Readers may have noticed that I’m on a bit of a demography kick of late, and this post is no different. Several reasons contribute to this focus. First, human population is an extremely important factor in the future health of this planet. Second, I am fascinated by the prospect that population growth may not turn out to be as crushing as I had previously believed. Third, having developed a tool for demographic projection, I want to get my money’s worth before scooting off to something else.

The first post in this series examined the unexpected realization (on my part) that current trends could put us on track for a global population peak in the next few decades—maybe deflating the population balloon before something pops. In the process of investigating how this squared with most projections that show a late-century peak, I came to understand the theoretical biases—especially in fertility—employed by United Nations demographers. This first post also explored possible implications of an early peak: how modernity would cope with such a major, unprecedented, and rather prolonged period of declining population. The second post sketched out a reasonably sophisticated demographic propagation tool I constructed tracking six regions of the world so that I might reproduce the U.N. projections and explore what I considered to be plausible variants in terms of both fertility evolution and survival/medical trends. I also wedged in a bonus post exposing the repeated systematic failure of demographic projections to capture recent rapid trends in declining birth rates. The models apparently don’t incorporate whatever drives this major phenomenon.

In this post, I examine a few implausible scenarios for the purpose of isolating and better understanding factors at play. I think of it as answering “What If” questions (calling to mind Randall Munroe’s excellent What If series of outlandish yet illuminating questions). What if fertility around the globe suddenly locked at the replacement value? What if things stayed exactly as they are today? How much earlier would population peak if Africa’s fertility fell as rapidly as other recent precedents? What if we suffered a pandemic or global resource war?

The first few of these explorations are not intended to be realistic as much as they are illustrative of the relative importance of various factors. I learned from the exercises, at least, and hope you will, too.

Replacement Plus Pyramid?

Before firing up the full demographic propagator machinery, let’s address a basic question that wasn’t obvious to me. What if a population having a strong demographic pyramid shape (young-heavy) suddenly began practicing replacement rates of reproduction. Would the pyramid shape force continued growth to produce ever-more babies despite operating at replacement rate?

Each year, as the original pyramid advances in age, more women occupy the child-bearing range so that more babies are born each year, even at “replacement” rates. Thus the infant population grows year by year and that growing cohort will ultimately reach child-bearing age themselves to keep up growth via childbirth. What I am describing is no more than the demographic inertia concept, but the question is whether the inertia from a steep pyramid is enough to preserve indefinite growth even if nominally at replacement fertility rates. Like I say, it wasn’t obvious to me just by thinking about it. Post-simulation, it’s now obvious (thanks, hindsight!).

To explore, I start with a linear population pyramid (in women) then instantly impose replacement: 1 female baby per woman, spread across reproductive years. I keep it clean by ignoring mortality through age 50. I only (need to) track female population for this exercise (males will also be produced in a 1.07:1 ratio, so that replacement TFR in the absence of mortality concerns is 2.07). I artificially arrange the pyramid to have 50 women at age 49, 51 at 48, and so-on until reaching 100 infant girls at age zero (prior to first birthday). I use the age-specific fertility distribution presented in the table in last week’s post (for the U.S. in 2017). The results don’t depend critically on the distribution as long as childbirth is spread out over an age range, but I wanted something at least representative. What I plot is the number of infants born each year as a function of time, which is effectively the population pyramid on its side; older to the left.

The plot starts out with the initial linear pyramid (for the first 50 years), then has a sudden reset downwards as the replacement fertility rule is enacted. Just after this reset, the number of infants each year resumes linear growth based on the fact that the age-bearing population expands linearly as the pyramid moves into maturity. When the first major infant dip reaches child-bearing age 15 year later, the linear increase begins to turn over, eventually declining and kicking off a decaying oscillation that settles out to a stable value. The black feature at lower left is the age distribution of child-bearers at time zero (applying to the initial linear pyramid portion), which effectively slides to the right as the simulation runs.

