Several sources recently made me aware of a Techno-Optimist Manifesto clumsily assembled on social media by one of the world’s many billionaire nobodies. I didn’t get far before dismissing it as a delusional toddler tantrum. This impression was later reinforced via references to 50 billion people, space colonization, and thousand-fold increases in terrestrial energy. The part I did see told me almost all I needed to know, in the line: “We are told to denounce our birthright—our intelligence, our control over nature, our ability to build a better world.”

Birthright? Hmmm. Calls to mind blood and soil. It’s all there: destiny, rights, self-flattery, obsession with control, and the hubris that we build the world—and can do it better, in fact. This is textbook human supremacy, which I believe is what got us into this mess! Doubling down will only make the loss more severe and catastrophic, in my view.

I have pointed before to the excellent essay by Eileen Crist on the topic of—call it what you like—anthropocentrism, human exceptionalism, or human supremacy. Part of the essay walks us through a disconcerting thought experiment about techno-social success of the sort that many today preach and seek:

…assume for the sake of argument that social justice is achievable on a planet of resources—a planet used, managed, and engineered to be productive for human beings. Let’s posit, along these lines, that humanity recognizes the folly of the unequal distribution of resources and decides to share the so-called commonwealth […] fairly among all people. This thought experiment discloses the second reason that social justice is untenable without a radically new relationship between humanity and the more-than-human-world. Consider the following analogy: that Adolf Hitler had won the war and the Third Reich achieved global rule. People of Nordic descent established their dominion, while “inferior human stock” was exterminated, assimilated, or put to work; the Aryan race succeeded in founding its Golden Age, with its members enjoying, more or less equitably, all the amenities of the good life. Now map this thought experiment onto the achievement of a just world for all humans (regardless of race, ethnicity, class, caste, religion, gender, etc.), within a civilization built upon the subordination of the Earth’s nonhumans and the appropriation of their oecumene (a.k.a. the wild)—a human world that, in order “to raise all ships,” required the unavoidable side effects of (mass?) extinction, global ecological depredation, and techno-managerial planetary oversight; required, in a word, an occupied planet. Does this scenario not describe a victorious Human Reich—with all its members partaking equitably of the world’s resources?

Compelling. The brilliance is putting ideals that seem to be on opposite extremes—equity for all (humans) and its vile antithesis of Nazi racism—in the same basket as both being comparably exploitative of an underclass. The feeling of whiplash is similar to what one experiences when recognizing that the most extreme on the political left share some common ground with the most extreme on the political right on an issue like drug legalization.

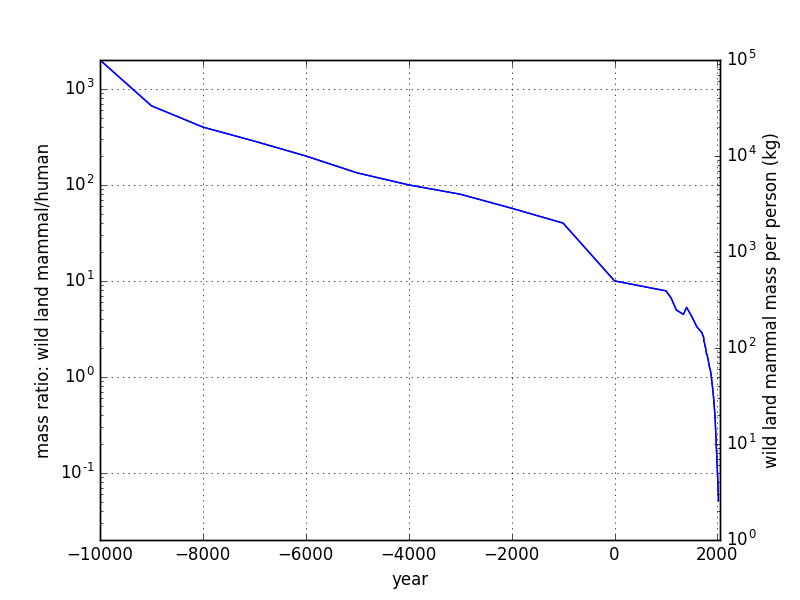

It’s unfortunate that we need to reference the worst atrocities against humans in order for the larger-scale atrocities against life to even register as a thing. Extinction rates are up a thousand-fold, and huge fractions of life are disappearing under human domination, but collective outrage only seems to emerge when one human group embarks on elimination of a sub-group of other humans, regardless of the relative magnitude.

What I thought I might try is to express the underlying beliefs of techno-optimists (those stalwart heroes of modernity) in language that I perceive would get general nods from most members of our society. In what follows, I have thought carefully about each sentence, and will point out later why every one of them is wrong—and I’m not talking about spelling or grammar (at least I hope those are okay).

It might be fascinating to pass the next section (four paragraphs) to others in your circles and see if it raises objections. To facilitate that, here is a link to a separate page that contains the same text in isolation, with minimal context. I would want every sentence to raise objections. But I’m guessing that most statements will go down easy, swallowed as familiar and correct mythology.

Views: 6286