This is the ninth of 18 installments in the Metastatic Modernity video series (see launch announcement), putting the meta-crisis in perspective as a cancerous disease afflicting humanity and the greater community of life on Earth. This episode asks how we landed ourselves in this unfortunate meta-crisis. Nobody planned it, but here we are!

As is the custom for the series, I provide a stand-alone companion piece in written form (not a transcript) so that the key ideas may be absorbed by a different channel. The write-up that follows is arranged according to “chapters” in the video, navigable via links in the YouTube description field.

Introduction

This is the usual short naming of the series, of myself, and the topic of this episode (how we got into this mess) as part of our effort to put modernity into context.

Sudden Destruction

Modernity might be characterized as a period of rapid ecological destruction: a sort-of nosedive in a relative blink-of-an-eye, as discussed in Episodes 7 and 8. The situation looks pretty dire: a sixth mass extinction appears to be underway. The community of life on Earth is reeling, struggling to survive in the face of significant change and decline.

How did it come to this? I will offer a three-step process that led us down this track.

Step 1—Agriculture

The first significant step is the initiation of agriculture, about 10,000 years ago. Agriculture took us out of our ecological context. The practice was new to the planet—new to the community of life, which was not adapted to this novelty. We could classify it as an experiment that was not vetted by ecological communities on timescales that are relevant to evolution.

Agriculture upends nutrient cycles that have been established and tested over long periods by ecological communities. The practices of agriculture might artificially supplement soils with fertilizers, but not in a way that the system is adapted to handle. The miracle of life is in the ability of a local ecology to set itself up around available flows of materials in circulation within each region. Outside of flood plains, which refresh nutrients in a longstanding rhythm, it’s not clear that our meddling has a durable future. This is part of why arable land is used up and lost over time (e.g., the formerly fertile crescent): salinization, desertification, nutrient depletion. Bear in mind that even ten thousand years is very short in evolutionary/ecological terms.

Just as importantly, the adoption of agriculture also went to our heads. We came to consider ourselves as masters of the land, controlling nature. We asserted ourselves as owners of the land (property rights!)—as owners of the Earth, in fact. No longer believing we belonged to the planet, we thought it belonged to us. Religions sprang up to reinforce this thinking—elevating humans over all life on Earth. I can’t overemphasize how crucial this development was in changing how we view ourselves in relation to the community of life, and thus justifying our actions. This is when the divorce started: our separation from nature and an acquired air of human supremacy.

Step 2—Science & Technology

The Enlightenment brought us a lot of sharp new tools that we could use to pick the locks of nature’s secrets. Indeed, we learned tons about the inner workings of the universe.

What did we do with this new set of insights? We used it to increase our mastery, control, and manipulation of the natural world for short-term gains among humans alone (and not all humans, it should be noted).

The focus became increasingly narrow, and increasingly distant from ecological concerns as our world became more disconnected, decontextualized, reduced, abstracted, linearized, objectified, and increasingly virtual in character. The resultant world lacks basic ecological sense—a state of affairs that, like a raging party, is not possible to maintain beyond the short term.

In the meantime, we’re very impressed with our inventions. It turns out that brains are impressed by brains—flattering themselves as having unlimited potential, in blatant disregard of plain facts. I’m sure lots of people can rattle off their favorite impressive accomplishments of civilization. No one asks, for each one, what as been the net benefit to the entire community of life, on balance? How is the world beyond the isolated (thus temporary and artificial) human domain better as a result? Huh? Don’t expect people to even understand the question. As a consequence of this glaring oversight, the harms just pile up and will bite us in the butt when our Club membership is terminated by our destroying Club functionality.

Step 3—Fossil Fuels

Fossil fuels utterly transformed how we went about our business. They dramatically turbo-charged our ability to manipulate and control. We now had the means to carry out almost any fool notion that popped into anyone’s head.

It’s as if we gained super-powers. We could move mountains, divert rivers, hold back the sea, build submarines to dive deep, airplanes to fly high, and rockets to even reach space. We did not swim or fly as elegantly as life, but achieved a sort of awkward impressiveness in our kludgy ways. It seemed a sort of transcendence: breaking free of the limiting shackles of nature. Yet all of this, remember, is temporary—illusory.

The Green Revolution transformed agriculture by inserting fossil fuels at every turn. Fertilizer came from natural gas. Diesel allowed large-scale mechanization of plowing, planting, harvesting, processing, and transporting large amounts of food. Petrochemical pesticides smote economically-worthless (but ecologically-invaluable) products of evolution into the foul dust. We fed a growing human population, now 8 billion strong. It boils down to a diet of fossil fuels: again, temporary.