So: replacement ultimately settles things, despite the inertia caused by the initial pyramid. The key to overcoming inertia is the sudden reset (huge and unrealistic in this contrived case), pulling the rug out from under the high fertility rate that was responsible for creating the pyramid in the first place.

Incidentally, keeping the linear ramp going, so that 101 female babies succeed the 100 in the prior year, requires a TFR of 2.94. But the next year would require a small drop to 2.93, followed by a continuous (and nonlinear) drop to maintain this artificial linear structure. Without the continuous drop in fertility, the result would be a predictable exponential progression.

Baseline Reminder

Last week, I presented essentially six model outcomes based on two regional fertility trends (that imagined by the U.N. and my own creation) and three survival trends (U.N.’s optimistic ever-better; locking at 2023 values; a slow reversal in mirror fashion). For the purposes of this post, I will present results of the most extreme differences in this set to establish a semi-plausible range of possibilities, but breaking out by region this time (as defined in last week’s post). Each cell contains three numbers: year of peak; peak in billions, and billions remaining in 2100 (this last number being highly dubious, as the model surely fails in all sorts of ways in a post-peak world).

| Scenario | Africa | Asia | Europe | Latin | N.A. | Oceania | World |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| U.N. | 2100 3.84 3.84 |

2056 5.32 4.70 |

2022 0.75 0.58 |

2055 0.75 0.64 |

2094 0.44 0.44 |

2100 0.07 0.07 |

2084 10.38 10.27 |

| My TFR | 2064 2.17 1.58 |

2034 4.90 1.96 |

2021 0.75 0.27 |

2035 0.70 0.32 |

2037 0.40 0.26 |

2055 0.06 0.05 |

2040 8.66 4.44 |

In this and tables to follow, a “peak” in 2100 really means that the simulation had not yet found a proper peak when terminating at the year 2100. This is the case for Africa in the U.N.’s model, which would peak at 4 billion around 2130 according to my demographic propagator. Hmmm: is it realistic to ever sustain 4 billion humans on that continent if considering resource constraints and not just extrapolating trends? More on this later.

For reference, today’s population in each region, in billions, is approximately as follows:

| Africa | Asia | Europe | Latin | N.A. | Oceania | World |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.49 | 4.79 | 0.74 | 0.67 | 0.38 | 0.05 | 8.12 |

Replacement Now!

The first experiment involves immediately (and rather artificially) locking TFR at a replacement value of 2.1 in three survival models (as described last week). This gets at what the current age distribution has in store, neutralizing fertility as neither driving nor suppressing growth: what does inertia alone produce based on current age distributions?

| Survival | Africa | Asia | Europe | Latin | N.A. | Oceania | World |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| U.N. model | 2100 2.04 2.04 |

2100 5.87 5.87 |

2100 0.89 0.89 |

2100 0.87 0.87 |

2100 0.62 0.62 |

2100 0.08 0.08 |

2100 10.35 10.35 |

| 2023 lock | 2069 1.81 1.70 |

2061 5.39 5.21 |

2100 0.84 0.84 |

2066 0.78 0.76 |

2100 0.54 0.54 |

2100 0.08 0.08 |

2069 9.29 9.13 |

| mirror reverse | 2053 1.63 1.17 |

2045 5.21 3.72 |

2031 0.77 0.64 |

2047 0.74 0.56 |

2100 0.54 0.54 |

2100 0.07 0.07 |

2047 8.83 6.71 |

In the first scenario, population continues to climb until at least 2100 in every region despite replacement fertility. This is due to the U.N.’s extrapolation of continuous improvement in medical care, survival rates, and longevity. The annual number of babies might stabilize, but population continues to grow by stacking more elderly people on top of the pyramid. Areas where survival rates are not as high (and historically even lower) peak and decline in the other scenarios. In this sense, Africa and Asia are jointly responsible for establishing global peak population in these scenarios.

A wrinkle here is that the way I compute survival folds in migration. Migration magnets like North America (and Oceania and Europe) can have influx outpacing attrition, which pushes peaks farther out (beyond 2100, often), if sustained.

