I seem to love asking questions that can’t be answered definitively. Yet, attempting to do so can yield useful insights. I am gearing up to post a sizable piece about whether we can expect modernity to last, but realized that it would probably be a good idea to first take a stab at defining modernity, and to explore whether this phase in human history basically had to happen.

I seem to love asking questions that can’t be answered definitively. Yet, attempting to do so can yield useful insights. I am gearing up to post a sizable piece about whether we can expect modernity to last, but realized that it would probably be a good idea to first take a stab at defining modernity, and to explore whether this phase in human history basically had to happen.

Perhaps not surprisingly, I lean toward the conclusion that modernity was inevitable. My position is reasonably strengthened by the observation that we are, in fact, where we are. It would be much harder to argue the counterfactual that modernity was unlikely, and simply wrong to say that it could not have happened.

I am finding that a number of people reject any application of determinism to human affairs—the insulting notion that we might be subject to dynamics beyond our awareness or control. As with many things these days, I tend to suspect such reactions as stemming from a sense of human supremacy: “surely we humans have transcended base forces and bring full agency to all that we do…” I, however, am perfectly comfortable seeing humans and cultures caught in a current, so will proceed on those grounds.

In its broadest sense, we might say that the biggest discontinuity in human ways is between hunter-gatherer mode and agricultural mode, as permanent settlements, cities, and nations only become possible in an agricultural context. From this high perch, “modernity” might be interchanged with “civilization,” and therefore extend to earlier times, while those on lower branches might conceive that modernity started with televisions or smart phones. You can’t please everyone. One thing I have noticed is that people seem to be somewhat willing to accept the notion of modernity’s end, but react more strongly to the notion of civilization’s end. So some distinction lurks in the minds of people between these two—probably in how far back we would have to set the clock upon modernity’s failure (1980 isn’t so bad, but 10,000 years back? Eeek!). I will use the term modernity throughout, but personally am willing to substitute civilization much of the time.

The term “anthropocene” is often used to describe the modern age. This is meant to delineate a new geological era dominated by the presence of humans on the planet. The idea has definite merit, given the overflowing presence of humans on the planet and our devastating impact on climate and biodiversity. My main beef with the anthropocentric term is that I wonder if it makes sense to give an era (or epoch) name to something that may be over as quickly as it started. We don’t have a name for the era between the Mesozoic and Cenozoic marked by the chaotic period in the aftermath of the comet impact 66 million years ago. Likewise, this disruptive moment may simply delineate two eras, while the disruption itself is brief enough to appear like the thin black layer in the rock between two periods. In any case, this post will partly lean on this human-dominance aspect in assessing inevitability.

Defining Modernity

In establishing what we mean by modernity, a real scholar might diligently comb the literature for previous definitions and perhaps synthesize some coherence out of what is bound to be a heterogeneous mess. But where’s the fun in that? Let’s see what we can do shooting from the hip.

First, let’s agree that modernity is happening now, as opposed to calling the present “post-modern.” After all, in setting up to evaluate if modernity can last, it would not serve to define modernity as a philosophical phase that already ended some decades ago. That’s not where I’m coming from. Whatever definition we make, I want it to include the present, but also be capable of stretching back toward its origins centuries ago. It might help to think in terms of a lifestyle many would call “Western,” which at this point can be found practically anywhere on the globe. We might propose a starting point as:

- Modernity is the dominant style of human life on the planet today.

- Modernity is a period of human domination of the biosphere.

- Modernity is a mindset, or a worldview, placing humans at the apex of “creation” and marked by a quest for control and mastery.

Here, we see some of the complexity, in that modernity can be spoken of variously as a lifestyle, a time period, or a mental framework. All are relevant. I recommend embracing the multi-dimensional quality of the term.

We ought to pause to acknowledge that not everyone willingly engages in modernity, and not everyone benefits. But hardly anyone (of any species) evades being impacted in some way.

