When I proposed ten tenets of a new “religion” around life a few months back, the first tenet on the list said:

The universe is not here for us, or because of us, or designed to lead to us. We are simply here because we can be. It would not be possible for us to find ourselves in a universe in which the rules did not permit our existence.

While simply stated—perhaps to the point of being obvious—it is shorthand for a fundamental principle that has become a wedge issue among professionals who seek to understand the nature of the universe we live in, and the rules by which it operates. In this post, I will elaborate on the meaning and the controversy behind this deceptively simple statement.

The Schism

As a form of entertainment accompanying my journey through astrophysics, I witnessed a schism develop at the deepest roots of physics and cosmology. In brief, many physicists pursue a common quest to elucidate the one logically self-consistent set of rules by which the universe works: a Theory of Everything (ToE), so to speak. In other words, every mystery such as why the electron has the mass that it does, why the fundamental forces have the behaviors and relative strengths they do, why we have three generations of quarks and of leptons, etc. would all make sense someday as the only way the universe could have been.

An opposing camp allows that some of these properties may be essentially random and forever defy full understanding. Those in the ToE camp see this attitude as defeatist and point out that holding such a belief might have prevented discovery of the underlying (quantum) order in atomic energy levels, the unification of electricity and magnetism, reduction of a veritable zoo of particles into a small set of quarks, or any number of other discoveries in physics. Having self-identified in the “defeatist” camp, I knew for sure that the purists were just plain wrong about my position stifling curiosity to learn what we could. Our end goals were just different. I was content to describe the amazing universe—figuring out how rather than why it worked—and didn’t need to find a “god” substitute in an ultimate Theory of Everything (a big ToE).

The counter-cultural viewpoint I hold sometimes goes by the name The Anthropic Principle, simply because it acknowledges the fact that we humans are here—so that whatever form physics takes, it is constrained by this simple and incontrovertible observation to produce conditions supporting life. It amounts to a selection effect that would be insane to pretend isn’t manifestly true.