My takeaway is that demographic inertia alone would keep population growing for at least two decades under replacement fertility conditions, and much longer if survival rates do not drop.

Lock It In!

Now we play a similar game but instead of locking TFR at a replacement value, we lock in regions to their pre-COVID fertility levels (2019 values). This leaves Africa rather high (4.4) whose resulting exponential growth overwhelms the eventual contraction in other places.

| Survival | Africa | Asia | Europe | Latin | N.A. | Oceania | World |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| U.N. model | 2100 10.54 10.54 |

2090 5.71 5.71 |

2022 0.75 0.52 |

2068 0.79 0.76 |

2084 0.44 0.43 |

2100 0.08 0.08 |

2100 18.05 18.05 |

| 2023 lock | 2100 9.14 9.14 |

2058 5.33 5.06 |

2021 0.75 0.47 |

2052 0.74 0.65 |

2049 0.40 0.37 |

2100 0.09 0.09 |

2100 15.77 15.77 |

| mirror reverse | 2100 6.15 6.15 |

2044 5.18 3.61 |

2021 0.75 0.35 |

2042 0.72 0.48 |

2054 0.42 0.36 |

2100 0.08 0.08 |

2100 11.03 11.03 |

Africa runs away with it, in an unhinged (biophysically unrealistic) manner. That’s what happens when artificially locking in a fertility rate well above replacement: exponential runaway. The rest of the world hardly matters in the end if one region sustains exponential growth. In the mirror-reverse survival case, the post-peak declines outside Africa sum to 2.3 billion by 2100, yet this is more than compensated by Africa’s growth from its present 1.5 billion.

Reality Check

But let’s get real: this model can’t likely manifest in the actual world. In the U.N. survival case, Africa itself would hold over 10 billion, which is exceedingly unlikely to happen for many reasons. Not least of which I infer from this U.N. report:

From 2016 to 2018, Africa imported about 85% of its food from outside the continent.

On its own, the agriculturally-limited and resource-constrained continent is unlikely to support even the present-day population of 1.5 billion, given its current massive reliance on imported food. Some people object to the simple equation that food equals people. How about: not-food equals not-people? What can I say: we’re biophysically-dependent beings who expire after only a few weeks without food.

More on Africa

While the U.N. seems to be systematically underestimating fertility declines in much of the world, they may be overestimating the decline rates in Africa, creating concern that the U.N. may be systematically underestimating Africa’s world-dominating population growth. Yet, something troubles me about this. Recognizing Africa’s heavy dependence on food imports, it is hard for me to reconcile the biophysical basis for the U.N.’s African projection—continuing a climb to 4 billion people while the rest of the world is in population decline. Where does the food come from, and why would a scaling-down world—likely experiencing meltdown of capitalist, investment-based economies when growth is removed—intensify efforts to feed continued population growth on an economically-challenged continent?