Let’s try to build a list of modernity’s attributes. These aren’t definitive or in any particular order—just a first attempt. Each item should sound familiar in describing the way modernity operates today.

- Feeds its population almost exclusively via domesticated—often industrial-scale—means (i.e., agriculture and livestock vs. hunting and foraging).

- Has a high energy metabolism, far exceeding the biological metabolism of the participating humans.

- Conducts (and relies upon) global trade/exploitation.

- Employs a market-based economy (using money, as opposed to gifts, barter, or exchange).

- Characterized by growth in market size, population, and/or technology.

- Has a high material throughput, from mining to disposal.

- Uses sophisticated devices, like electronics or elaborate mechanisms whose constituent parts no longer resemble items found in natural settings.

- Characterized by a sense of defying limits and transcending our animal nature: becoming “gods” of increasing capability and dominion.

- Results in a steady decline of biodiversity and ecosphere health as the metrics of modernity swell.

If I did this right, then all of these describe the present state of modernity, but would not as easily apply to traditional Indigenous ways of living, or to the ways of plants and most animals on the planet (some do practice agriculture). I was deliberately careful about technology, as many other animals make and employ tools. I sought a rough dividing line between the kinds of stone-and-wood tools of prehistory and “modern technology.”

Optional Elements?

So here’s the thing: while it may be possible to maintain modernity without one or a few of these items (which are not independent, by the way), we know that these elements are a part of modernity. We lack evidence that modernity functions without having all of these in place.

We also don’t know if any of these elements are tolerated by the planet for the long term. We know that their absence in human cultures were tolerated for hundreds of thousands of years. Their introduction over the last few millennia kicked off an accelerating experiment that hasn’t really been around that long and may soon self-terminate due to spiraling ecological harm or other planetary limits.

Long-term Compatibility

What I am ultimately interested in is identifying activities that can be maintained indefinitely. I think it is obvious to most people at this point that the present prescription won’t cut it. Lots will have to change if we want to keep a livable ecosphere. For many, this awareness is primarily associated with climate change. Clearly, cooking the planet is an unsustainable plan, but would elimination of fossil fuels in favor of renewable energy technologies solve the problem and allow a continuation of modernity? Is modernity itself capable of persisting, given the right technologies? As I’ll elaborate in the next post, I would say: no.

In the end, anything that mounts cumulative damage to biodiversity and ecosphere health is probably out of bounds. Most, if not all, of the items on the list above answer “guilty” on this count—unless they have lawyers. Thus, all of the elements are potentially problematic (more on this in the next post). Even eliminating any one of these might cripple modernity, but if all are problematic, well…modernity does not stand much of a chance.

Pre-modern technology

What about earlier technologies, like fire, arrowheads, stone axes, etc.? Where is the line between technologies that are okay vs. not okay for long-term living on the planet?

It is possible that all of these are over the line, ultimately—that Homo sapiens crossed the line in evolutionary fitness by becoming too intelligent to remain a viable species in the long term. Maybe any species able to wield fire and axes will eventually overwhelm the community of life and fail via its own “success” by triggering ecological collapse.

Well, if that’s true, then so be it: nothing for us to do except ride out the evolutionary game in shame. But I’ll operate on the more hopeful assumption that humans are capable of long-term life on the planet, bolstered by evidence from the distant past. The ecosphere is never in equilibrium, but until the dawn of agriculture, human impacts on the planet were slow and largely accommodated by the rest of the community. Yes, megafauna extinctions cropped up as a result of migrations into areas that did not experience co-evolution with humans. But that’s part of what can happen in the great game, by the usual rules. Humans are not unique in this sense.

Eliminate One?

If I had to pick one item to eliminate on the list above in order to achieve a sustainable existence, it would be the sense of human transcendence (supremacy). Armed instead with humility and a respect for limits, we would either automatically eliminate other items on the list—seeing their folly—or we would approach such things in utterly different ways, cognizant of their negative impacts. Would (or could) the result still resemble modernity? It’s hard to say, but I struggle to see it. This would be a world of deliberate restraint, of aversion to exploitation of the natural world. Can one have a smart phone in such a world? Or does the only route to a smart phone run through an exploitative disregard for the natural world? Again, we lack evidence to suggest it could be otherwise. And while it’s no great feat to imagine something might be possible, practical reality may express its own opinion.

