A while back I wrote a post pointing out a way to see that animals are worth more than their weight in gold. The concept was cute, but not fully defensible in detail. Yet, the many orders-of-magnitude difference in market value of animals vs. their gold-equivalent value at least indicated that we might have something wrong, on the basis that we can’t live without the animals, but could live without gold.

In this post, I will follow a similar path to arrive at what I think is even a more stark result: that the economic value of arthropods (e.g., insects) is something like $10,000 per kilogram. To get here, we need to first preview the numbers.

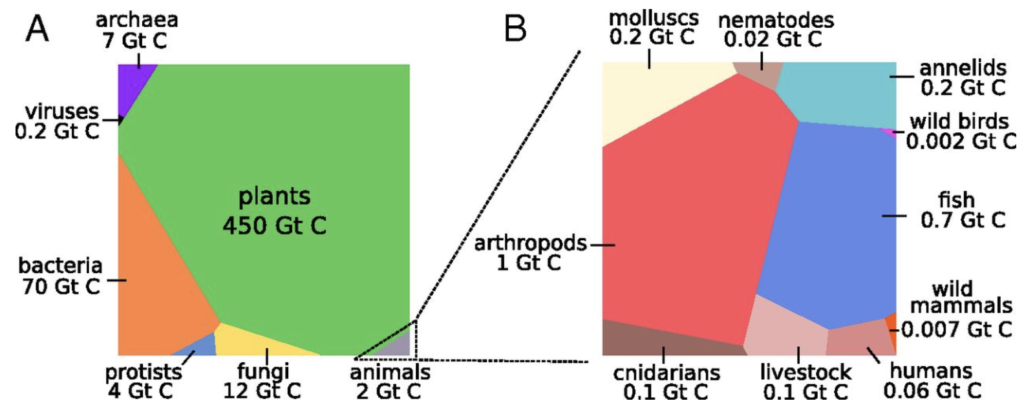

A look at Figure 1 in a 2018 paper by Bar-On at al. (reproduced above) shows that Planet Earth hosts 2.4 Gt (giga-tons) of animals, in terms of dry carbon mass. The largest block within the animal kingdom is arthropods (includes insects, spiders, centipedes, and crustaceans), at 1 Gt. Fish are nearly as big, at 0.7 Gt. By contrast, wild mammals are only 0.007 Gt, and wild birds are a comparatively tiny 0.002 Gt.

I have pointed out before that humans now vastly outweigh wild mammals, to the point that we only have 2.5 kg of wild land mammal mass left per human on the planet (presently plummeting). Note that this is a “wet” mass figure, whereas the numbers above are dry carbon mass (about 15% of wet mass).

The trends are falling fast: insect, bird, mammal, amphibian, and fish populations are losing ground to the tune of 1–2% per year, amounting to halving populations over a handful of decades [late addition: good article on subject]. Inevitably, then, extinctions are up a thousand-fold, and increasing. This is decidedly not good, and perhaps the most glaring sign that modernity is a literal dead-end path.

The approach here is to assume that Earth’s ecology would crash without any arthropods. The same might be said for fish, or birds, or any major group. Bugs (an informal catch-all substitute for arthropods here) are particularly attractive to me for this exercise because they are so crucial in terms of food for others, soil conditioning, pollination—and other services—that it is hard to believe other phyla could carry on without them. Evolution produces a complex interconnected web that cannot be expected to maintain its overall integrity if surgically plucked apart in this way—much as an organism cannot be expected to survive if completely removing any one of many key organs.

Therefore, no bugs, no humans. No them, no us. The same argument could probably be made for other phyla, producing slightly different quantitative results than what follows, but the same in spirit.

Views: 2413