It’s Tuesday morning and I didn’t prepare a new post, having been busy helping birds and bats. Maybe, though, the holidays have given you more free time than usual, so that you can afford to take in a podcast episode or two. If so, this post introduces two conversations I’ve had that do a decent job of capturing my recent perspectives. Below, I provide links and overviews of the content of each, in the form of the questions I was asked. Do you already know how I’ll answer each one?

Human Nature Odyssey: Astrophysics for a New Stone Age

About a year ago, I recommended a fantastic podcast called Human Nature Odyssey, by Alex Leff. If you haven’t listened to it, the previous link allows you to get up to speed on past episodes. Alex reluctantly read an assigned book at age 14 that changed his life, as the book has a tendency to do. That book is Ishmael, by Daniel Quinn, which I have touted in a number of posts. It was a key part of the Reading Journey I laid out a while back, further expounded in a dedicated post, and formed a large part of the inspiration behind my proposed Religion of Life.

Alex and I have had a few exchanges over the last year, and he honored me with a spot in his season 2 lineup of Human Nature Odyssey, titled Astrophysics for a New Stone Age. Alex edited the conversation into a tight dialog, adding his customary soundscapes to create a podcast having a higher-than-normal production quality. Paraphrasing Alex’s questions, here is how the flow went:

- What initially drew you to astrophysics?

- Why do you call yourself a “recovering” astrophysicist?

- How do you view science, now from the outside?

- What inspired you to start Do the Math?

- Wait: we’re not going to colonize space?

- How can you say that your “space laser” is far less impressive than a simple amoeba?

- How were you influenced by Daniel Quinn’s writings?

- Could you describe your cancer diagnosis for modernity?

- Why use the vague term “modernity?”

- The modernity cancer has perks: can’t we keep those?

- Are you suggesting that we go back to the Stone Age?

- Do you still lament losing astrophysics if modernity collapses?

- Are you using a map and compass on your journey?

- What aspects of science are valuable in a post-modernity world?

I like the conversation that emerged, and hope you do as well. It should be available through most podcast apps, including this Apple link, and also via YouTube (audio only).

Marriage Proposal (Teaser)

The second conversation was with Josh Kearns on Doomer Optimism (episode 246). And, yes, a marriage proposal pops up. This is a longer conversation than the previous one, happening to cover some similar ground (astrophysics, lunar ranging). But it also delves into religion, which I’m not sure I’ve discussed in other podcasts. It then touches on the fertility decline story and demographic modeling. Near the end, I think Josh implies that I’m fat, or will soon become so. Here is a paraphrased list of questions Josh put to me:

- What does it mean to be a recovering astrophysicist?

- How could you do lunar ranging if the landings were faked?

- What’s at stake in the potential collapse of modernity?

- What’s it like to shed the mythology of progress, and does that make you an outsider now?

- You define modernity as starting with agriculture: is that going too far?

- Could you summarize the Metastatic Modernity arc and messages?

- What’s your plan? Can this be a curriculum? Who’s your audience? Youth salvation?

- Are we preparing today’s students for yesterday’s world?

- What are your triage priorities: institutional or individual?

- Can you explain what human supremacy is and why you focus on it?

- What is your religious background and journey?

- You seem to have arrived at a new religion of sorts: can you describe this?

- Are there inroads to transform religions by carrying forward their best parts?