Hockey Stick Gallery

Increasingly heavy use of fossil fuels translated into a world characterized by “hockey stick” curves. A hockey stick is straight for a long time, then suddenly sweeps up. Almost any absolute measure one plots in the human sphere takes on this shape. Not only has human population followed a hockey-stick curve, but even per-capita measures have done the same thing so that the absolute scale of such things as energy, materials, and waste shot up as even more exaggerated hockey sticks. CO2—a necessary product of fossil fuel combustion—naturally shot up as well, and is the main reason many people know the term “hockey stick curve.”

In the presentation, I show a gallery of hockey stick curves that I won’t belabor here, as a post called Death by Hockey Sticks has already done that job. Suffice it to say that plots of human population, energy, CO2, copper (as a proxy for mined materials), and plastic disposal (as a proxy for waste) all rocket upward in heroic fashion. Where are they going? Back down, as they must. More on this later.

Ecological Hockey Sticks

I also show some ecological measures:

- Extinction rates for amphibians, mammals, and birds. Is it to be celebrated that these measures are also shooting up in hockey stick style?

- Forest cover, which is declining globally and projected to hit zero by 2200, if the current inverse hockey stick is maintained.

- Old-growth (primeval) forest cover, on track to zero-out by 2100

- Wild land mammal mass, plummeting toward zero frighteningly fast—the curve hitting zero by 2050!

Now, the projections (when the curves hit zero) are not to be taken literally. I mean, the mathematical curves as such keep going and become (impossibly) negative. On the other hand, PANIC! The trends can’t be spun to be fine, normal, or healthy in any way. The history has been tragic for the more-than-human world, who receive none of the benefits and the lion’s share of the cost. I show again the mammal mass per person, as featured in Episode 7 and in the Ecological Cliff Edge post. The rate of descent is truly alarming and clearly way out of whack.

What do these trends make you think about our trajectory, given the accompanying stark downsides? Are we applauding? Are we excited?

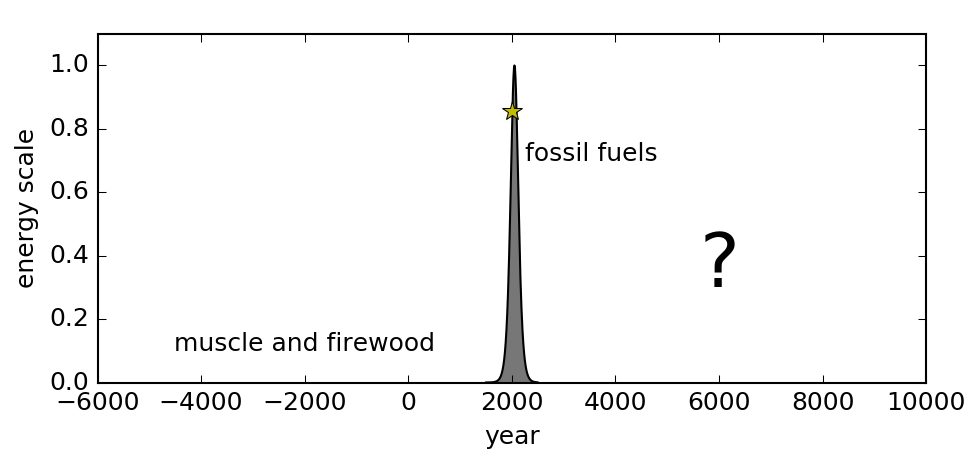

Fossil Fuel Spike

I show the following recurrent cartoon of fossil fuel use over time, which can’t be far from being accurate, given the nature of the beast.

It’s just a spike. The hockey sticks we’ve seen are directly tied to the left side of this feature, rocketing upward for a time. We haven’t crawled over the peak yet, but…wait for it…we will—and perhaps as soon as the 2030s.

I can say this with confidence, because the fossil fuel curve necessarily self-terminates. It must go back to zero. We don’t have the freedom to draw it any way we wish, because the area under the curve is set by the total resource amount, which pays no attention to anything our neurons decide they might wish it to do. I know from teaching students that this fact comes as a surprise to many, which says a lot about the narratives we use to condition our culture.

Our individual lives are short enough that we have each ridden up the ascending top portion of this curve, and therefore perceive the state of affairs for the handful of decades we’ve been around as normal (and fun, for some). Can you believe that? Wow! Whatever we use our brains for, it’s not for appreciating the broader context, by-and-large. In any case, the emerging narrative is both wrong and dangerous.

The River

Next, I pop up the graphic from a post called Our Time in the River. I don’t belabor it, but I mention a list of consequences of our stepping into the agricultural stream 10,000 years ago. The story mirrors the three steps outlined above.

