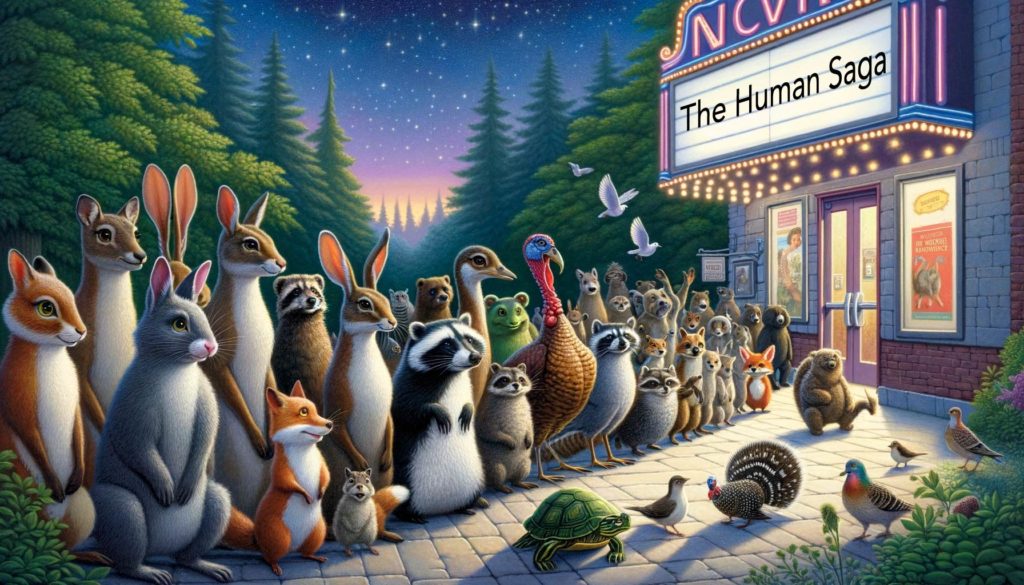

By accident, my wife and I stumbled onto the convention of calling essentially every living being a genius. It started as a joke about our cat, because obviously—in our human-supremacist culture—superlative traits like genius can only be applied to humans! Soon enough, this practice migrated to squirrels, newts, baby birds, ants—and even plants, fungi, and microbes. I no longer think of it as a joke.

I’ve utilized this framing in other posts by noting that every one of these beings knows how to do things we haven’t the foggiest clue how to do ourselves—or how, in detail, they manage it. I’ll get to the nuanced nature of the word “know” in a bit. But for now we can at least admit that the world is overflowing with phenomena we haven’t even registered, let alone understood. Typically, we just scratch the surface at best.

What I’ll do here is explore the relative genius of Life as compared to the normal use of the term, in the way of cognitive prowess. Let the games begin!

Continue readingViews: 3556