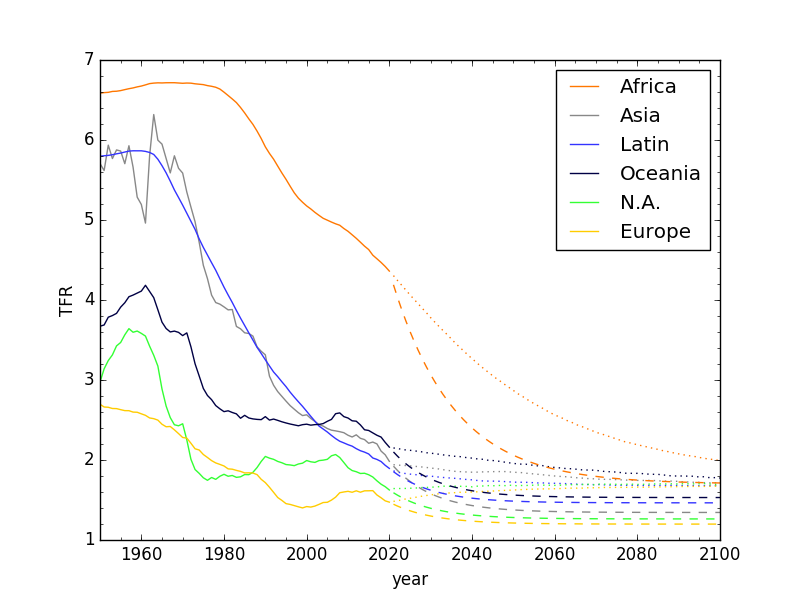

When I look at the TFR curve used by the U.N. for Africa (orange dotted line in the next section’s graph), I wonder if any such complexity is considered or if it’s just a mathematically smooth way to connect the current situation to a distant theoretical target. I am doing something slightly more sophisticated than speculation, here, as I performed decaying-exponential curve fits to the tails of the U.N. TFR projections (from 2060 to 2100), which look like this:

Solid lines are U.N. projections and dashed lines are (decaying) exponential fits. To my eye, these are perfectly decent fits, reinforcing the idea that the U.N. projections are well described by (then perhaps are generated by) a simple theory. The table below gives the fit results in terms of value achieved by 2200 and characteristic timescale for adjustment (exponential time constant).

| Region | Target | Time Constant |

|---|---|---|

| Africa | 1.78 | 31 |

| Asia | 1.67 | 39 |

| Europe | 1.69 | 42 |

| Latin | 1.68 | 11 |

| N. A. | 1.70 | 9 |

| Oceania | 1.66 | 64 |

| World | 1.69 | 48 |

Aside from Africa, the whole world magically converges on essentially the same (model-enforced) fertility rate. Indeed, fixing the target at 1.69 and re-fitting exponentials looks just as convincingly good—with the exception of Africa, which for whatever reason is allowed its own, higher target. This is part of what initially convinced me that the U.N. TFR model is largely guided by this “universal magnet” TFR around 1.69. Incidentally, I would not put much stock in time constants for trends that are already near the target value, like the Americas.

The point here is that the U.N. model for TFR evolution appears to follow drama-free smooth curves aiming for an eventual imaginary target. I put this in contrast to a systems model—like the one used for Limits to Growth—evaluating agricultural capacity and economic repercussions of post-peak regions. Ordinary models often fail miserably when the context changes. For more explicit examples of this phenomenon in U.N. TFR projections, see the bonus post about a glaring and systematic inability of U.N. models to predict or explain the present rapid decline in fertility seen around the world

A final point before returning to scenarios: of all the defined regions, Africa has the lightest per-capita resource footprint, using energy as a proxy (see Table 3.5 in my textbook). The planet cares more about ecological impact than a count of humans, so that Africa can still be rising in population while pressure on Earth has already peaked and enters a relief phase. There’s my topic for next week.

Africa Accelerates

Let’s formulate a scenario for the “earliest plausible” peak in global population. To do this, we will use the mirror-reverse survival trends and my TFR evolution that allows current down-trends to continue for a bit before settling to stability. The new feature is allowing Africa to reduce its fertility rate as quickly as some countries (and regions) have exhibited in recent decades—as something that could happen.

A look at this graph of TFR in OECD countries shows that Mexico rapidly reduced its TFR from 3.5 to 1.8 in 30 years. Ireland accomplished the same stunt in just 20 years! In this vein, I explore what happens if African TFR drops as precipitously toward a target TFR of 1.7 using a 15 year exponential time constant (taking 25–30 years to get below replacement), appearing as follows:

| Africa | Asia | Europe | Latin | N.A. | Oceania | World |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2059 1.98 1.40 |

2034 4.90 1.96 |

2021 0.75 0.27 |

2035 0.70 0.32 |

2037 0.40 0.26 |

2055 0.06 0.05 |

2038 8.54 4.26 |

In this case, Africa stays below 2 billion (compare to U.N.’s expectation of 4 billion) and peaks before 2060, producing a global peak in 2038 around 8.5 billion. Wouldn’t that be nice!

