that there will most probably be a serious population drop, but there will also be all the currently already extracted minerals available to easily "mine".

Take copper for instance, all the electrical lines will be there to be reused for probably t least a couple of centuries if not more.

Your graph is one of my favourites, if not my favourite graph of all time. It very simply gets your point across. We are on the graph and can't get off, all we can control is the peak and the downslope but given human nature and the current state of affairs in the world there will never be enough cooperation to do anything so we are doomed to "ride it out".

At our farm we have an 800 gallon water tank that we use as a swimming pool (and fire fighting reservoir). We fill it from a creek that is 50 feet vertical and about 150 feet horizontal away from it. We use a 2" gasoline powered pump. It takes 14 minutes to fill it and uses about a cup of gasoline. I can't imagine filling it without fossil fuel. I guess without fossil fuel it likely wouldn't exist anyway because it is made from plastic. It makes me think that we should worship fossil fuels rather than waste them on trivial things like "rolling coal".

Here and there in the bush you can find interesting farm machinery designed to be pulled by animals that uses all sorts of mechanical mechanisms driven by the wheels to perform various functions. It would be a major task to feed and care for the animals necessary to power your farm equipment. From what I heard from my relatives that moved here in 1905 it was more or less all work and no play.

I have a 1908 Sears catalog that I like to look at now and then to see how different people's lifestyle was before widespread use of electricity and fossil fuels. Back in 1908 the average salary was about 22 cents per hour, now it is about $22 per hour so the prices are more or less comparable if you change cents to dollars. There are loads of interesting comparisons. Anything rubber is outrageously expensive. There are two pages of whips of various types. Hearing aids are a funnel. It is even more in treating if you compare it with a 2008 Sears catalog and see how things have changed. There are some striking differences.

Regarding: "..we have an 800 gallon water tank that we use as a swimming pool (and fire fighting reservoir). We fill it from a creek that is 50 feet vertical and about 150 feet horizontal away from it.

A little off-topic. When I was a teen we lived on the west bank of Kinderhook Creek. Across the creek was a farm, on a small bluff (perhaps 50 feet) and, upstream (150 feet?) a small brook. A stupidly simple device -a hydraulic ram pump- was in a concrete hole near the brook, fed by a long pipe from higher along the brook. Perhaps 20 feet higher. I never located the water inlet.

It was long dead when I was there.

A ram pump features a large pipe, paralleling a stream, with a swinging shut-off valve. When the valve slaps shut the moving water is forced into a smaller delivery pipe and up a considerable height -in this case to the barn on the bluff. The following pressure drop allow the valve to open again. And it repeats…

That is a really interesting system and will likely be widely used once fossil fuels run out. My problem is not enough driving head for a hydraulic ram pump to work. The creek has a low slope (and flow) and in order for a 50 foot delivery head to be possible you would likely need a 5 to 10 foot driving head which would involve a very long piece of pipe and a small dam.

I'm coming to three (of many) rather 'anxiety-provoking' conclusions given everything. First, that our leveraging of that one-time cache of fossil energy has expedited our journey into ecological overshoot–this being our fundamental predicament that is signalling its presence in all the 'problematic' symptoms we are experiencing.

Second, our penchant for denial of anxiety-provoking situations is leading us to ignore our predicament and cling to optimistic narratives–even if completely false in nature.

Third, our ruling elite are themselves leveraging our 'fears' to do what they do best: seeking to maintain/expand the power/wealth structures that exist in complex societies and provide them their privileged positions; and our tendency to defer to 'authority' and desire to alleviate anxiety make us susceptible to the narratives they create, such as human ingenuity and technology will allow us to continue to chase the perpetual growth chalice to infinity and beyond.

The collapse that always accompanies overshoot seems baked in at this point with little if anything we can do about it.