Agriculture led to settlements, then possessions, surplus, armies to protect (and raid) surplus, property rights, patriarchy and monotheism, division of labor, hierarchy, classes, and subjugation of animals and humans. Many negative ecological impacts also accompanied agriculture such as deforestation, soil erosion, salt accumulation, desertification, among others.

Then, science joins the flow as a powerful tributary that serves to accelerate these patterns. Shortly after, fossil fuels flooded the river to super-charge our degree of control and speed. The river then goes over a waterfall, self-terminating as it must—given its erosion of the ecological riverbed.

How Should We Live?

All of this leaves us confused about how to live on this planet. We are now far removed from our ecological context and struggle to define the right way to live in this messed up, artificial, temporary, human-constructed “world.” The way we live now is unusual, exceedingly new, and never quite feels right. Note that animals (aside from domesticated ones, perhaps) are not at all confused about how to live in this world, when immersed in their ecological context (they can become confused about how to function in our artificial, novel context—frozen in the headlights, as it were).

No one planned this. One thing just led to another, as in the metaphor of the river with its tributaries. No one sat around a table and plotted this course. It operates more like a trap: once you start going, this is where you end up, given the resources at hand.

We’re executing a sort of “look what we can do” behavior, like kids trying to impress each other doing stupid stunts on bikes, as I frequently did as a kid. It’s part of testing our limits—learning what we are—and are not—capable of doing. It’s time for us to abandon this adolescent phase and start asking bigger-picture questions about the consequences of our actions. Right now, we are accumulating a lot of collateral damage on the ecological front—endangering the entire community including ourselves.

The core failure is in forgetting our ecological context. We are (for now) members of the Club of Life. We are not, at present, prioritizing long term sustainability or overall ecological fitness.

Closing and Do the Math

Next time I’ll address the question: can’t we just get rid of the bad stuff and keep all the things we like about modernity? If only.

I’m glad you found the companion write-up. You need no extra encouragement, it would seem.

Views: 3139

Thanks for this series! Very enlightening! People are quite gym-crazy now to improve their personal fitness. It's time to start attending the 'Gym of Life' for improving our ecological fitness. I wonder what that Gym of Life looks like…

"I wonder what that Gym of Life looks like…"

Endosomatic energy. Hauling manure. Digging soil. Nomadic herding.

I'm particularly interested in this last point. Traditionally, it's been up into the mountains in the summer, and down in the valleys for the winter. But with climate change, it may be north in the summer, south in the winter.

I agree that agriculture was the beginning of the end. But it may not be possible to return to hunting and gathering. We might have to do pastoralism. But that will have to wait for the end of property rights.

Another excellent summary. Like all species, humans expand into every habitat and dissipate any energy gradient. Energy surplus means life. But unlike other species, we have removed most of the short-term negative feedbacks on population control. Hence, we have population and consumptive overshoot. Bill Rees has talked about this a lot. Our ecological footprint – the per-capita area for all materials we need and for assimilation of all wastes — has been greater than one planet since the 1970’s. Yes, its very uneven depending on wealth. Changing the path does not depend on magical future technology or money, it depends on whether we (rich people) want a World where we use less energy and have less material stuff. Such a World sounds good to me if we can share it with Nature.

Leaf-cutter ants are farmers and have been, I guess, for millions of years. Humans have also occasionally managed at least somewhat sustainable farming and horticulture. I'm thinking of native American forest gardens, Chinese paddies… Us moderns are experimenting with agroecology and permaculture, regenerative agriculture.

So I think it can be done, provided there's not so many of us. The tricky part will be retaining the useful bits of civilisation while reducing our population and replacing Capitalism with something that works.

I agree that agriculture is not necessarily a planet killer. Muscle powered agriculture can produce a small civilization that can screw up a local region, but the rate of ecological destruction can't overwhelm the healing powers of nature. That is, unless something like fossil fuels magnifies the process by several orders of magnitude.

Agriculture has been a common occurrence all through the Holocene, but imagine what the world was like in the pre-fossil-fuel era (say about 1600), even with agriculture going on. CO2 ppm of about 280, perhaps just enough to head off another ice age. World population under 500 million, 60% of which was in India and China, leaving the rest of the world with plenty of wilderness. Marine life barely touched. Wildlife almost everywhere. Wouldn't we love to be in that situation now!

The fossil fuel spike was the dagger in the heart of nature. Without it, no mass extinction and no climate change. Too late now.