I call this 2038 peak the “earliest plausible,” but I don’t really mean that. Fertility could drop below where I have my curves artificially settle out (South Korea is now at 0.72, for instance). Global strife in the form of famine, pandemics, resource wars, and any number of other plausible scenarios could produce a peak even sooner, as we’ll see below. Decreasing agricultural support of Africa (not advocating: just acknowledging the possibility) could bring Africa’s peak even sooner than 2059. Lots of things could happen beyond our control. To this point, on the flip side, current trends could reverse under pro-natalist policies or lack of access to reproductive control, leading to an immiserating peak beyond even 2100. But as always, planetary limits may apply.

Keep in mind that the same conditions resulting in lowered access to birth control would likely be accompanied by reduced access to medical care in general, so that both fertility and mortality could rise together in such a way as to prevent another population surge. This is how Limits to Growth models typically went, which we can’t credibly condemn as being wrong.

Global Strife

Time to be not-so-nice. All the models explored so far have been gentle in the sense that survival rates have been spared any dramatic declines as may happen in a pandemic or global resource war. I don’t produce the cases that follow in an effort to be accurate in any sense, but purse these cases because I have some tools and am willing to at least peek at various consequences. Conservative bodies are politically constrained to avoid the associated unpleasantness and outcry: you won’t see this sort of thing from U.N. demographers—in part due to an immense amount of uncertainty so that a model is almost pointless.

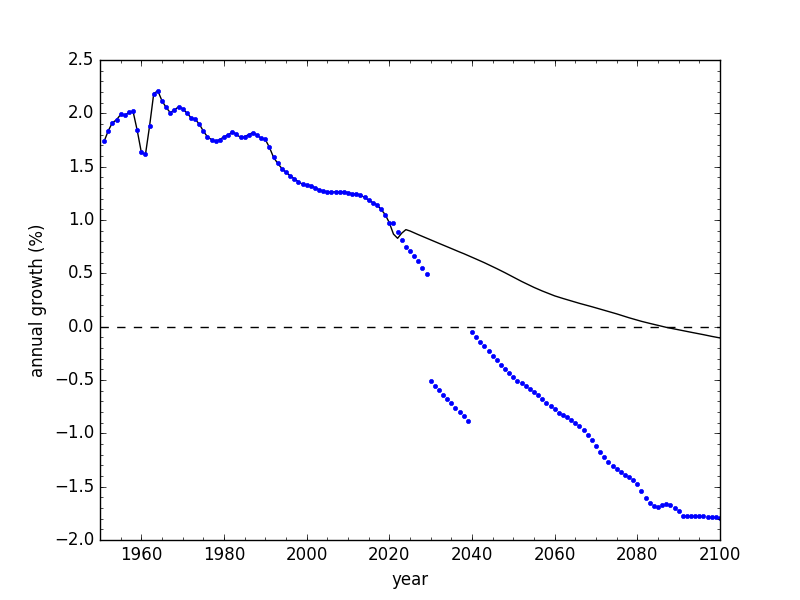

Part of the rationale is to ask: how quickly might global population peak and decline in unfortunate circumstances? As such, the baseline I choose is the TFR model above that has Africa falling fastest and others settling on moderately-low values (I could easily be accused of being too conservative here). I pick the mirror-reverse survival rate baseline, which is also probably optimistic in the midst of prolonged global strife.

Pandemic Model

For a global pandemic, to keep things simple, I initiate a decade-long struggle that each year culls 0.5% of the population, indiscriminate of age, gender, or region. It’s simple, perhaps conservative, but let’s just see.

| Africa | Asia | Europe | Latin | N.A. | Oceania | World |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2059 1.88 1.33 |

2029 4.87 1.87 |

2021 0.75 0.26 |

2029 0.69 0.31 |

2029 0.39 0.24 |

2055 0.05 0.04 |

2029 8.36 4.05 |

I honestly did not pick a 0.5% yearly attrition to force the cute coincidence that when the pandemic kicks in in 2030 it instantly drops growth to zero. Nor did I pick one-decade duration so that when the pandemic turns off it happens to restore to zero growth. But a world without coincidence would be spooky indeed. In any case, this pandemic—which is certainly not as severe as plagues of old—has the ability to precipitate an instant global peak. Maybe the next real pandemic does not last a decade, but could compensate by being more deadly than what I have assumed. Again, I am not attempting to be realistic so much as evaluating the potential scale of impacts.