Personally, I'd like to see our dwindling fossil fuels dedicated to decommissioning safely those significantly dangerous complexities we've created (e.g., nuclear power plants, biosafety labs, chemical storage, etc.) and relocalising as much potable water procurement, food production, and regional shelter needs as possible rather than attempting to sustain what is ultimately unsustainable given the fossil fuel inputs necessary. Perhaps, just perhaps. by doing these things a few pockets of humanity (and many other species) can come out the other side of the bottleneck we've created for ourselves.

This article has got me thinking hard about exactly how the suit will come off. It seems to me that we can best visualize the process as a series of games of "musical chairs":

(a) International. Whole regions (such as most of Africa) will be cut off from fossil fuels relatively early, as prices are bid up to levels they cannot afford. What economics does not accomplish, military force will, with strong nations securing preferred access.

(b). Regional. Even in strong countries, regions will slip into post-industrial poverty (such as much of Scotland and the North of England, which are already in a decidedly Second World state) even as centers like London remain strong.

(c). Local. More and more households even in wealthy cities will find themselves destitute as they are dropped one-by-one from the economy (such as the increasing numbers of formerly middle-class people living in campers parked along the sides of highways in California). You might say, "Collapse visits one household at a time." Extreme poverty of the type not seen for a century will slowly become widespread.

Implications:

(1). Loss of critical mass for certain technologies. Some things rely on mass-adoption to be cost-effective. For example, the per-item cost of automobiles will rise if fewer people buy them (causing demand to further spiral down). In the same way, the present highway system will cease to be cost-effective without many millions of drivers paying gasoline taxes.

(2). Shrinking (but persisting) islands of strength. There may remain some cities with functioning skyscrapers and subways long after other places (e.g., Detroit) have entirely lost their commercial districts.

(3). Ineffective central governments. Before democracy fails, the overpowering incentive will be for the poor and unemployed masses to vote themselves money and resources, thereby stripping the central government of surplus resources and leading to a bankrupt and dysfunctional state. As wealthy regions feel increasingly put-upon, they will tend to break away into semi-autonomy (much as the wealthier cities and provinces along the coast of China have been for most of history).

(4). Mass migration. As regions experience famine, we can expect to see mass migration on a scale never before imagined. (We may get a preview as soon as next year, when many African and Middle Eastern nations who relied on Ukraine for 100% of their grain supply begin to experience famine.) Such huge migrations may swamp certain areas (perhaps much of Europe) that otherwise could have persisted as islands of strength.

(5). Surplus male population. It is a matter of survival for nations to find something to do with unemployed young men, lest they become violent. When all else fails, a "foreign legion" is the go-to option (essentially a "hero lottery", bestowing winners with pensions and the social status needed to find a mate). The international struggle to secure access to the remaining sources of fossil fuels will provide much for them to do.

Good news: The best news, perhaps, may be that industrial civilization will continue in pockets for much longer than we might expect. This will allow scientific research to continue into how to adapt our technologies for an era of less fossil fuels.

Great summary Jason. Have you blogged / published thoughts like this elsewhere?

Hi halfhog,

Thank you for the kind word. To answer your question: I haven't blogged, nor do I comment elsewhere. Credit to Dr. Murphy for getting our creative juices flowing!

When I was a college freshman back in 2005, I attended a talk in a community conference room by Dr. Chris Martenson, who laid out the basic problem: exponential growth on a finite planet (since explored in more quantitative depth by Tim Morgan of Surplus Energy Economics), with particular attention paid to debt, energy, and non-renewable resources. Since them, I've been attentive to thinkers on this subject, from James Howard Kunstler, the blogger and novelist who seeks to bring the post-fossil fuel world to life, to John Michael Greer who has deeply pondered exactly how energy-deprived civilizations decline, and how our collective vision of the future must change.

Of them all, Dr. Murphy is the only one I've encountered who is inclined to keep himself focused on the problem (or predicament, as it were) at the population level, and its implications in quantitative terms. That's perhaps why Dr. Murphy's blog is the only one which inspires me to comment.

