One consequence of having developed a perspective on the long-term fate of modernity is a major disconnect when communicating with others. Even among people who have a sense for our predicament, my views often come across as “out there.”

Let me first say that I don’t enjoy it. Having different views than those around me makes me uncomfortable. I was never one to make a point of standing out or of having a contrary opinion for the sport of it (we all know those people). My favorite teams as a kid were the local ones (Falcons, Braves, Mocs), like everyone else around me. I wear blue jeans basically every day, blending in to Americana. No tattoos, piercings, or “non-conformist” affectations. It is, in fact, because of my continual discomfort at having stumbled onto a divergent view that I am compelled to write and write and write about it. I feel trapped between what analysis suggests and what almost everyone else around me thinks/assumes. The discomfort means that I keep trying to discover where I’m wrong (my life would be easier!), but the exercise usually just acts to reinforce the unpopular view.

In this post, I want to try to turn the tables: make members of the mainstream feel uncomfortable for a change. It probably won’t work, but I’ll try all the same. I could have titled the post: “No, You’re Crazy.”

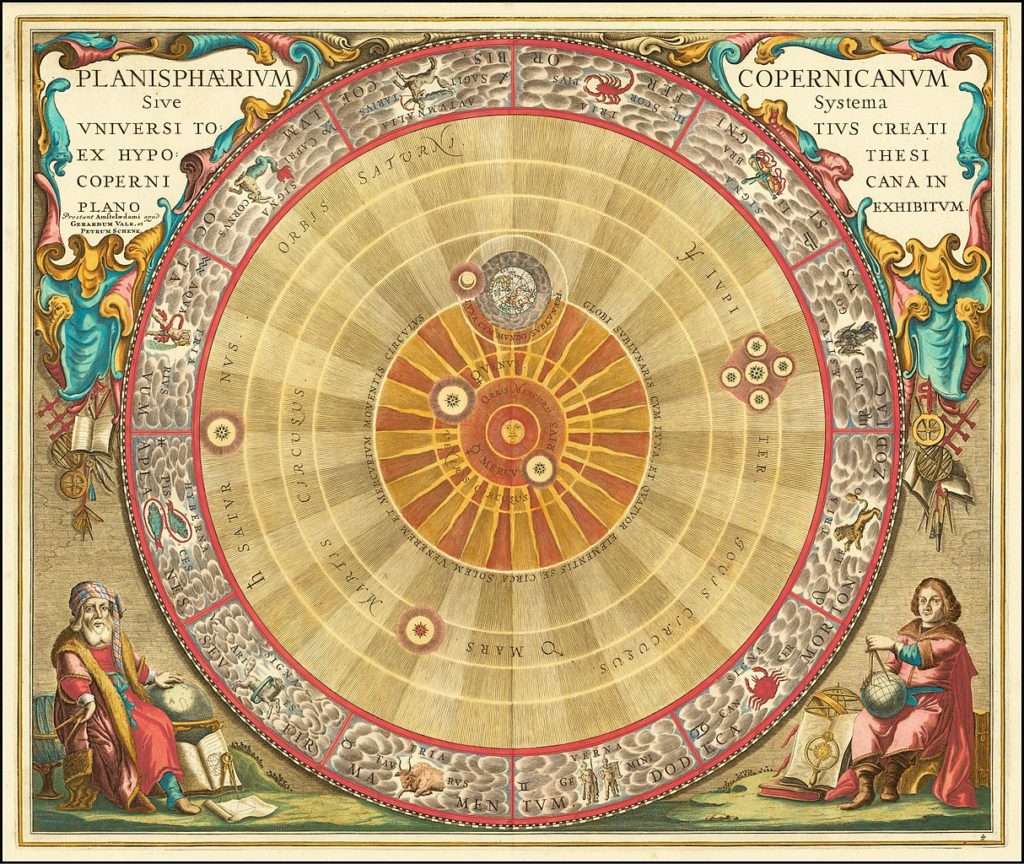

My mental image for this post is one of a fishbowl in a vast and varied space devoid of other fishbowls. The fish living in the bowl have each other, the enveloping water, a gravel floor, fake plants, a decorative castle, and manna from heaven morning and night. Concerns of the fish need not, and in a way cannot extend beyond the boundaries of the bowl. The awkwardness is that the bowl is wildly different than the rest of the space in all directions. It’s the anomaly that the inhabitants deem to be normal. The analogy to ourselves in modernity should be clear…

What happens when the caretaker of the fishbowl disappears: when the food stops coming, and the environment becomes fouled? The artificial context of the bowl ceases to function or even make sense. The best outcome for the fish might be to get back to a pond or stream where they could live within their original context: woven into the web of life, enjoying and contributing to a rich set of “ecosystem services.” But getting there is not easy. Once there, figuring out how to live outside of the dumbed-down artificial construct presents another major challenge. As good as the fish seemed to have it, the fishbowl turns out to have been an unfortunate place to live. I invite you now to re-read this paragraph, substituting modernity for the fishbowl.

Views: 3237