There are definitely some steps that seem to be more consequential than others, as you've pointed out. However, the human journey has been a continuum. As you've also pointed out, one thing led to another. But this applies to the whole journey. If only our predecessors hadn't invented the digging stick, we'd be much more like other species, or our species might not be here at all. Unfortunately, we can't change the past and have no free will to alter our path into the future.

Agree that the past is done, and essentially *had* to go that way. The future is unpredictable, even if deterministic. It depends on the complex set of stimulus/response reactions that develop according to the circumstances. Humans absolutely can change the course of the future, through our actions, even without free will. It's a question of whether it unfolds that way or not. I appear to be an actor calling attention to the stimulus that might produce a reaction more favorable in the long term. It's a long shot.

After-note: Several comments opened debate on the free will topic, which is a rehash of prior Do the Math threads on that topic. Since it's not the point of this series, I'm terminating the tangent before it grows any more. Sorry for contributing/echoing the point, but will leave it there.

The problem (as many, including yourself, have said) is we're born into, and live our short lives entirely within, the system, so that it feels normal (to most).

'Leaders' and politicians epitomise short-term thinking. They will never change, because they live well off the exploitation system (and always have).

So it seems to me that the system will continue until it can't – ie nothing will change its direction until it hits the buffers.

After that, 'leaders' won't be able to acquire the same power again.

Only then will humanity abandon its adolescent phase.

Thanks again for your blogg, Tom. I learn new things every time I read it.

The other day I listened to a program about nature and biodiversity in the Swedish public service radio. They talked about how grass occured quite a long time ago and when big herbivorous animals appeared and how they made it possible for new kinds of plants which were favoured by light to develop enriching the biodiversity. As the ice smelted, humans came along northwards hunting and also bringing agriculture to all of Eurpoe some 7000 years ago. In the radioprogam it was said that it was lucky for the biodiversity that agriculture came just as some of the big herbivorous animals became extinct. Humans took by introducing agriculture with cattle responsibility for the biodiversity by becoming the gardeners of the nature.

Well, I find this description being somewhat backwards. I am not a scholar but I wonder if spreading agriculture isn’t rather an early example of when humans caused loss of biodiversity e. g. aurochs getting extinct to give space for their cattle. Is this an early step towards what has happened since with the flora and fauna? The growth rate was initially very low for several thousand years but has steadily increased until the Earth by now has got enough. The extinction of species has gone faster and faster causing the biodiversity to get smaller and smaller. No cattle in the world can restore the biodiversity. Biodiversity developed, as far as I understand, without help of domestic animals.

I would very much appreciate comments on my thoughts. Please correct me, if I am wrong.

I'm in no position to offer proof of the real story, but the one you describe from the radio program strikes me as a revisionist rationalization that has it backwards—in service of promoting humans as the saviors (a common tendency). Meanwhile, megafauna extinctions followed humans around the globe as we migrated into new places. Seems far more than coincidence, and fairly conclusive—especially as we tend to hunt large animals. Indeed, it is hard to imagine the displacement caused by domestic animals promoting *greater* biodiversity, when the opposite is a more obvious result—quite visible by now.

"Disaster" seems somehow to be an understatement for where we're heading. 8+ billion people all dependent of the the burning of fossil fuels for their existence, while that burning is creating an unlivable climate. What would an outside observer recommend as the best course of action at this stage ? Probably cease the burning of fossil fuels while there is still a chance of preventing further destruction of the biosphere and retaining a livable climate over most of the planet, accept the inevitable die-off of that would inevitably follow, and for the survivors to not use fossil fuels at all. That won't happen ,of course, but the die-off is inevitable later this century, and the unceasing burning of fossil fuels to maintain and construct further infrastructure, and the continuing destruction of the biosphere will by then have left any survivors with a far more inhospitable and depleted environment . We've created this nightmare, and no celestial being is coming to our rescue. All our own work,doing whatever seemed like a good idea at the time.

Ignorance is a mighty impediment, David. In my local cafe earlier this morning, a discussion on pollution was well underway when I arrived, prompted by another sewage discharge into the sea, which has closed our beach once again. This developed to vehicle emissions, whereupon a local councillor proclaimed atmospheric pollution was a fallacy. He thinks all the “bad stuff” is ejected from the atmosphere into outer space and the entire ecological crisis is manufactured by “politicians who want to curtail our freedoms”. Sadly, most of the audience seemed to agree.

Yes, no shortage of that at all. We (Australian ) had a prime minister (Tony Abbott ) who won an election largely on encouraging the belief that climate disruption was a hoax .

( I don't remember him actually using the word hoax, but that summarises the Trumpian essence of it ). One of his declarations was that an invisible and weightless gas (CO2 ) could not possibly have harmful effects.