Thanks, Jason, for both contributing constructive comments (I'll add to the encouragement to blog about it) and for placing me in good company. I'm not sure how well I will continue to satisfy the attribute of staying focused on the quantitative predicament, despite my history, blog name, and textbook theme. More and more I find that I am wading into the slippery goop of morals and philosophy. As a physicist, I have looked askance on these fields. But I tell myself I came to them honestly.

I guess the physics and quantitative approach convinced me we have a mega-scale predicament. Exploration of technological solutions suggested that technology is no solution. Increasingly, I find greatest comfort in the indifference of nature, seeing humans as caught up in a flow and guided by forces more powerful than they (we) are, but recognizing that the only hope in breaking out is via values, expectations, and humility. Thus the unfortunate migration from physics to philosophy. Still has a bad taste, and not sure I should expect it to improve.

Dear Tom,

Thank you for the kind word, and for this blog!

" I'm not sure how well I will continue to satisfy the attribute of staying focused on the quantitative"

I think it's time to go there, by all means. I should clarify that it's your approach and your frame of analysis that I think is highly unique and valuable. Like staring at the sun for too long, many people don't seem to like to remain focused on the meta-predicament itself, and instead veer off into things like horse-race economic commentary, survivalism, or fatalistic philosophizing.

"Still has a bad taste, and not sure I should expect it to improve."

Perhaps, in some sense, science is at its best when it inspires us to contemplate who we are, and how we must change.

"humans [are] caught up in a flow and guided by forces more powerful than they"

Indeed they are, as they stand on the frontier of a new age, and in the twilight of the old. As the poet said: "Neither crown nor coin can halt time's flight, or stay the armies of the night. King and villain, lad and lass; all must answer to the hourglass."

Assuming we are actually 1/2 way through our fossil fuels, oil in particular, we are WAY past the 1/2 way point of the fossil age. More than 1/2 of the oil ever produced was produced since 1990. We use WAY more oil than we did 100 years ago.

But that is not really the important point. The important point is we are producing MUCH lower EROI oil than we used to produce. We naturally high-grade and took all the best stuff with the highest EROI first. The first wells produced tens if not hundreds of thousands of barrels of oil using a a few barrels of oil equivalent in materials. The deposits were close to the surface in accessible areas and under high pressure with little incursion of water and other contaminants in the producing pockets. For every barrel of oil equivalent we spent, we got well over 100 in return. We are nowhere near 100 to 1 today and the further into the fossil future we look, the lower the EROI will be. At some point it will be far too valuable to burn. It will be a large energy sink. Only the wealthy will be able to afford plastics.

If solar panels pay for themselves in energy terms in 7 years, we got a 4 to 1 EROI (assuming they last 30 years, a large assumption on our part. No Chinese panels are that old) . That will not power civilization. If we have to build so many more solar panels to generate enough electricity to power civilization, the energy industry would be 10-100 times larger than it is now. That would make it more expensive. Energy is so cheap because we have to pay so few specialists to work in the energy industry.

I am curious about the EROEI implications for PV – the key phrase seems to be: "That will not power civilization". Perhaps.

Solar panel EROEI is based on lots of assumptions and our current economic structure. Perhaps manufacturing will contract, become localized around good sources of the dominant raw materials instead of monster mines leading to monster train lines and supertankers supplying insanely concentrated production lines etc. PVs and glass fabrication are less high-tech than cutting-edge billion-transistor ICs with sub-10nm feature sizes and most inputs are fairly abundant. They aren't limited to mono or polycrystalline or even silicon. So perhaps we'll focus on designs that are more durable or require less highly refined inputs. Maybe we'll even repair panels and ride bicycles to work.

That last line signals perhaps the much bigger challenge of when/how do we start giving stuff up and who decides? Will we ration fuels to slow down environmental collapse and provide more for developing countries? At the moment everyone's moaning about gas prices and the Russia-Ukraine war and I assume most parents want their kids to have a survivable world, and yet it seems the only proposed solution is "EVs" and maybe less plastic bags and straws. How about lower speed limits, rationing, banning or greatly restricting luxury activities like cruise ships, car races, flights. We had all that and more to fight wars and accepted it – are we going to wait for undeniable environmental collapse before considering similar moves?