What is clear from this exercise, though, is that any phenomenon impacting even half-a-percent of people per year can produce an immediate cessation of population growth that may end up producing the high-water mark. COVID wasn’t severe enough to create such a circumstance, so it would have to be a deadlier disease.

War Model

In the case of a global resource war, I assume that—similar to the pandemic—civilian casualties wipe out 0.5% of global population each year indiscriminate of age, gender, and region. Additionally, each year loses 4% of males (fighters) between ages 20–30 and 2% of males between 30–40. Like the pandemic, I begin this decade-long affair in 2030. Don’t ask me if this is realistic. It’s just a tentative peek into the unknown.

| Africa | Asia | Europe | Latin | N.A. | Oceania | World |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2061 1.83 1.32 |

2029 4.87 1.85 |

2021 0.75 0.26 |

2029 0.69 0.31 |

2029 0.39 0.24 |

2055 0.05 0.04 |

2029 8.36 4.02 |

The resulting numbers are almost identical to the pandemic case, although the decline is more evident in the plots. Note that I do not reduce fertility as soldier husbands go missing, thus underestimating the resulting decline.

Missing from this analysis is potential hardships such as famine brought on by disrupted agriculture: planting, fertilization, harvest, processing, distribution—all dependent on fossil fuels that may be hard to acquire in wartime and beyond. Also, in both of these “strife” cases, when the episode terminates, my model resumes the previous course as if nothing has happened. In reality, economic systems would be struggling, infrastructure (including cropland) would be destroyed, climate change would be worse, and ecological deterioration would be more advanced, so that we might not expect a blithe return to the previous trend. Just sayin’: lots can happen—including nuclear exchanges which could very quickly put peak population in the rear-view mirror in a less-than-desirable way.

Overall Lessons

What do I take away from these explorations? Mainly, further validation that the second half of this century could change dramatically from the hundred-plus years preceding it—in a good way. Population could be in sustained decline, damaging economic systems predicated on growth would be tattered ghosts, ecologically destructive global supply chains—including industrial international agriculture—may no longer be the norm. In these circumstances the snazzy models we bandy about today may be effectively meaningless—completely out of context.

All of this sounds tragic to the typical member of modernity—to be avoided at all costs. What’s missing from the mainstream view is that preservation of present-day human population, material prosperity, economic health (translation: cancerous growth), and all that comes with it is doomed to fail no matter what, based on the simple fact that it is intrinsically and grossly unsustainable, built as it is on a one-time inheritance of non-renewable resources and the inexorable annihilation of ecological health—all in a relative flash of time. By “inheritance,” I’m not just talking about fossil fuels. Changing the energy source does not fundamentally change the root predicament, but allows the destructive rampage (sixth mass extinction) to continue. Switching the Titanic’s coal-driven engines to solar-powered electric drive is immaterial to what the power is used to do—like ramming into an iceberg. The community of life can only take so much before ecological integrity is damaged beyond its resilient capacity and then domino failures of ecosystems produce a planet no longer able to support humans and many other forms of life. So: be careful what you wish for! Modernity cannot be long for this world. Ironically, the more “successful” it is by its deeply flawed metrics, the more certain its failure becomes.

Near-term population decline via falling fertility may be the most humane way to gift an intact world to countless lives of the future. Ideally, the 8 billion humans around today live full lives and spare future generations (not just humans) of a dismal fate by dialing things down. I hope it doesn’t come too late. Just as we may pray for rain in a drought, we can pray for a population relief valve that could even materialize without undue strife as young people around the world just say no—a laudable, unexpectedly mature response to justifiable skepticism about the path we’re on. Many things will necessarily be destroyed in the process (e.g., capitalist economies) no matter the path, but perhaps not the things that make life worth living for all.

Next post in this series on near-term population peak.