Inevitability

Let’s now turn to the question of whether modernity had to develop. For me, the start of agriculture marks the most important break with earlier ways, setting the stage for modernity. I say this largely because of the speed with which things changed once agriculture had taken root. It took only several thousand years for the “technology” of agriculture to explode into modernity, whereas fire, for instance, has been used by humans for over a million years without a similar result.

Was agriculture itself inevitable? The fact that it started independently in various regions during the most recent period of post-glacial climate stability says something. Also, humans have always had a close relationship to plants, from which all nutrition springs. Humans are observant creatures, and have long known what seeds do. So it seems bizarre to me to think that no humans would eventually experiment with agriculture and elaborate it to the stage where most nutrition came from that channel.

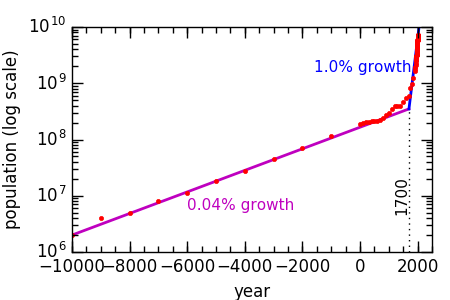

Once agriculture started, human population began a slow, inexorable climb. A look at population history on a logarithmic scale stretching back to 10,000 BCE shows an exponential phase characterized by a modest 0.042% annual population increase—corresponding to a doubling time of roughly 1,700 years. Incidentally, the rate until 10,000 BCE would need to be at least 10 times lower in order to extend back 200,000 years. So the 0.04% post-agricultural rate represents a dramatic step up, modest as it is by today’s standards.

Projecting the line forward in time, skipping over the developments of the Enlightenment and fossil fuels, the trend would have eventually reached 8 billion people around the year 8800.

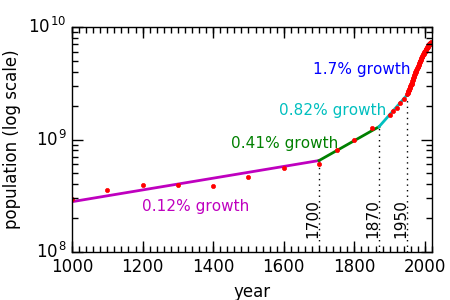

A closer look at more recent population history breaks into separate exponential segments characterized by eras of city-states (magenta), the Enlightenment (green), fossil fuels (cyan), and the Green Revolution (red). (These figures are from Chapter 3 in my textbook, for additional context.)

Extrapolating the line fits (representing exponential curves on a logarithmic scale) results in crossing 8 billion at ever-sooner dates.

| Era | Rate | Reach 8 Billion in year |

|---|---|---|

| Agriculture | 0.042% | 8800 |

| City-State | 0.12% | 3800 |

| Enlightenment | 0.41% | 2300 |

| Fossil Fuels | 0.82% | 2090 |

| Green Revolution | 1.7% | 2020 |

The point I want to make is that even without the advances of recent centuries, population growth was on track for human domination of the planet (thus, large scale ecological harm) in a time that is still short compared to the duration of hunter-gatherer humans on the planet. Agriculture lit a fuse. The various advancements in more recent times simply accelerated the process—dramatically.

Extrapolations are fun and all, but could human population have ever actually reached today’s scales and lifestyles without the more recent developments? Maybe not, but here we come into other facets of inevitability. Once agriculturally-based populations are large enough to form cities, why wouldn’t some try it? Now we’re caught up in the river’s current. One thing leads to another. Armies conquer. The powerful agricultural city-state model expands. Empires form. A few clever, observant humans among hundreds of millions, freed from daily subsistence toils are inevitably going to stumble onto some pretty cool discoveries and systematize them into science. Someone will find novel applications for that black rock that burns hot. How would such developments have been prevented across all times and all places? Had Newton been killed by the apocryphal apple, we’d still have a law of universal gravitation from that time period, just bearing a different name. Independent, virtually identical developments happened roughly simultaneously throughout the Enlightenment, and continue today.