"Will we ration fuels to slow down environmental collapse and provide more for developing countries?"

This is fantasy land. NOBODY is going to give up material wealth so that "developing countries" can get richer. That is out of the cards, thank gods. Only really comfortable people could even entertain such a thought.

"and yet it seems the only proposed solution is "EVs" and maybe less plastic bags and straws. How about lower speed limits, rationing, banning or greatly restricting luxury activities like cruise ships, car races, flights.."

People didn't come up with this on their own. This is what our rulers want us to believe.

I don't think you appreciate how much power electric vehicles use and how much "renewable" electricity sources we would have to find and utilize to not only run the rest of society, but to charge all these cars. We are not going to repair solar panels, at least by any reasonable definition of "repair" The closest to repairing we are likely to achieve is breaking panels down to the cells and "recycling" the bad cells and making fewer used panels minus the bad cells. How long would such refurbished panels last before they would again suffer a failure and need this refurbishment again?

Imagine you wanted a run a mine on solar panels. You would have to install as much solar capacity as could be generated on the shortest day of the year, at least 3 times over to keep it running 24/7 and have an energy storage system. Of course, you would need to expand that even more to smooth out the cloudy or rainy days. This is one the reasons it would be so expensive.

The EROI is just too low. A 4 or 5 or 10 to 1 EROI world just looks a lot different than a 30 to 1 world (30 to 1 is the estimate I have read for the EROI of the average barrel of oil). Plus, the entire solar grid needs to be replaced every 30 years, at best. The mine example extrapolates to society at large. The cost will be astronomical.

Without fossil fuel, think of how many people will have to go back to farming. 80-90% of people used to be farmers before fossil fuels. We are SUVs. Modern agricultural is where 2% of the people produce all the food using fossil fuels to turn soil and sunlight into food.

What all this and more boils down to, is we are not going to run the existing civilization on solar panels and wind farms.

“Assuming we are actually 1/2 way through our fossil fuels, oil in particular, we are WAY past the 1/2 way point of the fossil age.”

The Seneca cliff. That’s good news, I think. The best humanity could hope for would be a relatively quick, relatively sharp end to the fossil fuel age. If we could manage a really epic collapse, so much the better for our posterity.

As Ron Patterson says, “We will not hear warnings of impending disaster and act. We will wait until the disaster is upon us then react. It is simply in our nature to behave in such a manner. And then we will eat the birds out of the trees.”

“Eating the birds out of the trees” implies burning all available biomass and generally stripping the ecosystem from end to end looking for the last resources to feed a starving planet.

The longer that process goes on—and the more slowly the fossil fuel Band-Aid comes off—the more destruction we will do.

Only half joking: do your great-grandchildren a favor and buy a Jet-Ski. Fossil fuels are now a poison.

As for the wastefulness of "auto racing" (mentioned above), it seems likely to me that EVERY mass spectator sport needs to address the fuel consumption of the spectators, not just the main event. Tens of thousands of people drive, and fly, great distances to each football stadium, hockey rink, basketball court, and baseball field, all over the country, throughout the seasons. And they patronize hotels and restaurants along the way, activities which are welcomed by the local businesses, but are also more energy intense than quietly staying close to home.

Here’s a left-field perspective that I am trying to get people to chew on: burn that oil!! Oil is not our friend. At this point, it is a poison that is destroying us and the planet. In our dreams, where humans are capable of responsibly stewarding remaining supplies, then we should conserve it. However, unless humans stop acting like humans, then the faster we burn it—or better yet, launch it into outer space—the better it will be for our posterity.

This is only because a long period of slowly declining fossil fuel supply would be the very worst scenario both for us and for the ecosphere, IMO. See my previous comment (directly above) for details.

Fortunately, humans are studiously following my recommended plan 🙂

Thoughts?