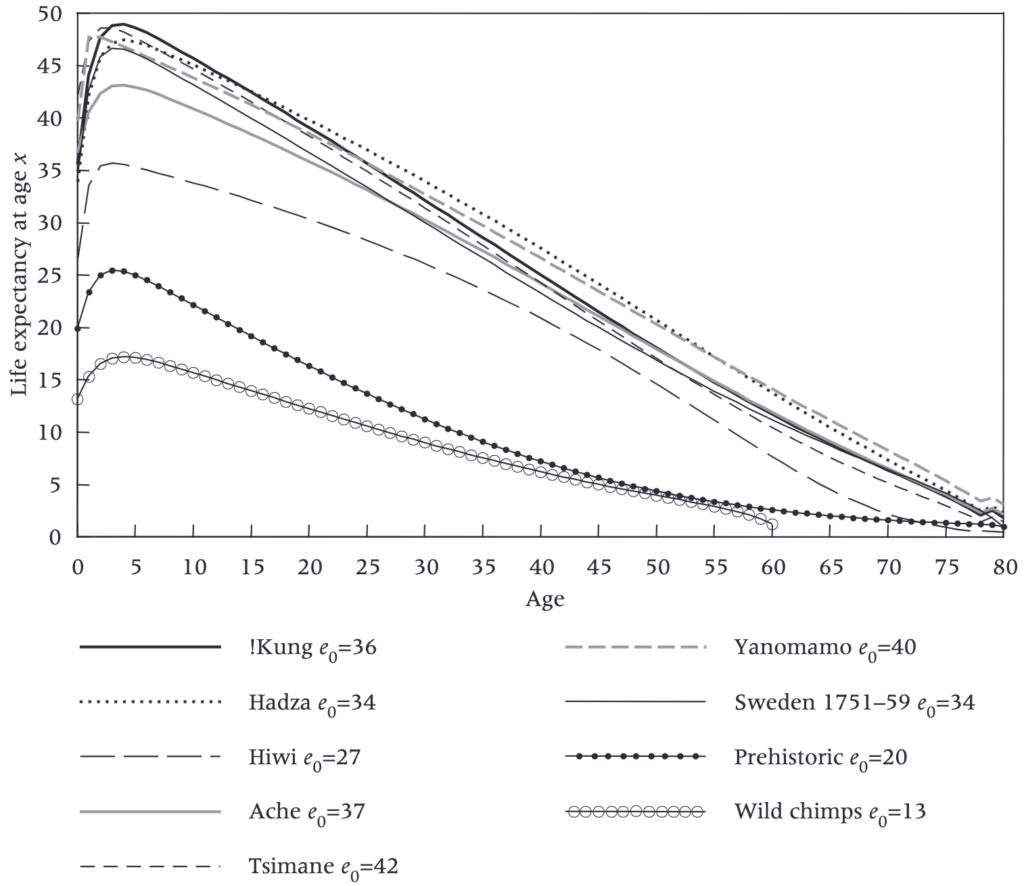

- Big shift: why is fertility rate falling rapidly and globally?

- How many completely wrong predictions can experts make before they give up?

- How can global energy use peak before global population peaks?

- What is the economic impact of declining energy use?

- If facing near-term demand-driven decline, should we start prepping now?

- Is there anything people fret over that they really don’t need to worry about?

As it happens, I speak slowly enough that playback at 1.5x speed is well-tolerated.

Tangelic Talks

About a month after this post went live, Episode 3 of a new series came out, so I’m appending it here. Here is the page for the episode. Note that a short article accompanies the piece, and additional questions and responses that didn’t make the edited conversation appear in textual form lower on the page. It was AI-generated, so might have some errors. The hosts were somewhat new to my line of thinking, so that this episode might be appropriate for others who haven’t been exposed to such reflections before. For regular consumers of my content, it’s going to be pretty familiar material. The direct YouTube link is embedded below.

Resistance Radio

Also out after this initial posting (February 16, 2025) is a second conversation between myself and Derrick Jensen (the first is linked from this earlier post, which covered modernity and the demographic fertility decline). You can find the conversation at Resistance Radio, or using this link to the episode. The conversation explores growth and its limits, as well as the impossibility of even holding steady at current levels. We also talk about why the obvious is obscure to mainstream culture, and what I would do if I were an energy czar. Derrick asks his guests to suggest sounds from nature for the intro and outro. For the first, I picked a chestnut-backed chickadee (whose chipper sounds make me want to laugh with them). For this, it’s a Douglas squirrel. I wish newts made noises I could use.

Crazy Town

[Added 2025.03.27] My friends from the Post Carbon Institute, Asher Miller, Rob Dietz, and Jason Bradford had me on their Crazy Town podcast recently. I enjoy each individually, and as a group: our conversations are always productive (and laced with humor). In this episode, after offering some laments over lost fragments of modernity, the guys have me define modernity, sketch my path from a technologist/scientist to a modernity critic, touch on why it can’t go on, and offer suggestions for falling out of love with it—while finding supportive community. It almost seems like cheating to do a podcast with such friends.

Views: 2013