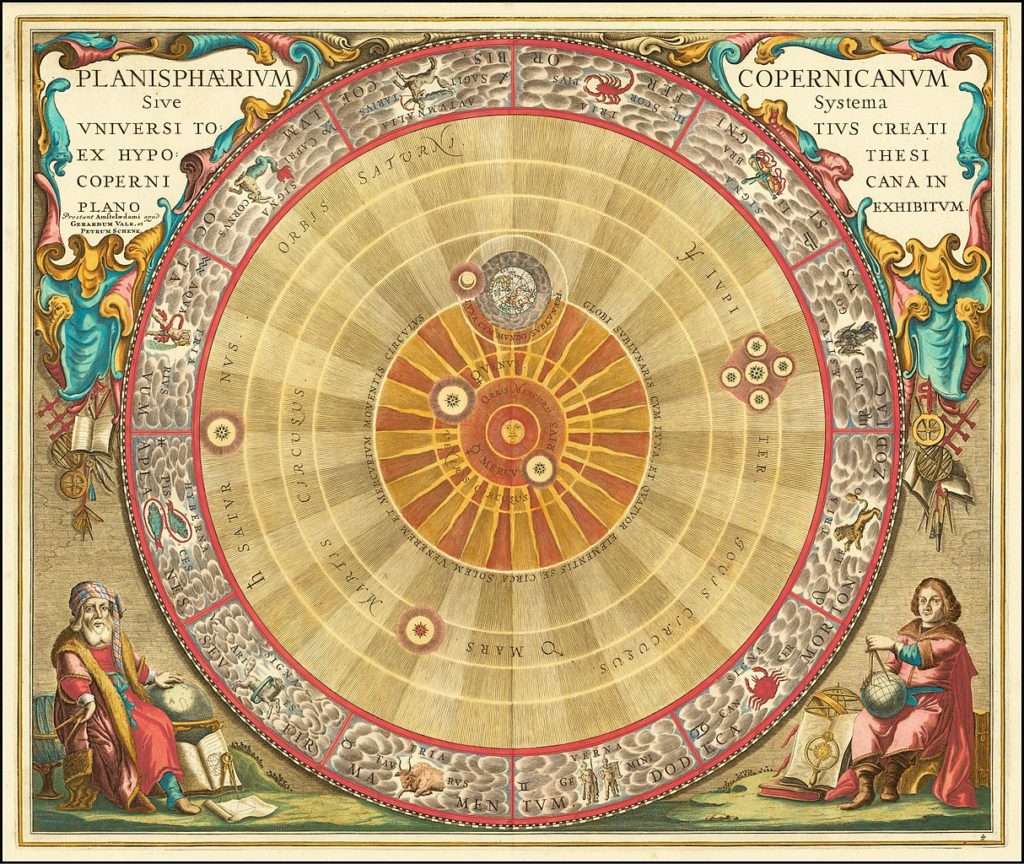

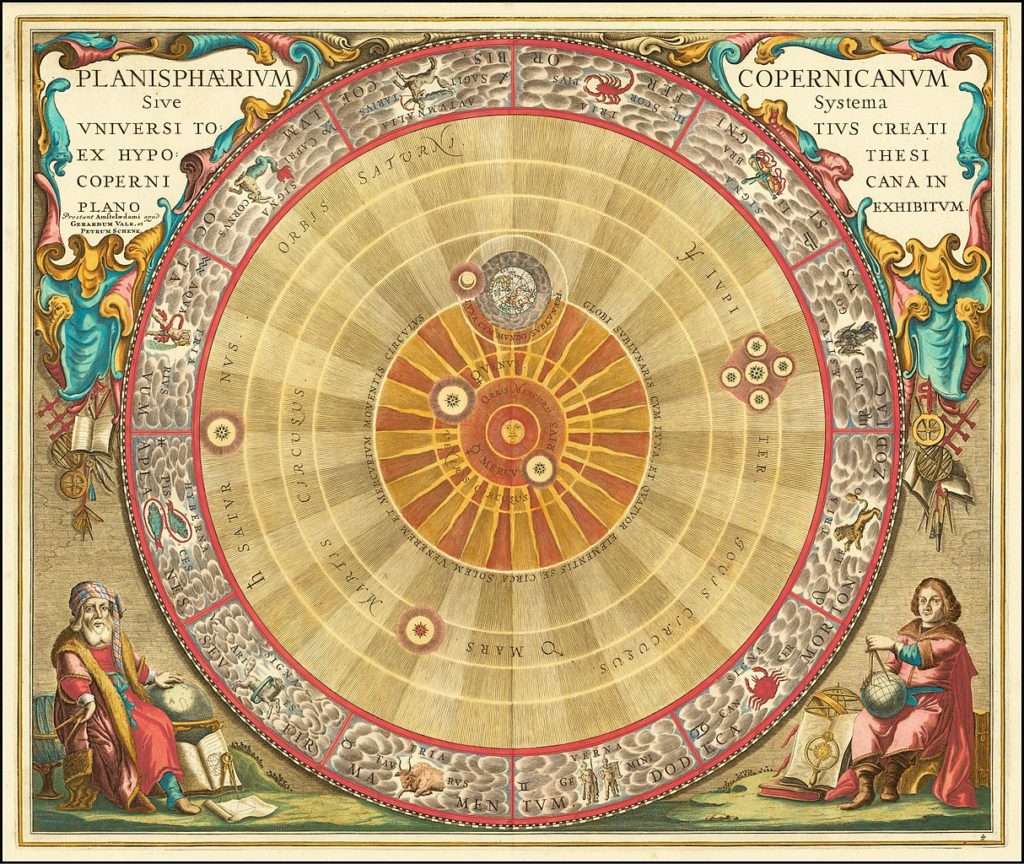

Scientists are perhaps too well trained to remove humans from the “equation,” and I can definitely get behind the spirit of this practice. After all, the history of science has involved one demotion after another for human importance: Earth is not the center of creation; the sun is not the center of the universe (the universe doesn’t even have a center)—or even the center of our galaxy; moreover, our galaxy is not special among the many billions. Ironically, even through the Anthropic moniker seems to attribute special importance to humans, the core idea is actually the opposite, translating to the ultimate cosmological demotion: our universe isn’t even special: a random instance among myriad possibilities. Yet, I suspect the name itself is a barrier for many scientists, as it seems superficially to describe an idea built around humans—which is a non-starter for many.

I can definitely sympathize with this reaction, as an avowed hater of human supremacy—a sworn enemy of the Human Reich. Don’t get me wrong: I’m not a misanthrope. I love humans, just not all at once on a destructive, self-aggrandizing rampage. Yet for all my loathing of anthropocentrism, I am fond of the Anthropic Principle. What gives?

Basically, I have to ignore the unfortunate label. A rose by any other name is still a rose. I propose using a less problematic name that gets to the same fundamental point: The Biodiversity Principle. I’ll explain what the principle is (by any name), and eventually how it relates to modernity and the meta-crisis as a compatible foundation for long-term sustainability.

Continue reading →

Views: 4095