Views: 2238

Though they are highly speculative factors, I think it is important to at least consider the possible impacts of pandemic and war on population, and your analysis here does just that. As we all expected, the news is not good. We can hope for some more gentle 'natural' population relief that doesn't include disease and conflict, but as you say, it's like praying for rain in a drought.

Even so, indicators of a major sea change are already appearing. I think one such sign is the global rightward shift we are witnessing. Could it be that this is the beginning of the desperation to come, that the world's populations are sensing that something's not right, and are turning to political strongmen and their simplistic solutions? The 'supply chain problems' that we are increasingly hearing about is another sign. This common disclaimer for everything from fast food places not having lettuce to months-long waits for new cars became a popular catchphrase during the covid pandemic. The pandemic has receded, but growing availability problems persist. Aren't these so-called 'supply chain' issues really the first indications of resource depletion and economic disruption, with much more to come?

Malthus was an optimist. In imagining a continuous and smooth approach to a limiting asymptote he implicitly imagined a stable world. In reality overshoot has occurred many times in both human civilization and in natural ecosystems.

In terms of modeling human mortality, you could do worse than Gompertz-Makeham. Of which to note in Western Nations:

1. After the age of 40 mortality hazard rates (death per person-year) double every 8 years of age, this is the Gompertz component of the Gompertz-Makeham hazard rate. This exponential increase in mortality appears to be biologically fixed. There is strong basic science evidence that this is due to stochastic accelerations in the rate of aging, in accelerated failure time models. Remarkably this results in a mortality rate of 1 death per person-year at about 112 years of age. This also means there is an absolute upper limit to the mathematically expected (mean or average) lifespan in a population, of around 92 years of age.

2. Between the ages of 16 and 40 mortality hazard rates are dominated by Poisson risks, at a constant 1 death per 1000 person-years. This is the Makeham of the Gompertz-Makeham hazard rate.

3. Around puberty the mortality hazard undergoes a 100-fold logistic increase from 1 death per 100000 child-years to 1 death per 1000 adolescent-years. This is not captured by Gompertz-Makeham. This is likely due to the obvious increase in social and environmental interactions, and hence exposure to risk, that occur with puberty.

4. In the first year of life the mortality rate is as high as 1 death in 100 infant-years. This drops rapidly to the childhood mortality hazard rate past one year of age. This is not captured by Gompertz-Makeham. This is likely due to trade-offs between parental investment and the genetic diffusion of life-threatening developmental disorders. Basically, any recessive inheritable risk that kills an infant within the first year of life leaves the parents with enough resources to re-invest into another attempt at procreation.

The primary impact of all our health measures has been to push down the Poisson-Makeham constant hazard component, thereby revealing larger portions of the Gompertz component. I have detailed observations available from large scale administrative datasets to back all this up if you are interested. This also leads to sum nearly state of the art mathematics, looking at Feller Processes on Lie Groups.

I'm glad your past few posts have been more playful and even positive(?)! It's refreshing. We may be facing decline but perhaps there's a reasonable chance of a new culture that fuses the knowledge gains of industrial civilization with long-term stable worldviews of many indigenous cultures. I dream of simple, permaculture villages with humanure toilets and composting, as well as PVs and LEDs and telescopes and microcontrollers. We may run down our fossil stores but we can't destroy atoms at scale so metals will be with us until the sun destroys the earth – and charcoal can be used for lots of refining and other thermal processes. Although scarce metals may be near impossible to source due to our processes that chew up concentrated deposits and spread them across millions of landfills at ppm or ppb levels (mostly to be reclaimed by rising seas).

I suspect anthropologists will be studying the current birth dearth for some time – will be tricky to untangle all the causes from cultural to economic to environmental but let's hope we evolve to a level that leaves more breathing space for us and all our fellow critters.

