Although I might be described as a dyed-in-the-wool scientist, I’m about to say some things that are critical of science, which may be upsetting to some. It’s like those warnings on a movie or show: strong language, nudity, smoking, badmouthing science. So, before I lay into it, let me express some appreciation for what science does remarkably well.

- Science exemplifies careful observation—isolating confounding factors to focus on a particular interaction.

- Science follows a method that suppresses personal attachment to an idea: nature becomes the arbiter of truth.

- When it comes to elementary particles and fundamental physics, one can hardly do any better; although even an atomic nucleus is complex enough to defy exact treatment.

- Science advances by trying to tear itself apart, so that surviving notions are very strong.

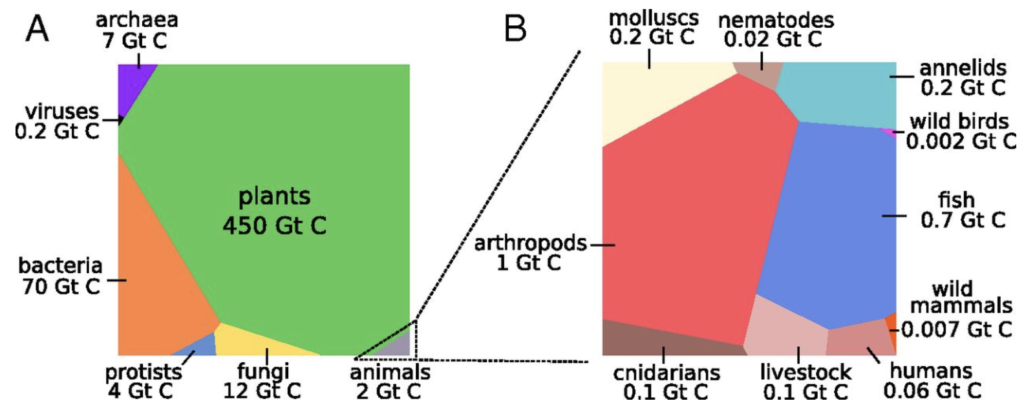

- Because of science, we have a decent outline of how cosmology, evolution, and biophysical systems work.

It has its place.

But the very thing that makes science powerful is also its biggest weakness. It relentlessly pushes wrinkles aside, smoothing its zone of interest to the least complex system one can obtain for study. This is ideal when wanting to observe a Bose-Einstein condensate in isolation, or the genetic mechanism for producing a certain protein. Science also tends to dissect a problem (or literal critter) into the smallest, disembodied pieces—which then have trouble relating back to the whole integration of relationships between pieces. Other “ways of knowing” attempt to grapple with the whole, accepting it as it is and not applying reductionist tools.

Views: 4767