I think of the process on entropic grounds. An ensemble is free to explore all energetically-possible states. It’s how we learned the uses of various herbs and medicinal plants: people try stuff. It’s not purely random, though, like monkeys accidentally banging out Hamlet. Advantages are kept, and disadvantages discarded in a systematic process that self-reinforces.

Modernity without Fossil Fuels?

Given this framework, I would say that the employment of fossil fuels was essentially inevitable, given their availability. But what might have happened had Earth not been endowed with fossil fuels? Would we still have modernity?

The list above does not explicitly rely on fossil fuels, simply stipulating an energetic metabolism far in excess of the biological metabolism of humans. Draft animals already began the journey down this road, but fire, charcoal, wind, and water were being harnessed to facilitate the manufacture of metals and elaborate machines, global trade, food production, and lots more.

Obviously, I would be foolish to claim that we would have reached the same place by other means, and certainly not as quickly without fossil fuels. But the essential ingredients may still be present for continued expansion and development. Most importantly, as all these advantages tilt in the direction of human habitation and expansion, I could easily expect the toll on biodiversity and ecological health to eventually reach a breaking point—even if it took a few more centuries to manifest. But what is that on the timescale of evolution or human presence on Earth? Unless societies around the world founded themselves on ecological principles (spoiler: very few did, and those who did were overpowered), how would accumulating harm have been avoided as the human footprint expanded and expanded?

Of course, we do have fossil fuels, and the effect has been to super-charge modernity and create a population surge that puts the entire planet in danger.

Conclusion

Was modernity inevitable? We could play a lot of “what if” games: what if fossil fuels were not generated on Earth; what if the stability of the Holocene had not presented itself; what if humans had not evolved; what if the comet had not hit Earth and killed off the dinosaurs? While I poked into the first question above, I’m most interested in the world as we find it: one with humans and no dinosaurs; one enjoying a stable climate period; one loaded with fossil fuels. Given that particular chess board, is something like the game we see playing out around us essentially inevitable? I tend to think so.

Last week, I presented a reaction to the Graeber & Wengrow book The Dawn of Everything. The authors would certainly reject the argument for inevitability. To them, evidence pointing to a great diversity of experiments indicates no single prescription and a wide-open frontier of ways it could have been. As I pointed out, they neglect interaction and “game theory”—by which I just mean all forms by which one system might influence another in interaction. Strategic advantages (e.g., guns, germs, and steel—but also food production, hierarchical organization, and even philosophical grounding) can heavily influence which system prevails over the other. A stunning diversity of arrangements might be tried, but they don’t all get to survive to define modernity.

This post set out to do two loosely related things: 1) define the essential ingredients of modernity; 2) explore its inevitability. Surely for some I have failed on both counts. That’s okay. To me, this is not a left-brained game of literal, technical exactness. Operating wholly in that space is unlikely to yield useful insights in this context. I invite readers to absorb the spirit of the arguments and muse upon the matter for themselves.

In this sense, the modern era has a number of attributes that differ substantially from what came before agriculture, civilization, and modernity. What came before lasted for a very long time, and may have been sustainable—at least far more so than what we have now. The current system appears to be running off a cliff, which is by no means a consensus observation (its own source of concern). Therefore, it is important to attempt an approximate delineation—however crude or imperfect—between modernity and its more sustainable predecessor.

It may well be that given the initial conditions a few million years ago, something like this was bound to happen. Whatever the case, we’re here now. In the next post, I will explore how important some of the items on our list are to modernity’s continuance, and evaluate whether our present arrangement seems likely to persist.

Views: 3461