One minor point about Africa – I think the 85% figure you cite is wildly off. This sentence fragment from your reference: "From 2016 to 2018, Africa imported about 85% of its food from outside the continent" could mean that Africa imported 85% of its food – all of it from outside the continent, or (somewhat less obviously) – that of the food that nations within Africa imported, 85% came from outside Africa. I suspect it means the latter. This document: https://www.fao.org/fsnforum/resources/reports-and-briefs/why-has-africa-become-net-food-importer mentions that food imports in money terms are about 5% of Africa's GDP or $17 per person in sub-Saharan Africa. This one indicates that in calorie terms it's about 20% – https://www.statista.com/statistics/1314076/imports-as-a-share-of-calorie-availability-by-world-region/ – but that would need to be offset by exports to get a better idea (and there have been big moves by international actors to grab land in Africa to produce food for export – e.g. https://www.theguardian.com/film/article/2024/jun/12/the-grab-documentary-review).

North Africa and the Middle East do seem to be in a much worse position – that statista has them at 65%. I really wonder how countries like Egypt with exploding populations and an overloaded resource base will manage. But even there fertility trends are downwards (still well above replacement, though).

Thanks for digging up other numbers. The 85% was shocking to me, and I should have done more searching. But, my argument does not hinge on 85%, insofar as Africa currently has 1.5 billion and imports food. How is a putative 4 billion to be provisioned? If food is grown on-continent, then it becomes a matter of major fossil fuel imports for fertilizer and industrial agriculture (amidst possible scarcity, and paid for how?). I could believe water to be another major concern. My sense is that biophysical realities will tend to tighten down, rather than open up.

I believe you have missed a salient point about the falling fertility rates. What is happening is not women having fewer children. More people are choosing, consciously or otherwise, to have no children. This can be seen as the ratio of the number of children in families has not changed very much, except there is a much higher number without any children.

This seems to be the case in all countries where the economy is driven by consumerism.

We should look at the start of this phenomenon in the sixties to find the reason for this. In the West two relevant things were happening at roughly the same time. Governments were moving away from a Full Employment economic model leading to greater youth unemployment, at the same time they were encouraging young people to move into tertiary education. This worked directly against that part of Human Nature which said that 'Young men need to acquire enough social capital to attract young women and persuade them to set up homes together.'

The optimal time for this is around 10-15 years after puberty after which the urge to pair bond diminishes in both sexes.

Quite interesting reflections.

Demography depends heavily on resources, but also on ideological factors. In the end, resources prevail, but ideological factors play a very important role in between. So while the TFR is decreasing worldwide, it is not everywhere, and it can change at any time if the prevailing worldviews change. The most notorious counterexample is the Israel-Palestine case[1], where demographic competition has been developing for decades. And I can't help but think that the current behavior of the state of Israel in Gaza is not unrelated to this competition.

[1] Its population pyramids are very revealing. (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Demographics_of_Israel) (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Demographics_of_the_State_of_Palestine)

I'm curious to hear more about how you see the differences between Africa and let's say South/Central America. Do you think Africa will start following a sharp drop like Mexico's soon, or it might take another few decades? It does seem unlikely to me that it'll follow a linear trend all the way through 2100 rather than sharply dropping at some point as all other countries have eventually transitioned.

But I did notice that in your previous article [https://dothemath.ucsd.edu/2024/06/whiff-after-whiff/] you only picked non-African countries which produces a somewhat misleading conclusion that the UN always underestimates TFR drops.

I don't know enough about the histories of South America vs. Africa to say, although I'm pretty sure that the European influence is much stronger in South America. Mexico has had a close relationship to the U.S. in trade, which has boosted industrialization in a way that is less likely to be associated with Africa. So I'm not sure we could expect Africa to mimic Latin America.

I didn't really do the "picking" in the "Whiff" post. I looked at the fastest-dropping from 2010 to 2019 (largest ratio of TFR), also requiring the presence of UN projections in 2010, 2012, 2015, 2017, 2019, 1nd 2022. So it was a complete set, and none of the high-TFR African countries satisfied the ratio criterion I set. Since what I was trying to answer is why the U.N is missing the rapid TFR decline in the "developed" world in their models, I feel justified. I was not setting out to understand Africa, in other words.